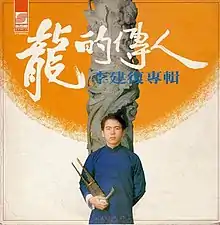

| "Descendants of the Dragon" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Lee Chien-Fu (Li Jianfu) | |

| from the album Descendants of the Dragon | |

| Released | 1980 |

| Genre | Campus folk song[1] |

| Label | 新格唱片,[2] later Rock Records |

| Songwriter(s) | Hou Dejian |

"Descendants of the Dragon" (simplified Chinese: 龙的传人; traditional Chinese: 龍的傳人; pinyin: lóng de chuán rén), also translated as "Heirs of the Dragon", is a Chinese song written by Hou Dejian. The song was first recorded and released by Lee Chien-Fu (simplified Chinese: 李建复; traditional Chinese: 李建復; pinyin: Lǐ Jiànfù), and Hou himself also recorded the song. It has been covered by other artists, including Lee's nephew Wang Leehom. The song became an anthem in the 1980s, and it is commonly regarded as a patriotic song that expresses sentiments of Chinese nationalism.

Background

The song was written in late 1978 by Taiwanese songwriter Hou Dejian while still a student, initially as a protest against United States' official diplomatic recognition of People's Republic of China, a decision first announced on December 15, 1978.[3] The song was first recorded by Lee Chien-Fu while he was a second-year university student in Taiwan.[4] The song was released in 1980 and became highly successful in Taiwan as a nationalistic anthem.[5] It stayed top in the list of the most popular songs of Minsheng newspaper for fifteen weeks.[6]

Hou later emigrated to mainland China in 1983, where the song also became popular, and it was interpreted as a pan-Chinese call for unification.[3] It became at one time the most popular pop song ever released in China.[7] Hou however was surprised that the song was used as an expression of pro-PRC sentiment, and said: "You have totally misread my intention!"[8] In 1989, Hou supported the students during the Tiananmen Square protests. The song became popular with the protesters, and it was adopted as an anthem for the movement together with "The Internationale" and Cui Jian's "I Have Nothing".[3][9]

Hou was later expelled from China for his support of the protests, his song was nevertheless praised for its expression of patriotism in China and continued to be used in state broadcast and official occasions.[10] The song was promoted by both the governments of Taiwan and mainland China.[11] It has been noted in its assertion of racial and cultural identity of Chineseness.[12][13]

Lyrics

The song states that China is the dragon, and Chinese people the "Descendants of the Dragon".[14] Although the use of Chinese dragon as a motif has a long history, using dragon to represent the Chinese people only became popular since the 1970s. During the pre-modern dynastic periods, the dragon was often associated with the rulers of China and used as a symbol of imperial rule, and there were strict stipulations on the use of the dragon by commoners since the Yuan dynasty.[13][15] Although the Qing government used the dragon as its imperial symbol on the flag of China, it was only during the early Republican era that the dragon began to be used to represent Chinese civilisation.[16]

The song begins by mentioning the great rivers of China, Yangtze and Yellow River, and that they are part of the cultural memories the songwriter. It relates that while the songwriter was born "under the feet of the dragon", he shares with the people of China the same genetic and cultural heritage and identity.[16] The original lyrics contain a reference to the Opium War,[3] and convey a sense of grievance against unnamed outside enemies.[11] Originally the lyrics described "Westerners" (洋人) as the enemy, but this was changed to "appeasers" (姑息) on publication.[17] The song ends by exhorting the "great dragon", i.e. China, to open its eyes to see and regain its greatness.[16]

Hou made two changes to the lyrics at a concert in Hong Kong in support of the students during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests: in the line "surrounded on all sides by the appeasers' swords" (四面楚歌是姑息的劍), "appeasers" (姑息) was replaced with "dictators" (獨裁); and the line "black hair, black eyes, yellow skin" (黑眼睛黑頭髮黃皮膚) was changed to "Whether you are willing or not" (不管你自己願不願意) to reflect the fact that not all Chinese people have such physical characteristics.[5]

Covers

A version of the song was recorded by Hong Kong singer Cheung Ming-man.[5]

Lee Chien-Fu's nephew Wang Leehom recorded a version of song in 2000, but modified the lyrics to add his parents' experience as immigrants in the US, which replaced the reference to the Opium War.[3] Wang said the song is the only Chinese pop song he heard while growing up in the States when his uncle Lee paid a visit in the 1980s and played the song.[18]

References

- ↑ Hui-Ching Chang; Richard Holt (20 November 2014). Language, Politics and Identity in Taiwan: Naming China. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-135-04635-4.

- ↑ "新格唱片出版目錄:1977~1986". Douban.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Philip V. Bohlman, ed. (December 2013). The Cambridge History of World Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86848-8.

- ↑ Chou, Oliver (11 November 2015). "Rallying cry of an oppressed nation: 1980s hit song still captures Chinese hearts 35 years on, Taiwanese singer Lee Chien-fu says". South China Morning Post.

- 1 2 3 "龍的傳人 Heirs of the Dragon". One Day in May.

- ↑ Hui-Ching Chang, Richard Holt (2006). "The Repositioning of "Taiwan" and "China": An Analysis of Patriotic Songs of Taiwan" (PDF). Intercultural Communication Studies. XV (1): 94–108.

- ↑ Barmé, Geremie (6 May 1999). In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-231-50245-0.

- ↑ Yiu Fai Chow; Jeroen de Kloet (5 November 2012). Sonic Multiplicities: Hong Kong Pop and the Global Circulation of Sound and Image. Intellect. p. 37). ISBN 978-1-84150-615-9.

- ↑ Donna Rouviere Anderson; Forrest Anderson. Silenced Scream: a Visual History of the 1989 Tiananmen Protests. Rouviere Media. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-61539-990-1.

- ↑ Dikötter, Frank (10 November 1997). The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-85065-287-8.

- 1 2 Guoguang Wu; Helen Lansdowne, eds. (6 November 2015). China's Transition from Communism – New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-50119-0.

- ↑ Yiu Fai Chow; Jeroen de Kloet (5 November 2012). Sonic Multiplicities: Hong Kong Pop and the Global Circulation of Sound and Image. Intellect. pp. 15–20. ISBN 978-1-84150-615-9.

- 1 2 Dikötter, Frank (10 November 1997). The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-85065-287-8.

- ↑ Guanjun Wu (21 May 2014). The Great Dragon Fantasy: A Lacanian Analysis of Contemporary Chinese Thought. WSPC. pp. 57–80. ISBN 978-981-4417-93-8.

- ↑ Richard R. Cook; David W. Pao (26 April 2012). After Imperialism: Christian Identity in China and the Global Evangelical Movement. James Clarke and Co Ltd. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-7188-9257-9.

- 1 2 3 Guanjun Wu (21 May 2014). The Great Dragon Fantasy: A Lacanian Analysis of Contemporary Chinese Thought. WSPC. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-981-4417-93-8.

- ↑ "龙的传人". shm.com.cn. 2009-06-23.

- ↑ Makinen, Julie (July 4, 2012). "Can Leehom Wang transcend China and America's pop cultures?". The Los Angeles Times.