A data ecosystem is the complex environment of co-dependent networks and actors that contribute to data collection, transfer and use.[1] They can span across sectors - such as healthcare or finance, to inform one another's practices.[2] A data ecosystem often consists of numerous data assemblages.[3] Research into data ecosystems has developed in response to the rapid proliferation and availability of information through the web, which has contributed to the commodification of data.[1]

Data

Data refers to digitized information that is compressed for efficient transmission.[4] Data is constituted of binary values, expressed as 1 or 0, which allows complex thoughts, images, videos and more to be abstracted.[4] The level of data production and exchange has exploded in recent decades, with government and public agencies freely publishing vast swaths of data, particularly in environmental, cultural, scientific and statistical fields.[1] It has also led to a highly profitable industry for companies that collect, categorize and disseminate data as a tradable resource and operate within the newly defined data ecosystems.[1]

Data ecosystems

The nature of an ecosystem denotes a symbiotic relationship between elements. Thus, when describing a data environment as an ecosystem, it describes a co-constitutive relationship. Their primary purpose is to create, manage and sustain the sharing of data across platforms and disciplines.[1] Key to this initiative are data intermediaries, which facilitate access to the data, and are categorized into seven types, including data trusts, data exchanges and data platforms.[2][5] A data ecosystem also comprises data providers and consumers, who as their titles denote, provide and consume the data through the intermediaries.[3]

A common example of data ecosystem exists within the realm of web browser. A third-party tracking app on a website (referred to as cookies) acts as an intermediary by collecting and organizing data. The web browser becomes the data provider, as it shares a user's information as they navigate through different websites. The websites themselves become consumers as they utilize the tracking information to tailor content based on user behaviour.[6]

As mentioned, data ecosystems can span across sectors, for example, a client's medical data is shared with an insurance company to calculate a premium. The point of an ecosystem is that all actors within the shared environment are contributing to a common resource or knowledge-base.[1]

Mapping

Data ecosystems possess three major characteristics: network, platform, and co-evolution.[1] Network loosely refers to the groups of data and technology developers, providers, and resellers.[1] The platform, then, is the service, tool or platform that is collaboratively used by the network of actors.[1] The platform provides the interface for the actors to produce their shared product or service.[1] The final characteristic refers to how the different actors and platform enable one another to evolve or improve upon itself.[1] The metaphorical use of the term ecosystem intrinsically demands that all parties involved are mutually benefited by their engagement. That would be the betterment or evolution of their own functioning, which leads to positive outcomes for the larger ecosystem. Again, to use the example of a web browser – the third-party tracking app collects data to help websites evolve their content strategies, which then provide more accurate user data to third-party trackers in an endless feedback loop.[6]

Data assemblages

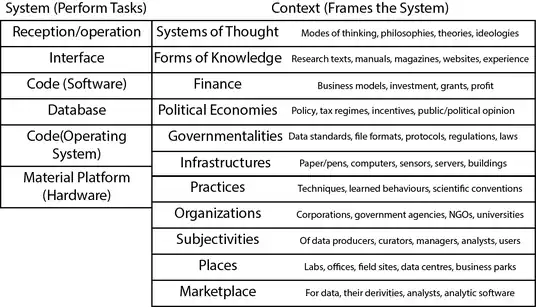

Within the broad landscape of a data ecosystem are numerous data assemblages. An assemblage is described as interconnected socio-technical systems that work in tandem with one another for a common purpose.[3] These systems encompass the technological, political, financial and best practices that sustain the collection, transfer, and dispersion of data.[8] The below table demonstrates the common elements of a data assemblage which facilitate and govern datafication.

A data ecosystem contains numerous data assemblages, as each actor within the system have their own sets of tangible and non-tangible elements for their operation. Web browsers as data providers have their own assemblages of hardware, software, servers, finances, infrastructure, practices, etc. Each website that consumes the data and the broader companies that they represent similarly present an assemblage of systems. And the intermediary tracking sites which collect and sell the data operate within their own assemblage. It is possible that different assemblages may share elements within the broader ecosystem, or have individual elements, such as opposing hardware or platforms, that come into conflict.[9] For example, a web browser may include ad blockers which conflict with the third-party trackers that attempt to scrape a user's data.

Big data

The rise of data ecosystems is part and parcel with the development of big data. Big data is an emerging trend in science and technology that tracks and defines almost all human engagement.[10] It is defined by the following five properties:

Volume

Big data consists of massive amounts of information, which could be terabytes or petabytes.[8]

Velocity

Big data is produced rapidly, and exchanged in real-time.[8]

Variety

Big Data are extremely diverse, constituting numerous fields of study, and with extensive practical applications.[8]

Value

Big data has inherent value due to the potential application of the data and the political economy in which it operates.[11]

Veracity

Big data must be considered accurate and of high-quality. This can be difficult, as information may be incomplete or wrong, but there should be a level of trust that the collection of the data was done with the intention of being truthful.[11]

Concerns

The main concern or critique of data ecosystems relates to privacy. Who has access to the data, either implicitly or explicitly? How is that data secured? How is it being used, and perhaps monetized? The non-profit organization Cloud Secure Alliance (CSA) categorizes the security challenges of Big Data Ecosystems into four groups; infrastructure security, data privacy, data management, and integrity and relative security.

In the case of a web browser, website and third-party tracking operation, there is a clear financial incentive for why data is collected and how it is used. But there is also a level of surveillance that occurs in this scenario, that perhaps goes unnoticed. Rob Kitchin terms this as 'dataveillance,' a result of the datafication of everyday life which allows for highly accurate and continuous tracking of our locations and activities.[3] Who else, besides those trackers and websites, has access to the data being collected, and is it used for more nefarious purposes? In the case of US states that have banned access to abortions, there's concern that these data ecosystems can be harnessed to penalize citizens that seek services out of state.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Oliveira, Marcelo Iury S.; Lóscio, Bernadette Farias (2018-05-30). "What is a data ecosystem?". Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1145/3209281.3209335. ISBN 978-1-4503-6526-0. S2CID 195348898.

- 1 2 Abdulla, Ahmed (March 8, 2021). "Data ecosystems made simple". McKinsey Digital.

- 1 2 3 4 Kitchin, Rob (2022). The data revolution : a critical analysis of big data, open data & data infrastructures (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-1-5297-3375-4. OCLC 1285687714.

- 1 2 Vaughan, Jack (July 2019). "data". TechTarget.

- ↑ Massey, Joe (August 18, 2022). "Data Institutions". Open Data Institute. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- 1 2 Freedman, Max (November 21, 2022). "Businesses Are Collecting Data. How Are They Using It?". Business News Daily. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ↑ Kitchin, Rob (2022). The data revolution : a critical analysis of big data, open data & data infrastructures (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 978-1-5297-3375-4. OCLC 1285687714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 P., Kitchin, Rob Lauriault, Tracey (2014-07-27). Towards critical data studies: Charting and unpacking data assemblages and their work. The Programmable City Working Paper 2. Programmable City. OCLC 1291151213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cui, Yesheng; Kara, Sami; Chan, Ka C. (April 2020). "Manufacturing big data ecosystem: A systematic literature review" (PDF). Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 62: 101861. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2019.101861. ISSN 0736-5845. S2CID 208832261.

- ↑ Demchenko, Yuri; de Laat, Cees; Membrey, Peter (May 2014). "Defining architecture components of the Big Data Ecosystem". 2014 International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS). Minneapolis, MN, USA: IEEE. pp. 104–112. doi:10.1109/CTS.2014.6867550. ISBN 978-1-4799-5158-1. S2CID 2920274.

- 1 2 Gillis, Alexander (March 2021). "5 V's of big data". TechTarget.

- ↑ Ng, Alfred (July 18, 2022). "'A uniquely dangerous tool': How Google's data can help states track abortions". Politico.