Dearborn Park is a residential Chicago neighborhood located in the Loop and Near South Side community areas of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The area is known for its unique architecture,[1] green spaces,[2] and proximity to the city's downtown area and many cultural and recreational attractions.[3]

The Dearborn Park neighborhood comprises two distinct sub-areas: Dearborn Park I and Dearborn Park II.[4] The former is in the Loop community area and is bounded by State Street to the east, Clark Street to the west, Polk Street to the north and Roosevelt Road to the south.[5] The latter, located in the Near South Side community area, is directly south of Dearborn Park I, sharing the same east and west borders and bounded north by Roosevelt Road and south by 15th Street.[5] Despite the official community area designations, residents of Dearborn Park describe their neighborhood as being part of the South Loop.[5]: 187

History

Early Development

Dearborn Park, like most of Chicago, was originally the home of Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Miami, and other Native American tribes and nations.[6] The defeat of Sauk warrior and leader Black Hawk led to the ceding of the last Potawatomi lands around Chicago in an 1833 treaty, and Chicago was incorporated as a town that year.[6]

.jpg.webp)

Shortly thereafter, the neighborhood was developed by German and Irish immigrants who came to Chicago in the 1830s and 1840s to dig a shipping canal.[5]: 8 Their initial shantytown of wood cottages soon grew to host Italian immigrants, as well as freed and escaped slaves.[5]: 9

By the 1870s, the neighborhood served as a home to many Jewish immigrants from Russia and Poland,[7] as well as working-class and middle-class African Americans.[8] The neighborhood, part of the infamous Levee District,[9] had also earned a reputation for vice, with many "houses of ill-fame."[10]

The neighborhood was unscathed by the 1871 Chicago Fire but was not so lucky with the 1874 Chicago Fire, which destroyed most of the buildings in the area.[8]

In the aftermath of the 1874 fire, much of the land that is now Dearborn Park was purchased by real estate promoter John B. Brown and his associates, who saw the potential of southside access to the city by rail and acquired the land, principally for the Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad (C&WI) but other rail lines also bought nearby land.[11] (Perhaps not surprising to those who live in Chicago, there were accusations of bribery[12] and self-dealing[13] regarding the acquisition of the land.) The investment in the rail lines culminated in the opening of Dearborn Station at the northern border of Dearborn Park in 1885,[14] resulting in decades of economic growth in the area that reversed course into steep decline in the 1950s and 1960s.[15] Dearborn Station ultimately closed in 1971.[14]

The Plan for Dearborn Park

The genesis of Dearborn Park emerged during a 1970 meeting of three Chicago business leaders: Thomas G. Ayers, President of Commonwealth Edison; Donald M. Graham, CEO of Continental Illinois; and Gordon W. Metcalf, CEO of Sears, Roebuck & Co..[5]: 2

Looking south from the 37th floor of the brand-new First National Bank Building (now Chase Tower), they expressed concerns regarding the area to the south of the Chicago Loop.[5]: 2

The run-down area, impacted negatively by the decline of the rail industry and other factors, comprised abandoned railyards, a thriving vice district and many vacant, vandalized buildings.[5]: 10

.jpg.webp)

Prior efforts to transform the rail yard area had failed. Mayor Richard J. Daley had earlier sought to build a University of Illinois campus on the rail yards to replace the cramped, two-year branch on Chicago's Navy Pier, but had given up after failed negotiations with the railroad companies that owned the land.[5]: 9 The Chicago Central Area Committee (CCAC), created in 1956 to provide a unified voice to business leaders in redevelopment planning for the downtown area,[16] had also worked diligently on planning new uses for the railroad land, even since its founding days, but had made very little progress.[16]: 199–208

Ayers, Graham and Metcalf co-funded a small initial consulting study to evaluate options for the land.,[5]: 10–11 which confirmed the potential of the project but also identified numerous challenges, not the least of which was that 13 railroad companies owned pieces of the land, singly or in combination with each other.[5]: 13

This initial analysis led to a much larger study and plan, prepared by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM),[1]: 535 as well as the formation of a corporation, initially called Chicago 21 and later renamed to Dearborn Park Corporation, to fund the effort.[5]: 73

By 1972, the group, which had expanded to include representatives of leading Chicago businesses and civic, labor, education and religious institutions,[17] in partnership with the CCAC, had developed a plan for the City of Chicago, entitled "Chicago 21", which advocated the creation of an as-yet-unnamed "South Loop New Town" residential area, which eventually was branded as Dearborn Park.[1]: 535

Controversy

The proponents of Dearborn Park believed their project would stabilize the South Loop.[1]: 535 They wanted Dearborn Park: to be a catalyst for a new community on the barren rail yards south of the Loop; to halt the deterioration of the downtown area, strengthen its property values and add to the city's tax base; and to create an economically and racially integrated community "from the subsidized level to the semi-luxury level."[5]: 16

Activists in Chicago saw things differently, viewing the Chicago 21 Plan, which envisioned changes not only to the rail yards but also to other neighborhoods near downtown, as the city's intention to develop a two-tiered city to further segregate Chicago economically and racially. Activist Helen Shiller wrote in her memoir that: "It looked like the downtown was being fortified to protect the privileged while providing a catalyst to take on surrounding neighbors to whiten the inner city." A coalition of five nonprofits formed the Campaign to Stop the Chicago 21 Plan.[18]

The CCAC responded by pledging matching planning grants to the affected neighborhoods, an offer that was accepted by two of the affected communities.[19] Ultimately, the opposition receded, with the group had decided they had lost the battle to stop the first phase of Dearborn Park and the redevelopment of the South Loop, although Shiller later expressed regrets that they had given up too soon.[18]: 175

Acquiring the Land

As the group pursued negotiations with the railroad companies, they were surprised to learn in 1972 that Henry Crown, the head of one of America's wealthiest families, was also attempting to buy the rail yards, doing so on behalf of his friend George "Papa Bear" Halas, owner of the Chicago Bears, who wished to build a replacement stadium for Soldier Field inside of the rail yard land.[5]: 26–27

Halas gained control of the property, negotiating a price for the 51 acres of $3.25 a square foot, half the lowest price the South Loop group had been able to negotiate, and amounting to a total purchase price of $7.3 million for the land.[5]: 36 Halas' ability to use the land for a stadium required the consent and support of Mayor Daley, which was not forthcoming; Daley preferred a residential development.

In January 1974, seeing that Halas might not be successful, the South Loop group formalized its activities by forming the Chicago 21 Corporation, an investment vehicle that would be limited to a 6.5 percent return on investment, as the civic leaders did not want to be viewed as profiting irresponsibly from the project.[5]: 43 The group quickly raised $10 million, anchored by eight $1 million investments coming from large Chicago-area businesses.[5]: 42

In 1975, Halas, recognizing that he would not get mayoral support, reluctantly agreed to transfer his real estate option to Chicago 21, asking only to be reimbursed for his expenses and his deposit—a total of $100,000.[5]: 58 Chicago 21 Corporation had the land it needed, albeit only 51 acres, considerably less than the 200, 350, or 600 acres that had been mentioned in early plans.

Choosing the Name

In 1974, a naming consultant had been engaged to brand the new neighborhood, with short-list candidates including Friend Town, Oasis, Fellowship, Mecca, Rail Town, Marquette Place, Burhan Place and Greenville — but none of the proposed options was selected and it would be two years until a name for the community was finalized.[5]: 56

In December 1976, the Chicago 21 shareholders held their annual meeting and approved the Dearborn Park name, paying homage to Chicago's premier architectural street, to Fort Dearborn and to Dearborn Station.[5]: 73 At this same meeting, the Chicago 21 Corporation changed its entity name to Dearborn Park Corporation, in part, according to one shareholder, simply to confound the Coalition to Stop Chicago 21, which opposed the development.[5]: 73

Dearborn Park I

The newly named Dearborn Park Corporation decided to construct the community in two phases, with the first phase — 1,456 housing units — being built on 24 acres north of Roosevelt Road.[5]: 67 On the north side of the property, the land bordered Dearborn Station, which had quietly been purchased by one of the early Project 21 backers in 1982, for $1 million and a commitment to invest $10 million in restoring the station.[5]: 131

Construction on the first phase started in 1977. The corporation also sold some parcels to private developers for later building.[17]

As buildings were completed, buyers signed up. Initial demand for units was strong, even though the community at that time had no parks, no schools and no grocery store.[5]: 131 By mid-1980, 90 percent of the 480 completed units had been sold.[5]: 131 Subsequent demand weakened during the recession of the early 1980s but took off again when the recession ended, interest rates came down, and the Board of Education announced plans to open the new South Loop Elementary School at the north end of Dearborn II in early 1988.[17] By the end of 1986, 2,000 people were living in Dearborn Park I.[5]: 67

Dearborn Park II

The approach to Dearborn Park II was different from that of Dearborn Park I, in that the land was sold to multiple private developers. The first units in Dearborn Park II were offered for sale in late 1989, with the development of the community being delayed by unmet infrastructure needs that were being finalized with Mayor Harold Washington, replacing prior Mayor Eugene Sawyer who had shoveled the first dirt at the groundbreaking of Dearborn Park II in late 1988.[5]: 165–166

486 homes were constructed on 27 acres, making Dearborn Park II less dense than Dearborn Park I, and the units sold as soon as they were produced.[5]: 167

Demographics

In 1997, Crain's Chicago Business commemorated the 20th anniversary of Dearborn Park, describing it as a neighborhood of 5,000 residents that had "developed into a stable, racially integrated area" and that was an "almost exclusively middle-class enclave isolated from surrounding low-income neighborhoods."[20] Noting that there were 1,700 saleable housing units in the area, Crain's reported that "residents are mostly couples and families who bought townhouses" and that the "neighborhood has a stable racial mix: about 50% Anglo and 35% African-American, with the remainder Asian and Hispanic."[20]

According to 2020 Census Data, there were 3,303 people and 1,807 households residing in the area.[21] The racial makeup of the area was 54.20% White, 15.50% African American, 23.50% Asian, 4.09% from other races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.68% of the population.[21] Age distribution for the area is similar to other nearby communities, with 14.50% under the age of 18, 33.83% from 18 to 39, 35.90% from 40 to 64, and 15.80% who were 65 years of age or older.[21] The median household income for the area was $98,500 as opposed to $63,300 for the Chicago area.[21]

Landmarks

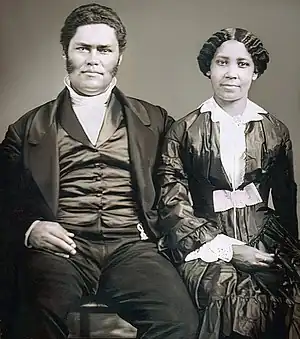

- Site of the John and Mary Jones House (1857-1872), located at 218 Edina Place (later Plymouth Court, and now corresponding approximately to 946 South Plymouth Court / 947 South Park Terrace).

Notable people

- John Jones (1832–1901), an American abolitionist, businessman, civil rights leader and philanthropist. His home at the corner of Plymouth Court and 9th Street in Dearborn Park is now a Chicago historic landmark.

- Mary Jane Richardson Jones (1819-1909), an American abolitionist, philanthropist, and suffragist. Her home at the corner of Plymouth Court and 9th Street in Dearborn Park is now a Chicago historic landmark. A Chicago park was named in Mary Jones' honor in 2005.[22]

Transportation

Dearborn Park is easily accessible via public transportation. Nearby Chicago "L" CTA stations include LaSalle on the Blue Line; LaSalle/Van Buren on the Brown Line, Pink Line and Purple Line; Harrison on the Red Line; and Roosevelt on the Red Line, Green Line and Orange Line.

Local parks

| Park Name | Address |

|---|---|

| Cotton Tail Park | 44 W. 15th St. Chicago, IL 60616 |

| Dearborn (Henry) Park | 865 S.Park Terrace Chicago, IL 60605 |

| Roosevelt (Theodore) Park | 62 W. Roosevelt Rd. Chicago, IL 60605 |

Legacy

Views of Dearborn Park continue to evolve but have at times been diametrically opposite.

Tom Cokins, a Chicago city planner, wrote that "Today over 100,000 people make downtown Chicago their home, a migration sparked by the success of Dearborn Park. This South Loop community serves as a model of urban renewal unlike any other in the United States."[5]: cover

On the other hand, historian Edward Kantowicz castigated the early community, writing in 1998 that "They built a wall around their neighborhood and provided only one automobile entrance. They refused to send their children to a public school built expressly for them because of the presence of children from nearby public housing projects...In short, their community is a suburban development uncomfortably plunked down in the city."[23]

Additional Reading

References

- 1 2 3 4 Beedle, Lynn S.; Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (1986). Advances in tall buildings. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 536–537. ISBN 978-0-442-21599-6.

- ↑ Chappell, S.A. (2007). Chicago's Urban Nature: A Guide to the City's Architecture + Landscape. Chicago Architecture and Urbanism Series. University of Chicago Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-226-10139-2. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ Wukas, M. (2004). Newcomer's Handbook for Moving to and Living in Chicago: Including Evanston, Oak Park, Schaumburg, Wheaton, and Naperville. First Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-912301-53-2. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ Charles Hayes (October 20, 1991). "Terrace Homes Add Latest Chapter To Dearborn Park's Developing". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Wille, Lois (1998). At Home in the Loop: How Clout and Community Built Chicago's Dearborn Park. SIU Press. Illustrations Section, After Page 78, Map: Near South Development, 1977-1997. ISBN 978-0-8093-2225-1.

- 1 2 "An Exploration of Native American History in Chicago with Geoffrey Baer". WTTW. 2021. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ↑ Garel-Frantzen, Alex (November 19, 2013). Gangsters and organized crime in Jewish Chicago. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1626191938.

- 1 2 "THE FIRE.: The Scenes of Oct. 9, 1871, Repeated on a Small Scale". Chicago Daily Tribune. Vol. 27, no. 326. July 15, 1874. p. 1.

- ↑ Blair, Cynthia M. (2018-09-28). I've Got to Make My Livin': Black Women's Sex Work in Turn-of-the-Century Chicago. University of Chicago Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-226-59758-4.

- ↑ "Fire of 1874". Chicagology. 203. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ↑ "Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad Company Correspondence". The Newberry Library. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ "Railroad Involved in Bribery Charge" (PDF). The New York Times. April 30, 1910. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ Everybody's Magazine. North American Company. 1911. p. 466. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- 1 2 "A History of the Dearborn Station". Dearborn Station Management Co. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ Saunders, W.S. Urban Planning Today: A Harvard Design Magazine Reader. Harvard Design Magazine Readers. U of Minnesota Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4529-0872-4. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- 1 2 Rast, Joel (2019). The Origins of the Dual City. The University of Chicago Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-226-66144-5.

- 1 2 3 J. Linn Allen (June 18, 1989). "New At Dearborn Park: Condos That Look Old". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- 1 2 Shiller, Helen (2022). Daring to Struggle, Daring to Win: Five Decades of Resistance in Chicago's Uptown Community. Haymarket Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1642598421.

- ↑ Clavel, Pierre; Wiewel, Wim (1991). Neighborhood Mayor: Harold Washington and the Neighborhoods: Progressive City Government in Chicago, 1983–1987 (PDF). Rutgers University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0813517261. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- 1 2 Hinz, Greg (1 December 1997). "South Side story". Crain's Chicago Business. 20 (48): 10. Retrieved 14 April 2023. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States – Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ↑ "Jones (Mary Richardson) Park". Chicago Park District. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ↑ Kantowicz, E. R. (1998). "eview of At Home in the Loop: How Clout and Community Built Chicago's Dearborn Park, by L. Wille". Illinois Historical Journal. 91 (1): 63–64. JSTOR 40193269. Retrieved 14 April 2023. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

.jpg.webp)