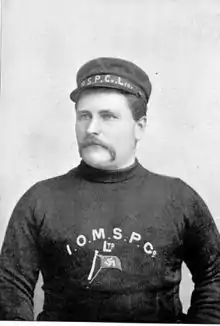

David "Dawsey" Kewley | |

|---|---|

David "Dawsey" Kewley | |

| Born | 1850 |

| Died | 25 March 1904 (aged 53–54) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Boatman |

| Employer | Isle of Man Steam Packet Company |

| Known for | Renowned life saver. Honoured on numerous occasions by the Royal Humane Society for his life-saving exploits. |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Cowley[1] |

| Children | David Kewley; Mary Kewley; Frances Kewley |

David "Dawsey" Kewley (1850 – 25 March 1904) was a Manx boatman, member of the Douglas Rocket Brigade and volunteer in the Lifeboat Service, renowned for his involvement in the saving of lives at sea. Reports of the number of people he saved from drowning vary. According to some contemporary reports he saved as many as 38 lives,[2] according to others 25,[3] but it is generally recognised that he was directly involved in saving the lives of at least 23 people, and as a member of the Douglas Lifeboat Crew assisted in the saving of many more. He was a recipient of numerous awards from the Royal Humane Society for his life-saving exploits.[4][5] Although a man of dauntless courage, he would never speak about his feats and disliked hearing other people talk about them.[2]

Biography

David Kewley (always known by his sobriquet of "Dawsey")[3] was born in Douglas, Isle of Man in 1850, the eighth of ten children and brought up in the tough Fairy Ground area of the town.[5] His father, also known as Dawsey, was a boatman and fisherman working an open lug-boat. After receiving a somewhat limited education the younger Kewley joined his older brother and father in the fishing trade.[6]

Regarded as singularly unassuming in character, modest, retiring and of a kindly nature, he took employment with the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company in 1877[7] as a boatman, living at 11, New Bond St, Douglas and later Shaw's Brow.

Well known as a highly accomplished oarsman and swimmer, Dawsey competed in numerous rowing regattas around the Isle of Man and the northwest of England gaining success on many occasions, not least[8][9] in the early 1870s, when as stroke oar of a crew which caused something of a sensation.[2] Turning up at an event with three colleagues; Charles Kewin, John Cain and Hugh Rogers[10] and an old gig which the four men had patched up themselves and known as "The Hobblers Boat,"[2] (the term "hobbler" applying to a waterman or pier porter) they competed in a race against several well trained racing crews, and to the astonishment of everyone, won easily.[2] In turn they raced against professional crews from Manchester and Dumbarton enjoying further success.[2] They twice won the Duke of Devonshire's prize at Barrow-in-Furness competing against, and beating, a celebrated crew of boatmen from Barrow who were stroked by the renowned Anthony Strong.

Dawsey was said to have been an ideal stroke oar. Average in height with a superb physique, he reached well forward and pulled his oar cleanly through the water, finishing powerfully.[10] As well as becoming the stroke oar of the premier Douglas four, Dawsey also competed in the pairs category with John Cain (Dawsey and Cain were never beaten in a paired-oar race) as well as individually in the sculls.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Rescues

Certain reports from contemporary sources cite what at the time was thought to be insufficient recognition towards the endeavors of Dawsey by the Royal Humane Society.[11] On various occasions it was questioned whether Dawsey had in fact received sufficient acknowledgement for his heroism, a fact supporting the assertion being that he'd "only" received certificates[11] when it was generally regarded that awards from the society such as gold, silver and bronze medals had been bestowed on individuals of higher social status for lesser endeavors.[11][12] One such person who was instrumental in trying to highlight this perceived short-coming was the High Bailiff of Douglas, Samuel Harris, who on several occasions described Dawsey as: "the bravest man in the town."[12][13] Following numerous letters written to the society by such as Samuel Harris, these concerns were addressed following a rescue which Dawsey was involved in on 28 July 1888, and for which his bravery was recognised by the awarding of a bronze medal.[14]

Detailed below are some of the various rescues in which Dawsey Kewley was involved:

18 October 1878

On the evening of Friday 18 October 1878, the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company steamer Snaefell was in the process of docking in Douglas Harbour when one of her passengers, Dr Hemming,[15] fell off the ship and into the harbour.[15] On witnessing the event, despite the darkness, Dawsey immediately jumped into the water and made towards the man, managing to take him towards a ladder by which he was able to support himself and Dr Hemming.[15] After approximately 20 minutes a boat arrived and took both Dawsey and Dr Hemming to safety.[15] Reports state that Dr Hemming was the third person which Dawsey had rescued within four months.[16] For saving the life of Dr Hemming, Dawsey Kewley received his first award from the Royal Humane Society.[17]

2 August 1879

On Saturday 2 August 1879, a harbour porter named Thomas Sheard fell into the water between two steamers which were docked alongside the Victoria Pier.[18] Again Dawsey immediately jumped into the water and performed a rescue, with complete disregard for his own safety.[18] The rescue of Sheard resulted in Dawsey receiving another award from the Royal Humane Society[18] accompanied by a written commendation on vellum:

"The Honorary Testimonial has been awarded to David Kewley by the Royal Humane Society, in recognition of his humane exertions on the 2nd day of August, 1879."

— Royal Humane Society (Instituted 1774). 4, Trafalgar Square, London W.C., 24th September, 1879.

The presentation was made by the High Bailiff of the Isle of Man at a ceremony on 25 October 1879.[3]

5 August 1882

Another incident involving a harbour porter occurred in Douglas Harbour, again concerning the steamer Snaefell on Saturday 5 August 1882, a scene witnessed by hundreds of people.[19] The Snaefell had arrived from Liverpool and was in the process of discharging its passengers when the porter, who was making his way onto the ship, fell into the water and was in danger of being drowned. A passenger on board the steamer in turn leapt into the water so as to render assistance, but he in turn quickly got himself into trouble.[19] Kewley was alerted to the situation and jumped into the water and managed to support the two men until a rope was thrown enabling the men to be lifted from the water.[19]

30 May 1884

A report of a further rescue was one of a small boy who had fallen into the inner harbour, Douglas, on Friday 30 May 1884.[20] The young boy, who had been playing in the vicinity of the steamer Tynwald,[20] fell into the water and due to an ebbing tide was being drawn under the vessel.[20] Dawsey managed to get to the young boy, after some initial trouble, and brought him safely to the surface and onwards to the shore.[20]

25 September 1884

A strange irony is that on one occasion it was Dawsey's life which had to be saved.[21] The incident occurred on the evening of Thursday 25 September 1884, when the steamer Ben-my-Chree was securing alongside the harbour wall.[21] Dawsey was part of a team of dockers positioning the gangway to the vessel when he slipped over, his head striking the Ben-my-Chree's sponson, and subsequently fell into the water.[21] Temporarily stunned, Dawsey sunk beneath the water, which led to the Ben-my-Chree's Third Officer, Dalzell Torrance, jumping into the water in order to save Dawsey. In time a rope was thrown to Third Officer Torrance, enabling him and the unconscious Dawsey to be pulled to the steps of the pier.[21]

The saving of Dawsey was the fourth time Dalzell Torrance had performed a life saving act.[21]

28 July 1888

Together with another Douglas boatman, John Lewin, Dawsey saved the life of a man who'd jumped off the Victoria Pier on Saturday 28 July 1888. Intent on self-harm, the man initially refused assistance which led to Dawsey jumping into the water followed by Lewin.[11] The man was in great difficulty in the water, however Dawsey and Lewin were able to support him and take him to the shore, from where he was taken to hospital.[11] In recognition for this rescue, both John Lewin and Dawsey received bronze medals from the Royal Humane Society.[22] The medals were presented to John Lewin and Dawsey by the Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Man, Sir Spencer Walpole, at a reception on 14 November 1888. A Testimonial Fund had also been created in recognition of Dawsey's bravery which had, through public donations, raised the amount of £41 and this was also presented to him at the ceremony.[14]

.jpg.webp)

9 August 1893

On the afternoon of Wednesday 9 August 1893, a young boy fell into the sea whilst fishing on the Victoria Pier and was subsequently rescued by Dawsey.[23]

13 September 1893

On the night of Wednesday 13 September 1893 the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company steamer, Peveril, was involved in a collision with a small boat as she was making her way from the Victoria Pier to the inner harbour at Douglas. The small boat, named the Daisy, was on its way to put a light on the yacht Vision when she cut across the Peveril's path, and was cut in two. The solitary person on board the Daisy, John "Kitty" O'Neil, jumped clear just before impact and was subsequently picked out of the water by three dockers; Dawsey, Paul Bridson and another man named Higgin, who took to a small boat in order to carry out the rescue.[24]

Death

Dawsey Kewley contracted pleurisy in February 1904. He was initially looked after at home, but was transferred to Noble's Hospital, Douglas, on Wednesday 23 March and died in the early hours of Friday 25 March.[2] His cause of death was given as pneumonia, which may well have been attributed to his numerous immersions in icy-cold water.[2]

Funeral

The funeral of Dawsey Kewley took place on the afternoon of Sunday 27 March 1904. It was an occasion of a demonstration of popular respect for a brave seaman, who had done so much for others in his lifetime.[25] Led by members of the Order of Foresters (Star of Mona), of which Dawsey was a member, and the Douglas Town Band, the cortege left his home at 1, Shaw's Brow, followed by a very large crowd to St Matthew's Church,[25] Douglas, where Dawsey had for many years been one of the foremost members of the congregation. The service was conducted by the Reverend T.A. Taggart, to whom Dawsey was known personally.[25] Those attending Dawsey's funeral included a large representation of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company led by Dalrymple Maitland and William Hutchinson[25] as well as the Mayor of Douglas, members of the Lifeboat Committee, the Douglas Swimming Club and the Victoria Swimming Club. Following the service Dawsey's body was taken for interment at Braddan Parish Cemetery.[25] Reports of the funeral state that the crowd of mourners stretched from the cemetery all the way back to the Quarterbridge.[25]

Dawsey's death was followed by that of his daughter, Frances Kewley, who died less than two months after him and was in turn interred with her father.[26] Dawsey had been pre-deceased by two of his children a son, David, and another daughter, Mary, both of whom had died in infancy.[26] Dawsey was survived by his wife and another son.[27]

The headstone on Dawsey's grave is that of Manx Runic Cross from a design by Manx artist Archibald Knox;[26] the work being carried out by Thomas Quayle & Sons, Douglas, Isle of Man.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Monument

Following Dawsey's death a meeting was held, presided over by the Mayor of Douglas,[2] at which it was decided that a monument was to be erected in his memory through public subscription.

The monument was erected by W. Cathcart of Glasgow and is made of Aberdeen granite.[28] It was originally a drinking fountain and water trough with the water issuing from the mouth of a stone lion. In the panel above the lion is a sculpture typifying one of Dawsey's rescues.[28] Originally situated at the apex of the Pier Buildings on the Victoria Pier[28] the monument was unveiled by the Deputy Governor of the Isle of Man, Deemster Thomas Kneen, on Thursday 8 June 1905.[28] Numerous civic dignitaries were in attendance and during the course of the ceremony two certificates from the Royal Humane Society were awarded to Samuel Webb, in recognition for his rescue of a young boy who's fallen into the sea off Douglas Promenade, and to G. Cowin for rescuing an elderly lady from Douglas Harbour.[28] At the moment of the unveiling salutes were fired from the Douglas Rocket Station and Douglas Head Lighthouse.[28]

Following the construction of the new Douglas Sea Terminal in the late 1960s the monument was sited for many years at the southern end of Douglas Promenade adjacent to a car park. It was moved to its current site in one of the promenade's sunken gardens following renovation work.[5]

A poem was also written in Dawsey's honour:[2]

Tis said that 38 were rescued by his hand,

Yet naught did he relate of all these exploits grand.

Oh, many have fame not half as brave as he,

A man who duty made his aim and waited silently.

References

- ↑ Mona's Herald. Wednesday, 11 November 1908 Page: 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "David also known as Dawsey Kewley". FamilySearch.

- 1 2 3 Mona's Herald. Wednesday, 29 October 1879 Page: 3

- ↑ The Manx Sun Saturday, 26 March 1904 Page: 8

- 1 2 3 'David 'Dawsey' Kewley memorial needs new home' Archived 12 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine on IOM Today, 12 February 2009 (accessed 25 November 2016)

- ↑ Isle of Man Times. Saturday, 10 June 1905 Page: 17

- ↑ Isle of Man Times. Saturday, 26 March 1904 Page: 10

- ↑ Mona's Herald. Saturday, 13 August 1870 Page: 6

- ↑ Mona's Herald. Saturday, 22 July 1871 Page: 7

- 1 2 3 Isle of Man Examiner. Saturday, 26 March 1904 Page: 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 Manx Sun. Saturday, 4 August 1888 Page: 13

- 1 2 Mona's Herald. Saturday, 4 August 1888 Page: 2

- ↑ Manx Sun. Saturday, 1 September 1888 Page: 4

- 1 2 Mona's Herald. Wednesday, 7 November 1888 Page: 4

- 1 2 3 4 Mona's Herald. Wednesday, 23 October 1878 Page: 4

- ↑ Manx Sun. Saturday, 26 October 1878 Page: 12

- ↑ Manx Sun. Saturday, 1 February 1879 Page: 12

- 1 2 3 Manx Sun.Saturday, 27 September 1879 Page: 13

- 1 2 3 Mona's Herald. Wednesday, 9 August 1882 Page: 5

- 1 2 3 4 Manx Sun. Saturday, 31 May 1884 Page: 4

- 1 2 3 4 5 Manx Sun. Saturday, 27 September 1884 Page: 12

- ↑ Isle of Man Times. Wednesday, 22 August 1888 Page: 6

- ↑ Manx Sun. Thursday, 10 August 1893 Page: 3

- ↑ Manx Sun Saturday 16 September 1893.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Isle of Man Times. Saturday, 2 April 1904 Page: 4

- 1 2 3 Manx Sun Saturday, 31 December 1904 Page: 5

- ↑ Isle of Man Times. Saturday, 25 March 1905 Page: 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Isle of Man Examiner. Saturday, 10 June 1905 Page: 4