| Jack the Ripper letters |

|---|

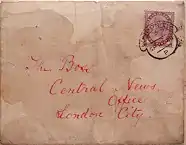

The "Dear Boss" letter was a message allegedly written by the notorious unidentified Victorian serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. Addressed to the Central News Agency of London and dated 25 September 1888, the letter was postmarked and received by the Central News Agency on 27 September. The letter itself was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September.[1]

Although many dispute its authenticity,[2] the "Dear Boss" letter is regarded as the first piece of correspondence signed by one Jack the Ripper, ultimately resulting in the unidentified killer being known by this name.[3]

Content

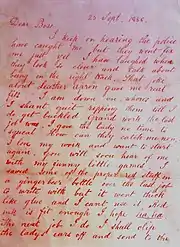

The "Dear Boss" letter was written in red ink, was two pages long and contains several spelling and punctuation errors. The overall motivation of the author was evidently to mock investigative efforts and to allude to future murders.[4] The letter itself reads:

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn't you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife's so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck. Yours truly

Jack the RipperDont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I'm a doctor now. ha ha[5]

Media publication

Initially, the letter was considered to be just one of many hoax letters purporting to be from the murderer.[6] However, following the discovery of the body of Catherine Eddowes in Mitre Square on 30 September, investigators noted a section of the auricle and earlobe of her right ear had been severed,[7] giving credence to the author's promise within the letter to "clip the lady's ears off". In response, the Metropolitan Police published numerous handbills containing duplicates of both this letter and the "Saucy Jacky" postcard in the hope that a member of the public would recognise the handwriting of the author.[n 1] Numerous local and national newspapers also reprinted the text of the "Dear Boss" letter in whole or in part. These efforts failed to generate any significant leads.[10]

Perpetrator pseudonym

Following the publication of the "Dear Boss" letter and the "Saucy Jacky" postcard, both forms of correspondence gained worldwide notoriety. These publications were the first occasion in which the name "Jack the Ripper" had been used to refer to the killer. The term captured the imagination of the public. In the weeks following their publication, hundreds of hoax letters claiming to be from "Jack the Ripper" were received by police and press alike, most of which copied key phrases from these letters.[3]

Authenticity

In the years following the Ripper murders, police officials stated that they believed both the "Dear Boss" letter and the "Saucy Jacky" postcard were elaborate hoaxes most likely penned by a local journalist.[n 2] Initially, these suspicions received little publicity, with the public believing the press articles that the unknown murderer had sent numerous messages taunting the police and threatening further murders. This correspondence became one of the enduring legends of the Ripper case. However, the opinions of modern scholars are divided upon which, if any, of the letters should be considered genuine. The "Dear Boss" letter is one of three named most frequently as potentially having been written by the killer, and a number of authors have tried to advance their theories as to the Ripper's identity by comparing handwriting samples of suspects to the writing within the "Dear Boss" letter.[3]

Like many documents related to the Ripper case, the "Dear Boss" letter disappeared from the police files shortly after the investigation into the murders had ended.[12] The letter may have been kept as a souvenir by one of the investigating officers. In November 1987, the letter was returned anonymously to the Metropolitan Police, whereupon Scotland Yard recalled all documents relating to the Whitechapel Murders from the Public Record Office, now The National Archives, at Kew.[13]

Journalist's confession

In 1931, a journalist named Fred Best was reported to have confessed that he and a colleague at The Star newspaper named Tom Bullen[14] had written the "Dear Boss" letter, the "Saucy Jacky" postcard, and other hoax messages purporting to be from the Whitechapel Murderer—whom they together had chosen to name Jack the Ripper—in order to maintain acute public interest in the case and generally maintain high sales of their publication.[15][n 3]

Calligraphy and linguistic analysis

The handwriting of the letter "Dear Boss" was compared to that of the supposed diary of James Maybrick in 1993. The report noted that the "characteristics of the Dear Boss letter follow closely upon the round hand writing style of the time and exhibit a good writing skill."[15]

In 2018, a forensic linguist based at the University of Manchester named Andrea Nini stated his conviction that both the "Dear Boss" letter and the "Saucy Jacky" postcard had been written by the same individual.[9] Commenting upon his conclusions, Dr Nini stated: "My conclusion is that there is very strong linguistic evidence that these two [pieces of correspondence] were written by the same person. People in the past had already expressed this tentative conclusion, on the basis of similarity of handwriting, but this had not been established with certainty."[17]

Notes

- ↑ The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was a postcard addressed to the Central News Agency postmarked 1 October 1888. The author of this postcard is believed to be the same individual[8] who authored the "Dear Boss" letter.[9]

- ↑ A third letter, dated 6 October and posted to an unknown eyewitness (believed to be either Israel Schwartz or Joseph Lawende) is also believed to have been authored by the same individual responsible for the "Dear Boss" letter and the "Saucy Jacky" postcard. Written in red ink and also signed Jack the Ripper, the author of this letter threatens to murder the recipient if he assists police with their enquiries. The letter concludes by threatening the recipient: PS You see I know your address.[11]

- ↑ Chief Inspector John Littlechild is known to have stated in 1913 that senior Scotland Yard investigators had "generally believed" Bullen, whose full name was Thomas J. Bulling, to be responsible for the letters.[16]

References

- ↑ "Jack the Ripper Letters Suggest Newspaper Hoax". BBC News. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ "Did Francis Craig Write the Famous Jack the Ripper Letters?". The Telegraph. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 Sugden, Philip (2002). The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. New York: Carroll & Graf. pp. 260–270. ISBN 978-0-7867-0932-8.

- ↑ "Treasures from The National Archives: Jack the Ripper". nationalarchives.gov.uk. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Casebook: Jack the Ripper article on the Ripper letters

- ↑ Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia ISBN 978-1-553-45428-1 p. 159

- ↑ Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia ISBN 978-1-844-54982-5 p. 56

- ↑ Jack the Ripper: Case Solved? ISBN 978-1-326-38968-0 pp. 56-57

- ↑ Sex, Lies, and Handwriting: A Top Expert Reveals the Secrets Hidden in Your Handwriting ISBN 978-0-743-28810-1 p. 25

- ↑ Jack the Writer: A Verbal & Visual Analysis of the Ripper Correspondence ISBN 978-1-608-05751-1 p. 50

- ↑ Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Casebook ISBN 978-1-445-61786-2 p. 85

- ↑ "Jack the Ripper Letters | Dear Boss Letter | From Hell Letter | Saucy Jack Postcard". whitechapeljack.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-03.whitechapeljack.com

- ↑ The Dreadful Acts of Jack the Ripper and Other True Tales of Serial Murder ISBN 978-1-981-58780-3 p. 4

- 1 2 Joe Nickell, Real or Fake: Studies in Authentication, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2009. pp.44-7.

- ↑ "A Look at Some of the Known Letter Writers". jack-the-ripper.org. 2 April 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ↑ "Jack the Ripper Letter Mystery Solved by Manchester Researcher". manchester.ac.uk. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Cited works and further reading

- Begg, Paul (2004). Jack the Ripper: The Facts. United States of America: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 197–216. ISBN 978-0-760-77121-1.

- Begg, Paul; Fido, Martin (2015) [2010]. The Complete Jack The Ripper A-Z - The Ultimate Guide to The Ripper Mystery. Marylebone: John Blake Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-844-54797-5.

- Evans, Stewart; Skinner, Keith (2001). Jack the Ripper: Letters From Hell. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-2549-5.

- Gibson, Dirk C. (2013). Jack the Writer: A Verbal & Visual Analysis of the Ripper Correspondence. Bentham Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-608-05751-1.

- Sugden, Philip (2002). The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-0932-8.

- Trow, M. J. (2019). Interpreting the Ripper Letters: Missed Clues and Reflections on Victorian Society. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-526-73929-2.

- Whittington-Egan, Richard (2013). Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Casebook. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-61786-2.

External links

- The "Dear Boss" letter at casebook.org

- Jack the Ripper letters: "Dear Boss" at whitechapeljack.com

- "Dear Boss" letter: How Jack the Ripper got his name at britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk