A dewclaw is a digit– vestigial in some animals– on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digitigrade or unguligrade species, it does not make contact with the ground when the animal is standing. The name refers to the dewclaw's alleged tendency to brush dew away from grass.[1] On dogs and cats the dewclaws are on the inside of the front legs, similarly to a human's thumb, which shares evolutionary homology.[2] Although many animals have dewclaws, other similar species do not, such as horses, giraffes and the African wild dog.

Dogs

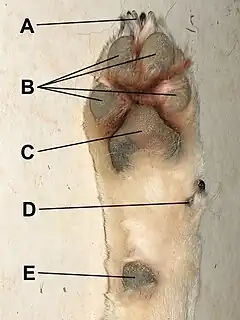

Dogs almost always have dewclaws on the inside of the front legs and occasionally also on the hind legs.[1][3] Unlike front dewclaws, rear dewclaws tend to have little bone or muscle structure in most breeds. It is normal, although not biologically necessary, that certain breeds will have more than one dewclaw on the same paw. At least one of these dewclaws will be poorly connected to the leg, and in this case it is often surgically removed. When a dog has extra dewclaws in addition to the usual one on each front leg, the dog is said to be double dewclawed. For certain dog breeds, a dewclaw is considered a necessity, e.g. a Beauceron for sheep herding and for navigating snowy terrain.[1] As such, there is some debate about whether a dewclaw helps dogs to gain traction when they run because in some dogs, the dewclaw makes contact when they are running and the nail on the dewclaw often wears down in the same way that the nails on their other toes do, from contact with the ground. In many dogs, the dewclaws never contact the ground. In this case, the dewclaw's nail never wears away, and it is often trimmed to maintain it at a safe length.

The dewclaws are not dead appendages. They can be used to lightly grip bones and other items that dogs hold with the paws. In some dogs, these claws may not appear to be connected to the leg at all except by a flap of skin; in such dogs, the claws do not have a use for gripping as the claw can easily fold or turn.[4]

Rear dewclaws

Canids have four claws on the rear feet,[5] although some domestic dog breeds or individuals have an additional claw, or more rarely two, as is the case with the beauceron. A more technical term for these additional digits on the rear legs is hind-limb-specific preaxial polydactyly.[6] Several genetic mechanisms can cause rear dewclaws; they involve the LMBR1 gene and related parts of the genome.[6] Rear dewclaws often have no phalanx bones and are attached by skin only.[7]

Dewclaw removal

There is some debate as to whether dewclaws should be surgically removed.[1][8][9] The argument for removal states that dewclaws are a weak digit, barely attached to the leg, and thus they can rip partway off or easily catch on something and break, which can be painful and prone to infection. Dewclaw removal is most easily performed when the dog is young, around 2–5 days of age. It can also be performed on older dogs if necessary though the surgery may be more difficult then. The surgery is fairly straightforward and may be done with local anesthetics if the digit is not well connected to the leg. Many dogs cannot resist licking the surgery site in the weeks following the procedure, so an Elizabethan collar or bitterant may be used to curtail this behavior, thus preventing infection.

Some pups are commonly sold by breeders "dew-clawed", that is with the dewclaws removed (as by a veterinarian) for perceived health and safety reasons. A few breed standards, such as that for Portuguese Water Dogs, also call for it.

Dewclaws and locomotion

Based on stop-action photographs, veterinarian M. Christine Zink of Johns Hopkins University believes that the entire front foot, including the dewclaws, contacts the ground while running. During running, the dewclaw digs into the ground preventing twisting or torque on the rest of the leg. Several tendons connect the front dewclaw to muscles in the lower leg, further demonstrating the front dewclaws' functionality. There are indications that dogs without dewclaws have more foot injuries and are more prone to arthritis. Zink recommends "for working dogs it is best for the dewclaws not to be amputated. If the dewclaw does suffer a traumatic injury, the problem can be dealt with at that time, including amputation if needed."[2]

Cats

Members of the cat family – including domestic cats[10] and wild cats like the lion[11] – have dewclaws. Generally a dewclaw grows on the inside of each front leg but not on either hind leg.[12]

The dewclaw on cats is not vestigial. Wild felids use the dewclaw in hunting, where it provides an additional claw with which to catch and hold prey.[11]

Hoofed animals

Hoofed animals walk on the tips of special toes, the hoofs. Cloven-hoofed animals walk on a central pair of hoofs, but many also have an outer pair of dewclaws on each foot. These are somewhat farther up the leg than the main hoofs, and similar in structure to them.[13] In some species (such as cattle) the dewclaws are much smaller than the hoofs and never touch the ground. In others (such as pigs and many deer), they are only a little smaller than the hoofs, and may reach the ground in soft conditions or when jumping. Some hoofed animals (such as giraffes and modern horses) have no dewclaws. Video evidence suggests some animals use dewclaws in grooming or scratching themselves or to have better grasp during mating.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Danziger, D., & McCrum, M. (2008). The Thingummy: A book about those everyday objects you just can't name. London: Doubleday.

- 1 2 Zink, M. Christine. "Form Follows Function – A New Perspective on an Old Adage" (PDF). Penn Vet Working Dog Center. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Rice, Dan (2008). The Complete Book of Dog Breeding (2 ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7641-3887-4.

- ↑ Hoskins, Johnny D. (2001). Veterinary Pediatrics: Dogs and Cats from Birth to Six Months (3 ed.). Saunders. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-7216-7665-4.

- ↑ Macdonald, D. (1984). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 56. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- 1 2 Park, K.; Kang, J.; Subedi, K. P.; Ha, J-H.; Park, C. (August 2008). "Canine Polydactyl Mutations With Heterogeneous Origin in the Conserved Intronic Sequence of LMBR1". Genetics. 179 (4): 2163–2172. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.087114. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 2516088. PMID 18689889.

- ↑ Hosgood, Giselle (1998). Small Animal Paediatric Medicine and Surgery. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7506-3599-8.

- ↑ Lotz, Kristina N. "The Dewclaws Debate – Keep Them or Lose Them?". iheartdogs.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Dog Dew Claw Removal". vetinfo.com. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Clipping a Cat's Claws (Toenails)". Pet Health Topics. Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

Cats have a nail on the inner side of each foot called the dew claw. Remember to trim these as they are not worn down when the cat scratches and can grow in a circle, growing into the foot.

- 1 2 "Physiology". Lion ALERT. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

Lions have four claws on their back feet but five on the front where the dew claw is found. This acts like a thumb and is used to hold down prey while the jaws rip away the meat from bone. Set well back from the other claws the dew claw does not appear in the print.

- ↑ Bircher, Steve (5 November 2011), Tiger Tales (PDF), National Tiger Sanctuary, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013

- ↑ Perich, Shawn; Furman, Michael (2003). Whitetail Hunting: Top-notch Strategies for Hunting North America's Most Popular Big-Game Animal. Creative Publishing international. pp. 8, 9. ISBN 978-1-58923-129-0.