David Hawkins | |

|---|---|

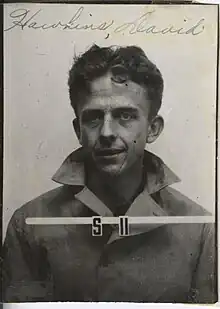

David Hawkins' Los Alamos ID badge | |

| Born | February 28, 1913 |

| Died | February 24, 2002 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Hawkins–Simon theorem |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Stanford University University of California, Berkeley |

| Thesis | A Causal Interpretation of Probability |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions | George Washington University University of Colorado |

David Hawkins (February 28, 1913 – February 24, 2002) was an American scientist whose interests included the philosophy of science, mathematics, economics, childhood science education, and ethics. He was also an administrative assistant at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory and later one of its official historians. Together with Herbert A. Simon, he discovered and proved the Hawkins–Simon theorem.

Early life

David Hawkins was born in El Paso, Texas, the youngest of seven children of William Ashton Hawkins, and his wife Clara née Gardiner.[1] His father was a prominent lawyer noted for his work on water law,[2] who worked for the El Paso and Northeastern Railway,[3] and was one of the founders of the city of Alamogordo, New Mexico.[1] He grew up in La Luz, New Mexico.[2]

Hawkins attended Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut, but left after his junior year to enter Stanford University.[1] He initially studied chemistry, but then switched to physics before finally majoring in philosophy.[4] He was awarded his B.A. in 1934 and M.A. in 1936.[1] While he was there, he met Frances Pockman,[5] a teacher and writer.[1] They got married in San Francisco in 1937. They had a daughter, Julie.[4]

In 1936, Hawkins went to the University of California, Berkeley, to work on his doctorate.[6] He became friends with Robert Oppenheimer, with whom he liked to discuss Hindu philosophy and issues in the philosophy of science such as the uncertainty principle and Niels Bohr's complementarity. In 1938, Hawkins and his wife, Frances, joined the Berkeley campus branch of the Communist Party of America.[4] He earned his Ph.D. in 1940, writing his thesis on "A Causal Interpretation of Probability".[4][7]

Manhattan Project

After graduating, Hawkins worked at Berkeley until May 1943, when Oppenheimer recruited him to work at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, as his administrative assistant.[1] "I was intrigued by the thought of being part of this extraordinary development," he later explained, "And it was still of course in those days entirely focused on the terrible thought that the Germans might get this weapon and win World War II."[8]

Hawkins saw his role as that of a go-between, mediating between the civilian scientists and the military leadership at Los Alamos,[2] but he also found a kindred spirit in the Polish mathematician Stan Ulam, who was working in Edward Teller's "Super" Group. They investigated the problem of branching a neutron multiplication in a nuclear chain reaction. Stan Frankel and Richard Feynman had tackled the problem using classical physics, but Ulam and Hawkins approached it using probability theory, creating a new sub-field now known as branching process theory.[9] They investigated branching chains using a characteristic function. After the war, Ulam would extend and generalise this work.[10] He described Hawkins as "the most talented amateur mathematician I know".[11]

Hawkins is credited with the selection of the Alamogordo area for the Trinity nuclear test,[1] but he declined to watch it.[8] His final assignment at Los Alamos was as its historian, writing the history of Project Y. He completed this work in August 1946, covering the history of Project Y up to August 1945, but it remained classified until 1961. He was a founding member of the Federation of American Scientists.[4]

Later life

With World War II over, he left Los Alamos to become an associate professor of philosophy at George Washington University, but left in 1947 to join the faculty at the University of Colorado Boulder.[4] Together with Herbert A. Simon, he discovered and proved the Hawkins–Simon theorem on the "conditions for the existence of positive solution vectors for input-output matrices".[8][12] This macroeconomic theorem helped economists better understand the interconnectedness of various sectors of an economy.[8]

On December 20, 1950, Hawkins was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee.[4] He testified that he had been a member of the Communist Party from 1938 to 1942.[8] The testimony of Hawkins and his wife Frances was released publicly in January 1951, resulting in an outcry led by The Denver Post. There were calls for his dismissal, but he had tenure and, under the university's law, this could only be revoked for incompetence or moral turpitude.[6] The regents took a vote, and were split evenly; the numbers went in his favor when one of them died.[1] He remained at the University of Colorado until he retired in 1982,[4] except for periods as a visiting professor at Berkeley, the University of North Carolina, Cornell University, Simon Fraser University, the University of Michigan and the University of Rome. He was also a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study and the American Council of Learned Societies.[5]

From 1962, Hawkins increasingly took an interest in early childhood education and in improving elementary school science education. With his wife Frances, they established the Elementary Science Advisory Center to improve the standard of science teaching, which he directed from 1965 to 1970. In 1970, they founded the campus-based Mountain View Center for Environmental Education with funding from the university and the Ford Foundation,[4] which provided advanced education for elementary school teachers.[5] He was a consultant to the National Institute of Education and the National Science Foundation.[4] In 1981, he received a $300,000 "genius grant" from the MacArthur Foundation.[1]

Hawkins died at his home in Boulder, Colorado, on February 24, 2002.[1] He was survived by his wife Frances and daughter Julie. His papers are in the library of the University of Colorado, Boulder.[4] In 2013, the University of Colorado hosted an interactive exhibit in Boulder about his life and work, Cultivate the Scientist in Every Child: The Philosophy of Frances and David Hawkins.[13] Over the following five years, the exhibit travelled to Wyoming, New Mexico, Nebraska, Illinois, Wisconsin, Tennessee, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and California, before arriving in its permanent home at Boulder Journey School in Boulder.[14]

Selected works

- Hawkins, David (1961). Manhattan District history, Project Y, the Los Alamos Project – Volume I: Inception until August 1945. Los Angeles: Tomash Publishers. ISBN 978-0-938228-08-0. LAMS-2532. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ——— (1964). The Language of Nature: An Essay on the Philosophy of Science. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. OCLC 525803.[15]

- ——— (1974). The Informed Vision, Essays on Learning and Human Nature. New York: Agathon Press. OCLC 301735786.

- ——— (1977). The Science and Ethics of Equality. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465072378. OCLC 2837081.

- ——— (2000). The Roots of Literacy. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870815959. OCLC 44391709.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (March 4, 2002). "David Hawkins, 88, Historian For Manhattan Project in 1940's". New York Times. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Woo, Elaine. "D. Hawkins, 88; Atomic Bomb Historian". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form – La Luz Townsite". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "David Hawkins Papers". University of Colorado Boulder Libraries, Special Collection, Archives and Preservation Department. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Obituary of David Hawkins". University of Colorado. March 7, 2002. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012.

- 1 2 Sherwin, Martin (1982). "Audio Interview with David Hawkins". Voices of the Manhattan Project. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ "A Causal Interpretation of Probability". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weil, Martin (March 2, 2002). "Philosopher David Hawkins Dies". Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Ulam 1983, p. 153.

- ↑ Ulam 1983, pp. 158–161.

- ↑ Ulam 1983, p. 159.

- ↑ Hawkins, David; Simon, Herbert A. (1949). "Some Conditions of Macroeconomic Stability". Econometrica. 17 (3/4): 245–248. doi:10.2307/1905526. JSTOR 1905526.

- ↑ "Cultivate the Scientist in Every Child Exhibit Explores Compelling Childhood Learning Approaches" (PDF). University of Colorado, Denver. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Throwback Thursday: Cultivate the Scientist in Every Child". Hawkins Centers. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Wheelock Hosts Hawkins Exhibit and Conference". Wheelock College. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Exhibit Location". Hawkins Centers of Learning. Retrieved February 8, 2017. - ↑ Lindsay, R. B., David (1965). "Review of The Language of Nature by David Hawkins". Physics Today. 18 (6): 58. doi:10.1063/1.3047491. ISSN 0031-9228.

References

- Ulam, Stanisław (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-14391-0. OCLC 1528346.

External links

- Sherwin, Martin (1982). "Audio Interview with David Hawkins". Voices of the Manhattan Project. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- "Messing About in Science" (PDF). Science and Children. National Science Teachers Association. 2 (5). February 1965. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- "Hawkins Centers of Learning". Hawkins Centers of Learning. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- Trailer: In the Child's Garden: The Educational Legacy of Frances & David Hawkins. Petite Productions. Retrieved February 8, 2017.