| Darnestown Presbyterian Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| 39°6′12.1″N 77°17′9.2″W / 39.103361°N 77.285889°W | |

| Location | 15120 Turkey Foot Rd Darnestown, Maryland, U.S. |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Simplified Greek Revival |

| Completed | 1858 |

The Darnestown Presbyterian Church dates back to the 1850s, and is located in Darnestown, Maryland. It is a Presbyterian Church (USA) congregation and a member of the National Capital Presbytery. Behind the church building is a cemetery with the graves of many of the early settlers of western Montgomery County, and some of the local roads and villages are namesakes of members of those pioneering families. The first European landowner in the Darnestown area was Ninian Beall, who settled around 1749. Some Beall family members are buried in the church cemetery.

Construction of the church began in 1855, after community leader John L. DuFief donated three acres (1.2 ha) of land. The cornerstone was laid on September 14, 1856, and a small vernacular frame building with no steeple and no stained-glass windows was constructed. The completed church was dedicated on May 22, 1858. In 1897, a bell tower and parlor were added. Improvements in 1952 and 1953 included expansion of the building, stained glass windows, and a Hammond organ.

Today (2022), the church has about 350 members and is active in the community. The church and cemetery are located close to the intersection of Darnestown Road and Turkey Foot Road.

History and background

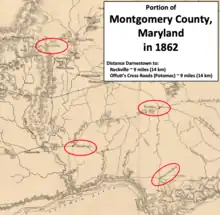

Ninian Beall was the first European landowner in what would become Maryland's Darnestown area, settling around 1749.[1] Originally, the land around present-day Darnestown was used by European settlers for growing tobacco and corn. In the last half of the 18th century, a small village grew at the Montgomery County intersection of what is now Darnestown Road (Maryland Route 28) and Seneca Road (Maryland Route 112).[Note 1] Seneca Road led from Darnestown to the Seneca Mill and a landing on the Potomac River—a trip of less than four miles (6.4 km).[3][4] During the first half of the 19th century, a new network of roads, mills, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) provided farmers with better access to markets.[5]

Darnestown's Presbyterians originally shared a log church with Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians. The church building was called the "Free Church" or the "Union Church", and it was located at the Pleasant Hills side of Darnestown.[6] The nearest Presbyterian Church was established in Neelsville in 1845, and it shared its minister with the Darnestown worshippers.[7] Neelsville was located 10 miles (16 km) north of Darnestown, but when traveling by road the trip was 20 miles (32 km).[7][Note 2] On May 12, 1855, the congregation of Darnestown Presbyterians became a "missionary Point" of the Neelsville Presbyterian Church.[6] Throughout the summer of 1855, the Darnestown Presbyterians sought ways to establish their own church building. Major George Peter offered land, but the location was unfavorable and therefore not pursued.[9] Shortly after Peter's offer, mill owner John L. DuFief donated three acres (1.2 ha) of land for the church.[10] The offer was accepted, and the land was located on Turkey Foot Road near Darnestown Road.[11][Note 3]

Construction and surroundings

The church's cornerstone was laid on September 14, 1856.[10] Funding was an issue for the small Darnestown congregation, and the new church was built with standard lumber. To save money, a bell tower and stained glass windows were not part of the original structure.[9] A ceremony was held to dedicate the completed church on May 22, 1858.[10] The original portion of the church has been described as an "example of Greek Revival church architecture" because of its "classical pilasters and pedimented windows."[10] The building was expanded in the late 1890s, and a bell tower and church parlor were added to the front of the structure. The front section's trussed and bracketed door hood is a simplified characteristic of Gothic Revival, as are the pointed arch windows.[10] Stained glass windows were installed in 1905, and a rear wing was added in the 1950s.[13][10] A new Hammond organ was purchased in 1953.[14]

Andrew Small

Andrew Small was a Scottsman living in Georgetown that became familiar with Darnestown while his company was helping construct the C&O Canal. In December 1865, Small granted the church $5,000 (equivalent to $95,587 in 2022) with three conditions.[15] First, the original sum of money was not to be spent. Second, the interest generated by the original funds would be used for paying a portion of the church pastor's salary. Third, the church congregation would decide the location of a parsonage by January 1, 1867, and a house would be erected for a pastor who would devote at least three fourths of his work in the Darnestown neighborhood.[15]

Small made another grant when he died in 1867. He left $35,000 (equivalent to $669,109 in 2022) to the Neelsville and Darnestown Presbyterian Church.[15] This time, there were no conditions, but it was understood that a portion of the money would be used to fund a private academy in Darnstown. After deducting the cost of the academy, the endowment was about $27,000 (equivalent to $516,170 in 2022) that was shared equally by the Darnestown and Neelsville branches.[15]

Academy

"The academy grounds contain six or seven acres filled with shade trees, and offer ample room for out-door exercise. The school is intended for both sexes, and is provided with two large schoolrooms and smaller class-rooms."

Where to Educate, 1898-1899: A Guide to the Best Private Schools....[16]

The Darnestown congregation acquired land, located next to the church land, for a manse and the academy.[15] Construction work for the manse and academy was conducted at the same time. The manse was ready to be occupied in February 1870, but was part of a dispute between the Darnestown and Neelsville churches. The Presbytery settled the dispute with each branch having its own minister.[15]

The academy, which was named the Andrew Small Academy, began in the basement of the church in 1867 before the academy building was completed.[17] The school was moved into its new building in 1869 before it was finished, but was forced to close during 1871 because of financial problems. The school restarted in 1872.[17] The building was a three-story brick structure that was completed in 1872.[18] It was the largest school building in Montgomery County, and taught boys and girls.[19] During the early 1880s, it had about 60 students, and about one third of the students were boarders.[19] The school's principal was the church's minister until 1892.[17] In 1907, the county obtained use of the academy building for a public high school.[18][Note 4]

Cemetery

The church's cemetery contains the graves of some of the area's early settlers, including members of the Darne, Clagett, Offutt, and Tschiffely families.[13] Some members of the Beall family were also buried there in the 1800s.[20] The Clagett family, also spelled Claggett, is associated with the nearby neighborhood of Quince Orchard. The community of Travilah, Travilah Road, and Travilah Elementary School are all named after Travilah Clagett.[21] The Offutt family is associated with the community known as Potomac, which was originally called Offutt's Crossroads.[22] The Tschiffely family is associated with the nearby Kentlands neighborhood, and also owned a mill near the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal).[23] Three of the closest C&O Canal locks are the Pennyfield Lock, Riley's Lock, and Violette's Lock—and all three of their namesake lock keepers are buried at the cemetery. Philanthropist Andrew Small, who left money for the church and a school during the 1860s, is also buried there.[10]

Current use

The Darnestown Presbyterian Church has about 350 members (2022). Sunday School starts at 9:00 am and worship service at 10:30 am. During the summer, worship service starts at 9:30 am. Worshippers can also view services on-line on the church's YouTube channel.[24] Services are led by the Reverend Neill S. Morgan.[25] The church is located at the intersection of Darnestown Road and Turkey Foot Road. At one time, it used an address of 13800 Darnestown Road, but its current address is 15120 Turkey Foot Road.[26]

The Andrew Small Academy was demolished in 1955. Darnestown Elementary School stands in its place at 15030 Turkey Foot Road. The exact site of the academy is now covered by a blacktop play area behind the elementary school.[27]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Maryland's Montgomery County was established in 1776 when Frederick County was split into three counties.[2]

- ↑ In 2021, Neelsville was still considered a populated place by the United States Geological Survey.[8] However, the completion of a railroad line one mile (1.6 km) east in 1873 caused the village to mostly disappear and it was eventually absorbed by Germantown.[7]

- ↑ DuFief was an architect, farmer, and owner of the DuFief Mill located on Turkey Foot Road. Present day Dufief Mill Road (now without the "F" capitalized) was one of the roads that led to DuFief's Mill.[12]

- ↑ Montgomery County purchased the academy land in 1927. The building was eventually demolished, and Darnestown Elementary School was constructed on the site in 1954.[18]

Citations

- ↑ "Maryland Historical Trust Determination of Eligibility Form - Darnestown Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ↑ Montgomery County, Maryland & Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, p. 3

- ↑ "Capsule Summary Seneca Creek State Park" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland government. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ↑ Fielding Lucas, Jr. (1841). Map of the State of Maryland (from Lib. of Congress) (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Fielding Lucas, Jr. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 12

- 1 2 Wells 1980, p. 2

- 1 2 3 "Maryland Historical Trust - Neelsville Presbyterian Church Germantown Chapel" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ "Neelsville". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. September 11, 1979. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- 1 2 Wells 1980, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 218

- ↑ "Darnestown Presbyterian Church & Cemetery" (PDF). Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ "Maryland Historical Trust - Dufief Mill Site" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- 1 2 Scharf 1882, pp. 761–762

- ↑ Wells 1980, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wells 1980, p. 5

- ↑ Knudson 1898, p. 116

- 1 2 3 Wells 1980, p. 6

- 1 2 3 Coleman & Lewis 1984, p. 74

- 1 2 Scharf 1882, p. 762

- ↑ "ACHS summary Form - James Brook Beall House (see 4th page of PDF)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 226

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 220

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 153

- ↑ "Darnestown Presbyterian - Start Here!". Darnestown Presbyterian Church. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Darnestown Presbyterian - Staff and Leadership". Darnestown Presbyterian Church. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Darnestown Presbyterian Church and Cemetery" (PDF). Montgomery County Preservation Commission. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Andrew Small Academy Site" (PDF). Montgomery County Preservation Commission. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

References

- Coleman, Margaret Marshall; Lewis, Anne Dennis (1984). Montgomery County: A Pictorial History. Norfolk, Virginia: Donning Company. ISBN 978-0-89865-516-2. OCLC 18292502.

- Curtis, Shaun (2020). Around Gaithersburg. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-46710-462-3. OCLC 1124337558.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- Knudson, Grace P. T. (1898). Where to Educate, 1898-1899: A Guide to the Best Private Schools, Higher Institutions of Learning, etc., in the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Brown and Company. OCLC 1002881300. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- Montgomery County, Maryland; Montgomery County Historical Society (1999). Montgomery County, Maryland – Our History and Government (PDF). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government Office of Public Information.

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1882). History of Western Maryland: Being a History of Frederick, Montgomery, Carroll, Washington, Allegany, and Garrett Counties from the Earliest Period to the Present Day; Including Biographical Sketches of their Representative Men. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: L.H. Everts. OCLC 2955029. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Wells, John F. (1980). A History of the Darnestown Presbyterian Church. [not identified]: [not identified]. OCLC 53463904.