Frederick John White was a private in the British Army's 7th Hussars. While serving at the Cavalry Barracks, Hounslow, in 1846, White touched a sergeant with a metal bar during an argument while drunk. A court-martial sentenced him to 150 lashes with a cat of nine tails. The flogging was carried out on 15 June with White tied to a ladder in front of the regiment. White was afterwards admitted to hospital where he initially progressed well but eventually deteriorated and died on 11 July.

An army autopsy recorded that White's death was by natural causes, resulting from an inflammation of the pleura and cardiac covering, and his body was sent for a church burial at St Leonard's Church, Heston. The vicar, however, had learnt of the flogging and alerted the Middlesex coroner Thomas Wakley. Wakley, an opponent of flogging, ordered an inquest and arranged for two further autopsies to be performed. The last of these, carried out by Erasmus Wilson, reported that White's death was a direct result from the flogging. The inquest jury, on 4 August, returned the verdict that White's case was a result of the flogging and called for its use to be discontinued.

The case resulted in publicity for the cause of abolition, though some medical professionals disputed the inquest findings. Within days the commander-in-chief of the British Army, the Duke of Wellington, ordered that flogging sentences were not to exceed fifty lashes. The prime minister Lord John Russell noted in the House of Commons that he supported the eventual abolition of the punishment. Despite this promise, flogging remained available to the army until 1881, when corporal punishment was abolished as part of the Childers Reforms.

Background

Flagellation, referred to as flogging in the British military, was a form of corporal punishment inflicted by means of whipping the back of the prisoner.[1] Flogging was authorised in the British Army by the Mutiny Act 1689 and by the 18th century was in common use, with sentences of up to 1,000 lashes not being unusual.[1][2] In higher sentences the punishment was carried out in stages with the victim being given periods of rest in between to allow the skin to heal.[2] Deaths from floggings were not unknown, though were more common in foreign postings, such as to British India, than on home service. When deaths occurred the cause was usually attributed to fever or disease rather than from the punishment.[3]

Incident and punishment

Frederick John White was a soldier in the 7th (The Queen's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) (commonly known as the 7th Hussars), born in January 1819 and originating from Nottingham.[1][4][5] He had previously been punished for infractions by means of punishment drills and, prior to his 1846 sentence, had only spent one period in hospital, after being kicked by a horse.[5] When he was with the regiment at the Cavalry Barracks, Hounslow, in 1846 White had, whilst drunk, argued with his sergeant and touched him on his chest with a metal bar. He was placed under arrest and brought before a district court-martial 4–5 days later.[5][1][3] The court sentenced him to 150 lashes with a cat of nine tails, made from nine knotted leather thongs, the maximum number of lashes the court was permitted to sentence.[1][6] This was probably the first time White had been flogged.[5] In the 7th Hussars corporal punishment was administered by the regimental farriers, men experienced in this role on campaign, who were instructed to strike as hard as they could or risk punishment themselves. One private, with experience in other regiments, recounted that the 7th Hussars flogged more harshly than other units where trumpeters, who were often boys, administered the punishment.[7]

.jpg.webp)

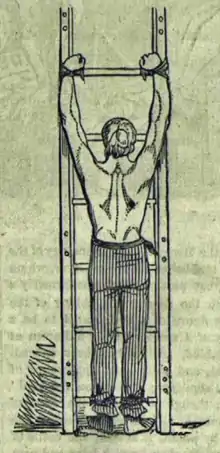

The flogging was carried out on 15 June 1846, in front of 200–300 men of the regiment which was formed in a 3-sided square in the riding school.[5][8] After being read the decision of the court-martial White was stripped to the waist and tied by his arms and legs with cord to a ladder which was nailed to the wall at the open side of the square.[3][5][7] At around 9 am the regiment's commander, Lieutenant-Colonel John Hames Whyte, gave the order to commence the punishment. The regimental adjutant Lieutenant Ireland then gave the order to Farrier-Major Critton.[5]

Critton made the first strokes with the cat, alternating with Farrier Evans after each 25 or 50 lashes (the sources vary) to rest their arms.[5][1] Sergeant Patman counted out the strokes, which were made at the rate of one every twelve seconds.[5][1] White's shoulders began bleeding after the first 20 strokes but he did not cry out in pain at any time during the punishment.[1][3] The cat was swapped for a fresh one after 100 lashes at which point White asked the farriers to strike "lower, lower", whereupon they adjusted their aim.[8] This request may have been so that the lash fell upon skin already damaged by flogging, and so numbed to the pain, rather than the skin on the back of his neck.[9]

Colonel Whyte and the regimental surgeon Dr James Law Warren were present throughout. Warren did not intervene to check on White at any point during the punishment.[1] At one point White asked for a drink of water, which was given.[3] At least one corporal and one private fainted while witnessing the punishment, though one witness at the coroner's court recounted that six men fainted.[8][7] By the end of the punishment White had suffered significant blood loss, which soaked his trousers; this occurred despite regulations stating that flogging was not intended to break the skin.[3][1] His shirt, doused in water, was placed over his back and he was covered with his overcoat and taken to the barracks hospital.[3] Whyte announced to the regiment that he was sorry such a "brutish exhibition" as White's offence should be committed in the regiment and he was determined to stop such conduct.[8]

Treatment and death

White whistled on his entry into the hospital, where the blood was sponged from his still-bleeding back by an orderly and another patient.[7][10] White was not seen by a doctor for another 90 minutes when Warren, accompanied by Whyte, visited. Neither officer spoke with White or examined his back. Warren returned at 10 pm to examine White's back which was wounded in an area around 6 inches (15 cm) in height and 4–5 inches (10–13 cm) in width between his shoulder blades. White's pulse was not taken on the first day.[7]

White's back was washed with lukewarm water and treated with a cetaceous ointment and basic lead acetate.[3] Warren placed him on a restricted diet of 0.25 pounds (0.11 kg) of potatoes and 0.75 pounds (0.34 kg) of bread per day until 9 July when he was placed on a "half diet" of 1 pound (0.45 kg) of bread, 0.5 pounds (0.23 kg) of meat, 1 imperial pint (0.57 L) of soup and 2 imperial pints (1.1 L) of tea.[11] White could not eat his full allowance after 5 July, eating, for example, just one potato on 6 July.[12] During his time in hospital White complained that he had not been in a fit state to be flogged owing to an existing chest complaint.[12][8]

The skin on White's back healed quickly though from early July his condition deteriorated. White complained of pain in his right side and by 6 July was bed-ridden.[3][5] On 9 July White's back and chest, which had broken out in boils, was treated with a mustard plaster.[10][11] On 11 July White lost sensation in his extremities and had difficulty passing urine.[3] His back was inflamed and his skin was cold and moist.[3][10] First Class Staff Surgeon John Hall was called to attend White on the order of Sir James McGrigor. He attended but found it was too late to intervene and White died in his presence at 8.30 pm.[13][14]

Autopsies

Warren carried out an autopsy on White assisted by Hall and Dr Francis Reid.[14] He concluded that death was caused by inflammation of the pleura and cardiac covering, which he recorded on the death certificate.[15][14] Hall sent a separate report on the death to the Army Medical Department, noting that White's back was well healed.[14] White's body was sent for burial and the vicar was told he had died of a liver complaint. However the vicar became suspicious when he heard that White had been flogged and reported the death to the Middlesex coroner Thomas Wakley.[16][1] Wakley was a reformer, founder of The Lancet medical journal, and opponent of flogging. [1]

Wakley reviewed White's case, considered that the army's autopsy had been too cursory and ordered an inquest be held. He sent for surgeon and sanitary reformer Dr. Horatio Grosvenor Day to carry out a second autopsy. When Day reported, Wakley claimed that a misunderstanding had meant that White's spine had not been examined. This allowed him to order a third autopsy, which was carried out by renowned dermatologist Erasmus Wilson. Such an in-depth investigation was highly unusual at this time for the death of a mere army private.[14]

Wilson reported that the inflammation caused by the flogging penetrated the full depth of the skin. He found the spinal area had a "pulpy softening of the muscles", which he ascribed to the contraction of the muscles during the flogging. This softening may, however, have arisen as a result of bacterial infection of the blood, which was not yet known to science.[1] Wilson found that White's internal organs were inflamed, he described this as a direct result of the flogging and a contributory factor to White's death. He thought that the skin, which was well healed, disguised the internal issues.[1] Wilson also reported White had suffered "shock" to his nervous system, inflammation of the left lung and boils on his back.[9] Day dissented with Wilson's findings on the grounds that he did not consider that the pleura could be affected by the muscles.[14]

Inquest

Wakley's inquest first met on 15 July from 8 pm in the parlour of the George IV Inn on Hounslow Heath. Thirteen jurors were sworn in and the inquest attended by officers of the regiment and members of the public. The jury visited the barracks to view White's body whereupon Wakley discovered that part of the skin from White's back, measuring some 57 square inches (370 cm2), was missing having been removed during Warren's autopsy.[17] Wakley discovered that the army had made no effort to contact White's next of kin and adjourned the inquest at 10 pm to allow time for family members to be found, for Day's autopsy to be carried out and for Reid and Hall to be called to testify.[17][4] The inquest met again on 20 July at the same inn at 9.30 am. A large number of the public attended, including five magistrates. A solicitor, Mr G Clark, attended to represent the 7th Hussars.[4] Clark insisted that the regiment's adjutant, Ireland, be present throughout the inquest as he was his instructing party. The jury protested that Ireland might intimidate the soldiers called to testify but Wakley permitted him to remain.[5] White's brother had been located and attended as his next of kin.[4] After finding the issue with Day's autopsy not having investigated White's spine, Wakley adjourned the second day at 3.45 pm.[18]

The inquest reconvened from 9.30 am on 27 July, after Wilson had completed his autopsy.[18] In the course of questioning by Wakley, Warren stated that he had seen White on the day of the punishment and found him fit to receive it.[15] He denied making a statement, reported by a witness in the hospital, that White had died from the effects of the flogging. He stated that he found adhesions on White's heart during his autopsy and that, apart from inflammation of the heart and blood vessels, White was healthy.[13] Day and Reid stated that the hot weather of the summer of 1846 may have contributed to White's death.[14]

The jury reported back on the fourth and final day of the inquest, 4 August, that they considered White's death to have been caused by the flogging.[1] The question of culpability was legally difficult as wounding at the time was defined as breaking of the skin and White's skin was healed by the time of his death.[14] In their findings, the jury called for the public to send petitions to parliament to seek the abolition of flogging.[1]

Impact

The outcome of the inquest led to arguments in the medical press over the cause of death.[14] An unsigned article in the London Medical Gazette disputed the jury's findings and claimed that White had died because he was an alcoholic, though the author also thought that fifty lashes would have been a sufficient punishment. George Ballingall, Professor of military surgery at the University of Edinburgh, wrote in the Monthly Journal of Medical Science disputing Wakley and Wilson's impartiality and the quality of the evidence provided by Wilson. Wilson wrote a series of papers in the Lancet in which he claimed that much of the medical profession did not appreciate that the skin was an important organ capable of affecting the rest of the body.[9]

The case led to the foundation of the Flogging Abolition Society, chaired by Wakley, who first met in 1846.[9] A ballad named The Flogging Excitement at Hounslow, that argued the cause for abolition, was popular around the time of the inquest.[19] Its last lines were:[20]

Tied up hands and feet to a ladder,

While the sound of the cat reached afar,

Oh, Britain thy deeds make me shudder,

Remember poor White, the Hussar

Shortly after the inquest reported the commander-in-chief of the British Army, the Duke of Wellington, ordered that the maximum number of lashes be reduced to fifty.[1] On 7 August the prime minister, Lord John Russell, was questioned in parliament over the continued use of flogging in the army. He stated that Wellington had ordered that all soldiers sentenced to be flogged be examined by medical professionals to check they were fit to be so punished and that the weather conditions at the time be taken account of. Russell stated that he looked forward to the time when flogging could be abolished in the army but that he and Wellington considered it necessary for the immediate future. He stated that his government had constructed numerous prisons for use by the army as an alternative to corporal punishment and that the proportion of men flogged each year had fallen from 1:108 in 1838 to 1:189 in 1845. He noted that the introduction of good conduct payments, pay rises in recognition of long service, the awarding of commissions to those in the ranks and the establishment of libraries, savings banks and gardens had promoted good discipline in the army.[6]

The use of flogging in the army was restricted in 1859 so that, in peacetime, only those men considered of "bad character" could be flogged; the sentence remained freely available to courts-martial held in wartime.[21] The 1868 Cardwell Reforms further restricted the peacetime use to cases of mutiny and "aggravated insubordination and disgraceful conduct". It remained available in times of war for these two offences plus desertion, drunkenness while on duty or line of march, misbehaviour and neglect of duty.[22] Flogging sentences were restricted to 25 lashes in 1879, by which time the punishment was little used.[23][1] The use of all corporal punishment in the army was abolished as part of the 1881 Childers Reforms.[23][9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Garrisi, Diana (3 February 2015). "What actually happens when you get flogged". New Statesman. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- 1 2 Garrisi, Diana (November 2015). "On the skin of a soldier: The story of flogging". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (6): 693–6. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.12.018. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 26686021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Garrisi, Diana (November 2015). "On the skin of a soldier: The story of flogging". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (6): 694. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.12.018. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 26686021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 396. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 397. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Flogging in the Army: HC Deb 07 August 1846 vol 88 cc374-463". Hansard. House of Commons. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 399. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 398. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Garrisi, Diana (November 2015). "On the skin of a soldier: The story of flogging". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (6): 696. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.12.018. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 26686021.

- 1 2 3 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 400. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 402. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 403. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 408. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Garrisi, Diana (November 2015). "On the skin of a soldier: The story of flogging". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (6): 695. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.12.018. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 26686021.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 407. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- ↑ "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 406. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 395–433. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- 1 2 "Fatal Case of Military Flogging at Hounslow". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 66 (169): 404. 1 October 1846. ISSN 0963-4932. PMC 5801876. PMID 30331117.

- ↑ Hepburn, James G. (2000). A Book of Scattered Leaves: Poetry of Poverty in Broadside Ballads of Nineteenth-century England : Study and Anthology. Bucknell University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8387-5397-2.

- ↑ Firth, C. Harding (1922). "Flogging in the Army". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 1 (6): 257. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44220241.

- ↑ Blanco, Richard L. (1968). "Attempts to Abolish Branding and Flogging in the Army of Victorian England Before 1881". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 46 (187): 140. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44230519.

- ↑ Blanco, Richard L. (1968). "Attempts to Abolish Branding and Flogging in the Army of Victorian England Before 1881". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 46 (187): 144. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44230519.

- 1 2 Blanco, Richard L. (1968). "Attempts to Abolish Branding and Flogging in the Army of Victorian England Before 1881". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 46 (187): 145. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44230519.