| Darlaston | |

|---|---|

Darlaston town centre | |

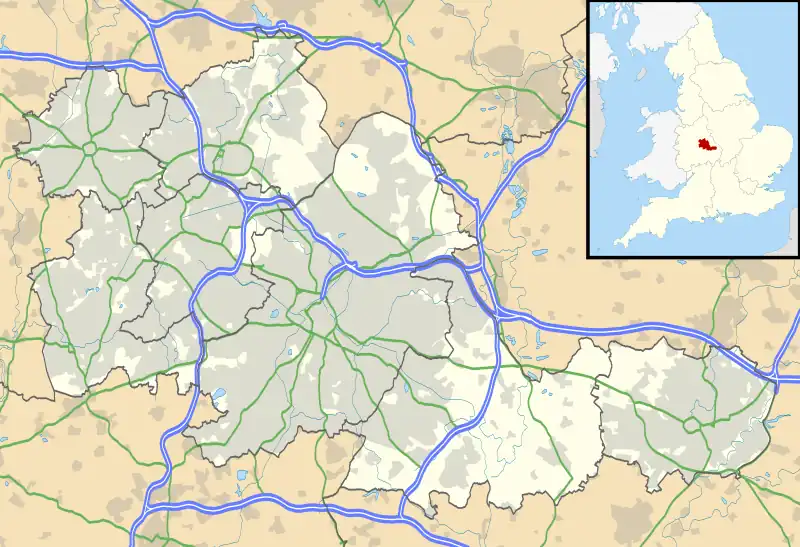

Darlaston Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 27,821 (2011.Wards)[1][2] |

| OS grid reference | SO9797 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Areas of the town (2011 census BUASD) | |

| Post town | WEDNESBURY |

| Postcode district | WS10 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Darlaston is an industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Walsall in the West Midlands of England. It is located near Wednesbury and Willenhall.

Topography

Darlaston is situated between Wednesbury and Walsall in the valley of the River Tame in the angle where the three major head-streams of the river converge. It is located on the South Staffordshire coalfield and has been an area of intense coal-mining activity. The underlying coal reserves were most likely deposited in the Carboniferous Period.

Disused coal mines are found near Queen Street in Moxley, behind Pinfold Street JMI School, near Hewitt Street and Wolverhampton Street, in George Rose Park and behind the police station in Victoria Park.

Mining subsidence, which has taken its toll on many buildings across central England, has also made its mark in Darlaston. In 1999, a council house on the New Moxley housing estate collapsed down a disused mineshaft, its occupant, an elderly man had complained of creaking and groaning in the house to neighbours who alerted the authorities. They in turn instructed him to leave. A few hours later it collapsed down the mine. The adjoining house also had to be demolished.

History

The ancient origins of the town are now very obscure due to the archive record being relatively recent. Any archaeological evidence has been largely destroyed due to intensive coal mining during the 18th and 19th centuries. A possible Saxon castle probably existed at Darlaston, which eventually became a timber castle.[3] No remains exist today.

Between the 12th and 15th centuries the de Darlaston family were the landowners, When the de Darlaston family died out, the manor was taken over by the Hayes family and was known as Great Croft.

Darlaston's location on the South Staffordshire coalfield led to the early development of coal mining and associated industrial activities. At first such activity was relatively small scale requiring only a copyhold permission from the lord of the manor. So, for example, in 1698 Timothy Woodhouse was manager of the coal mines belonging to Mrs. Mary Offley, then the lady of the manor. In the first year, he sold 3,000 sacks of coal and later went into partnership in his own business.

Rapid industrial growth in the early decades of the 19th century brought with it problems of housing, poverty and deprivation. In December 1839, the rector of the parish reported that there were approximately 1,500 homes in the parish of Darlaston, most of which were in poor condition and owned by working-class people. In 1841 the town had a population of 6,000. Development was driven by the presence of excellent transport links: the Birmingham Canal Navigations and Grand Junction Railway.[4] Much of the mining land was owned by the Birmingham Coal Company. Artist Thomas F. Worrall was born in the Woods Bank area in 1872, where his father worked as a blacksmith.

Notable beneficiaries of nineteenth-century industrialisation were the Rose family whose fortune had been made by astute enclosure of common land. Upon the death of Richard Rose in 1870 his estate was valued at over £877. He bequeathed the land to his wife Hannah. His brother was James Rose, shown in the 1871 census as a latch, bolt and nut maker, employing 39 people, including 19 children. By the time of the 1881 census, James Rose was 55 and his business had expanded to employ 90 people.[5] James Rose died in 1901.[6]

On 1 January 1895 Darlaston became an urban district, and the local board became Darlaston Urban District Council. In 1966, Darlaston became part of Walsall and in 1974, it became part of the metropolitan county of the West Midlands.[7]

Darlaston was subject to a number of bombing raids in World War II. A Luftwaffe bombing on 5 June 1941 wrecked several council houses in Lowe Avenue, Rough Hay, and killed 11 people. The bomb had been aimed at Rubery Owen's factory but missed by some distance. The houses were later rebuilt.[8]

Many Victorian terraced houses were demolished during the second half of the 20th century, and the Urban District Council of Darlaston built thousands of houses and flats to replace them with. From 1966 Darlaston was administered by Walsall borough and is now in the WS10 postal district which also includes neighbouring Wednesbury. However, since 1999 the council-owned housing stock has been controlled by Darlaston Housing Trust. In 2001 two of the town's four multi-storey blocks of flats were demolished, and the remaining two were demolished in 2004. .

By the end of the 1980s most of the industry in the town had closed and the town is now considered a ghost town, with an increasing high level of unemployment. In 2011 a total of 15 derelict sites in the town were designated as enterprise zones offering tax breaks and relaxed planning laws to any businesses interested in setting up bases in the selected areas. These enterprise zones are expected to create thousands of jobs and ease the town's long running unemployment crisis, which has deepened since 2008 as a result of the recession.[9]

Education

The town is served by one large secondary school, Grace Academy, which until 2009 was known as Darlaston Comprehensive School. It is situated in the west of the town near the border with Bilston.

Notable buildings

All Saints church

All Saints' Church, Darlaston (built 1872) was destroyed by enemy air raids in July 1942. A new church opened in 1952, designed by local architect Richard Twentyman. It is Grade 2 listed.

Bentley Old Hall

Bentley Old Hall stood in the north of Darlaston until the early 20th century. Bentley Hall was one of several country houses where in 1651 – after the Battle of Worcester – the future Charles II was sheltered, here by Colonel John Lane. The future king finally escaped disguised as the servant of Jane Lane, the colonel's sister. Bentley Old Hall grounds were redeveloped as a housing estate in the 1950s.[10]

Darlaston Manor House

The location of the manor house is believed to be congruent with the Asda supermarket car park, slightly south west of the original parish church, now St Lawrence's Church.[11]

Darlaston Town Hall

This attractive Queen Anne Style building in Victoria Road was designed by the Birmingham architect Jethro Anstice Cossins (1830–1917), and it was opened in 1888, built on the site of one of the town's two workhouses. It comprised municipal offices, a public library and a public hall.[12] Between 2006 and 2008 the building was restored by Walsall Borough Council at a cost of about £400,000. The main building now houses local Social Services departments, while the hall continues to be used for public meetings, concerts of music and other entertainments.[13]

The pipe organ

By 1903 the public hall was adorned with a fine new pipe organ, a gift to the town from the widow of James Slater, an ex-chairman of the Local Board, in his memory. The instrument was built by the West Yorkshire firm of J. J. Binns and was fully reported in the Musical Times.[14] The organ is still in use.[15] In June 2018 the Darlaston Town Hall pipe organ was recognised of outstanding national importance by the British Institute of Organ Studies (BIOS) – the UK's amenity society for pipe organs – and is listed as Grade 1 in the UK Historic Organs Scheme for being: an unaltered example of a town hall organ of 1903 by J. J. Binns and from the firm’s finest period.[16]

Darlaston Windmill

Darlaston had its own windmill from as early as 1695, when it appears on a map of that date. The mill continued to be in use until about 1860.[17]

St Lawrence Darlaston

The fine looking Grade-II listed St Lawrence's church as we see it today is largely late nineteenth century – the work of A. P. Brevitt – but the site dates back to early medieval times.[18] The church registers date back to 1539 and may be viewed at the County Archives in Stafford. The Bishop's Transcripts are to be found at Lichfield Record Office.[19]

A generous grant from the UK Heritage Lottery Fund enabled the complete redecoration of the church's interior in 2018.[20]

Notable residents

- Sue Nicholls (born 1943), actress known for soap operas including Coronation Street. The family-owned White Lion pub is situated in the Fold Darlaston.[21][22]

- John Fiddler (born 1947), musician and Medicine Head member[23]

- Mark Rhodes (born 1981), runner-up in ITV's Pop Idol in 2003, and children's television presenter[24]

Sport

- Billy Annis (1874–1938), former defenceman for the Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C., 1898-1905

- Jimmy McIntyre (1881–1954), former football manager and footballer who started his playing career at Darlaston Town[25]

- Syd Gibbons (1907–1953), professional footballer[26]

- Graham Hawkins (1946–2016), former footballer and manager of Wolverhampton Wanderers[27]

- Stuart Elwell (born 1977) professional boxer and former Midlands Welterweight Champion[28]

- Mark Lewis-Francis (born 1982), former sprinter[29]

- Netan Sansara (born 1989), footballer known for being the first Asian to play for the England U-18 team. His grandfather owned two pubs in Darlaston: The Three Horse Shoes and The Duke of York[30]

Neighbourhoods

- Rough Hay: a predominantly interwar council housing area in the north of the town close to the border with Willenhall.

- Moxley: an established private and council residential area in the west of the town close to the border with Bilston.

- Kings Hill: east of the town centre; a mixed residential area with an important British Asian population. Includes many types of housing as well as several factories and business units.

- Woods Bank: a predominantly interwar council housing area in the south of the town close to the border with Wednesbury.

- Bentley: the most northerly area in Darlaston which was mostly developed after 1945 but is now included in the Walsall postal district.

- Darlaston Green: Mixed residential and Industrial area, close to the border with Rough Hay and Bentley.

Public transport

Buses

Buses which serve Darlaston Town Centre stop at Darlaston Town Bus Interchange. Services run to Lodge Farm, Bentley, Willenhall, The Lunt, Bilston, Wolverhampton, Moxley, Walsall, Pleck, Wednesbury, and West Bromwich, and are operated by National Express West Midlands and Diamond Bus.

Additional services to Bilston, Ettingshall, Moxley, and Wednesbury briefly enter without calling at the main bus interchange.

Canals

The 7 Mile Walsall Canal runs through the town forming part of the Birmingham Canal Navigations.

Rail

- A new station for Darlaston is planned to open in 2023 which will connect Walsall to Wolverhampton running through Darlaston on the Walsall to Wolverhampton line.

- Darlaston railway station closed in 1887 and there is little evidence of its existence at the site, although the former trackbed is in use as a footpath.

- Darlaston James Bridge railway station closed in 1965 and there is little evidence of the existence at the site.

Roads

Since the early 1970s, the town centre has been by-passed by St Lawrence's Way, which runs between The Green and Bull Stake. No motorway runs through the town, but a section of the M6 between J9 and J10 may be considered to be in Darlaston.

Trams

Since 1999 there has been a West Midlands Metro stop at Bradley Lane in the Moxley area of the town. An initial plan was for the Metro to have a stop in Picturdrome Way using the old Darlaston railway line but this was abandoned.

Recreation

The town has a few small open spaces such as the playing fields at Broadwaters Road and three parks: Kings Hill Park, George Rose Park and Victoria Park.

Sports clubs

The town is represented in football by Darlaston Town (1874) FC who currently compete in the West Midlands (Regional) League. The town's football club used to be Darlaston Town FC, but the club went out of business in 2013.

References

- ↑ "Bentley and Darlaston North Ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ "Darlaston South Ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ King, D.J.C., 1983, Castellarium Anglicanum (London: Kraus) Vol. 2 p. 452

- ↑ William Foot; Geraldine Beech; Rose Mitchell (2004). Maps for Family and Local History: The Records of the Tithe, Valuation Office and National Farm Surveys of England and Wales, 1836 – 1943. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 101. ISBN 1-55002-506-6.

- ↑ William Foot; Geraldine Beech; Rose Mitchell (2004). Maps for Family and Local History: The Records of the Tithe, Valuation Office and National Farm Surveys of England and Wales, 1836 – 1943. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 102. ISBN 1-55002-506-6.

- ↑ William Foot; Geraldine Beech; Rose Mitchell (2004). Maps for Family and Local History: The Records of the Tithe, Valuation Office and National Farm Surveys of England and Wales, 1836 – 1943. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 103. ISBN 1-55002-506-6.

- ↑ Bev Parker. "A New Town Hall". A Brief History of Darlaston. University of Wolverhampton. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Darlaston". Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ↑ "Firms line up to move on Darlaston Enterprise Zone".

- ↑ The Redisovery of Bentley Hall, Walsall by Michael Shaw and Danny McAree (2007); online resource, accessed 1 July 2018

- ↑ Bev Parker. "Beginnings". A Brief History of Darlaston. University of Wolverhampton. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ 'Town Hall, Victoria Road' in Darlaston's Listed Buildings by Bev Parker (no date); online resource accessed 1 July 2018

- ↑ 'A New Town Hall' in A Brief History of Darlaston by Bev Parker (no date); online resource accessed 1 July 2018

- ↑ ‘A report of the new organ’ [at Darlaston], in The Musical Times, 1 December 1903. Wikimedia Commons source, accessed 10 April 2019

- ↑ 'A New Town Hall' in A Brief History of Darlaston by Bev Parker (no date); online resource accessed 1 July 2018

- ↑ "Staffordshire Darlaston, Town Hall, Victoria Road [N04970]", National Pipe Organ Register, British Institute of Organ Studies; online resource accessed 1 July 2018

- ↑ Bev Parker. "Early Growth". A Brief History of Darlaston. University of Wolverhampton. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ ‘St Lawrence’s Church Building’ Archived 4 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine in parish website. Online resource accessed 18 July 2018.

- ↑ ‘The church of St Lawrence’, A brief history of Darlaston: churches and chapels by Bev Parker (no date). Online resource, accessed 18 July 2018.

- ↑ ‘The parish church of St Lawrence’ in Bagnalls Group of Companies. Online resource accessed 18 July 2018.

- ↑ King, Danni (1 February 2022). "Coronation Street's Sue Nicholls' life off screen including co-star husband". OK!. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Chinn, Carl. "Recollections of Darlaston". Wolverhampton History and Heritage. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. p. 829. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- ↑ "Mark Rhodes warms up for Dancing on Ice debut". Express & Star. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ "SUPREMOS: Jimmy McIntyre". Coventry City Football Club. 14 July 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Matthews, Tony (15 August 2013). Manchester City Player by Player. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445617374. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Keen, Liam (24 August 2022). "Five decades in football – a new book on Wolves favourite Graham Hawkins". Shropshire Star. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ "Elwell guns for the British title". Express & Star. 24 January 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ "Mark Lewis Francis returns to old school to encourage pupils". Birmingham Mail. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Hugman, Barry J., ed. (2010). The PFA Footballers' Who's Who 2010–11. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-84596-601-0.