A 3He/4He dilution refrigerator is a cryogenic device that provides continuous cooling to temperatures as low as 2 mK, with no moving parts in the low-temperature region.[1][2] The cooling power is provided by the heat of mixing of the helium-3 and helium-4 isotopes.

The dilution refrigerator was first proposed by Heinz London in the early 1950s, and was experimentally realized in 1964 in the Kamerlingh Onnes Laboratorium at Leiden University.[3] The field of dilution refrigeration is reviewed by Zu et al.[4]

Theory of operation

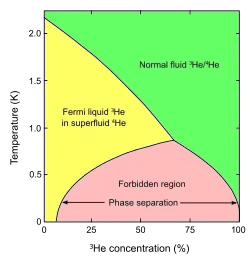

The refrigeration process uses a mixture of two isotopes of helium: helium-3 and helium-4. When cooled below approximately 870 millikelvins, the mixture undergoes spontaneous phase separation to form a 3He-rich phase (the concentrated phase) and a 3He-poor phase (the dilute phase). As shown in the phase diagram, at very low temperatures the concentrated phase is essentially pure 3He, while the dilute phase contains about 6.6% 3He and 93.4% 4He. The working fluid is 3He, which is circulated by vacuum pumps at room temperature.

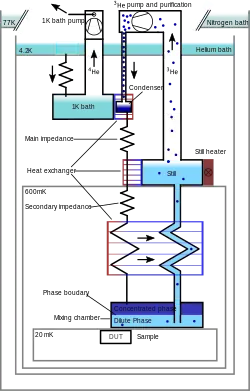

The 3He enters the cryostat at a pressure of a few hundred millibar. In the classic dilution refrigerator (known as a wet dilution refrigerator), the 3He is precooled and purified by liquid nitrogen at 77 K and a 4He bath at 4.2 K. Next, the 3He enters a vacuum chamber where it is further cooled to a temperature of 1.2–1.5 K by the 1 K bath, a vacuum-pumped 4He bath (as decreasing the pressure of the helium reservoir depresses its boiling point). The 1 K bath liquefies the 3He gas and removes the heat of condensation. The 3He then enters the main impedance, a capillary with a large flow resistance. It is cooled by the still (described below) to a temperature 500–700 mK. Subsequently, the 3He flows through a secondary impedance and one side of a set of counterflow heat exchangers where it is cooled by a cold flow of 3He. Finally, the pure 3He enters the mixing chamber, the coldest area of the device.

In the mixing chamber, two phases of the 3He–4He mixture, the concentrated phase (practically 100% 3He) and the dilute phase (about 6.6% 3He and 93.4% 4He), are in equilibrium and separated by a phase boundary. Inside the chamber, the 3He is diluted as it flows from the concentrated phase through the phase boundary into the dilute phase. The heat necessary for the dilution is the useful cooling power of the refrigerator, as the process of moving the 3He through the phase boundary is endothermic and removes heat from the mixing chamber environment. The 3He then leaves the mixing chamber in the dilute phase. On the dilute side and in the still the 3He flows through superfluid 4He which is at rest. The 3He is driven through the dilute channel by a pressure gradient just like any other viscous fluid.[5] On its way up, the cold, dilute 3He cools the downward flowing concentrated 3He via the heat exchangers and enters the still. The pressure in the still is kept low (about 10 Pa) by the pumps at room temperature. The vapor in the still is practically pure 3He, which has a much higher partial pressure than 4He at 500–700 mK. Heat is supplied to the still to maintain a steady flow of 3He. The pumps compress the 3He to a pressure of a few hundred millibar and feed it back into the cryostat, completing the cycle.

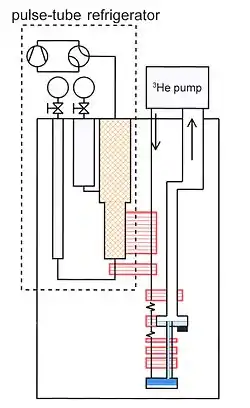

Cryogen-free dilution refrigerators

Modern dilution refrigerators can precool the 3He with a cryocooler in place of liquid nitrogen, liquid helium, and a 1 K bath.[6] No external supply of cryogenic liquids is needed in these "dry cryostats" and operation can be highly automated. However, dry cryostats have high energy requirements and are subject to mechanical vibrations, such as those produced by pulse tube refrigerators. The first experimental machines were built in the 1990s, when (commercial) cryocoolers became available, capable of reaching a temperature lower than that of liquid helium and having sufficient cooling power (on the order of 1 Watt at 4.2 K).[7] Pulse tube coolers are commonly used cryocoolers in dry dilution refrigerators.

Dry dilution refrigerators generally follow one of two designs. One design incorporates an inner vacuum can, which is used to initially precool the machine from room temperature down to the base temperature of the pulse tube cooler (using heat-exchange gas). However, every time the refrigerator is cooled down, a vacuum seal that holds at cryogenic temperatures needs to be made, and low temperature vacuum feed-throughs must be used for the experimental wiring. The other design is more demanding to realize, requiring heat switches that are necessary for precooling, but no inner vacuum can is needed, greatly reducing the complexity of the experimental wiring.

Cooling power

The cooling power (in watts) at the mixing chamber is approximately given by

where is the 3He molar circulation rate, Tm is the mixing-chamber temperature, and Ti the temperature of the 3He entering the mixing chamber. There will only be useful cooling when

This sets a maximum temperature of the last heat exchanger, as above this all cooling power is used up only cooling the incident 3He.

Inside of a mixing chamber there is negligible thermal resistance between the pure and dilute phases, and the cooling power reduces to

A low Tm can only be reached if Ti is low. In dilution refrigerators, Ti is reduced by using heat exchangers as shown in the schematic diagram of the low-temperature region above. However, at very low temperatures this becomes more and more difficult due to the so-called Kapitza resistance. This is a heat resistance at the surface between the helium liquids and the solid body of the heat exchanger. It is inversely proportional to T4 and the heat-exchanging surface area A. In other words: to get the same heat resistance one needs to increase the surface by a factor 10,000 if the temperature reduces by a factor 10. In order to get a low thermal resistance at low temperatures (below about 30 mK), a large surface area is needed. The lower the temperature, the larger the area. In practice, one uses very fine silver powder.

Limitations

There is no fundamental limiting low temperature of dilution refrigerators. Yet the temperature range is limited to about 2 mK for practical reasons. At very low temperatures both the viscosity and the thermal conductivity of the circulating fluid become larger if the temperature is lowered. To reduce the viscous heating the diameters of the inlet and outlet tubes of the mixing chamber must go as T−3

m and to get low heat flow the lengths of the tubes should go as T−8

m. That means that, to reduce the temperature by a factor 2, one needs to increase the diameter by a factor 8 and the length by a factor 256. Hence the volume should be increased by a factor 214 = 16,384. In other words: every cm3 at 2 mK would become 16,384 cm3 at 1 mK. The machines would become very big and very expensive. There is a powerful alternative for cooling below 2 mK: nuclear demagnetization.

See also

References

- ↑ Lounasmaa, O.V. (1974). Experimental Principles and Methods Below 1 K. London: Academic Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-12-455950-9.

- ↑ Pobell, Frank (2007). Matter and Methods at Low Temperatures. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 461. ISBN 978-3-540-46360-3.

- ↑ Das, P.; Ouboter, R. B.; Taconis, K. W. (1965). "A Realization of a London-Clarke-Mendoza Type Refrigerator". Low Temperature Physics LT9. p. 1253. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-6443-4_133. ISBN 978-1-4899-6217-1.

- ↑ Zu, H.; Dai, W.; de Waele, A.T.A.M. (2022). "Development of dilution refrigerators – A review". Cryogenics. 121. doi:10.1016/j.cryogenics.2021.103390. ISSN 0011-2275. S2CID 244005391.

- ↑ de Waele, A.Th.A.M.; Kuerten, J.G.M. (1991). "Thermodynamics and hydrodynamics of 3He–4He mixtures". In Brewer, D. F. (ed.). Progress in Low Temperature Physics, Volume 13. Elsevier. pp. 167–218. ISBN 978-0-08-087308-4.

- ↑ de Waele, A. T. A. M. (2011). "Basic Operation of Cryocoolers and Related Thermal Machines". Journal of Low Temperature Physics. 164 (5–6): 179–236. Bibcode:2011JLTP..164..179D. doi:10.1007/s10909-011-0373-x.

- ↑ Uhlig, K.; Hehn, W. (1997). "3He/4He Dilution refrigerator precooled by Gifford-McMahon refrigerator". Cryogenics. 37 (5): 279. Bibcode:1997Cryo...37..279U. doi:10.1016/S0011-2275(97)00026-X.

- H. E. Hall; P. J. Ford; K. Thomson (1966). "A helium-3 dilution refrigerator". Cryogenics. 6 (2): 80–88. Bibcode:1966Cryo....6...80H. doi:10.1016/0011-2275(66)90034-8.

- J. C. Wheatley; O. E. Vilches; W. R. Abel (1968). "Principles and methods of dilution refrigeration". Journal of Low Temperature Physics. 4: 1–64. doi:10.1007/BF00628435. S2CID 123091791.

- T. O. Niinikoski (1971). "A horizontal dilution refrigerator with very high cooling power". Nuclear Instruments and Methods. 97 (1): 95–101. Bibcode:1971NucIM..97...95N. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(71)90518-0.

- G. J. Frossati (1992). "Experimental techniques: methods for cooling below 300 mK". Journal of Low Temperature Physics. 87 (3–4): 595–633. Bibcode:1992JLTP...87..595F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.632.2758. doi:10.1007/bf00114918. S2CID 120814643.

External links

- Lancaster University, Ultra Low Temperature Physics - Description of dilution refrigeration.

- Harvard University, Marcus Lab - Hitchhiker's Guide to the Dilution Refrigerator.