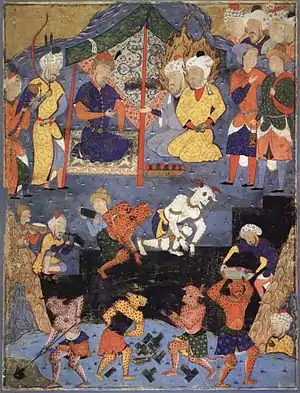

Dhu al-Qarnayn, (Arabic: ذُو ٱلْقَرْنَيْن, romanized: Ḏū l-Qarnayn, IPA: [ðuː‿l.qarˈnajn]; lit. "The Two-Horned One") appears in the Quran, Surah al-Kahf (18), Ayahs 83–101 as one who travels to east and west and sets up a barrier between a certain people and Gog and Magog (Arabic: يَأْجُوجُ وَمَأْجُوجُ, romanized: Yaʾjūj wa-Maʾjūj).[1] Elsewhere, the Quran tells how the end of the world will be signaled by the release of Gog and Magog from behind the barrier. Other apocalyptic writings predict that their destruction by God in a single night will usher in the Day of Resurrection (Yawm al-Qiyāmah).[2]

The majority of modern scholars and Islamic commentators identify Dhu al-Qarnayn with Alexander the Great,[3] although many medieval scholars disputed that identification, such as al-Maqrizi.[4] Early Muslim commentators and historians variously identified Dhu al-Qarnayn,[5] most notably as Alexander the Great and as the South Arabian Himyarite king al-Ṣaʿb bin Dhī Marāthid.[6] Some modern scholars have argued that the origin of the Quranic story may be found in the Syriac Alexander Legend,[7] but others disagree.[8][9]

Quran 18:83-101

The story of Dhu al-Qarnayn is related in Surah 18 of the Quran, al-Kahf ("The Cave") revealed to Muhammad when his tribe, Quraysh, sent two men to discover whether the Jews, with their superior knowledge of the scriptures, could advise them on whether Muhammad was a true prophet of God. The rabbis told them to ask Muhammad about three things, one of them "about a man who travelled and reached the east and the west of the earth, what was his story". "If he tells you about these things, then he is a prophet, so follow him, but if he does not tell you, then he is a man who is making things up, so deal with him as you see fit." (Verses 18:83-98)[10]

The verses of the chapter reproduced below show Dhu al-Qarnayn traveling first to the Western limit of travel where he sees the sun set in a muddy spring, then to the furthest East where he sees it rise from the ocean, and finally northward to a place in the mountains where he finds a people oppressed by Gog and Magog:

| Verse Number | Arabic (Uthmani script) | Talal Itani |

|---|---|---|

| 18:83 | وَيَسْـَٔلُونَكَ عَن ذِى ٱلْقَرْنَيْنِ ۖ قُلْ سَأَتْلُوا۟ عَلَيْكُم مِّنْهُ ذِكْرًا | And they ask you about Zul-Qarnain. Say, “I will tell you something about him.” |

| 18:84 | إِنَّا مَكَّنَّا لَهُۥ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ وَءَاتَيْنَٰهُ مِن كُلِّ شَىْءٍ سَبَبًا | We established him on earth, and gave him all kinds of means. |

| 18:85 | فَأَتْبَعَ سَبَبًا | He pursued a certain course. |

| 18:86 | حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا بَلَغَ مَغْرِبَ ٱلشَّمْسِ وَجَدَهَا تَغْرُبُ فِى عَيْنٍ حَمِئَةٍ وَوَجَدَ عِندَهَا قَوْمًا ۗ قُلْنَا يَٰذَا ٱلْقَرْنَيْنِ إِمَّآ أَن تُعَذِّبَ وَإِمَّآ أَن تَتَّخِذَ فِيهِمْ حُسْنًا | Until, when he reached the setting of the sun, he found it setting in a murky spring, and found a people in its vicinity. We said, “O Zul-Qarnain, you may either inflict a penalty, or else treat them kindly.” |

| 18:87 | قَالَ أَمَّا مَن ظَلَمَ فَسَوْفَ نُعَذِّبُهُۥ ثُمَّ يُرَدُّ إِلَىٰ رَبِّهِۦ فَيُعَذِّبُهُۥ عَذَابًا نُّكْرًا | He said, “As for him who does wrong, we will penalize him, then he will be returned to his Lord, and He will punish him with an unheard-of torment. |

| 18:88 | وَأَمَّا مَنْ ءَامَنَ وَعَمِلَ صَٰلِحًا فَلَهُۥ جَزَآءً ٱلْحُسْنَىٰ ۖ وَسَنَقُولُ لَهُۥ مِنْ أَمْرِنَا يُسْرًا | “But as for him who believes and acts righteously, he will have the finest reward, and We will speak to him of Our command with ease.” |

| 18:89 | ثُمَّ أَتْبَعَ سَبَبًا | Then he pursued a course. |

| 18:90 | حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا بَلَغَ مَطْلِعَ ٱلشَّمْسِ وَجَدَهَا تَطْلُعُ عَلَىٰ قَوْمٍ لَّمْ نَجْعَل لَّهُم مِّن دُونِهَا سِتْرًا | Until, when he reached the rising of the sun, he found it rising on a people for whom We had provided no shelter from it. |

| 18:91 | كَذَٰلِكَ وَقَدْ أَحَطْنَا بِمَا لَدَيْهِ خُبْرًا | And so it was. We had full knowledge of what he had. |

| 18:92 | ثُمَّ أَتْبَعَ سَبَبًا | Then he pursued a course. |

| 18:93 | حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا بَلَغَ بَيْنَ ٱلسَّدَّيْنِ وَجَدَ مِن دُونِهِمَا قَوْمًا لَّا يَكَادُونَ يَفْقَهُونَ قَوْلًا | Until, when he reached the point separating the two barriers, he found beside them a people who could barely understand what is said. |

| 18:94 | قَالُوا۟ يَٰذَا ٱلْقَرْنَيْنِ إِنَّ يَأْجُوجَ وَمَأْجُوجَ مُفْسِدُونَ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ فَهَلْ نَجْعَلُ لَكَ خَرْجًا عَلَىٰٓ أَن تَجْعَلَ بَيْنَنَا وَبَيْنَهُمْ سَدًّا | They said, “O Zul-Qarnain, the Gog and Magog are spreading chaos in the land. Can we pay you, to build between us and them a wall?” |

| 18:95 | قَالَ مَا مَكَّنِّى فِيهِ رَبِّى خَيْرٌ فَأَعِينُونِى بِقُوَّةٍ أَجْعَلْ بَيْنَكُمْ وَبَيْنَهُمْ رَدْمًا | He said, “What my Lord has empowered me with is better. But assist me with strength, and I will build between you and them a dam.” |

| 18:96 | ءَاتُونِى زُبَرَ ٱلْحَدِيدِ ۖ حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا سَاوَىٰ بَيْنَ ٱلصَّدَفَيْنِ قَالَ ٱنفُخُوا۟ ۖ حَتَّىٰٓ إِذَا جَعَلَهُۥ نَارًا قَالَ ءَاتُونِىٓ أُفْرِغْ عَلَيْهِ قِطْرًا | “Bring me blocks of iron.” So that, when he had leveled up between the two cliffs, he said, “Blow.” And having turned it into a fire, he said, “Bring me tar to pour over it.” |

| 18:97 | فَمَا ٱسْطَٰعُوٓا۟ أَن يَظْهَرُوهُ وَمَا ٱسْتَطَٰعُوا۟ لَهُۥ نَقْبًا | So they were unable to climb it, and they could not penetrate it. |

| 18:98 | قَالَ هَٰذَا رَحْمَةٌ مِّن رَّبِّى ۖ فَإِذَا جَآءَ وَعْدُ رَبِّى جَعَلَهُۥ دَكَّآءَ ۖ وَكَانَ وَعْدُ رَبِّى حَقًّا | He said, “This is a mercy from my Lord. But when the promise of my Lord comes true, He will turn it into rubble, and the promise of my Lord is always true.” |

| 18:99 | وَتَرَكْنَا بَعْضَهُمْ يَوْمَئِذٍ يَمُوجُ فِى بَعْضٍ ۖ وَنُفِخَ فِى ٱلصُّورِ فَجَمَعْنَٰهُمْ جَمْعًا | On that Day, We will leave them surging upon one another. And the Trumpet will be blown, and We will gather them together. |

| 18:100 | وَعَرَضْنَا جَهَنَّمَ يَوْمَئِذٍ لِّلْكَٰفِرِينَ عَرْضًا | On that Day, We will present the disbelievers to Hell, all displayed. |

| 18:101 | ٱلَّذِينَ كَانَتْ أَعْيُنُهُمْ فِى غِطَآءٍ عَن ذِكْرِى وَكَانُوا۟ لَا يَسْتَطِيعُونَ سَمْعًا | Those whose eyes were screened to My message, and were unable to hear. |

Later literature

Dhu al-Qarnayn the traveller was a favourite subject for later writers. In one of many Arabic and Persian versions of the meeting of Alexander with the Indian sages, the Persian Sunni Sufi and theologian al-Ghazali (1058–1111) wrote how Dhu al-Qarnayn came across a people who had no possessions but dug graves at the doors of their houses; their king explained that they did this because the only certainty in life is death. Ghazali's version later made its way into the One Thousand and One Nights.[11]

The Sufi poet Rumi (1207-1273), perhaps the most famous of medieval Persian poets, described Dhu al-Qarnayn's eastern journey. The hero ascends Mount Qaf, the "mother" of all other mountains, which is made of emerald and forms a ring encircling the entire Earth, with veins under every land. At Dhu al-Qarnayn's request the mountain explains the origin of earthquakes: when God wills, the mountain causes one of its veins to throb, and thus an earthquake results. Elsewhere on the great mountain Dhu al-Qarnayn meets Israfil (the archangel Raphael), standing ready to blow the trumpet on the Day of Judgement.[12]

The Malay language Hikayat Iskandar Zulkarnain traces the ancestry of several Southeast Asian royal families, such as the royalty of the Minangkabau of Central Sumatra,[13] from Iskandar Zulkarnain,[14] through the Cholan emperor Rajendra I in the Malay Annals.[15][16][17]

People identified as Dhu al-Qarnayn

Alexander the Great

According to some historians, the story of Dhu al-Qarnayn has its origins in legends of Alexander the Great current in the Middle East, namely the Syriac Alexander Legend but this thesis has been refuted several times by other historians and Muslim scholars. The Scythians, the descendants of Magog, once defeated one of Alexander's generals, upon which Alexander built a wall in the Caucasus Mountains to keep them out of civilised lands; the basic elements are found in the works of Josephus. The legend went through much further elaboration in subsequent centuries before eventually finding its way into the Quran through a Syrian version.[18] However, the supposed influence of the Syriac Legend on the Quran has been questioned based on dating inconsistencies and missing key motifs.[19][9]

While the Syriac Alexander Legend references the horns of Alexander, it consistently refers to the hero by his Greek name, not using a variant epithet.[20] The use of the Islamic epithet Dhu al-Qarnayn "Two-Horned", first occurred in the Quran.[21] The reasons behind the name "Two-Horned" are somewhat obscure: the scholar al-Tabari (839-923 CE) held it was because he went from one extremity ("horn") of the world to the other,[22] but it may ultimately derive from the image of Alexander wearing the horns of the ram-god Zeus-Ammon, as popularised on coins throughout the Hellenistic Near East.[23]

The wall Dhu al-Qarnayn builds on his northern journey may have reflected a distant knowledge of the Great Wall of China (the 12th-century scholar Muhammad al-Idrisi drew a map for Roger II of Sicily showing the "Land of Gog and Magog" in Mongolia), or of various Sasanian walls built in the Caspian Sea region against the northern barbarians, or a conflation of the two.[24]

Dhu al-Qarnayn also journeys to the western and eastern extremities ("qarns", tips) of the Earth.[25] Ernst claims that Dhu al-Qarnayn finding the sun setting in a "muddy spring" in the West is equivalent to the "poisonous sea" found by Alexander in the Syriac legend. In the Syriac story Alexander tested the sea by sending condemned prisoners into it, while the Quran refers to this as a administration of justice. In the East both the Syrian legend and the Quran, according to Ernst, have Alexander/Dhu al-Qarnayn find a people who live so close to the rising sun that they have no protection from its heat.[26]

The 16th-century diplomat and author Leo Africanus believed Alexander to have appeared in the Qur'an as Dhu al-Qarnayn.[27]

Since Dhu al-Qarnayn is said to have lived near the time of Abraham, several medieval exegetes and historians did not identify him with Alexander to avoid the chronological discrepancy.[28] Other notable Muslim commentators, including ibn Kathir,[29]:100-101 ibn Taymiyyah,[29]:101[30] and Naser Makarem Shirazi,[31] have also used theological arguments to reject the Alexander identification: Alexander lived only a short time whereas Dhu al-Qarnayn (according to some traditions) lived for 700 years as a sign of God's blessing, though this is not mentioned in the Quran, and Dhu al-Qarnayn worshipped only one God, while Alexander was a polytheist.[32]

King Ṣaʿb Dhu-Marāthid

The various campaigns of Dhu al-Qarnayn mentioned in Q:18:83-101 have also been attributed to the South Arabian Himyarite king Ṣaʿb Dhu-Marāthid (also known as al-Rāʾid).[33][34] According to Wahb ibn Munabbih, as quoted by ibn Hisham,[35] King Ṣaʿb was a conqueror who was given the epithet Dhu al-Qarnayn after meeting the Khidr in Jerusalem. He then travels to the ends of the earth, conquering or converting people until being led by the Khidr through the Land of Darkness.[36] According to Wheeler, it is possible that some elements of these accounts that were originally associated with Ṣaʿb have been incorporated into stories which identify Dhu al-Qarnayn with Alexander.[37]

Cyrus the Great

In modern times, some Muslim scholars have argued in favour of Dhu al-Qarnayn being actually Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire and conqueror of Persia and Babylon. Proponents of this view cite Daniel's vision in the Old Testament where he saw a two-horned ram that represents "the kings of Media and Persia" (Daniel 8:20).[36]

Archeological evidence cited includes the Cyrus Cylinder, which portrays Cyrus as a worshipper of the Babylonian god Marduk, who ordered him to rule the world and establish justice in Babylon. The cylinder states that idols that Nabonidus had brought to Babylon from various other Babylonian cities were reinstalled by Cyrus in their former sanctuaries and ruined temples reconstructed. Supported with other texts and inscriptions, Cyrus appears to have initiated a general policy of permitting religious freedom throughout his domains.[38][39][40]

A famous relief on a palace doorway pillar in Pasagardae depicts a winged figure wearing a Hemhem crown (a type of ancient Egyptian crown mounted on a pair of long spiral ram's horns). Some scholars take this to be a depiction of Cyrus due to an inscription that was once located above it,[41][42] though most see it as a tutelary genie, or protective figure and note that the same inscription was also written on other palaces in the complex.[43][44][45]

This theory was proposed in 1855 by the German philologist G. M. Redslob, but it did not gain followers in the west.[46] Among Muslim commentators, it was first promoted by Sayyed Ahmad Khan (d. 1889),[40] then by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad,[31][47] and generated wider acceptance over the years.[48] Wheeler accepts the possibility but points out the absence of such a theory by classical Muslim commentators.[36]

Others

Other persons who either were identified with the Quranic figure or given the title Dhu al-Qarnayn:

- Afrīqish al-Ḥimyarī, king of Himyar. Al-Biruni in his book, The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries, listed a number of figures whom people thought to be Dhu al-Qarnayn. He favoured the opinion that Dhu al-Qarnayn was the Yamani prince Afrīqish, who conquered the Mediterranean and established a city called Afrīqiah. He was called Dhu al-Qarnayn because he ruled the lands of the rising and setting sun. To support his argument, al-Biruni cited Arabic onomastics, noting that compound names beginning with Dhū, such as Dhū Nuwās and Dhū Yazan, were common among the kings of Himyar.[49]

- Fereydun. According to al-Tabari's Tarikh, some say Dhu al-Qarnayn the Elder (al-akbar), who lived in the era of Abraham, was the mythical Persian king Fereydun, who al-Tabari rendered as Afrīdhūn ibn Athfiyān.[50]

- In an account attributed to Umar bin Khattab, Dhu al-Qarnayn is said to be an angel or part angel.[51]

- Imru'l-Qays (died 328 CE), a prince of the Lakhmids of southern Mesopotamia, an ally first of Persia and then of Rome, celebrated in romance for his exploits.[52]

- Messiah ben Joseph, a fabulous military saviour expected by Yemenite Jews.[53]

- Darius the Great.[54]

- Kisrounis, Parthian king.[55][5]

See also

References

- ↑ Netton 2006, p. 72.

- ↑ Cook 2005, p. 8,10.

- ↑ Watt 1960–2007: "It is generally agreed both by Muslim commentators and modéra [sic] occidental scholars that Dhu ’l-Ḳarnayn [...] is to be identified with Alexander the Great." Cook 2013: "[...] Dhū al-Qarnayn (usually identified with Alexander the Great) [...]".

- ↑ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (17 April 2018). Khwadāynāmag The Middle Persian Book of Kings. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27764-9.

Many Mediaeval scholars argued against the identification, though. Cf., e.g., the discussion in al-Maqrizi, Khabar §§212-232.

- 1 2 Emily Cottrell. "An Early Mirror for Princes and Manual for Secretaries: The Epistolary Novel of Aristotle and Alexander". In Krzysztof Nawotka (ed.). Alexander the Great and the East: History, Art, Tradition. p. 323).

- ↑ Zadeh, Travis (28 February 2017). Mapping Frontiers Across Medieval Islam: Geography, Translation and the 'Abbasid Empire. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-78673-131-9.

In the early history of Islam there was a lively debate over the true identity of Dhū 'l-Qarnayn. One prominent identification was with an ancient South Arabian Ḥimyarī king, generally referred to in the sources as al-Ṣaʿb b. Dhī Marāthid. [...] Indeed the association of Dhū 'l-Qarnayn with the South Arabian ruler can be traced in many early Arabic sources.

- ↑ Van Bladel, Kevin (2008). "The Alexander Legend in the Qur'an 18:83-102". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʼān in Its Historical Context. Routledge.

- ↑ Faustina Doufikar-Aerts (2016). "Coptic Miniature Painting in the Arabic Alexander Romance". Alexander the Great in the Middle Ages: Transcultural Perspectives. University of Toronto Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4426-4466-3.

The essence of his theory is that parallels can be found in the Quranic verses on Dhu'l-qarnayn (18:82-9) and the Christian Syriac Alexander Legend. The hypothesis requires a revision, because Noldeke's dating of Jacob of Sarug's Homily and the Christian Syriac Alexander Legend is no longer valid; therefore, it does not need to be rejected, but it has to be viewed from another perspective. See my exposé in Alexander Magnus Arabicus (see note 7), chapter 3.3 and note 57.

- 1 2 Klar, Marianna (2020). "Qur'anic Exempla and Late Antique Narratives". The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies (PDF). p. 134.

The Qur'anic exemplum is highly allusive, and makes no reference to vast tracts of the narrative line attested in the Neṣḥānā. Where the two sources would appear to utilize the same motif, there are substantial differences to the way these motifs are framed. These differences are sometimes so significant as to suggest that the motifs might not, in fact, be comparable at all.

- ↑ Itani, Talal. Quran in English - Clear and Easy to Read.

- ↑ Yamanaka & Nishio 2006, p. 103-105.

- ↑ Berberian 2014, p. 118-119.

- ↑ Early Modern History ISBN 981-3018-28-3 page 60

- ↑ Balai Seni Lukis Negara (Malaysia) (1999). Seni dan nasionalisme: dulu & kini. Balai Seni Lukis Negara. ISBN 9789839572278.

- ↑ S. Amran Tasai; Djamari; Budiono Isas (2005). Sejarah Melayu: sebagai karya sastra dan karya sejarah : sebuah antologi. Pusat Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional. p. 67. ISBN 978-979-685-524-7.

- ↑ Radzi Sapiee (2007). Berpetualang Ke Aceh: Membela Syiar Asal. Wasilah Merah Silu Enterprise. p. 69. ISBN 978-983-42031-1-5.

- ↑ Dewan bahasa. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1980. pp. 333, 486.

- ↑ Bietenholz 1994, p. 122-123.

- ↑ Wheeler 1998, p. 201: "There are a number of problems with the dating of the Syriac versions and their supposed influence on the Qurʾan and later Alexander stories, not the least of which is the confusion of what has been called the Syriac Pseudo-Callisthenes, the sermon of Jacob of Serugh, and the so-called Syriac Legend of Alexander. Second, the key elements of Q 18:60-65, 18:83-102, and the story of Ibn Hishām's Saʿb dhu al-Qarnayn do not occur in the Syriac Pseudo-Callisthenes."

- ↑ Zadeh, Travis (28 February 2017). Mapping Frontiers Across Medieval Islam: Geography, Translation and the 'Abbasid Empire. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-78673-131-9.

- ↑ Faustina Doufikar-Aerts (2016). "Coptic Miniature Painting in the Arabic Alexander Romance". Alexander the Great in the Middle Ages: Transcultural Perspectives. University of Toronto Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4426-4466-3.

- ↑ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 57 fn.3.

- ↑ Pinault 1992, p. 181 fn.71.

- ↑ Glassé & Smith 2003, p. 39.

- ↑ Wheeler 2013, p. 96.

- ↑ Ernst 2011, p. 133.

- ↑ Hernández, Cándida Ferrero; Tolan, John (25 October 2021). The Latin Qur’an, 1143–1500: Translation, Transition, Interpretation. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 309. ISBN 978-3-11-070271-2.

- ↑ Rubanovich, Julia (10 October 2016). "A Hero Without Borders: Alexander the Great in the Medieval Persian Tradition". Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond. BRILL. p. 211. ISBN 978-90-04-30772-8.

- 1 2 Seoharwi, Muhammad Hifzur Rahman. Qasas-ul-Qur'an. Vol. 3.

- ↑ Ibn Taymiyyah. الفرقان - بین اولیاء الرحمٰن و اولیاء الشیطٰن [The Criterion - Between Allies of the Merciful & The Allies of the Devil] (PDF). Translated by Ibn Morgan, Salim Adballah. Idara Ahya-us-Sunnah. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- 1 2 Shirazi, Naser Makarem. Tafseer-e-Namoona.

- ↑ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 57 fn.2.

- ↑ Wheeler 1998, pp. 200–1.

- ↑ Canova, Giovvani (1998). "Alexander Romance". In Meisami, Julie Scott (ed.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Taylor & Francis. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-415-18571-4.

- ↑

Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: Account of Sa'b dhu al-Qarnayn

Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: Account of Sa'b dhu al-Qarnayn - 1 2 3 Wheeler 1998, p. 200.

- ↑ Wheeler 1998, p. 201.

- ↑ "CYRUS iii. Cyrus II The Great". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ Simonin, Antoine (2012). "The Cyrus Cylinder". worldhistory.org. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- 1 2 Merhavy, Menahem (2015). "Religious Appropriation of National Symbols in Iran: Searching for Cyrus the Great". Iranian Studies. 48 (6): 933–948. doi:10.1080/00210862.2014.922277. S2CID 144725336.

- ↑ Macuch, Rudolf (1991). "Pseudo-Callisthenes Orientalis and the Problem of Dhu l-qarnain". Graeco-Arabica, IV: 223–264.

On ancient coins, he was represented as Jupiter Ammon Alexander with a horn in profile so that the imagination of two horns was incorporated in this picture. But this representation of mighty kings is much more ancient than Alexander, as is proved by the relief of Cyrus. (p.263)

- ↑ Daneshgar 2016, p. 222.

- ↑ Curzon, George Nathaniel (2018). Persia and the Persian Question. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-108-08085-9.

- ↑ Stronach, David (2009). "PASARGADAE". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ Stronach, David (2003). "HERZFELD, ERNST ii. HERZFELD AND PASARGADAE". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ Tatum, James (1994). The Search for the ancient novel. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-8018-4619-9.

- ↑ Pirzada, Shams. Dawat ul Quran. p. 985.

- ↑ Maududi, Syed Abul Ala. Tafhim al-Qur'an.

The identification ... has been a controversial matter from the earliest times. In general the commentators have been of the opinion that he was Alexander the Great but the characteristics of Zul-Qarnain described in the Qur'an are not applicable to him. However, now the commentators are inclined to believe that Zul-Qarnain was Cyrus ... We are also of the opinion that probably Zul-Qarnain was Cyrus...

- ↑ Daneshgar 2016, p. 226.

- ↑ Brinner, William, ed. (1991). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume III: The Children of Israel. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7914-0687-8.

- ↑ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (31 October 2022). Al-Maqrīzī's al-Ḫabar ʿan al-bašar: Vol. V, Section 4: Persia and Its Kings, Part II. BRILL. p. 287. ISBN 978-90-04-52876-5.

- ↑ Ball 2002, p. 97-98.

- ↑ Wasserstrom 2014, p. 61-62.

- ↑ Pearls from Surah Al-Kahf: Exploring the Qur'an's Meaning, Yasir Qadhi Kube Publishing Limited, 4 Mar 2020, ISBN 9781847741318

- ↑ Agapius, Kitab al-'Unvan [Universal History], p. 653

Sources

- Ball, Warwick (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781134823871.

- Berberian, Manuel (2014). Earthquakes and Coseismic Surface Faulting on the Iranian Plateau. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0444632975.

- Bietenholz, Peter G. (1994). Historia and fabula: myths and legends in historical thought from antiquity to the modern age. Brill. ISBN 978-9004100633.

- Cook, David B. (2005). Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630586.

- Cook, David B. (2013). "Gog and Magog". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27495.

- Ernst, Carl W. (2011). How to Read the Qur'an: A New Guide, with Select Translations. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781134823871.

- Glassé, Cyril; Smith, Huston (2003). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759101906.

- Netton, Ian Richard (2006). A Popular Dictionary of Islam. Routledge. ISBN 9781135797737.

- Pinault, David (1992). Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004095304.

- Van Donzel, Emeri J.; Schmidt, Andrea Barbara (2010). Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources. Brill. ISBN 978-9004174160.

- Wasserstrom, Steven M. (2014). Between Muslim and Jew: The Problem of Symbiosis Under Early Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400864133.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1960–2007). "al-Iskandar". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3630.

- Wheeler, Brannon M. (1998). "Moses or Alexander? Early Islamic Exegesis of Qurʾān 18:60-65". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 57 (3): 191–215. doi:10.1086/468638. S2CID 162366963.

- Wheeler, Brannon M. (2013). Moses in the Qur'an and Islamic Exegesis. Routledge. ISBN 9781136128905.

- Yamanaka, Yuriko; Nishio, Tetsuo (2006). The Arabian Nights and Orientalism: Perspectives from East and West. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850437680.

- Daneshgar, Majid (10 June 2016). "Dhū l-Qarnayn in modern Malay commentaries". In Daneshgar, Majid; Riddell, Peter G.; Rippin, Andrew (eds.). The Qur'an in the Malay-Indonesian World: Context and Interpretation. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-29476-4.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2008). "The Alexander Legend in the Qur'an 18:83-102". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʼān in Its Historical Context. Routledge.

Further reading

- Soomro, Taha (2020), Did the Qurʾān borrow from the Syriac Legend of Alexander?