| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Acetic peroxyanhydride[1] | |

| Other names

acetyl peroxide (2:1); diacetyl peroxide; Peroxide, diacetyl; ethanoyl peroxide; acetyl ethaneperoxoate; ethanoyl ethane peroxoate;[2] peracetic acid acetyl ester | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.409 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2084 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H6O4 | |

| Molar mass | 118.088 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless crystals[3] |

| Density | 1.163 g/cm3[3] |

| Melting point | 30 °C (86 °F; 303 K) |

| Boiling point | 121.4 °C (250.5 °F; 394.5 K) at 760 mmHg; 63 °C (145 °F; 336 K) at 21 mmHg[4] |

| slight in cold water [3] | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Explosive, oxidizer |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 32.2 °C (90.0 °F; 305.3 K) (45 °C [113 °F; 318 K][5]) |

| Explosive data | |

| Shock sensitivity | Very high / moderate when wet |

| Friction sensitivity | Very high / moderate when wet |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

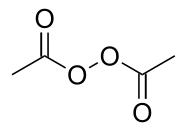

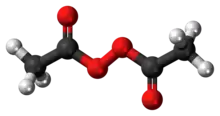

Diacetyl peroxide is the organic peroxide with the formula (CH3CO2)2. It is a white solid or oily liquid with a sharp odor.[5] As with a number of organic peroxides, it is explosive.[6] It is often used as a solution, e.g., in dimethyl phthalate.[3]

History

Diacetyl peroxide was discovered in 1858 by Benjamin Collins Brodie,[7] who obtained the compound by treating glacial acetic acid with barium peroxide in anhydrous diethyl ether.[8]

Preparation

Diacetyl peroxide forms upon combining hydrogen peroxide and excess acetic anhydride. Peracetic acid is an intermediate.[9]

Safety

Consisting of both an oxidizer, the O-O bond and reducing agents, the C-C and C-H bonds, diacetyl peroxide is shock sensitive and explosive.[10][11][3]

The threshold quantity for Process Safety Management per Occupational Safety and Health Administration 1910.119 is 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) if the concentration of the diacetyl peroxide solution is greater than 70%.[12]

There have been reports of detonation of the pure material. The 25% solution also has explosive potential.[13] The crystalline peroxide is especially shock sensitive and a high explosion risk.[14][11]

Safety

Organic peroxides are all prone to exothermic decomposition, potentially leading to explosions and fire.[15]

Contact with liquid causes irritation of eyes and skin. If ingested, it irritates mouth and stomach.[16][17][18][19]

References

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 829. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ↑ Diacetyl peroxide

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis, R. J., Sr, ed. (1997). Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary (13th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. p. 13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ Lide, D. R., ed. (1998–1999). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (79th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 3–250.

- 1 2 "Acetyl peroxide" (PDF). NJ.gov.

- ↑ Sax, N. I. (1975). Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials (4th ed.). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 357. ISBN 9780442273682.

- ↑ "Anniversary Meeting". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 39: 177–201. 30 March 1881. doi:10.1039/CT8813900177. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ↑ Brodie, Benjamin Collins (1 January 1859). "I. Note on the formation of the peroxides of the radicals of the organic acids". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 9: 361–365. doi:10.1098/rspl.1857.0087. S2CID 97728118.

- ↑ "Chemical Safety: Synthesis Procedure". Chemical & Engineering News. 89 (2): 2. 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Chemical Safety: Synthesis Procedure". Chemical & Engineering News. 89 (2): 2. 2011-01-10.

- 1 2 National Fire Protection Association (1978). Fire Protection Guide on Hazardous Materials (7th ed.). Boston, MA: National Fire Protection Association. pp. 49–110.

- ↑ "1910.119 App A - List of Highly Hazardous Chemicals, Toxics and Reactives (Mandatory) | Occupational Safety and Health Administration".

- ↑ National Research Council (1981). Prudent Practices for Handling Hazardous Chemicals in Laboratories. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. p. 106.

- ↑ Bretherick, L. (1990). Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 453, 1104.

- ↑ Klenk, Herbert; Götz, Peter H.; Siegmeier, Rainer; Mayr, Wilfried. "Peroxy Compounds, Organic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_199.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ National Research Council (1981). Prudent Practices for Handling Hazardous Chemicals in Laboratories. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. p. 106.

- ↑ International Labour Office (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. Vol. 1–4 (4th ed.). Geneva: International Labour Office. p. 104.349.

- ↑ Clayton, G.D.; Clayton, F.E., eds. (1993–1994). Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. Vol. 2A–2F (4th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. p. 545.

- ↑ Mackison, F. W.; Stricoff, R. S.; Partridge, L. J., Jr, eds. (Jan 1981). NIOSH/OSHA - Occupational Health Guidelines for Chemical Hazards. DHHS(NIOSH) Publication No. 81–123. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- "Peroxide, diacetyl (C4H6O4)". Landolt-Boernstein Substance/Property Index.

- "Zuordnung der Organischen Peroxide zu Gefahrgruppen nach § 3 Abs. 1". Berufsgenossenschaft Handel und Warendistribution (in German). Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-12-22.