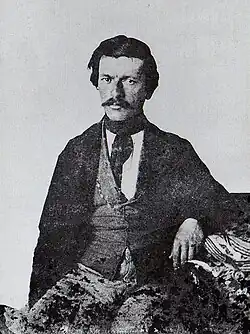

Dimitrije "Mita" Avramović (Serbian Cyrillic: Димитрије Мита Митриновић; 15 March 1815 – 1 March 1855) was a Serbian writer, iconographer, caricaturist and painter in the Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era and best known for his iconostasis and frescos. Avramović also translated from German into Serbian Johann Joachim Winckelmann's Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums ("The History of Art in Antiquity") and other writings. He is considered the father of modern comic strips in Serbia. His caricatures were used to fight against the authoritarian rule of the masses in both the Austrian Empire and the Ottoman Empire at the time.[1]

Biography

He was born in Šajkaš, where he, as a boy, moved with his family to Novi Sad where he started schooling. In 1833 he went to Vienna for the first time, then again in 1835. He studied painting in Vienna privately with Friedrich Amerling, and then in 1836 to 1839 he was enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. His professor of history was Leopold Kupelwieser.

In 1840, Avramović came to Belgrade, perhaps following the recommendation of Vuk Karadžić, and in the following year, in 1841, he began to work on painting icons and walls (frescoes) in the Cathedral Church in Belgrade (completed in 1845),[2] the iconostasis and walls of the Karadjordjevich church in the town of Topola,[3] the iconostasis of the Vrdnik-Ravanica Monastery, and the Orthodox Church in Futog. While painting the iconostasis in Topola, he visited the medieval monasteries in Serbia in 1846, including Manasija and Ravanica. Then he began to write about monuments in Serbia. The following year, thanks to Jovan Sterija Popović, he received funds to travel to the Holy Mountain, better known as Mount Athos in Greece, and do research.[4] That same year (1847), he was elected honorary member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, becoming the first Serbian artist to whom such an honour was bestowed.

In the 1848 Hungarian Revolution erupted, and Avramovic then actively participated in a propaganda battle drawing political cartoons. In this activity, he became a pioneer who launched the art of caricature in Serbia.

In 1851 Avramović married, and next year he moved to Novi Sad, where he made his permanent home. Between 1852 and 1853 Avramović painted the iconostasis and walls (frescoes) in the Vrdnik-Ravanica Monastery in Fruska Gora, then began painting the iconostasis in St. John the Sajkaca, and then, in 1855, began to paint the church of Saints Kuzman and Damjan in Old Futog. In parallel, he published cartoons, articles and historical contributions in several magazines. His composition Apotheosis of Lukijan Mušicki is considered to be the first classicist composition in Serbian painting.[5][6]

His life's desire was to paint the iconostasis of the church in his native Šajkaš, but his premature death did not allow him to complete his work. Along the churches and monasteries, his works are kept in the National Museum in Belgrade and at the Gallery of Matica Srpska in Novi Sad.

He died of a heart attack in Novi Sad in 1855. He was 40.

Works

He wrote two scholarly books on art from Mount Athos after visiting the monasteries there, Opisanie drevnosti Srbski u svetoi (Atonskoi) Gori (Description of Serbian Antiquities on the Holy Mountain of Athos; 1847)[7][8] and Sveta Gora sa strane vere, hudožestva i povestnice (The Holy Mountain from the standpoint of Religion, Art and History; 1848).

Avramović not only informed the Serbian public about the treasures of Athos, but also described in detail the whole area of the tiny monastic state. In fact, he accelerated the development of Serbian studies, while at the same time fostering a real Hilandar cult among a wide circle of readers. Questions relating to Hilandar and its antiquities began to occupy a place in all phases of organized scientific research, which was sponsored in the 1841-1864 period by the Society of Serbian Letters, and from 1864 to 1882 by the Serbian Learned Society or better still the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

See also

References

- ↑ "Vreme - Vek stripa u Srbiji: O "Nevenu" i drugim stvarima". www.vreme.com. 19 September 2007. Retrieved Apr 23, 2021.

- ↑ Mitchell, Laurence (2007). Bradt Travel Guide Serbia. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841622033.

- ↑ Jovanović, Miodrag (1989). Oplenac: Hram svetog Đorđa i mauzolej Karađorđevića. Művelődési, Oktatási és Tájékoztatási Központ. ISBN 9788672130096.

- ↑ Jovanović, Miodrag (1989). Oplenac: Hram svetog Đorđa i mauzolej Karađorđevića. Művelődési, Oktatási és Tájékoztatási Központ. ISBN 9788672130096.

- ↑ Stelè, Francè (1971). Art on the Soil of Yugoslavia from Prehistoric Times to the Present. Federal Commission for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries.

- ↑ Janićijević, Jovan (1998). The cultural treasury of Serbia. IDEA. ISBN 9788675470397.

- ↑ Avramović, Dimitrije (1847). Описанiе древностiй Србски у светой (Атонской) Гори. Печатано у Кнъигопечатнъи Княжества Србскогъ.

- ↑ Avramović, Dimitrije (1848). Sveta Gora sa strane vere, hudožestva i povestnice (in Russian). U Kniažesko-Srbskoĭ Knʹigopečatnʹi.

External links

- Short Biography at the Wayback Machine (archived November 4, 2008) (in Serbian)