Dark Avenues (or Dark Alleys, Russian: Тёмные аллеи, romanized: Tyomnyie alleyi) is a collection of short stories by Nobel Prize-winning Russian author Ivan Bunin. Written in 1937–1944, mostly in Grasse, France, the first eleven stories were published in New York City, United States, in 1943. The book's full version (27 stories added to the first 11) came out in 1946 in Paris. Dark Alleys, "the only book in the history of Russian literature devoted entirely to the concept of love," is regarded in Russia as Bunin's masterpiece.[1] These stories are characterised by dark, erotic liaisons and love affairs that are, according to James B. Woodward, marked by a contradiction that emerges from the interaction of a love that is enamoured in sensory experiences and physicality, with a love that is a supreme, if ephemeral, "dissolution of the self."[2]

History

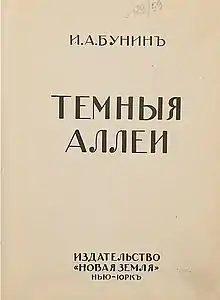

In 1942, when most of the European Russian emigres were hastily preparing to flee for America, Bunin with his wife, Vera Muromtseva, destitute as they were, decided to stay in France. Journalist Andrey Sedykh visited Bunin just before departing to the USA. As he was ready to leave the house, the writer said to him: "Last year I wrote Dark Alleys, a book about love. There it is, on the table. What am I to do with it here? Take it with you to America; who knows, may be you'll manage to publish it."[3][4] In 1943 600 copies of the book were printed by a small New York publishing company Novaya Zemlya (New Land).[5] Out of twenty stories Sedykh took with him only 11 were included: "Dark Alleys", "Caucasus", "The Ballad", "The Wall", "Muse", "Late Hour", "Rusia", "Tanya", "In Paris", "Natalie" and "April" (the last one later got excluded by the author from the second edition).[6]

Dark Alleys' full version (38 short stories) came out in 1946 in Paris, 2,000 copies printed. On June 19, 1945, the book was premiered at a public recital show in Paris which (according to Soviet Patriot, an immigrant newspaper based in Paris) was highly successful.[7] But the general response to the book was indifferent, according to Georgy Adamovich. "[The French] press reviews were mostly positive, occasionally even ecstatic, for how could it be otherwise, but unofficial, 'spoken' opinions were different and it caused Bunin lots of grief," the critic remembered.[8][9] It was translated into English by Richard Hare and published in London by John Lehmann as Dark Avenues and Other Stories in 1949.

According to Vera Muromtseva-Bunina her husband considered Dark Alleys one of his "moments of perfection".[10][11] Yet, Bunin continued to work on it and was making amends for each new edition.

List of Dark Avenues short stories

Only the titles of the 1946 edition are here included. One World Classics' deluxe edition (2008) features two more: "Miss Clara" and "Iron Coat".[12]

Volume 1

- Dark Avenues (or Dark Alleys, Тёмные аллеи). New York, 1943. The short story (and the collection) took its title from two lines of a poem by Nikolai Ogaryov's poem "An Ordinary Story" (Обыкновенная повесть): "Nearby the scarlet dog rose was blooming; / There was an alley of dark lime trees." Bunin himself reportedly preferred an alternative title drawn from the same poem: Dog Rose (Шиповник).[13]

- Caucasus (Кавказ). Posledniye Novosti, No.6077, Paris, 1937, November 14.

- A Ballad (Баллада). Posledniye Novosti, No. 6175, February 20, 1938. Paris. Bunin regarded this story one of his best ever. "Yet, like many of my stories of the time, I had to write it just for money. Once in Paris... having discovered my purse was empty, I decided to write something for the Latest News (Последние новости). I started remembering Russia, this house of ours which I visited regularly in all times of year... And in my mind's eye I saw the winter evening, on the eve of some kind of holiday, and... wandering Mashenka, this piece's main treasure with her beautiful nightly vigils and her wondrous language," Bunin wrote in The Origins of My Stories.[14]

- Styopa (Стёпа). Posledniye Novosti, No.6419, October 23, 1938, Paris. Written at Villa Beausoleil. "I just imagined myself at the riding britzka coming from brother Yevgeny's estate which was on the border of Tulskaya and Orlovskaya guberniyas to the Boborykino station. Pouring rain. Early evening, the inn by the road and some kind of man at the doorway, using whip to clear his top-boots. Everything else clicked in so unexpectedly, that as I was starting it I couldn't guess how will it end," Bunin wrote in My Stories' Origins.[15]

- Muse (Муза) – Posledniye Novosty, No.6426, October 30, 1938. Paris. The story was inspired by another reminiscence, that of Bunin's mother's estate in Ozerki. The house, depicted in the story, was real, all the characters fictional.[16]

- The Late Hour (Поздний час) – Posledniye Novosti, No.6467, December 11, 1938, Paris.

Volume 2

- Rusya (Руся). Novy Zhurnal (New Journal), No.1, April–May 1942, New York. "That is a common thing with me. Once in a while would flicker through my imagination – some face, part of some landscape, a kind of weather – and then disappear. Occasionally it would stay, though, and start demanding my attention, asking for some development," Bunin wrote, remembering the way this short story's original image appeared.

- A Beauty (Красавица), A Simpleton (also: A Half-wit, Дурочка). Both in Novoselye magazine, No.26, April–May 1946, New York.

- Antigona (Антигона), Emerald (Смарагд), Calling Cards (Визитные карточки), Tanya (Таня), In Paris (В Париже). Stories written exclusively for Dark Alleys.

- Wolves (Волки). Novoye Russkoye Slovo (New Russian Word), No.10658, April 26, 1942. New York.

- Zoyka and Valerya (Зойка и Валерия). Russian Collection (Русский сборник), Paris, 1945.

- Galya Ganskaya (Галя Ганская). Novy Zhurnal, Vol. 13, 1946. New York. "The whole story is fictional, but the artist's prototype was Nilus", Vera Muromtseva-Bunina wrote in a letter to N.Smirnov (January 30, 1959). Pyotr Nilus was Bunin's friend in Odessa.

- Heinrich (Генрих). Dark Alleys. According to Vera Muromtseva-Bunina, Genrich's prototype was a real woman. "That was Max Lee, a journalist and writer who wrote novels in tandem with her husband. Their real surname was Kovalsky, if I remember correctly."[17][18]

- Natalie (Натали). Novy Zhurnal, No.2 1942, New York. Bunin heavily edited the original text while preparing it for the second, Paris edition. Of the initial idea he wrote: "I asked myself: very much in the same vein as Gogol who'd come up with his travelling dead soul merchant Chichikov, what if I invent a young man who travels looking for romantic adventure? I thought it was going to be a series of funny stories. But it turned out something totally different."[19]

Volume 3

- Upon a Long-Familiar Street (В одной знакомой улице). Russkye Novosti, Paris, 1945, No.26, November 9. In this newspaper issue one page was entirely devoted to Ivan Bunin's 75th birthday.

- Riverside Inn (Речной трактир). Novy Zhurnal, New York, 1945, Vol.1. Published in New York as a single brochure with Mstislav Dobuzhinsky's illustrations.[20]

- Madrid (Мадрид), The Second Pot of Coffee (Второй кофейник) . Both in Novoselye, New York, 1945, No.21.

- A Cold Autumn (Холодная осень). Russkye Novosty, Paris, 1945, No.1, May 18. Inspired, arguably, by Afanasy Fet's poem "What a cold autumn!.." (Какая холодная осень!..)

- The Raven (Ворон). Russkye Novosti, Paris, 1945, No.33, December 28. Soviet critic A. Tarasenkov in a foreword to the Selected Bunin (ГИХЛ, 1956, p. 20) mentioned this short story among Bunin's best work written in emigration. Later Thomas Bradly, in his introduction to Bunin's The Gentleman from San Francisco and Other Stories (1963, New York, Washington, Square Press, XIX, p. 264) argued that the writer's best short stories of the 1930s and 1940s were "Dark Alleys" and "The Raven".

- The Steamer Saratov (Пароход Саратов).

- The Camargue (Камарг).

- Beginnings (Начало).

- Mother in Law (Кума).

- The Oaklings (Дубки).[21]

- Revenge (Месть). Novy Zhurnal, New York, 1946, No.12.

- The Swing (Качели). Russkye Novosty, Paris, 1945, No.26, November 9.

- Pure Monday (Чистый Понедельник). Novy Zhurnal, New York, 1945, Vol.10. Vera Muromtseva recalled having found a scrap of paper (after one of her husband's sleepless nights) on which he wrote: "I thank you, God, for enabling me to write 'Pure Morning'". (Letter to N.P. Smirnov, January 29, 1959). "This short story Ivan Alekseevich rated as his best ever," she wrote in a letter to L.Vyacheslavov on September 19, 1960.

- One Hundred Rupees (Сто рупий), The Chapel (Часовня). Both previously unpublished.

- Judea in Spring (Весной в Иудее). Russkye Novosti, Paris, 1946, No.49. April 19. This short story gave its title to a Bunin's last in-his-lifetime collection, published in New York in 1953.

- A Night Stay (Ночлег). Judea in Spring, The Rose of Jericho.

English translations

- Dark Avenues and Other Stories. Translated by Richard Hare. Published by John Lehmann. London, 1949.

- Dark Avenues (Oneworld Modern Classics). Hugh Aplin, 2008

References

- ↑ Mikhailov, Oleg. The Works by I.A.Bunin. Vol.VII. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. 1965. Commentaries. P. 355

- ↑ Eros and Nirvana in the Art of Bunin, by James B. Woodward, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Jul., 1970), pp. 576–586

- ↑ Sedykh, Andrey. The Distant and the Close (Далекие, близкие). New York, 1962, p. 210

- ↑ Mikhailov, p.365

- ↑ И. Бунин. Темные аллеи. Первое издание. – Dark Alley's first edition, 1943.

- ↑ O.Mikhailov, p.364

- ↑ Mikhailov, pp.372–373

- ↑ Adamovich, Georgy. Loneliness and Freedom. Chekov Publishers, New York, p.115.

- ↑ Mikhailov, p.376

- ↑ Mikhailov, p.367

- ↑ Russkiye Novosty, Paris, 1961, November 17.

- ↑ Dark Avenyes. One World Classics edition Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine (first 19 pages)

- ↑ Sedykh, p.215

- ↑ Grechaninova, V. The Works by I.A.Bunin. Vol.VII. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. 1965. Commentaries. P. 383

- ↑ Grechaninova, p.384

- ↑ Grechaninova, p.385

- ↑ Rysskye Novosti, Paris, 1964, No.984, April 10.

- ↑ V. Grechaninova, p.387

- ↑ Grechaninova, p.388

- ↑ Grechaninova, p.389

- ↑ Grechaninova, p.389