The Delta Works (Dutch: Deltawerken) is a series of construction projects in the southwest of the Netherlands to protect a large area of land around the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta from the sea. Constructed between 1954 and 1997, the works consist of dams, sluices, locks, dykes, levees, and storm surge barriers located in the provinces of South Holland and Zeeland.

The aim of the dams, sluices, and storm surge barriers was to shorten the Dutch coastline, thus reducing the number of dikes that had to be raised. Along with the Zuiderzee Works, the Delta Works have been declared one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

History

The estuaries of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Schelde have been subject to flooding over the centuries. After building the Afsluitdijk (1927 – 1932), the Dutch started studying the damming of the Rhine-Meuse Delta. Plans were developed to shorten the coastline and turn the delta into a group of freshwater coastal lakes. By shortening the coastline, fewer dikes would have to be reinforced.

Due to indecision and the Second World War, little action was taken. In 1950 two small estuary mouths, the Brielse Gat near Brielle and the Botlek near Vlaardingen were dammed. After the North Sea flood of 1953, a Delta Works Commission was installed to research the causes and develop measures to prevent such disasters in future. They revised some of the old plans and came up with the "Deltaplan".

Unlike the Zuiderzee Works, the Delta Plan's purpose is largely defensive and not for land reclamation.[1] The Delta Plan is a national programme and demands collaboration between the national government, provincial authorities, municipal authorities and the water boards. The plan consisted of blocking the estuary mouths of the Oosterschelde, the Haringvliet and the Grevelingen. This reduced the length of the dikes exposed to the sea by 700 kilometres (430 mi). The mouths of the Nieuwe Waterweg and the Westerschelde were to remain open because of the important shipping routes to the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp. The dikes along these waterways were to be heightened and strengthened. The works would be combined with road and waterway infrastructure to stimulate the economy of the province of Zeeland and improve the connection between the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp.

Delta law and conceptual framework

An important part of this project was fundamental research to come up with long-term solutions, protecting the Netherlands against future floods. Instead of analysing past floods and building protection sufficient to deal with those, the Delta Works commission pioneered a conceptual framework to use as norm for investment in flood defences.

The framework is called the 'Delta norm'; it includes the following principles:

- Major areas to be protected from flooding are identified. These are called "dike ring areas" because they are protected by a ring of primary sea defences.

- The cost of flooding is assessed using a statistical model involving damage to property, lost production, and a given amount per human life lost.

- For the purpose of this model, a human life is valued at €2.2 million (2008 data).

- The chances of a significant flood within the given area are calculated. This is done using data from a purpose-built flood simulation lab, as well as empirical statistical data regarding water wave properties and distribution. Storm behaviour and spring tide distribution are also taken into account.

The most important "dike ring area" is the South Holland coast region. It is home to four million people, most of whom live below normal sea level. The loss of human life in a catastrophic flood here can be very large because there is typically little warning time with North Sea storms. Comprehensive evacuation is not a realistic option for the Holland coastal region.

The commission initially set the acceptable risk for complete failure of every "dike ring" in the country at 1 in 125,000 years. But, it found that the cost of building to this level of protection could not be supported. It set "acceptable" risks by region as follows:

- North and South Holland (excluding Wieringermeer): 1 per 10,000 years

- Other areas at risk from sea flooding: 1 per 4,000 years

- Transition areas between high land and low land: 1 per 2,000 years

River flooding causes less damage than salt water flooding, which causes long-term damage to agricultural lands. Areas at risk from river flooding were assigned a higher acceptable risk. River flooding also has a longer warning time, producing a lower estimated death toll per event.

- South Holland at risk from river flooding: 1 per 1,250 years

- Other areas at risk from river flooding: 1 per 250 years.

These acceptable risks were enshrined in the Delta Law (Dutch: Deltawet). This required the government to keep risks of catastrophic flooding within these limits and to upgrade defences should new insights into risks require this. The limits have also been incorporated into the new Water Law (Waterwet), effective from 22 December 2009.

The Delta Project (of which the Delta Works are a part) has been designed with these guidelines in mind. All other primary defences have been upgraded to meet the norm. New data elevating the risk assessment on expected sea level rise due to global warming has identified ten 'weak points.' These have been upgraded to meet future demands. The latest upgrades are made under the High Water Protection Program.

Alterations to the plan during the execution of the Works

During the execution of the works, changes were made in response to public pressure. In the Nieuwe Waterweg, the heightening and the associated widening of the dikes proved very difficult because of public opposition to the planned destruction of important historic buildings to achieve this. The plan was changed to the construction of a storm surge barrier (the Maeslantkering) and dikes were only partly built up.

The storm-surge barrier

The Delta Plan originally intended to create a large freshwater lake, the Zeeuwse Meer (Zeeland Lake).[1] This would have caused major environmental destruction in Oosterschelde, with the total loss of the saltwater ecosystem and, consequently, the harvesting of oysters. Environmentalists and fishermen combined their efforts to prevent the closure; they persuaded parliament to amend the original plan. Instead of completely damming the estuary, the government agreed to build a storm surge barrier. This essentially is a long collection of very large valves that can be closed against storm surges.

The storm surge barrier closes only when the sea-level is expected to rise 3 metres above mean sea level. Under normal conditions, the estuary's mouth is open, and salt water flows in and out with the tide. As a result of the change, the weak dikes along the Oosterschelde needed to be strengthened. Over 200 km of the dike needed new revetments. The connections between the Eastern Scheldt and the neighboring Haringvliet had to be dammed to limit the effect of the salt water. Extra dams and locks were needed at the east part of the Oosterschelde to create a shipping route between the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp. Since operating the barrier has an effect on the environment, fisheries and the water management system, decisions made on opening or closing the gate are carefully considered. Also the safety of the surrounding dykes are affected by barrier operations.

Environmental policy implementations

In an attempt to restore and preserve the natural system surrounded by the dykes and storm-surge barrier, the concept 'building with nature' was introduced in revised Delta Program updates after 2008. The new integrated water management plan not only takes into account protection against flooding, but also covers water quality, leisure industry, economic activities, shipping, environment and nature. Whenever possible, existing engineering constructions would be replaced by more 'nature friendly' options in an attempt to restore natural estuary and tides, while still protecting against flooding.[2] In addition, building components of the reinforcements are designed in a way that they support formation of entire ecosystems.[3] As part of the revision, the Room for the River projects, enabled nature to occupy space by lowering or widening the river bed.[4] In order to establish this, agricultural flood plains are turned into natural parks, excavated farmland is used for wild vegetation and newly excavated lakes and bypasses create habitats for fish and birds.[5] Along the coast, natural sand is added each year to allow sand to blow freely through the dunes instead of having the dunes held in place by planted vegetation or revetments.[6] Although the new plan brought along additional cost, it was received favourably. The re-considerations of the Delta Project indicated the growing importance of integrate environmental impact assessments in policy-making.

Environmental effects

The Delta Project of which the Delta Works are part of was originally designed in a period of time when environmental awareness and ecological effects of engineering projects were barely taken into consideration.[7] Although the level of awareness for the environment grew throughout the years, the Delta Project has caused numerous irreversible effects on the environment in the past. Blocking the estuary mouths did reduce the length of dykes that otherwise would have to be built to protect against floods, but it also led to major changes in the water systems. For example, the tides disappeared, which resulted in a less smooth transition from sea water into fresh water. Flora and fauna suffered from this noticeable change.[8] In addition, rivers got covered up by polluted sludge, since there was no longer an open passage to the sea.

Project costs

The projects of the Delta Plan are financed with the Delta Fund. In 1958, when the Delta law was accepted under the Delta Works Commission, the total costs were estimated at 3.3 billion guilder. This was at that time equal to 20% of national GDP. This amount was spread out over the 25 years that it would take to complete the massive engineering project. The Delta works were mostly financed by the national budget, with a contribution of the Marshall Plan of 400 million guilder. In addition, the Dutch natural gas discovery contributed massively to the finance of the project. At completion in 1997, costs were set on 8.2 billion guilder.[9] Nevertheless, in 2012 the total costs were already set on around $13 billion.[10]

Current status

The original plan was completed by the Europoortkering which required the construction of the Maeslantkering in the Nieuwe Waterweg between Maassluis and Hook of Holland and the Hartelkering in the Hartel Canal near Spijkenisse. The works were declared finished after almost forty years in 1997.

Due to climate change and relative sea-level rise, the dikes will eventually have to be made higher and wider. This is a long term uphill battle against the sea. The needed level of flood protection and the resulting costs are a recurring subject of debate, and involve a complicated decision-making process. In 1995 it was agreed in the Delta Plan Large Rivers and Room for the River projects that about 500 kilometres of insufficient dyke revetments were reinforced and replaced along the Oosterschelde and Westerschelde between 1995 and 2015. After 2015, under the High Water Protection Program, additional upgrades are made.[11]

In September 2008, the Delta Commission presided by politician Cees Veerman advised in a report that the Netherlands would need a massive new building program to strengthen the country's water defenses against the anticipated effects of global warming for the next 190 years. The plans included drawing up worst-case scenarios for evacuations and included more than €100 billion, or $144 billion, in new spending through the year 2100 for measures, such as broadening coastal dunes and strengthening sea and river dikes. The commission said the country must plan for a rise in the North Sea of 1.3 meters by 2100 and 4 meters by 2200.[12]

Projects

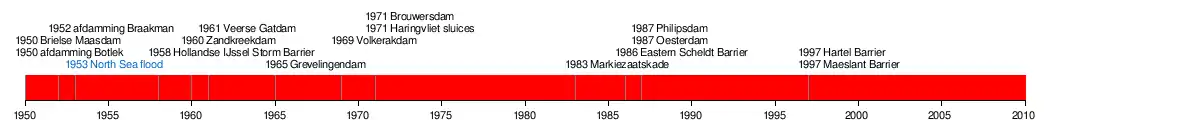

The works that are part of the Delta Works are listed in chronological order with their year of completion:

See also

References

- 1 2 Ley, Willy (October 1961). "The Home-Made Land". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 92–106.

- ↑ Kabat, Pavel; Fresco, Louise; Stive, Marcel J.F.; Veerman, Cees P.; van Alphen, Jos S.L.J.; Parmet, Bart W. A. H.; Hazeleger, Wilco; Katsman, Caroline A. (July 2009). "Dutch coasts in transition". Nature Geoscience. 2 (7): 450–451. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..450K. doi:10.1038/ngeo572.

- ↑ Deltares (2014). "Bouwen met de natuur in de praktijk". Delta Life. 1: 14–15.

- ↑ Van Buuren, A; Ellen, G.J.; Warner, J.F. (2016). "Path-dependency and policy learning in the Dutch delta: toward more resilient flood risk management in the Netherlands?". Ecology and Society. 21 (4). doi:10.5751/es-08765-210443.

- ↑ Rijcken, Ties (2015). "A critical approach to some new ideas about the Dutch flood risk system". Research in Urbanism Series. 3 (1).

- ↑ DGW. "Nationaal Waterplan". rijksoverheid.nl. Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu.

- ↑ d'Angremond, K (2003). "From disaster to Delta Project: the storm flood of 1953". Terra Aqua. 90 (3).

- ↑ de Vos, Art (2006). Nederland: een natte geschiedenis. Schiedam: Scriptum Publishers. p. 96. ISBN 90-5594-487-4.

- ↑ Aerts, J.C.J.H. (2009). Adaptation cost in the Netherlands: Climate Change and flood risk management. Climate Changes Spatial Planning and Knowledge for Climate. pp. 34–36. ISBN 9789088150159.

- ↑ Higgins, Andrew (15 November 2012). "Lessons for U.S. From a Flood-Prone Land". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ↑ Rijcken, T (2015). "A critical approach to some new ideas about the Dutch flood risk system". Research in Urbanism Series. 3 (1). doi:10.7480/rius.3.842. S2CID 110283338.

- ↑ "Dutch draw up drastic measures to defend coast against rising seas". The New York Times. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2010.