Diego Rivera | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez December 8, 1886 Guanajuato City, Mexico |

| Died | November 24, 1957 (aged 70) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Panteón de Dolores, Mexico |

| Education | San Carlos Academy |

| Known for | Painting, murals |

| Notable work | Man, Controller of the Universe, The History of Mexico, Detroit Industry Murals |

| Movement | |

| Spouses |

(m. 1940; died 1954)Emma Hurtado (m. 1955) |

| Relatives |

|

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez,[1] known as Diego Rivera (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈdjeɣo riˈβeɾa]; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957), was a prominent Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the mural movement in Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals in, among other places, Mexico City, Chapingo, and Cuernavaca, Mexico; and San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City, United States. In 1931, a retrospective exhibition of his works was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; this was before he completed his 27-mural series known as Detroit Industry Murals.

Rivera had four wives and numerous children, including at least one natural (illegitimate) daughter. His first child and only son died at the age of two. His third wife was fellow Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, with whom he had a volatile relationship that continued until her death. His fourth and final wife was his agent.

Due to his importance in the country's art history, the government of Mexico declared Rivera's works as monumentos históricos.[2] As of 2018, Rivera holds the record for highest price at auction for a work by a Latin American artist. The 1931 painting The Rivals, part of the record-setting Collection of Peggy Rockefeller and David Rockefeller, sold for US$9.76 million.[3]

Personal life

Rivera was born on December 8, 1886, as one of twin boys in Guanajuato, Mexico, to María del Pilar Barrientos and Diego Rivera Acosta, a well-to-do couple.[1] His twin brother Carlos died two years after they were born.[4]

His mother María del Pilar Barrientos was said to have converso ancestry (Spanish ancestors who were forced to convert from Judaism to Catholicism in the 15th and 16th centuries).[5] Rivera wrote in 1935: "My Jewishness is the dominant element in my life", despite never being raised practicing any Jewish faith, Rivera felt his Jewish ancestry informed his art and gave him "sympathy with the downtrodden masses".[6][1] Diego was of Spanish, Amerindian, African, Italian, Jewish, Russian, and Portuguese descent.[1][7][8]

Rivera began drawing at the age of three, a year after his twin brother died. When he was caught drawing on the walls of the house, his parents installed chalkboards and canvas on the walls to encourage him.

Marriages and families

After moving to Paris, Rivera met Angelina Beloff, an artist from the pre-Revolutionary Russian Empire. They married in 1911, and had a son, Diego (1916–1918), who died young. During this time, Rivera also had a relationship with painter Maria Vorobieff-Stebelska, who gave birth to a daughter named Marika Rivera in 1918 or 1919.[9]

Rivera divorced Beloff and married Guadalupe Marín as his second wife in June 1922, after having returned to Mexico. They had two daughters together: Ruth and Guadalupe.

He was still married when he met art student Frida Kahlo in Mexico. They began a passionate affair and, after he divorced Marín, Rivera married Kahlo on August 21, 1929. He was 42 and she was 22. Their mutual infidelities and his violent temper resulted in divorce in 1939, but they remarried December 8, 1940, in San Francisco, California.

A year after Kahlo's death, on July 29, 1955, Rivera married Emma Hurtado, his agent since 1946.

In his later years Rivera lived in the United States and Mexico. Rivera died on November 24, 1957, at the age of 70. He was buried at the Panteón de Dolores in Mexico City.[10]

Personal beliefs

Rivera was an atheist. His mural Dreams of a Sunday in the Alameda depicted Ignacio Ramírez holding a sign that read, "God does not exist". This work caused a furor, but Rivera refused to remove the inscription. The painting was not shown for nine years – until Rivera agreed to remove the inscription. He stated: "To affirm 'God does not exist', I do not have to hide behind Don Ignacio Ramírez; I am an atheist and I consider religions to be a form of collective neurosis."[11]

Art education and circle

From the age of ten, Rivera studied art at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. He was sponsored to continue study in Europe by Teodoro A. Dehesa Méndez, the governor of the State of Veracruz. After arriving in Europe in 1907, Rivera first went to Madrid, Spain to study with Eduardo Chicharro.

From there he went to Paris, France, a destination for young European and American artists and writers, who settled in inexpensive flats in Montparnasse. His circle frequented La Ruche, where his Italian friend Amedeo Modigliani painted his portrait in 1914.[12] His circle of close friends included Ilya Ehrenburg, Chaïm Soutine, Modigliani and his wife Jeanne Hébuterne, Max Jacob, gallery owner Léopold Zborowski, and Moise Kisling. Rivera's former lover Marie Vorobieff-Stebelska (Marevna) honored the circle in her painting Homage to Friends from Montparnasse (1962).[13]

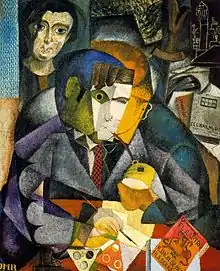

In those years, some prominent young painters were experimenting with an art form that would later be known as Cubism, a movement led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. From 1913 to 1917, Rivera enthusiastically embraced this new style.[14] Around 1917, inspired by Paul Cézanne's paintings, Rivera shifted toward Post-Impressionism, using simple forms and large patches of vivid colors. His paintings began to attract attention, and he was able to display them at several exhibitions.

Rivera claimed in his autobiography that, while in Mexico in 1904, he engaged in cannibalism, pooling his money with others to "purchase cadavers from the city morgue" and particularly "relish[ing] women's brains in vinaigrette".[15][16][17] This claim has been considered factually suspect[18] or an elaborate lie.[19] He wrote in his autobiography: "I believe that when man evolves a civilization higher than the mechanized but still primitive one he has now, the eating of human flesh will be sanctioned. For then man will have thrown off all of his superstitions and irrational taboos."[20]

Career in Mexico

In 1920, urged by Alberto J. Pani, the Mexican ambassador to France, Rivera left France and traveled through Italy studying its art, including Renaissance frescoes. After José Vasconcelos became Minister of Education, Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 to become involved in the government sponsored Mexican mural program planned by Vasconcelos.[21] The program included such Mexican artists as José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo, and the French artist Jean Charlot. In January 1922,[22] he painted – experimentally in encaustic – his first significant mural Creation[23] in the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City while guarding himself with a pistol against right-wing students.

In the autumn of 1922, Rivera participated in the founding of the Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors, and later that year he joined the Mexican Communist Party[24] (including its Central Committee). His murals, subsequently painted in fresco only, dealt with Mexican society and reflected the country's 1910 Revolution. Rivera developed his own native style based on large, simplified figures and bold colors with an Aztec influence clearly present in murals at the Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City[25] begun in September 1922, intended to consist of one hundred and twenty-four frescoes, and finished in 1928.[22] Rivera's art work, in a fashion similar to the steles of the Maya, tells stories. The mural En el Arsenal (In the Arsenal)[26] shows on the right-hand side Tina Modotti holding an ammunition belt and facing Julio Antonio Mella, in a light hat, and Vittorio Vidali behind in a black hat. However, the En el Arsenal detail shown does not include the right-hand side described nor any of the three individuals mentioned; instead it shows the left-hand side with Frida Kahlo handing out munitions. Leon Trotsky lived with Rivera and Kahlo for several months while exiled in Mexico.[27] Some of Rivera's most famous murals are featured at the National School of Agriculture (Chapingo Autonomous University of Agriculture) at Chapingo near Texcoco (1925–1927), in the Cortés Palace in Cuernavaca (1929–30), and the National Palace in Mexico City (1929–30, 1935).[28][29][30]

Rivera painted murals in the main hall and corridor at the Chapingo Autonomous University of Agriculture (UACh). He also painted a fresco mural titled Tierra Fecundada[31] (Fertile Land in English) in the university's chapel between 1923 and 1927. Fertile Land depicts the revolutionary struggles of Mexico's peasant (farmers) and working classes (industry) in part through the depiction of hammer and sickle joined by a star in the soffit of the chapel. In the mural, a "propagandist" points to another hammer and sickle. The mural features a woman with an ear of corn in each hand, which art critic Antonio Rodriguez describes as evocative of the Aztec goddess of maize in his book Canto a la Tierra: Los murales de Diego Rivera en la Capilla de Chapingo.

The corpses of revolutionary heroes Emiliano Zapata and Otilio Montano are shown in graves, their bodies fertilizing the maize field above. A sunflower in the center of the scene "glorifies those who died for an ideal and are reborn, transfigured, into the fertile cornfield of the nation", writes Rodrigues. The mural also depicts Rivera's wife Guadalupe Marin as a fertile nude goddess and their daughter Guadalupe Rivera y Marin as a cherub.[32]

The mural was slightly damaged in an earthquake, but has since been repaired and touched up, remaining in pristine form.

Later years

In the autumn of 1927, Rivera went to Moscow, Soviet Union, having accepted a government invitation to take part in the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. The following year, while still in the Soviet Union, he met American Alfred H. Barr Jr., who would soon become Rivera's friend and patron. Barr was the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[33]

Although commissioned to paint a mural for the Red Army Club in Moscow, in 1928 Rivera was ordered by authorities to leave the country because, he suspected, of "resentment on the part of certain Soviet artists."[34] He returned to Mexico.

In 1929, following the assassination of former president Álvaro Obregón the previous year, the government suppressed the Mexican Communist Party. That year Rivera was expelled from the party because of his suspected Trotskyite sympathies. In addition, observers noted that his 1928 mural In the Arsenal includes the figures of communists Tina Modotti, Cuban Julio Antonio Mella, and Italian Vittorio Vidali. After Mella was murdered in January 1929, allegedly by Stalinist assassin Vidali, Rivera was accused of having had advance knowledge of a planned attack.

After divorcing his third wife, Guadalupe (Lupe) Marin, Rivera married the much younger Frida Kahlo in August 1929. They had met when she was a student, and she was 22 years old when they married; Rivera was 42.

Also in 1929, American journalist Ernestine Evans's book The Frescoes of Diego Rivera, was published in New York City; it was the first English-language book on the artist. In December, Rivera accepted a commission from the American Ambassador to Mexico to paint murals in the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca, where the US had a consulate.[35]

In September 1930, Rivera accepted a commission by architect Timothy L. Pflueger for two works related to his design projects in San Francisco. Rivera and Kahlo went to the city in November. Rivera painted a mural for the City Club of the San Francisco Stock Exchange for US$2,500.[36] He also completed a fresco for the California School of Fine Art, a work that was later relocated to what is now the Diego Rivera Gallery at the San Francisco Art Institute.[35]

During this period, Rivera and Kahlo worked and lived at the studio of Ralph Stackpole, who had recommended Rivera to Pflueger. Rivera met Helen Wills Moody, a notable American tennis player, who modeled for his City Club mural.[36]

In November 1931, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City mounted a retrospective exhibition of Rivera's work; Kahlo attended with him.[37]

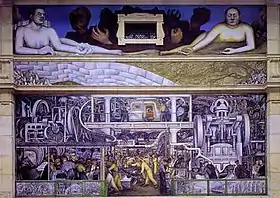

Between 1932 and 1933, Rivera completed a major commission: twenty-seven fresco panels, entitled Detroit Industry, on the walls of an inner court at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Part of the cost was paid by Edsel Ford, scion of the entrepreneur.

During the McCarthyism of the 1950s, a large sign was placed in the courtyard defending the artistic merit of the murals while attacking his politics as "detestable."[33]

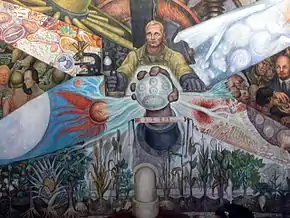

His mural Man at the Crossroads, originally a three-paneled work,[39] begun as a commission for John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1933 for the Rockefeller Center in New York City, was later destroyed. Because it included a portrait of Vladimir Lenin, former leader of the Soviet Union and Marxist pro-worker content, Rockefeller's son, the press, and some of the public protested, but the decision to destroy it was made by the management company. Anti-Communism ran high in some American circles, although many others in this period of the Great Depression had been drawn to the movement as offering hope to labor.

When Diego refused to remove Lenin from the painting, he was ordered to leave the US. One of Diego's assistants managed to take a few photographs of the work so Diego was able to later recreate it. American poet Archibald MacLeish wrote six "irony-laden" poems about the mural.[40] The New Yorker magazine published E. B. White's light poem, "I paint what I see: A ballad of artistic integrity", also in response to the controversy with number of sponsors taking offense to it.[41]

As a result of the negative publicity, officials in Chicago cancelled their commission for Rivera to paint a mural for the Chicago World's Fair. Rivera issued a press statement, saying that he would use the remaining money from his commission at Rockefeller Center to repaint the same mural, over and over, wherever he was asked, until the money ran out. He had been paid in full although the mural was reportedly destroyed. There have been rumors that the mural was covered over rather than removed and destroyed, but this has not been confirmed.

In December 1933, Rivera returned to Mexico. He repainted Man at the Crossroads in 1934 in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, calling this version Man, Controller of the Universe.

On June 5, 1940, invited again by Pflueger, Rivera returned for the last time to the United States to paint a ten-panel mural for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. His work, Pan American Unity was completed November 29, 1940. Rivera painted in front of attendees at the Exposition, which had already opened. He received US$1,000 per month and US$1,000 for travel expenses.[36] The mural includes representations of two of Pflueger's architectural works, and portraits of Rivera's wife, Frida Kahlo, woodcarver Dudley C. Carter, and actress Paulette Goddard. She is shown holding Rivera's hand as they plant a white tree together.[36] Rivera's assistants on the mural included Thelma Johnson Streat, a pioneer African-American artist, dancer, and textile designer. The mural and its archives are now held by City College of San Francisco.[42][43]

In 1946-47, Rivera painted A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, a fresco that featured a fully elaborated figure of La Calavera Catrina. This character, which was created by José Guadalupe Posada, originally consisted of a print depicting the head and shoulders of a skeletal woman in a big hat. Rivera endowed his Catrina figure with indigenous features and thus transformed her into a nationalist icon. Catrina is the most common image associated with Day of the Dead.[44]

Membership in AMORC

In 1926, Rivera became a member of AMORC, the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, an occult organization founded by American occultist Harvey Spencer Lewis. In 1926, Rivera was among the founders of AMORC's Mexico City lodge, called Quetzalcoatl after an ancient indigenous god. He painted an image of Quetzalcoatl for the local temple.[45]

In 1954, Rivera tried to be readmitted into the Mexican Communist Party. He had been expelled in part because of his support of Trotsky, who had been exiled and assassinated years before in Mexico. Rivera was required to justify his AMORC activities. At the time, the Mexican Communist Party excluded persons involved in Freemasonry, and regarded AMORC as suspiciously similar to Freemasonry.[46] Rivera told his questioners that, by joining AMORC, he wanted to infiltrate a typical "Yankee" organization on behalf of Communism. However, he also claimed that AMORC was "essentially materialist, insofar as it only admits different states of energy and matter, and is based on ancient Egyptian occult knowledge from Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti."[47]

Representation in other media

Diego Rivera has been portrayed in several films. He was played by Rubén Blades in Cradle Will Rock (1999), by Alfred Molina in Frida (2002), and (in a brief appearance) by José Montini in Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015).

Barbara Kingsolver's novel, The Lacuna features Rivera, Kahlo, and Leon Trotsky as major characters.

Gallery

Paintings

Self-portrait with Broad-Brimmed Hat, 1907, 84.5 × 61.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Self-portrait with Broad-Brimmed Hat, 1907, 84.5 × 61.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Avila Morning (The Ambles Valley), 1908, 97 × 123 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Avila Morning (The Ambles Valley), 1908, 97 × 123 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Street in Ávila (Ávila Landscape), 1908, 129 × 141 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Street in Ávila (Ávila Landscape), 1908, 129 × 141 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte El Picador, 1909, 177 × 113 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

El Picador, 1909, 177 × 113 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The House on the Bridge, 1909, 147 × 121 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

The House on the Bridge, 1909, 147 × 121 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) After the Storm (The Grounded Ship), 1910, 120.7 × 146.7 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

After the Storm (The Grounded Ship), 1910, 120.7 × 146.7 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte Landscape, 1911. Frida Kahlo Museum.

Landscape, 1911. Frida Kahlo Museum. Portrait of Adolfo Best Maugard, 1913, 227.5 × 161.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Portrait of Adolfo Best Maugard, 1913, 227.5 × 161.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte Adoration of the Virgin and Child, 1912–13, oil and encaustic on canvas, 150 × 120 cm, private collection

Adoration of the Virgin and Child, 1912–13, oil and encaustic on canvas, 150 × 120 cm, private collection The Sun Breaking through the Mist, 1913, 83.5 × 59 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

The Sun Breaking through the Mist, 1913, 83.5 × 59 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The Woman at the Well, 1913, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

The Woman at the Well, 1913, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte The Alarm Clock, 1914. Frida Kahlo Museum

The Alarm Clock, 1914. Frida Kahlo Museum%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_197.5_x_161.3_cm%252C_The_Arkansas_Arts_Center%252C_Little_Rock%252C_Arkansas.jpg.webp) Two Women (Dos Mujeres, Portrait of Angelina Beloff and Maria Dolores Bastian), 1914, 197.5 × 161.3 cm. Arkansas Arts Center

Two Women (Dos Mujeres, Portrait of Angelina Beloff and Maria Dolores Bastian), 1914, 197.5 × 161.3 cm. Arkansas Arts Center Portrait de Messieurs Kawashima et Foujita, 1914, oil and collage on canvas, 78.5 × 74 cm. Private collection

Portrait de Messieurs Kawashima et Foujita, 1914, oil and collage on canvas, 78.5 × 74 cm. Private collection Young Man with a Fountain Pen, 1914, 79.5 × 63.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Young Man with a Fountain Pen, 1914, 79.5 × 63.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo El Rastro, 1915, 27.5 × 38.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

El Rastro, 1915, 27.5 × 38.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, 1915, 109.6 × 90.2 cm. Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires

Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, 1915, 109.6 × 90.2 cm. Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires Zapata-style Landscape, 1915, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Zapata-style Landscape, 1915, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte Portrait of Marevna, c.1915, 145.7 × 112.7 cm. Art Institute of Chicago

Portrait of Marevna, c.1915, 145.7 × 112.7 cm. Art Institute of Chicago_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Seated Woman (Women with the Body of a Guitar), 1915–16. Frida Kahlo Museum

Seated Woman (Women with the Body of a Guitar), 1915–16. Frida Kahlo Museum Urban Landscape, 1916. Frida Kahlo Museum

Urban Landscape, 1916. Frida Kahlo Museum%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_67.8_x_53.7cm.jpg.webp) Still Life with Tulips (Naturaleza Muerta con Tulipanes), 1916, oil on canvas, 67.8 × 53.7 cm

Still Life with Tulips (Naturaleza Muerta con Tulipanes), 1916, oil on canvas, 67.8 × 53.7 cm Knife and Fruit in Front of the Window, 1917, 91.8 × 92.4 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Knife and Fruit in Front of the Window, 1917, 91.8 × 92.4 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo Still Life with Utensils, 1917, 71 × 54 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Still Life with Utensils, 1917, 71 × 54 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The Mathematician, 1919, 115.5 × 80.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

The Mathematician, 1919, 115.5 × 80.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo Maternidad, Angelina y el niño Diego (Motherhood, Angelina and the Child Diego), c. August 1916, oil on canvas, 134.5 × 88.5 cm, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil. This work forms part of Rivera's Crystal Cubist period

Maternidad, Angelina y el niño Diego (Motherhood, Angelina and the Child Diego), c. August 1916, oil on canvas, 134.5 × 88.5 cm, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil. This work forms part of Rivera's Crystal Cubist period

Murals

Mural of exploitation of Mexico by Spanish conquistadores, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (1929–1945)

Mural of exploitation of Mexico by Spanish conquistadores, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (1929–1945) Mural of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City Mural of the Aztec market of Tlatelolco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural of the Aztec market of Tlatelolco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City Mural showing Aztec production of gold, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural showing Aztec production of gold, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City Mural showing Totonaca celebrations and ceremonies, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural showing Totonaca celebrations and ceremonies, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx

Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Vladimir Lenin

Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Vladimir Lenin Mural (detail) Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central in Mexico City, featuring Rivera and Frida Kahlo standing by La Calavera Catrina (width: 15.6 m)

Mural (detail) Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central in Mexico City, featuring Rivera and Frida Kahlo standing by La Calavera Catrina (width: 15.6 m) Mural at the National Palace, Mexico City

Mural at the National Palace, Mexico City Diego Rivera's mural The History of Mexico at the National Palace in Mexico City

Diego Rivera's mural The History of Mexico at the National Palace in Mexico City

Recreation of Man at the Crossroads (renamed Man, Controller of the Universe), originally created in 1934 (detail)

Recreation of Man at the Crossroads (renamed Man, Controller of the Universe), originally created in 1934 (detail) View of the Murals by Diego Rivera in the Palacio Nacional

View of the Murals by Diego Rivera in the Palacio Nacional Detroit Industry, North Wall, 1932–33. Detroit Institute of Arts

Detroit Industry, North Wall, 1932–33. Detroit Institute of Arts Detroit Industry, South Wall, 1932–33. Detroit Institute of Arts

Detroit Industry, South Wall, 1932–33. Detroit Institute of Arts

Sculptures

Tlaloc Fountain in Cárcamo de Dolores, Mexico City (1951)

Tlaloc Fountain in Cárcamo de Dolores, Mexico City (1951) 3D mural of Quetzalcóatl in the Exekatlkalli (Casa de los Vientos) in Acapulco, Guerrero (1957)

3D mural of Quetzalcóatl in the Exekatlkalli (Casa de los Vientos) in Acapulco, Guerrero (1957)

See also

- List of works by Diego Rivera

- Anahuacalli Museum

- Crystal Cubism

- Elaine Hamilton-O'Neal

- Jewish Culture

- Gabriel Bracho, Venezuelan muralist

- Cárcamo de Dolores

- Glorious Victory painting of the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état that the CIA backed to overthrow the democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz.

- María Izquierdo

References

- 1 2 3 4 Marnham, Patrick (1998). "Dreaming With His Eyes Open, A Life of Diego Rivera". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ↑ Traurig, Greenberg (November 26, 2014). "In love with Diego or Frida? A brief look at Mexican art regulations". Cultural Assets. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Feingold, Spencer (May 10, 2018). "Diego Rivera painting becomes highest-priced Latin American art". CNN. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ↑ online biography Retrieved October 13, 2010

- ↑ Lipman, Jennifer (November 24, 2010). "On this day: Diego Rivera dies, November 24 1957: a portrait of an artist". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 21, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

His mother was a Converso, a Jew whose ancestors had been forced to convert to Catholicism. Although he was not raised as a Jew and later declared himself an atheist

- ↑ "Mexico Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Virtual Library, A Project of Aice. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Archived from the original on January 23, 2003. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "A ascendência portuguesa de Diego Rivera | BUALA". www.buala.org. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ "O sangue português de Diego Rivera".

- ↑ Angelina Beloff, Memorias

- ↑ "Diego Rivera — Biography". artinthepicture.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ Stein, Philip (1994). Siqueiros: His Life and Works. New York City: International Publishers Co. p. 176. ISBN 0-7178-0706-1.

- ↑ "Modigliani, Amedeo - 1914 Portrait of Diego Rivera (Museo de Arte, Sao Paolo, Brazil) | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. June 2, 2009. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ↑ "M. Marevna, 'Homage to Friends from Montparnasse', 1962, A private collection, Moscow". The State Russian Museum. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ Gale, Robert L. (February 2000). Millet, Francis Davis (1846-1912), artist and writer. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1700588.

- ↑ Rivera, Diego, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (with Gladys March), New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1991, p. 20; originally published by The Citadel Press, New York, 1960.

- ↑ Sleeping With the Enemy

- ↑ An experiment in cannibalism

- ↑ Lewis F. Petrinovich, The Cannibal Within, Transaction Publishers, 2000, ISBN 0202369501

- ↑ Pete Hamill, Diego Rivera, Harry N. Abrams, 1999, ISBN 0810932342

- ↑ Rivera, Diego, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (with Gladys March), 1991, p. 21.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera: Biography". Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- 1 2 "Diego Rivera: Chronology". Yahoo! GeoCities. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera. Creation. / La creación. 1922–3". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Fred Buch. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera. From the cycle: Political Vision of the Mexican People (Court of Fiestas): Insurrection aka The Distribution of Arms. / El Arsenal – Frida Kahlo repartiendoarmas". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire, W. W. Norton & Company, 2006, p. 225.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Answers.com. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Images of Murals by Diego Rivera in the Palacio Nacional de Mexico". homepages.bluffton.edu. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Scala Archives -". www.scalarchives.com. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ↑ "ART: The Mexico of My Father". May 11, 2016.

- 1 2 Schjeldahl, Peter (November 28, 2011). "The Painting on the Wall". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. pp. 84–85. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Rivera, Diego, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (with Gladys March), 1991, p. 93.

- 1 2 "The Commission". San Francisco Art Institute. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Poletti, Therese; Paiva, Tom (2008). Art Deco San Francisco: The Architecture of Timothy Pflueger. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-756-9.

- ↑ Gerry Souter (2012). Kahlo. New York: Parkstone International. ISBN 9781780424385. p. 18.

- ↑ "When Diego and Frida Came to Columbia". blogs.cul.columbia.edu. September 15, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Michael (January 23, 2014). "'Man at the Crossroads' art review". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ↑ "Archibald MacLeish Criticism". Enotes.com. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ↑ White, E. B. (May 20, 1933). "I paint what I see". The New Yorker. Art-talks.org. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ↑ "City College's "Pan American Unity" is at SFMOMA!". The Diego Rivera Mural Project. City College of San Francisco. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Pan American Unity Mural". City College of San Francisco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Cordova, Ruben C. (2019). "José Guadalupe Posada and Diego Rivera Fashion Catrina: From Sellout To National Icon (and Back Again?)". Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ↑ Raquel Tibol, "Apareció la serpiente: Diego Rivera y los rosacruces," Proceso 701 (April 9, 1990), pp. 50–53.

- ↑ Tibol, "Apareció la serpiente," p.53

- ↑ Diego Rivera, Arte y política, México: Grijalbo, 1979, p. 354. ISBN 968-419-083-2.

Further reading

- Aguilar, Louis. "Detroit was muse to legendary artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo". The Detroit News. April 6, 2011.

- Azuela, Alicia. Diego Rivera en Detroit. Mexico City: UNAM 1985.

- Bloch, Lucienne. "On location with Diego Rivera." Art in America 74 (February 1986, pp. 102–23.

- Craven, David. Diego Rivera as Epic Modernist. New York: G.K. Hall 1997.

- Dickerman, Leah, and Anna Indych-López. Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art 2011.

- Downs, Linda. Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals. Detroit: The Detroit Institute of Arts 1999.

- Evans, Robert [Joseph Freeman]. "Painting and Politics: The Case of Diego Rivera." New Masses (February 1932) 22-25.

- González Mello, Renato. "Manuel Gamio, Diego Rivera and the Politics of Mexican Anthropology." RES 45 (Spring 2004) 161-85.

- Lee, Anthony. Painting on the Left: Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco's Public Murals. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1999.

- Linsley, Robert. "Utopia Will Not be Televised: Rivera at Rockefeller Center." Oxford Art Journal 17, no. 2 (1994) 48-62.

- Moyssén, Xavier, ed. Diego Rivera: Textos de arte. Mexico City: UNAM 1986.

- Paquette, Catha (2017). At the Crossroads: Diego Rivera and his Patrons at MoMA, Rockefeller Center, and the Palace of Fine Arts. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1477311004.

- Rivera, Diego. Arte y política, Raquel Tibol, ed. Mexico City Grijalbo 1979.

- Rivera, Diego and Gladys March. My Life, Life: An Autobiography. New York: Dover Publications 1960.

- Rodrigues, Antonio. "Canto a la tierra: Los murales de Diego Rivera en la Capilla de Chapingo." (trans. Allyson Cadwell) Texcoco: Universidad Autonoma Chapingo, 1986 (1st reprint, 2000).

- Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros, London: Laurence King, 1993.

- Siqueiros, David Alfaro. "Rivera's Counter-Revolutionary Road." New Masses May 29, 1934.

- Wolfe, Bertram. The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera. New York: Stein and Day 1963.

- Wolfe, Bertram and Diego Rivera. Portrait of Mexico. New York: Covici, Friede Publishers 1937.

External links

- Creation (1931). From the Collections of the Library of Congress

- Trials of the Hero-Twins (1931) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Human Sacrifice Before Tohil (1931) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Cubist paintings by Rivera

- Diego Rivera at Curlie

- Diego Rivera discography at Discogs