| Dickenson Road Studios | |

|---|---|

BBC Dickenson Road Studios pictured c. 1965 | |

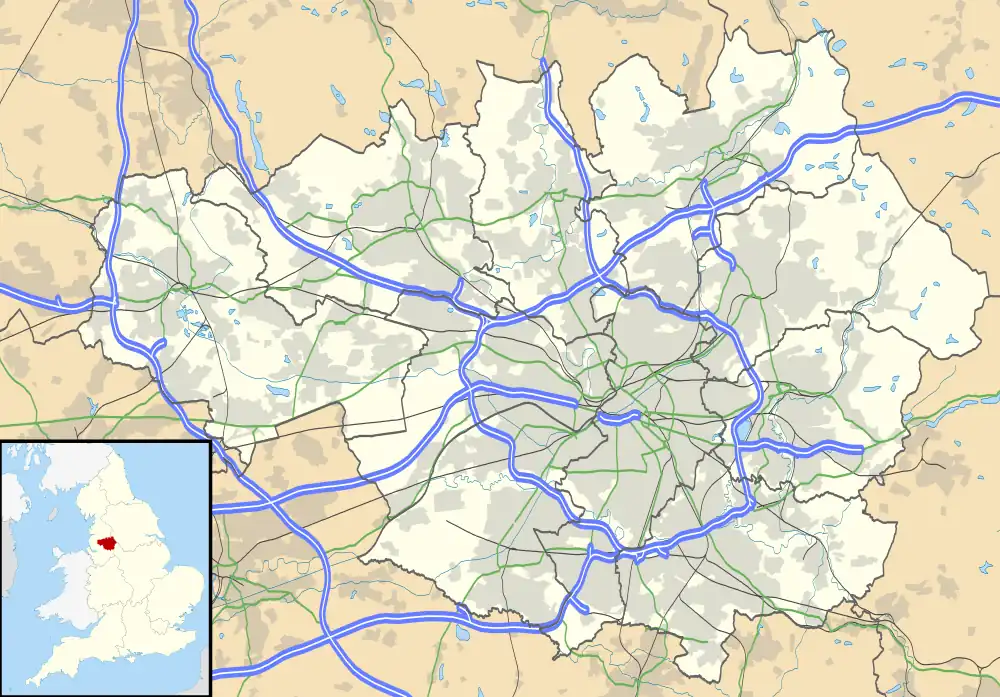

Dickenson Road Studios Location in Greater Manchester  Dickenson Road Studios Location in the City of Manchester | |

| Former names | Dickenson Rd Wesleyan Methodist Church |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Converted church/film and television studio |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| Location | Dickenson Road, Rusholme |

| Town or city | Manchester |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°27′09″N 2°13′11″W / 53.4524°N 2.2197°W |

| Construction started | 1862 |

| Opened |

|

| Closed | 1975 |

| Demolished | 1975 |

| Owner |

|

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | William Haley & Son |

| Known for | Broadcast of the first episodes of Top of the Pops |

Dickenson Road Studios was a film and television studio in Rusholme, Manchester, in North-West England. It was originally set up in 1947 in a former Wesleyan Methodist Chapel by the film production company Mancunian Films and was acquired by BBC Television in 1954. The studio was used for early editions of the music chart show Top of the Pops from 1964.

The studio closed in 1975, when the BBC moved to New Broadcasting House on Oxford Road and the building was demolished.

History

Dickenson Rd Wesleyan Methodist Church was built in 1862 at a cost of £4,000, designed in a Geometric Decorated Gothic Revival style by the Manchester architects William Haley & Son. The gable-fronted building had a high-pitched roof surmounted with a decorated stone cross. It was divided into a nave and transepts. At the eastern end was an apse with three stained-glass windows, and there were future plans to extend the building further. The exterior was faced in Pierrepoint and Hollington stone.[1][2]

The Wesleyan Methodists were a branch of the Nonconformist Christian denominations that developed from the religious teachings of John Wesley. In 1932, the Wesleyans merged with the Primitive Methodist and the United Methodist Churches to form the Methodist Church of Great Britain. As a result of this merger, many churches and chapels closed, and Dickenson Rd Church closed to worship in 1937.[3]

Mancunian Films

In the 1930s, British film producer John E. Blakeley was expanding his film production business, Blakeley's Productions Ltd. Despite the low production values of filming in unsatisfactory rented spaces, the company's film releases had helped to launch the career of the variety entertainer George Formby. Blakeley's films relaunched his company as Mancunian Films.[4][5]

Focussing on the northern market, Blakeley decided to establish his own studio in Manchester. In 1947, he purchased the disused church on Dickenson Road and converted the building into a two-stage film studio at a cost of £70,000, creating the first British film studio outside the South East of England.[6] The studio received funding from the National Film Finance Corporation (NFFC), which provided grants to support independent British studios.[7]

Dickenson Road Studios were officially opened in 1947 at a ceremony attended by "John E." and Mancunian screen stars George Formby, Frank Randle, Norman Evans, Dan Young and Sandy Powell.[4] The new production operation earned the nickname "the Hollywood of the North",[4] or alternatively "Jollywood", on account of its output of comedy films. Critics of Mancunian's productions dubbed the studio the "Corn Exchange", a humorous reference to the Corn Exchange in Manchester ("corn" being a slang term for unoriginal, poor-quality humour).[7]

The first production there was Cup-tie Honeymoon in 1948, starring Sandy Powell and featuring future Coronation Street stars Pat Phoenix and Bernard Youens.[8] It was filmed at the Dickenson Road Studios, with location filming taking place at Maine Road football stadium.[9] Over the next six years, the films featured northern favourites Frank Randle, Josef Locke, Diana Dors, and Jimmy Clitheroe. The studio, often worked on shoestring budgets, was profitable, but Blakely decided to retire when he reached 65. Mancunian Films continued under Blakeley's son Tom for many years, providing facilities for Hammer Horror productions (Hell Is a City, 1960) and making a number of B-movies.[10][11]

Mancunian Films productions after 1948 included:[8]

- Cup-tie Honeymoon (1948)

- International Circus Review (1948)

- Holidays with Pay (1948)

- Showground of the North (1948)

- Somewhere in Politics (1948)

- What a Carry On (1949)

- School for Randle (1949)

- Over the Garden Wall (1950)

- Let's Have a Murder (1950)

- Love's a Luxury (1952)

- Those People Next Door (1952)

- It's a Grand Life (1953)

BBC Television

In the 1950s, the growing reach of television affected the size of cinema audiences, and as the mass media market evolved, numerous film studios were taken over by emerging television broadcasters. In London, the BBC acquired Lime Grove Studios from Gainsborough Pictures in 1949 and Ealing Studios in 1955. Dickenson Road Studios was bought from Mancunian by the BBC in 1954, and it became the first regional BBC Television studio outside London.[4][12] Programmes made by the BBC at the studios included series starring comedian Harry Worth and variety programmes, and the studio became the production headquarters for BBC television drama in the North, being used for the production of early plays by television writers such as Alan Plater.[13][14] The studio possessed no recording facilities, the pictures were fed by landline down to London for recording and were then played back for checking at the studio.

The first episode of the pop music television show Top of the Pops was broadcast from Dickenson Road Studio on 1 January 1964, presented by Jimmy Savile and Alan Freeman and produced by Johnnie Stewart. The programme opened with The Rolling Stones performing "I Wanna Be Your Man", and featured Dusty Springfield singing "I Only Want to Be with You" and The Hollies performing "Stay". It concluded with a recording of "I Want to Hold Your Hand" by The Beatles, played over a montage of film clips.[15][16][17][18][19] The programme was broadcast from Studio A at Dickenson Road for three years, hosted by presenters such as Savile, Freeman, Pete Murray and David Jacobs. It also featured Samantha Juste as the "disc girl", the female DJ who played the week's hit records on a record turntable live on-air.[20] Early Top of the Pops episodes were broadcast live and initially, performers mimed to their own records. This practice was not always successful; when The Swinging Blue Jeans were broadcast miming to their version of "Hippy Hippy Shake" in 1964, the record was played at the wrong speed, disrupting the performance.[21] [notes 1][22]

During the time the programme was broadcast from Dickenson Road Studios, many popular acts performed there; The Kinks made their Top of the Pops debut at Dickenson Road on 19 August 1964 with "You Really Got Me";[23] The Who debuted on 11 March 1965 with "I Can't Explain"; The Merseybeats, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Peter and Gordon, The Fourmost, The Small Faces, Ken Dodd, Val Doonican, Them, Cliff Richard and The Animals were also among the early acts to appear there.[24] Due to the limitations of the building, The Beatles did not appear in person on the show; their performances were pre-recorded at the Riverside Studios in London.[25][notes 2][26][27] No archive recordings remain in existence of the first broadcasts from Dickenson Road, it is not known if the earliest episodes were ever recorded.[28] However, the Fallowfield-born photographer Harry Goodwin took many photographs of stars who performed at Dickenson Road Studios in the 1960s, including shots of James Brown and Stevie Wonder.[29][30] Goodwin's weekly fee of £30 was considered very low; Mick Jagger advised him to demand more, but as a compromise, Johnnie Stewart gave Goodwin a weekly mention on the programme's closing credits.[31]

Performers and production staff have remarked on the experience of hosting the leading pop celebrities of the day at such an unglamorous location as a former church in the North. The then production secretary of Top of the Pops, Frances Line, recalled the unusual sight of television cameras moving up and down the interior of an old church. Performers on the show often had to make a long journey from London by British Rail, but as the programme gained viewers, BBC budgets extended to flying the stars from Heathrow Airport. At the end of the live broadcast, performers would then take taxis to catch the evening flight back to London. Ground staff at Manchester Airport grew accustomed to dealing with pop stars checking in late.[32]

Bobby Elliott, drummer with The Hollies, remembered that he travelled north with his group in a van. His impression of Dickenson Road Studios was: "Quite cosy. Great little canteen with friendly ladies who served tea in proper cups on saucers." The crowded canteen was usually packed with stars, which sometimes resulted in conflict. After a dinner lady asked for autographs from members of The Swinging Blue Jeans, the band became embroiled in a fist-fight over a biro with Keith Richards and Mick Jagger of The Rolling Stones.[33]

.jpg.webp)

The studios remained the home of Top of the Pops until 1966, when the show moved to a larger facility at Lime Grove Studios in London. These studios gave Johnnie Stewart more flexibility in the way the show was presented, with larger sets and the ability to attract a more trendy "Swinging London" studio audience. The first broadcast of Top of the Pops from Lime Grove went out on 20 January 1966.[34][35][36]

Eventually the BBC's operations at Dickenson Road were transferred to the BBC's new building at New Broadcasting House on Oxford Road. The Dickenson Road building was demolished in 1975.[37] Today the site is occupied by houses, and a plaque affixed to the side of a house commemorates the history of Dickenson Road Studios.[3]

Notes

- ↑ After later intervention by the Musicians' Union, songs were either performed live accompanied by an orchestra or to a specially recorded backing track.

- ↑ The Beatles' only live appearance on Top of the Pops was at BBC Television Centre on 16 June 1966, when they performed "Paperback Writer" and "Rain".

References

- ↑ Godwin, George, ed. (12 April 1862). "Works in Manchester". The Builder. London. XX: 264. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ "Wesleyan Chapel: Dickinson Road Rusholme - Building | Architects of Greater Manchester". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- 1 2 "Dickenson Rd Wesleyan Methodist, Rusholme, Lancashire". Genuki. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Richards 1997, p. 276.

- ↑ "Film Studios and Industry Bodies: Mancunian Studios". BFI Screenonline. BFI. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ "Mancunian Films". BBC Inside Out. 17 February 2003. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- 1 2 Hunter & Porter 2012, p. 60.

- 1 2 "Early Mancunian Movies". iNostalgia. 16 February 2022. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Glynn, Stephen (3 May 2018). The British Football Film. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-319-77727-6. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ Warren, Patricia (2001). British Film Studios: An Illustrated History. London: B.T. Batsford. p. 116.

- ↑ "The Mancunian Film Corporation". iNostalgia. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ Lee, CP (20 January 2012). "Mancunian Film Company History". It's a Hot 'Un. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ Bignell, J.; Lacey, S. (12 May 2014). British Television Drama: Past, Present and Future. Springer. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-137-32758-1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Plater, Alan (15 December 2003). Trussler, Simon; Barker, Clive (eds.). "Learning the Facts of Life: Forty Years as a TV Dramatist". New Theatre Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. 19 (75): 203–213. doi:10.1017/S0266464X03000113. S2CID 193225015. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Simpson 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Davies, Dan (17 July 2014). In Plain Sight: The Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile. Quercus. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-78206-745-0. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ Millward, Stephen (1 December 2012). Changing Times: Music and Politics In 1964. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-78088-344-1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Reade, Lindsay (15 August 2016). "3. The Hippies' Revenge?". Mr Manchester and the Factory Girl: The Story of Tony and Lindsay Wilson. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85965-875-1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ "Been and Gone: Doctor Who's longest-serving director and Top of the Pops disc spinner". BBC News. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ "How we made Top of the Pops". the Guardian. 4 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 34.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, pp. 33–38.

- ↑ "www.thebeatlesinmanchester.co.uk - TOP OF THE POPS". thebeatlesinmanchester.co.uk. The Beatles in Manchester. 4 September 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ "Unique Beatles recording lost". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2003. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 35.

- ↑ "Loss of the Pops". Manchester Evening News. 10 August 2004. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Johnstone, Ellie-Jo. "Celebrating a century: 100 years of the BBC in Manchester". Confidentials. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ "Harry Goodwin, a former Top Of The Pops photographer, dies". BBC News. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 38.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Humphries 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ "Top of the Pops - BBC Studios (Rusholme)". www.manchesterbeat.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ McShane, John (6 May 2013). Savile - The Beast: The Inside Story of the Greatest Scandal in TV History. Kings Road Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78219-626-6. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Taylor, Paul (17 June 2011). "The end of a golden telly era as the BBC moves from Oxford Road to MediaCityUK". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

Sources

- Hunter, I. Q.; Porter, Laraine (4 May 2012). British Comedy Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-50837-0. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- Richards, Jeffrey (1997). Films and British National Identity: From Dickens to Dad's Army. Manchester & New York City: Manchester University Press. p. 267. ISBN 9780719047435.

- Simpson, Jeff (2002). Top of the Pops: 1964-2002. BBC Worldwide. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-563-53476-1. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- Humphries, Patrick (28 November 2013). Top of the Pops 50th Anniversary. McNidder and Grace Limited. ISBN 978-0-85716-063-8. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

See also

External links

- "A tour of Wilmslow Road". Rusholme & Victoria Park Archive. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- First broadcast of Top of the Pops on Wednesday 1 January 1964, as listed in Radio Times

- Productions at Film Studios Manchester on IMDb

- "Top of the Pops 60s Episode Guide". Top of the Pops Archive. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.