The ministry of a deaconess is a usually non-ordained ministry for women in some Protestant, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Orthodox churches to provide pastoral care, especially for other women, and which may carry a limited liturgical role. The word comes from the Greek diakonos (διάκονος), for "deacon", which means a servant or helper and occurs frequently in the Christian New Testament of the Bible. Deaconesses trace their roots from the time of Jesus Christ through to the 13th century in the West. They existed from the early through the middle Byzantine periods in Constantinople and Jerusalem; the office may also have existed in Western European churches.[1] There is evidence to support the idea that the diaconate including women in the Byzantine Church of the early and middle Byzantine periods was recognized as one of the major non-ordained orders of clergy.[2]

The English separatists unsuccessfully sought to revive the office of deaconesses in the 1610s in their Amsterdam congregation. Later, a modern resurgence of the office began among Protestants in Germany in the 1840s and spread through Nordic States, Netherlands, United Kingdom and the United States. Lutherans were especially active and their contributions are seen in numerous hospitals. The modern movement reached a peak about 1910, then slowly declined as secularization undercut religiosity in Europe and the professionalization of nursing and social work offered other career opportunities for young women. Deaconesses continue to serve in Christian denominations such as Lutheranism and Methodism, among others.[3][4] Before they begin their ministry, they are consecrated as deaconesses.[5]

Non-clerical deaconesses should not be confused with women ordained deacons such as in the Anglican churches, the Methodist churches, and the Protestant Church in the Netherlands, many of which have both ordained deacons and consecrated deaconesses; in Methodism, the male equivalent to female deaconesses are Home Missioners.[6]

Early Christian period

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

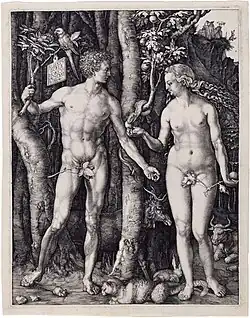

"Adam and Eve" by Albrecht Dürer (1504) |

The oldest reference to women as deaconesses occurs in Paul's letters (c. AD 55–58). Their ministry is mentioned by early Christian writers such as Clement of Alexandria[7] and Origen.[8] Secular evidence from the early 2nd century confirms this. In a letter Pliny the Younger attests to the role of the women deaconesses. Pliny refers to "two maid-servants" as deacons whom he tortures to find out more about the Christians. This establishes the existence of the office of the deaconesses in parts of the eastern Roman Empire from the earliest times. 4th-century Fathers of the Church, such as Epiphanius of Salamis,[9] Basil of Caesarea,[10] John Chrysostom[11] and Gregory of Nyssa[12] accept the ministry of deaconesses as a fact.

The Didascalia of the Apostles is the earliest document that specifically discusses the role of deacons and deaconesses more at length. It originated in Aramaic speaking Syria during the 3rd century, but soon spread in Greek and Latin versions. In it the author urges the bishop: "Appoint a woman for the ministry of women. For there are homes to which you cannot send a deacon to their women, on account of the heathen, but you may send a deaconess ... Also in many other matters the office of a deaconess is required."[13] The bishop should look on the man who is a deacon as Christ and the woman who is a deaconess as the Holy Spirit, denoting their prominent place in the church hierarchy.[14]

Deaconesses are also mentioned in Canon 19 of Niceae I which states that “since they have no imposition of hands, are to be numbered only among the laity”.[15] The Council of Chalcedon of 451 decreed that women should not be installed as deaconesses until they were 40 years old. The oldest ordination rite for deaconesses is found in the 5th-century Apostolic Constitutions.[16] It describes the laying on of hands on the woman by the bishop with the calling down of the Holy Spirit for the ministry of the diaconate. A full version of the rite, with rubrics and prayers, has been found in the Barberini Codex of 780 AD. This liturgical manual provides an ordination rite for women as deaconesses which is virtually identical to the ordination rite for men as deacons.[17] Other ancient manuscripts confirm the same rite.[18] However some scholars such as Philip Schaff have written that the ceremony performed for ordaining deaconesses was "merely a solemn dedication and blessing."[19] Still, a careful study of the rite has persuaded most modern scholars that the rite was fully a sacrament in present-day terms.[20]

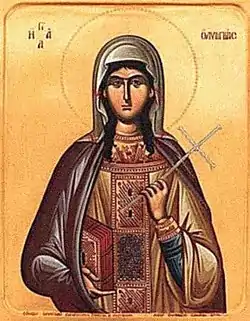

Olympias, one of the closest friends and supporters of the Archbishop of Constantinople John Chrysostom, was known as a wealthy and influential deaconess during the 5th century.[2][21] Justinian's legislation in the mid-6th century regarding clergy throughout his territories in the East and the West mentioned men and women as deacons in parallel. He also included women as deacons among those he regulated for service at the Great Church of Hagia Sophia, listing men and women as deacons together, and later specifying one hundred deacons who were men and forty who were women. Evidence of continuing liturgical and pastoral roles is provided by Constantine Porphyrogenitus' 10th-century manual of ceremonies (De Ceremoniis), which refers to a special area for deaconesses in Hagia Sophia.[2]

Pauline text

Paul's earliest mention of a woman as deacon is in his Letter to the Romans 16:1 (AD 58) where he says: "I commend to you our sister Phoebe, who is the servant of the church at Cenchreae". The original Greek says: οὖσαν διάκονον, ousan diakonon, being [the] [female] servant of the church at Cenchreae. The word "diakonon" means servant in nearly all of its 30 uses in the New Testament, but may also be used to refer to the church office of deacon. There is no scholarly consensus regarding whether the phrase here denotes "an official title of a permanent ministry." The term may refer to her serving in a more generic sense, without holding a church office. This is the primary meaning, and also how Paul uses the term elsewhere in the Letter to the Romans.[22]

A reference to the qualifications required of deacons appears in Paul's First Epistle to Timothy 3:8–13 (NRSV translation):

Deacons likewise must be serious, not double-tongued, not indulging in much wine, not greedy for money; they must hold fast to the mystery of the faith with a clear conscience. And let them first be tested; then, if they prove themselves blameless, let them serve as deacons. Women likewise must be serious, not slanderers, but temperate, faithful in all things. Let deacons be married only once, and let them manage their children and their households well; for those who serve well as deacons gain a good standing for themselves and great boldness in the faith that is in Christ Jesus.[14]

This verse about "the women" appears in the middle of a section that also addresses the men. However, the words regarding "the women" may refer to the wives of male deacons, or to deacons who are women. The transition from deacons generally to female deacons in particular may make sense linguistically, because the same word διακονοι covers both men and women. To indicate the women, the Greeks would sometimes say διάκονοι γυναῖκες ("deacon women"). This expression appears in the church legislation of Justinian.[23] This interpretation is followed by some early Greek Fathers such as John Chrysostom[24] and Theodore of Mopsuestia.[25] However, this is not the phrase used here, where Paul refers simply to γυναῖκας (women).

Commentary on 1 Corinthians 9:5 "Have we not the right to take a woman around with us as a sister, like all the other apostles?" by Clement of Alexandria (150 AD to 215 AD):

But the latter [the apostles], in accordance with their ministry [διακονια], devoted themselves to preaching without any distraction, and took women with them, not as wives, but as sisters, that they might be their co-ministers [συνδιακονους] in dealing with women in their homes. It was through them that the Lord's teaching penetrated also the women's quarters without any scandal being aroused. We also know the instructions about women deacons [διακονών γυναικών] which are given by the noble Paul in his other letter, the one to Timothy [1 Timothy 3:11].

— Stromata Book 3, chapter 6, 54, 3-4

As Clement of Alexandria made mention of Paul's reference to deaconesses in 1 Timothy 3:11, so Origen of Alexandria (184 AD to 254 AD) commented on Phoebe, the deacon that Paul mentions in Romans 16:1–2:

This text teaches with the authority of the Apostle that even women are instituted deacons in the Church. This is the function which was exercised in the church of Cenchreae by Phoebe, who was the object of high praise and recommendation by Paul… And thus this text teaches at the same time two things: that there are, as we have already said, women deacons in the Church, and that women, who by their good works deserve to be praised by the Apostle, ought to be accepted in the diaconate.

The Apostolic Constitutions say:

Concerning a deaconess, I, Bartholomew enjoin O Bishop, thou shalt lay thy hands upon her with all the Presbytery and the Deacons and the Deaconesses and thou shalt say: Eternal God, the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the creator of man and woman, that didst fill with the Spirit Mary and Deborah, and Anna and Huldah, that didst not disdain that thine only begotten Son should be born of a woman; Thou that in the tabernacle of witness and in the temple didst appoint women guardians of thy holy gates: Do thou now look on this thy handmaid, who is appointed unto the office of a Deaconess and grant unto her the Holy Spirit, and cleanse her from all pollution of the flesh and of the spirit, that she may worthily accomplish the work committed unto her, to thy glory and the praise of thy Christ.

Women as deacons

Two types of monastic women were typically ordained to the diaconate in the early and middle Byzantine period: abbesses and nuns with liturgical functions, as well as the wives of men who were being raised to the episcopacy. There was a strong association of deacons who were women with abbesses starting in the late fourth century or early fifth century in the East, and it occurred in the medieval period in the Latin as well as the Byzantine Church.[2] Principally, these women lived in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, where the office of deaconess was most often found.[14] There is literary evidence of a diaconate including women, particularly in Constantinople, and archaeological evidence of deaconesses in a number of other areas in the Empire, particularly Asia Minor.[2] One example of a woman from Constantinople being a deacon during the post-Constantine period was Olympias, a well-educated woman, who after being widowed devoted her life to the church and was ordained a deacon. She supported the church with gifts of land and her wealth which was typical during this period. Women who are deacons are often mistaken as being only widows or wives of deacons; and it is sometimes described that they came out of an order of widows. Minor church offices developed about the same time as the diaconate in response to the needs of growing churches. Widows, however, were elderly women of the congregation in need of economic help and social support due to their situation. This concept is mentioned in the first Acts 6:1 and 9:39–41 and 1 Timothy 5. These widows had no specific duties compared to that of the deacons. In the Apostolic Constitutions women who were deacons were recognized as having power over the widows in the church. The widows were cautioned to obey "women deacons with piety, reverence and fear".[14] In the first four centuries of the church, widows were recognized members of the church who shared some similar functions of a deaconess; yet did not share the same responsibilities or importance.

Roles

In the Byzantine church women who were deacons had both liturgical and pastoral functions within the church.[2] These women also ministered to other women in a variety of ways, including instructing catechumens, assisting with women's baptisms and welcoming women into the church services.[26] They also mediated between members of the church, and they cared for the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of the imprisoned and the persecuted.[27] They were sent to women who were housebound due to illness or childbirth. They performed the important sacramental duty of conducting the physical anointing and baptism of women. Ordination to the diaconate was also appropriate for those responsible for the women's choir, a liturgical duty. Evidence in the Vita Sanctae Macrinae (or Life of St. Macrina) shows that Lampadia was responsible for the women's choir. Some believe that they were also officiant of the Eucharist, but this practice was seen as invalid.[28]

Art

It has been argued that some examples of Christian art reflect the leadership roles of women as deacons including administration of the host, teaching, baptizing, caring for the physical needs of the congregation and leading the congregation in prayers.[29] Some depictions of women in early Christian art in various ministerial roles were, arguably, later covered up to depict men. The fresco in the Catacombs of Priscilla has been claimed as one example of a conspiracy to deny women's involvement in the Eucharist.[27] Another example involves the chapel of St. Zeno in the Church of St. Praxida in Rome. An inscription denoting a woman in the mosaic as, "Episcopa Theodora" was altered by dropping the feminine –ra ending, thereby transforming into a masculine name. Because episcopa is the feminine form of the Greek word for bishop or overseer, the inscription suggests that Theodora was a woman who became a bishop; however, this appellation was also originally used to honour the mother or wife of a bishop.[29]

Decline of the diaconate including women

After the 4th century the role of women as deacons changed somewhat in the West. It appeared that the amount of involvement with the community and the focus on individual spirituality[28] did not allow any deacon who was a woman to define her own office. During the rule of Constantine, as Christianity became more institutionalized, leadership roles for women decreased.[14] It was during the fifth and sixth centuries in the western part of the Roman Empire that the role of deaconesses became less favorable. The councils of Orange in 441 and Orléans in 533 directly targeted the role of the deaconesses, forbidding their ordination. By at least the 9th or 10th century, nuns were the only women ordained as deacons. Evidence of diaconal ordination of women in the West is less conclusive from the 9th to the early 12th centuries than for previous eras, although it does exist and certain ceremonials were retained in liturgy books to modern times.

In Constantinople and Jerusalem, there is enough of a historical record to indicate that the diaconate including women continued to exist as an ordained order for most if not all of this period. In the Byzantine Church, the decline of the diaconate which included women began sometime during the iconoclastic period with the vanishing of the ordained order for women in the twelfth century. It is probable the decline started in the late seventh century with the introduction into the Byzantine Church of severe liturgical restrictions on menstruating women. By the eleventh century, the Byzantine Church had developed a theology of ritual impurity associated with menstruation and childbirth. Dionysius of Alexandria and his later successor, Timothy, had similar restriction on women receiving the Eucharist or entering the church during menses. Thus, "the impurity of their menstrual periods dictated their separation from the divine and holy sanctuary."[2] By the end of the medieval period the role of the deacons decreased into mere preparation for priesthood, with only liturgical roles. In the 12th and 13th century, deaconesses had mainly disappeared in the European Christian church and, by the 11th century, were diminishing in the Eastern Mediterranean Christian churches.[14] Even so, there is substantial evidence of their existence throughout the history of Eastern Churches.[30]

Restoration of the female diaconate

In August 2016, the Catholic Church established a Study Commission on the Women's Diaconate to study the history of female deacons and to study the possibility of ordaining women as deacons.[31] Until today, the Armenian Apostolic Church is still ordaining religious Sisters as deaconesses, the last Monastic deaconess was Sister Hripsime Sasounian (died in 2007) and on 25 September 2017, Ani-Kristi Manvelian a twenty-four-year-old woman was ordained in Tehran's St. Sarkis Mother Church as the first lay deaconess after many centuries.[32] The Russian Orthodox Church had a female monastic subdiaconate into the 20th century. The Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece restored the female monastic order of "deaconess" in 2004.[33] And on 16 November 2016, the Holy Synod of Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria also restored the female diaconate, actually for subdeaconesses.[34]

Reformation era

The Damsels of Charity, founded in 1559 by Prince Henri Robert de la Marck of Sedan, have sometimes been regarded as the first Protestant association of deaconesses, although they were not called by that name.[35]

Mennonites had a practice of consecrating deaconesses.[35] Count Zinzendorf of the Moravian Church began consecrating deaconesses in 1745.[36][37]

Late modern period

The deaconess movement was revived in the mid 19th century, starting in Germany and spread to some other areas, especially among Lutherans, Anglicans and Methodists. The professionalization of roles such as nursing and social work in the early 20th century undercut its mission of using lightly trained amateurs. By the late 20th century secularization in Europe had weakened all church-affiliated women's groups,[38] though deaconesses continue to play an important role in many Christian denominations today.[3][4]

Europe

The spiritual revival in the Americas and Europe of the 19th century allowed middle-class women to seek new roles for themselves; they now could turn to deaconess service. In Victorian England, and northern Europe, the role of deaconess was socially acceptable. A point of internal controversy was whether that the lifelong vow prevented the deaconesses from marrying. While deacons are ordained, deaconesses are not.

The modern movement began in Germany in 1836 when Theodor Fliedner and his wife Friederike Münster opened the first deaconess motherhouse in Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, inspired by the existing deaconesses among the Mennonites.[35] The diaconate was soon brought to England[39] and Scandinavia, Kaiserswerth model. The women obligated themselves for five years of service, receiving room, board, uniforms, pocket money, and lifelong care. The uniform was the usual dress of the married woman. There were variations, such as an emphasis on preparing women for marriage through training in nursing, child care, social work and housework. In the Anglican churches, the diaconate was an auxiliary to the ordained ministry. By 1890 there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Europe, chiefly in Germany, Scandinavia and England. [40]

In Switzerland, the "Institution des diaconesses" was founded in 1842 in Échallens by the Reformed pastor Louis Germond.[41][42] In France an order of Protestant deaconesses named "Diaconesses de Reuilly" were founded in 1841 in Paris by Reformed pastor Antoine Vermeil and by a parishioner named Caroline Malvesin.[43] In Strasbourg another order was founded in 1842 by Lutheran minister François-Henri Haerter (a.k.a. Franz Heinrich Härter in German). All three deaconesses orders are still active today, especially in hospitals, old age care and spiritual activities (retreats, teaching and preaching).

In World War II, diaconates in war zones sustained heavy damage. As eastern Europe fell to communism, most diaconates were shut down and 7000 deaconesses became refugees in West Germany.

The DIAKONIA World Federation was established in 1947 with motherhouses from Denmark, Finland, France, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland signed the constitution.[44] By 1957, in Germany there were 46,000 deaconesses and 10,000 associates. Other countries reported a total of 14,000 deaconesses, most of them Lutherans. In the United States and Canada, 1,550 women were counted, half of them in the Methodist churches.[45]

Denmark

Charged by Princess Louise to investigate the Deaconess Institutes in Germany, Sweden and France with a view to creating one in Denmark, Louise Conring was the first Danish woman to be trained in nursing, ultimately heading the Deaconess Institute in Copenhagen from its inauguration in 1863.[46][47]

England and the British Empire

In 1862, Elizabeth Catherine Ferard received Deaconess Licence No. 1 from the Bishop of London, making her the first deaconess of the Church of England.[48] On 30 November 1861 she had founded the North London Deaconess Institution and the community which would become the (deaconess) Community of St. Andrew. The London Diocesan Deaconess Institution also trained deaconesses for other dioceses and some served overseas and began deaconess work in Melbourne, Lahore, Grahamstown, South Africa and New Zealand. In 1887, Isabella Gilmore oversaw the revival of deaconesses not living in a community.[49]

Lady Grisell Baillie (1822–1891) became the first deaconess in the Church of Scotland in 1888. She was commemorated in 1894 by the opening of the Lady Grisell Baillie Memorial Hospital in Edinburgh which was later renamed the Deaconess Hospital.[50]

Finland

In the 1850s, Amanda Cajander trained as a deaconess at the Evangelical Deaconess Institute in Saint Petersburg.[51] The wealthy Finnish philanthropist Aurora Karamsin was familiar with the Russian institute, and when she decided to open a deaconess institution in Finland in Helsinki, she invited Cajander to be its first principal.[52] The institute opened in December 1867,[53] during the great Famine of 1866–68. The first deaconess to have been trained in Finland was Cecilia Blomqvist.

Norway

In 1866 Cathinka Guldberg went to Kaiserswerth, (Germany) to educate herself as a nurse and deaconess. She visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein, where she observed Pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working with the sick and the deprived. In 1869 she returned to Norway and established the first deaconess instuition in Norway, the Christiania Deaconess House (Diakonissehuset Christiania) and started Norway's first professional nursing program. [54][55][56]

Sweden

The first Deaconess institution in Sweden, Ersta diakoni, was founded in the capital of Stockholm in 1851. The office of head of the institution was offered to Maria Cederschiöld before it was founded, and Cederschiöld studied the deaconess institution Kaiserswerth in Germany under Theodor Fliedner in 1850-1851 before participating in the foundation of the institution in Sweden upon her return, herself becoming the first Swedish deaconess.[57] Maria Cederschiöld of the Ersta diakoni also participated in the foundation of the first deaconess institution in Norway in Oslo.[58]

North America

Lutheran pastor William Passavant was involved in many innovative programs; he brought the first four deaconesses to the United States after a visit to Fliedner in Kaiserswerth. They worked in the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).[59] Another more indirect product of Kaiserswerth was Elizabeth Fedde, who trained in Norway under a Kaiserswerth alumna, then established hospitals in Brooklyn, New York and Minneapolis, Minnesota (as well as provided the impetus for other hospitals in Chicago, Illinois and Grand Forks, North Dakota), although she turned down Passavant's invitation to administer his hospital.

In 1884, Germans in Philadelphia brought seven sisters from Germany to run their hospital. Other deaconesses soon followed and began ministries in several United States cities with large Lutheran populations. In 1895, the Lutheran General Synod approved an order of deaconesses, defining a deaconess as an "unmarried woman" of "approved fitness" serving "Christ and the Church". It set up its deaconess training program in Baltimore.[60] By the 1963 formation of the Lutheran Church in America, there were three main centers for deaconess work: Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Omaha. These three sisterhoods combined and form what became the Deaconess Community of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). Since 2019, the ELCA has permitted deaconesses (and deacons) to be ordained into its Word and Service roster.[61][62] The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS) has also promoted the role of deaconess.[63]

The imperatives of the Social Gospel movement (1880s–1920s) led deaconesses to improve life for the new immigrants in large cities.[64] In accord with the reform impulses of the Progressive Era, many agitated for laws protecting women workers, the establishment of public health and sanitation services, and improvement of social and state support for poor mothers and their children.[65][66] Beginning in 1889, Emily Malbone Morgan used the proceeds of her published writings to establish facilities where working woman and their children of all faiths could vacation and renew their spirits.

In 1888, Cincinnati's German Protestants opened a hospital ("Krankenhaus") staffed by deaconesses. It evolved into the city's first general hospital, and included a nurses' training school. It was renamed Deaconess Hospital in 1917. Many other cities developed a deaconess hospital in similar fashion.[67]

In Chicago, physician and educator Lucy Rider Meyer initiated deaconess training at her Chicago Training School for Home and Foreign Missions as well as editing a periodical, The Deaconess Advocate, and writing a history of deaconesses, Deaconesses: Biblical, Early Church, European, American (1889). She is credited with reviving the office of deaconess in the American Methodist Episcopal Church.[68]

In 1896 Methodist deaconesses founded the New England Deaconess Hospital to care for Bostonians, and the hospital added a staff of medical professionals in 1922. In 1996, the hospital merged with Beth Israel Hospital, which had opened in 1916 to serve Jewish immigrants, and thus formed the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

In 1907 Anna Alexander became the first (and only, due to the later suspension of deaconess as an office distinct from deacon)[69] African-American deaconess in the Episcopal Church.[70] She served in the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia during her entire career.[71]

Mennonites founded the Bethel Deaconess Home and Hospital Society for nursing education and service in Newton, Kansas, in 1908. Over the next half century, 66 Mennonite women served there. They were unmarried but did not take explicit vows of chastity and poverty. They worked and prayed under the close supervision of founder and head sister, Frieda Kaufman (1883–1944). With the growing professionalization of graduate nursing, few women joined after 1930.[72]

Canadian Methodists considered establishing a deaconess order at the general conference of 1890. They voted to allow the regional conferences to begin deaconess work, and by the next national conference in 1894, the order became national.[73] The Methodist National Training School and Presbyterian Deaconess and Missionary Training Home joined to become the United Church Training School in 1926, later joining with the Anglican Women Training College to become the Centre for Christian Studies, currently in Winnipeg.[74] This school continues to educate men and women for diaconal ministry in the United and Anglican churches.

Between 1880 and 1915, 62 training schools were opened in the United States. The lack of training had weakened Passavant's programs. However recruiting became increasingly difficult after 1910 as young women preferred graduate nursing schools or the social work curriculum offered by state universities.[75]

Federated States of Micronesia

In 1982, Adelyn Noda became the youngest woman in Kosrae, the Federated States of Micronesia, to be ordained as a deaconess.[76][77] She went on to become a teacher.

Australia

The Presbyterian and Methodist Churches both had deaconesses prior to church union that formed the Uniting Church in Australia in 1977. In 1991, the National Assembly agreed to ordain deacons — men and women. The first person to be ordained as a deacon was Betty Matthews in Perth, Western Australia, in 1992. The member association is Diakonia of the Uniting Church in Australia (DUCA).[78]

The Anglican Church in Australia ordains transitional deacons and permanent deacons. The professional organisation for permanent deacons is the Australian Anglican Diaconal Association.[79]

New Zealand

The Presbyterian Church of New Zealand (now the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand) started a Deaconess order in 1903 with the establishment of the Deaconess Training House in Dunedin. The work of deaconesses in New Zealand had been begun by Sister Christabel Duncan who arrived from Australia to begin work in Dunedin in 1901.[80] By 1947 Deaconesses could choose from two three-year courses – the General Course or the Advanced Course. Women undertaking the Advanced Course could gain a Bachelor of Divinity Degree with the same theological training as Ministers through the Theological Hall at Knox College in Dunedin, as well as training in social services, teaching, nursing and missionary service. In 1965 the Church allowed women to be ordained as ministers leading to a decline in women seeking deaconess training and the Deaconess Order was wound up in 1975. Deaconesses could either become ordained as Ministers or become lay members of the Church, while still remaining employed.

The Presbyterian Research Centre, Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand in Dunedin, New Zealand, holds a collection of papers and other memorabilia relating to Presbyterian Deaconesses. The PCANZ Deaconess Collection was added to the UNESCO Memory of the World New Zealand Register[81] in 2018.

Philippines

There are four member associations of the DIAKONIA World Federation in the Philippines: Commission on Deaconess Service of the United Methodist Church; Deaconess Association of Iglesia Evangelica En Las Islas Filipinas; Deaconess Association of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines; and Ang Iglesia Metodista sa Pilipinas.[82]

The Iglesia ni Cristo's deaconesses are married women.

See also

References

- ↑ Macy, Gary (2007). The Hidden History of Women's Ordination: Female Clergy in the West. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Karras, Valerie A. (June 2004). "Female Deacons in the Byzantine Church". Church History. 73 (2): 272–316. doi:10.1017/S000964070010928X. ISSN 0009-6407. S2CID 161817885.

- 1 2 Zagore, Robert. "Deaconess Ministry". Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- 1 2 Brooks, Alexander; Hunter, Louis Sr. "For Deaconesses". Columbus Avenue African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

- ↑ Naumann, Cheryl D. (2009). In the Footsteps of Phoebe: A Complete History of the Deaconess Movement in the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Concordia Publishing House. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-7586-0831-4.

- ↑ "Deaconess & Home Missioner Ministry". United Methodist Women. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ Commentary on 1 Corinthians 9:5, Stromata 3,6,53.3-4.

- ↑ Commentary on Romans 10:17; Migne PG XIV col. 1278 A–C.

- ↑ Migne PG 42, cols 744–745 & 824–825

- ↑ I. Defarrari (ed.), Saint Basil: the Letters, London 1930, Letter 199.

- ↑ Migne PG 62, col. 553.

- ↑ Migne PL 46, cols 988–990.

- ↑ Didascalia 16 § 1; G. Homer, The Didascalia Apostolorum, London 1929; http://www.womenpriests.org/minwest/didascalia.asp Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Olsen, Jeannine E. (1992). One ministry many roles: deacons and deaconesses through the centuries. Concordia scholarship today. St Louis: Concordia Publishing House. pp. 22, 25, 27, 29, 41, 53, 58, 60, 70. ISBN 978-0-570-04596-0.

- ↑ "Canons of the Council of Nicea". Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ↑ Apostolic Constitutions VIII, 19-20; F. X. Funk, Didascalia et Constitutiones Apostolorum, Paderborn 1905, 1:530.

- ↑ "The Ordination of Women Deacons/ Barberini gr. 336". Womenpriests.org. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ Many texts are now online: "Grottaferrata GR Gb1 (1020 AD)". womenpriests.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.; "Vatican GR 1872 (1050 AD)". womenpriests.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.; and "Coislin GR 213 (1050 AD)". womenpriests.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ↑ "Excursus on the Deaconess of the Early Church". ccel.org. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ↑ R. Gryson, The Ministry of Women in the Early Church, Collegeville 1976; originally Le ministère des femmes dans l'Église ancienne, Gembloux 1972, esp. pp. 117–118; Y. Congar, 'Gutachten zum Diakonat der Frau', Amtliche Mitteilungen der Gemeinsamen Synode der Bistümer der Bundesrepublik Deutschlands, Munich 1973, no 7, p. 37–41; C. Vaggagini, 'L'Ordinazione delle diaconesse nella tradizione greca e bizantina', Orientalia Christiana Periodica 40 (1974) 145–189 ; H. Frohnhofen, 'Weibliche Diakone in der frühen Kirche', Studien zur Zeit 204 (1986) 269–278; M-J. Aubert, Des Femmes Diacres. Un nouveau chemin pour l'Église, Paris 1987, esp. p. 105; D. Ansorge, 'Der Diakonat der Frau. Zum gegenwärtigen Forschungsstand', in T.Berger/A.Gerhards (ed.), Liturgie und Frauenfrage, St. Odilien 1990, pp. 46–47; A. Thiermeyer, 'Der Diakonat der Frau', Theologisch Quartalschrift 173 (1993) 3, 226–236; also in Frauenordination, W. Gross (ed.), Munich 1966, pp. 53–63; Ch. Böttigheimer, , 'Der Diakonat der Frau', Münchener Theologische Zeitschrift 47 (1996) 3, 253–266; P. Hofrichter, 'Diakonat und Frauen im kirchlichen Amt', Heiliger Dienst 50 (1996) 3, 140–158; P. Hünermann, 'Theologische Argumente für die Diakonatsweihe van Frauen', in Diakonat. Ein Amt für Frauen in der Kirche – Ein frauengerechtes Amt?, Ostfildern 1997, pp. 98–128, esp. p. 104; A. Jensen, 'Das Amt der Diakonin in der kirchlichen Tradition der ersten Jahrtausend', in Diakonat. Ein Amt für Frauen in der Kirche – Ein frauengerechtes Amt?, Ostfildern 1997, pp. 33–52, esp. p. 59; D. Reininger, Diakonat der Frau in der einen Kirche, Ostfildern 1999 pp. 97–98; P. Zagano, Holy Saturday. An Argument for the Restoration of the Female Diaconate in the Catholic Church, New York 2000; J. Wijngaards, Women Deacons in the Early Church, New York 2002, pp. 99–107.

- ↑ "From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 9. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight".

- ↑ H. Schlier, Der Römerbrief, Freiburg 1977, pp. 440–441 (full discussion); same view in the commentaries by Th. Zahn, Der Brief des Paulus an die Römer, Leipzig 1925; E. Kühl, Der Brief des Paulus an die Römer, Leipzig 1913; M.J. Lagrange, Saint Paul, Épître aux Romains, Paris 1950; F. J. Leenhardt, L'Épître de saint Paul aux Romains, Neuchâtel 1957; H.W.Schmidt, Der Brief des Paulus an die Römer, Berlin 1962; O. Michel, Der Brief an die Römer, Göttingen 1963; E. Käsemann, An die Römer, Tübingen 1974. Major article: G. Lohfink, "Weibliche Diakone im Neuen Testament", in Die Frau im Urchristentum, ed. G. Dautzenberg, Freiburg 1983, pp. 320–338.

- ↑ Novella 6. 6 par. 1–10; 131. 23; 123.30, etc.; R. Schoell and G. Kroll, eds. Corpus iuris civilis, vol. III, Berlin 1899, pp. 43–45, 616, 662.

- ↑ Homily 11,1 On the First Letter to Timothy; Migne, PG 63, col. 553.

- ↑ In Epistolas b. Pauli Commentarii, ed. H. B. Swete, Cambridge 1882, vol. II, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Wharton, Annabel (1987). "Ritual and Reconstructed Meaning: The Neonian Baptistery in Ravenna". Art Bulletin. 69 (3): 358–375. doi:10.2307/3051060. JSTOR 3051060.

- 1 2 Grenz, Stanley J.; Kjesbo, Denise Muir (1995). Women in the church : a biblical theology of women in ministry. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8308-1862-4.

- 1 2 Swan, Laura (2001). The forgotten desert mothers : sayings, lives, and stories of early Christian women. New York: Paulist Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8091-4016-9.

- 1 2 Torjesen, Karen Jo (1993). When women were priests : women's leadership in the early church and the scandal of their subordination in the rise of Christianity. San Francisco: Harper. pp. 10, 16. ISBN 978-0-06-068661-1.

- ↑ "Ordination of Women to the Diaconate in the Eastern Churches: Essays by Cipriano Vagaggini: Edited by Phyllis Zagano: 9780814683101: Litpress.org : Paperback". Litpress.org. 27 December 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Francis institutes commission to study female deacons, appointing gender-balanced membership". ncronline.org. 2 August 2016. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ Tchilingirian, Hratch (16 January 2018). "Historic Ordination: Tehran Prelacy of the Armenian Church Ordains Deaconess". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ↑ url="Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "-- [ Greek Orthodox ] --". www.patriarchateofalexandria.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 Bancroft, J.M. (1890). Deaconesses in Europe: And Their Lessons for America. Women and the church in America. Hunt & Eaton. p. 44. ISBN 9780837014340. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ↑ Golder, C. (1903). History of the deaconess movement in the Christian church. Jennings and Pye. p. 106. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ↑ Hammond, Geordan (2009). "Versions of Primitive Christianity: John Wesley's Relations with the Moravians in Georgia, 1735-1737". Journal of Moravian History. Penn State University Press (6): 31–60. doi:10.2307/41179847. JSTOR 41179847. S2CID 248825006.

- ↑ Pat Thane; Esther Breitenbach (2010). Women and Citizenship in Britain and Ireland in the 20th Century: What Difference Did the Vote Make?. Continuum International. p. 70. ISBN 9780826437495.

- ↑ See Czolkoss, Michael: „Ich sehe da manches, was dem Erfolg der Diakonissensache in England schaden könnte“ – English Ladies und die Kaiserswerther Mutterhausdiakonie im 19. Jahrhundert. In: Thomas K. Kuhn, Veronika Albrecht-Birkner (eds.): Zwischen Aufklärung und Moderne. Erweckungsbewegungen als historiographische Herausforderung (= Religion - Kultur - Gesellschaft. Studien zur Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte des Christentums in Neuzeit und Moderne, 5). Münster 2017, pp. 255-280.

- ↑ Sister Mildred Winter, "Deaconess", in Julius Bodensieck, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Lutheran Church (Minneapolis: 1965) 659–64

- ↑ Biography of Louis GermondDeaconess in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ "Bienvenue à Saint-Loup" (in French). Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ "Adolphe Monod and Caroline Malvesin". www.monodgraphies.eu. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "DIAKONIA History Milestones". DIAKONIA World Federation. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ↑ Winter, "Deaconess", in Julius Bodensieck, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Lutheran Church p. 662.

- ↑ "Louise Conring". Den Store Danske (in Danish). Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Hilden, Adda (2003). "Louise Conring (1824 - 1891)" (in Danish). Kvinfo. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Deacons – Famous Deacons". DACE.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ↑ Henrietta Blackmore (2007). The beginning of women's ministry: the revival of the deaconess in the nineteenth-century Church of England. Boydell Press. p. 131. ISBN 9781843833086.

- ↑ "Scotland's First Deaconess", by D. P. Thompson, A. Walker & Son Ltd, Galashiels 1946.

- ↑ Janfelt, M. (1999). Den privat-offentliga gränsen: Det sociala arbetets strategier och aktörer i Norden 1860–1940. Nord (in Swedish). Nordisk Ministerråd. p. 177. ISBN 978-92-893-0300-2. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ↑ Markkola, Pirjo (2011). "Women's Spirituality, Lived Religion, and Social Reform in Finland, 1860–1920" (PDF). Perichoresis – the Theological Journal of Emanuel University. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ Marjomaa, Ulpu (2000). 100 Faces from Finland: A Biographical Kaleidoscope. FLS. p. 198. ISBN 951-746-215-8.

- ↑ Diakinissehusets første hundre år, Nils Bloch-Hoell, Diakonissehuset i Oslo 1968

- ↑ "Vår historie". Lovisenberg diakonale høgskole. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Trond Indahl. "Henrik Thrap-Meyer". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Elisabeth Christiansson: "Först och framför allt själen" Diakonins tankevärld omkring år 1850. Sköndalsinstitutet 2003

- ↑ Elisabeth Christiansson: "Först och framför allt själen" Diakonins tankevärld omkring år 1850. Sköndalsinstitutet 2003

- ↑ Christ Lutheran Church of Baden "Olde Economie Financial Group". Archived from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ↑ Frederick S. Weiser, "The Origins of Lutheran Deaconesses in America", Lutheran Quarterly (1999) 13#4 pp. 423–434.

- ↑ "Ordination to the Ministry of Word and Service" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ "Rostered Ministers of the ELCA". ELCA.org. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ Cheryl D. Naumann, In the Footsteps of Phoebe: A Complete History of the Deaconess Movement in the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (2009)

- ↑ Laceye Warner, "'Toward The Light': Methodist Episcopal Deaconess Work Among Immigrant Populations, 1885–1910", Methodist History (2005) 43#3 pp. 169–182.

- ↑ Rosemary Skinner Keller, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana U.P. p. 828. ISBN 978-0253346872.

- ↑ Pamela E. Klassen (2011). Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity. U. of California Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780520950443.

- ↑ Ellen Corwin Cangi, "Krankenhaus, Culture and Community: The Deaconess Hospital of Cincinnati, Ohio, 1888–1920", Queen City Heritage (1990) 48#2 pp. 3–14.

- ↑ "Lucy Rider Meyer". United Methodist Church General Commission on Archives and History website. Accessed 20 April 2016.

- ↑ Jan McM. Saltzgaber. "Deaconess Alexander - Biography".

- ↑ "Anna Alexander". Satucket.com. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Anna Alexander". Satucket.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Rachael Waltner Goossen, "Piety and Professionalism: The Bethel Deaconesses of the Great Plains", Mennonite Life (1994) 49#1 pp. 4–11.

- ↑ Whitely, Marilyn Fardig. Canadian Methodist Women, 1766–1925, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, pp. 184–185

- ↑ Griffith, Gwyn. Weaving a Changing Tapestry. 2009

- ↑ Cynthia A. Jurisson, "The Deaconess Movement", in Rosemary Skinner Keller et al., eds. Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America (Indiana U.P., 2006). pp. 828–9. online

- ↑ Buck, Elden M. (2005). Island of Angels: The Growth of the Church on Kosrae: Kapkapak Lun Church Fin Acn Kosrae, 1852-2002. Watermark Pub. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-9753740-6-1.

- ↑ Simon-McWilliams, Ethel (1987). Glimpses into Pacific Lives: Some Outstanding Women (Revised) (PDF). Portland, Oregon: Northwest Regional Educational Lab. pp. 52–3. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ "Diakonia UCA". Diakonia UCA. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ↑ "Australian Anglican Diaconal Association". Australian Anglican Diaconal Association. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ↑ Salmond, J. D. (1962), By love serve: The story of the order of deaconesses of the Presbyterian Church of New Zealand, Presbyterian Book Room, Christchurch

- ↑ "Archived copy". www.unescomow.org.nz. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Member Associations of DIAKONIA". DIAKONIA World Federation. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

Bibliography

- Church of England. The ministry of women, 1920, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Macmillan

- Diaconal Association of the Church of England. The Beginnings of Women's Ministry: The Revival of the Deaconess in the Church of England, edited by Henrietta Blackmore (Church of England Record Society, 2007) See online

- De Swarte Gifford, Carolyn. The American Deaconess movement in the early twentieth century, 1987. Garland Pub., ISBN 0-8240-0650-X

- Dougherty, Ian. Pulpit radical : the story of New Zealand social campaigner Rutherford , Saddle Hill Press, 2018.

- Gvosdev, Ellen. The female diaconate: an historical perspective (Light and Life, 1991)ISBN 0-937032-80-8

- Ingersol, S. (n.d.). The deaconess in Nazarene history. Herald of Holiness, 36.

- Jurisson, Cynthia A. "The Deaconess Movement" in Rosemary Skinner Keller et al., eds. Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America (Indiana U.P., 2006). pp. 821–33 online

- Martimort, Aime G., Deaconesses: An Historical Study (Ignatius Press, 1986).

- Salmond, James David. By love serve: the story of the Order of Deaconesses of the Presbyterian Church of New Zealand, 1962. Presbyterian Bookroom

- Webber, Brenda, and Beatrice Fernande. The Joy of service: life stories of racial and ethnic minority deaconesses and home missionaries (General Board of Global Ministries, 1992).

- Wijngaards, John. Women Deacons in the Early Church (Herder & Herder, 2002).

In other languages

- Diakonissen-Anstalt Kaiserswerth.Vierzehnter Bericht über die Diakonissen-Stationen am Libanon: namentlich über das Waisenhaus Zoar in Beirut, vom 1. Juli 1885 bis 30. Juni 1887. 1887. Verlag der Diakonissen-Anstalt,

- Herfarth, Margit. Leben in zwei Welten. Die amerikanische Diakonissenbewegung und ihre deutschen Wurzeln. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2014

- Lauterer, Heide-Marie. Liebestätigkeit für die Volksgemeinschaft: der Kaiserwerther Verband deutscher Diakonissenmutterhäuser in den ersten Jahren des NS-Regimes, 1994. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 3-525-55722-1

- Markkola, Pirjo. Synti ja siveys: naiset, uskonto ja sosiaalinen työ Suomessa 1860–1920 ["Sin and chastity: women, religion and social work in Finland 1860–1920"] (2002, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura), ISBN 951-746-388-X

External links

- Anglican Deaconess Association

- Concordia Deaconess Conference

- Lutheran Deaconess Association

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- DIAKONIA World Federation

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

- Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod Deaconesses

- Methodist Diaconal Order of the Methodist Church of Great Britain

- United Methodist Church

- Presbyterian Church in Canada

- Reformed Episcopal Church Order of Deaconesses

- United Church of Christ

- Grant Her Your Spirit – National Catholic Weekly

- The Deaconess and Church Training School: Paper Read at the Woman's Auxiliary Meeting of the Missionary Council at Washington, by Deaconess Susan Trevor Knapp (1903)

- The Deaconesses of the Church in Modern Times, compiled by Lawson Carter Rich (1907)

- Mary Amanda Bechtler: Deaconess of St. Mary's Chapel, St. John's Parish, Washington, D.C., by Oscar Lieber Mitchell (c. 1918)

- Deaconess Gilmore: Memories Collected by Deaconess Elizabeth Robinson (1924)

- Online full text of "The Ministry of Deaconesses" by Cecilia Robinson (1898)

- The beginning of women's ministry By Henrietta Blackmore

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 878.