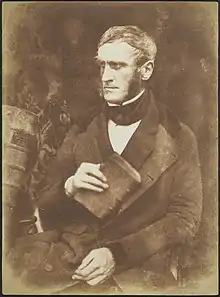

David Maitland Makgill Crichton | |

|---|---|

David Maitland Makgill Crichton from Disruption Worthies[1] | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 March 1801 |

| Died | 11 July 1851 |

David Maitland Makgill Crichton (4 March 1801 – 11 July 1851) was a Scottish lawyer who inherited his father's estate at Nether Rankeilour in Fife to become a country gentleman. He played an important role in the formation of the Free Church of Scotland and consequently was photographed by Hill & Adamson. He organised a local committee to start the Fife Sentinel newspaper. Following his death a memoir of his life was published, written by J. W. Taylor, a Free Church minister from Fife. His statue overlooks the South Bridge in Cupar.

Ancestry and early life

David Maitland Makgill Crichton, of Rankeilour, was born at Nether Rankeilour on 4 March 1801.[2] He was the fifth child and the second son of a family of fifteen.[3] His father, Colonel Maitland, was descended from the Lauderdale family.[2] His mother was Marie Johnstone of Lathrisk.[4] His grandfather was the Fredrick Lewis Maitland, son of Charles Maitland. His uncle, Frederick Maitland, was a very distinguished naval officer, who on board the Bellerophon received the submission of Napoleon. About the year 1837, David established his claim to become heir to the first Lord Frendraught,- a Scottish peer who owed his title to Charles I., and had been one of the officers of the Marquis of Montrose. It was in this way he took the name of Crichton in addition to Maitland, that of his father, and Makgill, that of his grandmother.[5] Through his grandmother, the Hon. Margaret Makgill of Rankeilour, the name of Crichton represents him as heir of line to Viscount Frendraught, Lord Crichton, whose daughter was the wife of Sir James Makgill of 1665.[2][6]

David was a pupil at St Andrews Grammar school and with the help of his tutor, Mr Ogilvie, proceeded to the University of St Andrews and subsequently the University of Edinburgh.[3]

As a younger son he studied for the bar, and passed as advocate in 1822. His professional practice as an advocate was short; for it was not in that direction that his energies were to be called out. It was in the great church questions of Scotland that the spirit and strength of the man were to be employed. His elder brother died, and he succeeded to the heritage of Rankeilour, whereby he secured the leisure of a country gentleman.[2]

Activities after his inheritance

He married Miss Hog of Newliston, and during their short wedded life he was impressed by those solemn views of sacred things which ever after moulded his character. His first wife died of tuberculosis on Madeira after a period of illness.[3] Scotland, under Thomas Chalmers, was entering upon one of those great religious revolutions which in every age have left their mark upon her national history. Maitland Makgill Crichton threw himself into the movement with all the zeal of an earnest man, and continued to the end of his life to devote all his powers to the cause. It was in this attitude that he was known to his countrymen. Zealous in church extension he was not less ardent in maintaining non-intrusion, and the spiritual independence of the Church.[2] Throughout Scotland he travelled, visiting every town, village, and almost every rural parish, and stirring the hearts of thousands by his powerful pleadings. It was in the interest of the same high principles that he contested in 1837 the representation of the St Andrews district of burghs in Parliament with Mr Edward Ellice and Mr Johnstone of Rennyhill. He lost the election only by the narrow majority of 29. Great principles have often unexpected issues. Maitland Makgill Crichton, when he was battling for the great principles of the Church of Scotland, never dreamed of that Church being broken up. But when the Church in the contest was led on step by step until she was brought up to the Disruption, Makgill Crichton was in the front ranks of those who recognised it as an inevitable event, and who set themselves to organise the Free Church of Scotland. To the service of this Church he devoted his thoughts and his efforts up to the period of his death. One of the last public services in which Makgill Crichton was engaged was the succouring of Dr Adam Thomson of Coldstream. Dr Thomson had laboured with effort, and embarked all his means to obtain a cheap-priced Bible for his countrymen. He succeeded in his enterprise, but it was at his own cost and pecuniary ruin.[2]

Other activities

He spontaneously discounted 12 per cent from all the rents when the corn-laws were abolished. He was successful as a rearer of stock, converted a large extent of whinny moor into arable land, and acted with his usual energy in the capacity of president of an agricultural society, a deputy-lieutenant and as a captain of yeomanry. He introduced a sweeping reform into the management of the road-trusts of Fife; lectured on British poetry to the Philosophical Association of Cupar; secured a bridge instead of a level crossing over the railway at that town; and obtained a reduction of the plough-gate rate in the county, for which the farmers presented him with a handsome dinner service, emblazoned with his crest.[7]

Death and legacy

At length the vigour of his constitution broke down under his many labours. The incessant strain had promoted complicated organic disease. At the age of fifty years, Makgill Crichton died at his own home somewhat suddenly, as he himself desired on 11 July 1851.

Shortly after his death, a memoir of Mr Crichton, prepared by the Rev. J. W. Taylor, of the Free Church, Flisk and Creich, was published by Constable.[2] Some years later, a statue in memory of Mr Crichton was erected in Cupar. It stands overlooking the Railway Bridge, which his energetic exertious forced reluctant Directors to erect in the place of a level crossing.[8]

Family

He married twice:

- Elanor Julian Hog of Newliston in 1827 (she died of TB on Madeira 5 years later, aged 31 leaving David the widowed father of four children)[9] and had issue-

- Charles Julian Maitland Makgill Crichton of Rankeilour, who was born on 15 May 1828. Charles married Anna Campbell Jarvis, on 24 December 1851, daughter of the late James R. Jarvis, Lieutenant, R. N., Colonial Secretary, and member of the Supreme Council for the island of Tobago; and dying 22 January 1858, left issue — David Maitland Makgill Crichton, Esq. of Rankeilour, a minor, born 24 March 1854 who became a major-general.[2]

- Esther, daughter of Andrew Coventry of Shanuile, Professor of Agriculture[2] on 2 December 1834.

References

Citations

- ↑ Wylie 1881.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Conolly 1866.

- 1 2 3 CofS mag 1853.

- ↑ Free CofS mag 1853, p. 437.

- ↑ Macphail 1854.

- ↑ Anderson 1877.

- ↑ Free CofS mag 1853, p. 441.

- ↑ Rogers 1872.

- ↑ Free CofS mag 1853.

Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Makgill of Rankellior". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 1. A. Fullarton & co. p. 727-703.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Brown, Thomas (1893). Annals of the disruption with extracts from the narratives of ministers who left the Scottish establishment in 1843 by Thomas Brown. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. pp. 61, et passim.

- Buchanan, Robert (1854). The ten years' conflict : being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 2. Glasgow ; Edinburgh ; London ; New York: Blackie and Son. pp. 248, et passim.

- Conolly, Matthew Forster (1866). Biographical dictionary of eminent men of Fife of past and present times : natives of the county, or connected with it by property, residence, office, marriage, or otherwise. Edinburgh: Inglis & Jack. pp. 134-135.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Guthrie, Thomas (1874). Autobiography of Thomas Guthrie, D.D., and memoir by his sons. Vol. 1. New York: R. Carter and brothers. pp. 210-213.

- Macphail (1854). "Review of Memoir of David Maitland Makgill Crichton of Nether Rankeilour". Macphail's Edinburgh ecclesiastical journal and literary review. Vol. 17–18. Edinburgh. pp. 31-46.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rogers, Charles (1872). Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland. Vol. 2. London: Published for the Grampian Club [by] C. Griffin. pp. 85-86.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Taylor, James William (1853). Memoir of the Late David Maitland Makgill Crichton of Nether Rankeilour. Edinburgh: T. Constable and Company.

- Wylie, James Aitken, ed. (1881). Disruption worthies : a memorial of 1843, with an historical sketch of the free church of Scotland from 1843 down to the present time. Edinburgh: T. C. Jack. pp. 185–192.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Review of Memoir of David Maitland Makgill Crichton of Nether Rankeilour". Church of Scotland magazine and review. Vol. 1. Church of Scotland. 1853. pp. 683-690.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "David Maitland Makgill Crichton of Nether Rankeilour". The Free Church Magazine. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Johnstone and Hunter. 1853. pp. 436-445.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.