In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.[2]

A conquered people who were dediticii did not individually lose their freedom, but the political existence of their community was dissolved as the result of a deditio, an unconditional surrender.[3] In effect, their polity or civitas ceased to exist. Their territory became the property of Rome, public land on which they then lived as tenants.[4] Sometimes, this loss was a temporary measure, almost a trial period to see whether the peace held, while the people were being incorporated into Roman governance;[5] territorial rights for the people or property rights for individuals might then be restored by a decree of the senate (senatus consultum) once relations were perceived as having stabilized.[6]

In the Imperial era, there were three categories of people who held dediticius status defined as freedom without rights: the peregrini dediticii ("foreigners under treaty") who had surrendered; peregrini who had immigrated into the empire; and former slaves who were designated libertini qui dediticiorum numero sunt, freedmen who were counted as dediticii because of a penal status that denied them the citizenship usually bestowed with manumission.[7]

Dediticii ex lege Aelia Sentia

Under Augustus, in AD 4 the lex Aelia Sentia created a new class of freedmen who, while technically free, held no rights of citizenship, a status they shared with peregrini dediticii. The jurist Gaius called the status of dedicitius "the worst kind of freedom."[8]

If a slave during his servitude had been subjected to certain punishments but later freed (either by the master who punished him or by a subsequent owner), he was excluded from the political liberty that had customarily followed formal manumission in Republican Rome. Gaius describes these slaves as those "who have been chained by their masters as a punishment, or those who have been branded, or interrogated under torture concerning some wrongdoing and convicted of that offence, or handed over to fight in gladiatorial combat with swords or with wild beasts, or sent to the games (ludi), or thrown into custody" and then later manumitted.[9] They existed in a state of permanent delinquency (turpitudo).[10] A dediticius caught in adultery could be killed with impunity.[11] A manumitted slave would not become dediticius, however, if he had been bound while used as surety for a loan, or if the chaining was carried out by a mentally ill person (furiosus) or ward.[12]

Unlike the peregrini dedicitii, who could make a will under the local law of their community,[13] these dediticii were like slaves in holding no rights to succession and therefore could not create a stable family line through passing down property.[14] When they died, any property they had went to the person who had manumitted them.[15] Their assimilation to the status of foreigners under surrender has been somewhat perplexing to scholars; W. W. Buckland considered this one of the instances in Roman law of "rules … made to apply to cases quite different from that for which they were invented."[16]

The law also created a dilemma for owners particularly of agricultural slave crews. Chaining was a routine means of controlling and disciplining slaves that might be preferred to harsher punishments such as whipping, torture, or disfigurement. Employing it now meant that masters were automatically denying their slaves any hope of ever becoming citizens, a hope that had been used as a way to encourage them to work hard and willingly. The lex Aelia Sentia was thus one more way in which Augustus appropriated the traditional power of a paterfamilias to govern his own household.[17] Even if an owner acquired a slave who had been subjected to one of these forms of punishment, but did not himself chain or punish a slave and then manumitted him, the former slave still could not enjoy the rights of citizenship.[18]

These criminalized former slaves were characterized as a threat to society, and if they came within a hundred miles of Rome, they and their property could be seized.[19] The dediticius was then sold into perpetual slavery outside the hundred-mile radius. If released by his master, he became a slave of the Roman people, at the disposal of the state but with none of the privileges of the public slaves (servi publici) in civil service.[20]

Why the lex Aelia Sentia permitted the manumission of a slave perceived as a danger is not entirely clear.[21] Sales contracts sometimes stipulated a term of servitude, typically ranging from one to five years, after which time the slave was to be manumitted.[22] Augustus imposed a term of twenty to thirty years on war captives who had shown resistance;[23] age and the physical toll of slavery well past the average life expectancy of slaves might have been thought to reduce the threat.

Dediticii and the Constitutio Antoniniana

The Constitutio Antoniniana of AD 212, with which Caracalla granted universal citizenship to all free men within the empire, has sometimes been interpreted as excluding those who had become subjects through a deditio (that is, a person who was a dediticius).[24] However, this constitution does not survive in a single, unified, intact text; the wording pertaining to the excluded dediticii is vexed; and Ulpian and Dio Cassius both clearly state that the grant was universal.[25]

On the basis of the Tabula Banasitana, it has been argued that the intention was to exclude recent dediticii whose loyalty was not assured.[26] But before the constitutio, there had been no bar to peregrini dediticii being granted citizenship, and those who served in the Roman military—as the "barbarian" troops of the numeri did—regularly became citizens as a reward at the end of their service.[27] If all foreign provincials under treaty were excluded, it becomes harder to discern how the constitutio would achieve its aims of broadening the tax base and enlarging the cultivation of Roman religion.[28] The granting of citizenship could not be meaningfully "universal" if it excluded so many people, and though no similar large-scale expansions of citizenship are known, by the 5th century the free inhabitants of the empire are clearly represented in the sources as all citizens.[29] "Potentially disloyal" would be a nebulous category not readily defined as a matter of law, and a likely solution is that only a subgroup of dediticii were excluded, the former slaves treated as criminals and barred from citizenship by the lex Aelia Sentia.[30] In this view,[31] the dediticii exception in Caracalla's constitutio was thus carefully limited and framed so as not to contravene the 200-year precedent of the Augustan lex.[32]

Dediticii are absent from later Imperial law, and Justinian (reigned AD 527–565) abolished the status as already obsolete[33] in the year 530.[34] However, an early medieval legal text correlates wergilds, the compensation paid for the taking of a life according to the victim's social status, with Roman statuses including that of dediticius, though wergilds were not a feature of Roman law.[35]

References

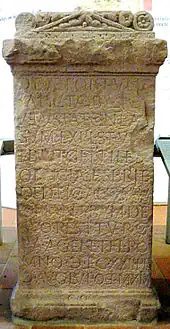

- ↑ Pat Southern, "The Numeri of the Roman Imperial Army," Britannia 20 (1989), p. 139, no. 16; CIL 13.6592 = AE 1983, 729); further discussion by Iiro Kajanto, "Epigraphical Evidence of the Cult of Fortuna in Germania Romana," Latomus 47:3 (JUILLET-SEPTEMBRE 1988), pp. 570–572, 578.

- ↑ Adolph Berger, s.v. "Dediticii", Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philosophical Society, 1953), p. 427.

- ↑ Christian Baldus, "Vestigia pacis. The Roman Peace Treaty: Structure or Event?" in Peace Treaties and International Law in European History from the Late Middle Ages to World War One (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 122.

- ↑ Herbert W. Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 85 (1954), p. 192.

- ↑ Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," p. 194.

- ↑ L. De Ligt, "Provincial Dediticii in the Epigraphic Lex Agraria of 111 BC?" Classical Quarterly 58:1 (2008), pp. 359–360.

- ↑ Herbert W. Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," pp. 188–189, 191.

- ↑ Pessima … libertas: Gaius, Institutiones 1.26, as cited by Deborah Kamen, "A Corpus of Inscriptions: Representing Slave Marks in Antiquity," Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 55 (2010), p. 104.

- ↑ Ulrike Roth, "Men Without Hope," Papers of the British School at Rome 79 (2011), p. 90, citing Gaius, Institutes 1.13 and pointing also to Suetonius, Divus Augustus 40.4

- ↑ Luigi Pellecchi, "The Legal Foundation: The leges Iunia et Aelia Sentia", in Junian Latinity in the Roman Empire vol. 1: History, Law, Literature (Edinburgh University Press, 2023), p. 62 and n. 34, citing Gaius, Institutiones 1.15.

- ↑ Simon Corcoran, "Junian Latinity in Late Roman and Early Medieval Texts: A Survey from the Third to the Eleventh Centuries AD," in Junian Latinity in the Roman Empire, p. 136.

- ↑ Corcoran, "Junian Latinity in Late Roman and Early Medieval Texts," p. 135, n. 26.

- ↑ Egbert Koops, "Masters and Freedmen: Junian Latins and the Struggle for Citizenship," Integration in Rome and in the Roman World: Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Lille, June 23-25, 2011) (Brill, 2014), pp. 115–116, n.69.

- ↑ Roth, "Men Without Hope," p. 91.

- ↑ Pellecchi, "The Legal Foundation," p. 63.

- ↑ W. W. Buckland, The Roman Law of Slavery: The Condition of the Slave in Private Law from Augustus to Justinian (Cambridge University Press, 1908), p. 534.

- ↑ Roth, "Men Without Hope," pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Roth, "Men Without Hope," pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Jane F. Gardner, "Slavery and Roman Law," in The Cambridge World History of Slavery (Cambridge University Press, 2011), vol. 1, p. 429.

- ↑ Buckland, The Roman Law of Slavery, p. 596.

- ↑ Pedro López Barja, "The Republican Background and the Augustan Setting for the Creation of Junian Latinity," in Junian Latinity in the Roman Empire, p. 82.

- ↑ Thomas E. J. Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome," Classical Quarterly 35:1 (1985), pp. 169–173.

- ↑ Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission," p. 170, n. 21, citing Suetonius, Augustus 21; Cassius Dio 53.25.4.

- ↑ Olivier Hekster, Rome and Its Empire, AD 193–284 (Edinburgh University Press, 2008), p. 47.

- ↑ Herbert W. Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," pp. 188–189, 191.

- ↑ A. N. Sherwin-White, "The Tabula of Banasa and the Constitutio Antoniniana," Journal of Roman Studies 63 (1973), pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," p. 194.

- ↑ Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," pp. 188, 191.

- ↑ A. H. M. Jones, "Another Interpretation of the Constitutio Antoniniana," Journal of Roman Studies 26:2 (1936), pp. 224, 227.

- ↑ Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," p. 196.

- ↑ Accepted also by t Koops, "Masters and Freedmen: Junian Latins and the Struggle for Citizenship," pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Benario, "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana," p. 196.

- ↑ Buckland, The Roman Law of Slavery, p. 402.

- ↑ Corcoran, "Junian Latinity in Late Roman and Early Medieval Texts," p. 141.

- ↑ Corcoran, "Junian Latinity in Late Roman and Early Medieval Texts," p. citing the 9th-century Aegidian Epitome (Par. Lat. 4416 f. 50v).