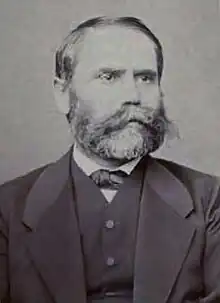

Dimitrije Matić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Education | |

| In office 22 October 1859 – April 1860 | |

| Monarch | Miloš Obrenović |

| Preceded by | Jevtimije Ugričić |

| Succeeded by | Ljubomir Nenadović |

| Secretary General of the State Council | |

| In office 1862–1866 | |

| Minister of Education | |

| In office 24 September 1868 – 10 August 1872 | |

| Monarch | Mihailo Obrenović |

| Preceded by | Panta Jovanović |

| Succeeded by | Stojan Veljković |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 24 September 1868 – 10 August 1872 | |

| Monarch | Mihailo Obrenović |

| Preceded by | Radivoje Milojković |

| Succeeded by | Jovan Ristić |

| President of the National Assembly Principality of Serbia | |

| In office 1 October 1878 – 5 December 1879 | |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 1 October 1878 – 5 December 1879 | |

| Monarch | Milan Obrenović |

| Preceded by | Jevrem Grujić |

| Succeeded by | Stojan Veljković |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 August 1821 Ruma, Kingdom of Slavonia |

| Died | October 17, 1884 (aged 63) Belgrade |

| Alma mater | Licej Kneževine Srbije University of Leipzig University of Heideberg |

| Occupation | politician, professor, diplomat, author |

Dimitrije Matić (Serbian: Димитрије Матић; 18 August 1821 – 17 October 1884) was a Serbian philosopher, jurist, professor, and politician who served as Minister of Education, Minister of Justice and Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was President of the National Assembly, which ratified the 1878 Treaty of Berlin proclaiming Serbia's independence.

He was a liberal-minded philosopher and politician who believed that the rule of force was unacceptable and that governments should promote and support popular education.[1] A prominent lawyer, writer and translator, he helped organized the college's law school; a prominent statesman, he secured major reforms in education. Matić was a tireless worker who dedicated his life to the creation of modern Serbia.[2]

Early life and education

Dimitrije Matić was born in 1821 in Ruma, the Kingdom of Slavonia, a province of the Habsburg monarchy within the Austrian Empire. His father, Iliya Matić, is said to have participated in the wars against Napoleon. His mother Spasenija was the aunt of Vladimir Jovanović. Dimitrije Matić had three brothers Matej, Miloje, and Djordje. Matić completed elementary school in Ruma, a secondary school in Sremski Karlovci before moving to the Principality of Serbia.[3]

He first attended Military School then after being offered a scholarship entered the newly founded Lyceum. The teachers had been trained abroad in Austria, Switzerland, and France and the classes were taught in Latin and German.

In the summer of 1840, Matić completed his cursus of Philosophy and then a year later his Legal Studies. The same year he moved to Belgrade joining his older brother Matej, who works as a clerk in the office of Prince Mihailo Obrenović, and entered the civil service.[4] After the Skupština elected Alexander Karađorđević there is a shift of dynasty and Mihailo Obrenović is deposed, Matić left the country with the Prince; during that time Matić lived in the Vrdnik Monastery on Fruška Gora mountain returning in 1843. On his return, he starts working as a lawyer and becomes secretary of Captain Miša Anastasijević.a

Matić received a post-graduate scholarship from the government to study philosophy in Berlin and Law in Heidelberg.[5] In 1847 he received his Ph.D. degree in philosophy at the University of Leipzig. His doctoral thesis was called: Dissertatio de via qua Fichtii, Schellingii, Hegeliique philosophia e speculativa investigatione Kantiana exculta sit; it addressed the question of how the philosophy of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel developed from Immanuel Kant's speculative thought. Among his professors in Berlin were Hegel's successor Georg Andreas Gabler (1786–1853), Otto Friedrich Gruppe and Johann Karl Wilhelm Vatke. He was mostly influenced by his Berlin professor Karl Ludwig Michelet, with whom he established a lifelong correspondence. While getting his law degree in Heidelberg he also studied Political Economy under Karl Heinrich Rau.[6] After obtaining the approval of the Ministry of Education, he left Heidelberg for Paris to extend his law studies.[7]

During the uprising of the Serbs against the force of Hungary, Matić was a member of the People's Committee in Karlovci and participated in organizing the army as deputy secretary of the Military Council, as an elected member of the Main Board at the May Assembly of 1848 he oversaw the proclamation of Serbian Vojvodina. His younger brother Stevan was severely wounded and later died of his wounds in Belgrade.[8]

Law career

Law Professor

He returned to Serbia in 1848 and is appointed Professor of Political Science and Civil Law at the Lyceum in Belgrade, he will stay until 1851. Since few textbooks existed, he wrote and printed the Civil Code, the Principles of State Law and the Public Law of Serbia.

Dimitrije Matić and Kosta Cukić were both professors at the Lyceum whose lectures captivated the imagination and spoke to the anxieties of the first self-defined liberal generation. While continuing the tradition of cultivating, on the German model, the "Principles of the Rational State Law; as he entitled one of his major works (1851), Matić took the contrasting of the "legal state" to the "police state" one sizable step further by upholding a Kantian notion of "freedom as legality" personal autonomy and rule of law and demanding a definite check on the state's power to interfere with individual freedom.[1]

Matić was the first to talk about the "people's rights" (narodna prava), such as personal freedom, political and civil rights, which constituted a "natural limit to the state power"; and about popular representation as to the "organ of the people's rights." A constitutional monarchy with a representative body safeguarding the "people's rights" (not sovereignty) was for Matić the "historical" form of the state that stood closest to the "rational idea of the state". Dimitrije Matić and Kosta Cukić texts and lectures helped lay the theoretical foundations of Serbian liberalism as they criticized the existing political system in Serbia. An entire generation of the future leaders of the Serbian liberal movement were their students, most notably Jevrem Grujić, Vladimir Jovanović, and Jovan Ristić.[1]

Three years later, Matić and Cukić were dismissed from their positions because of what was seen as their negative influence on students.[9] Dimitije Matić is transferred into the administration.[10] He became a member of the Court of Cassation, the highest court in the Serbian judicial system. Together with Dimitrije Crnobarac, he was sent by the Serbian government on a mission to Western countries to learn the judicial organization, and especially the procedure in civil disputes, with the aim to shorten and speed up court proceedings in Serbia.[1] On his return he was tasked with drafting the proposal of the first Serbian university; he also worked in the commission proposing new civil procedures.

In 1848 Matić became a member of the Society of Serbian Letters (Društvo srpske slovesnosti), a precursor to the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The society was founded in November 1841 to promote the codification of the modern Serbian language, work on the issue of spelling and spread literacy and teaching throughout the country. King Mihailo suspended the activity of the society in 1864 as he suspected some of its members of using its offices to spread liberal ideas. Dimitrije Matić was an honorary member then a permanent member of the Department of Philology and Philosophy then the committee for the spread of science and literature. Matić's History of Philosophy (1865) and "Encyclopaedia of Science" was written within the framework of the Serbian Learned Society.

Ministerial offices

Upon the return of Miloš Obrenović, Dimitrije Matić is appointed Minister of Education on 3 November 1859, in the Government of Cvetko Rajović.

In that post, he is succeeded by Ljubomir Nenadović. Matić urged the elderly Prince to create a university. Based on the experience he had gained in foreign universities (Berlin, Heidelberg, Paris) and using the Greek example (Athens University founded in 1837), Matić thinks that he has quite a willing pre-condition for starting a university in Serbia, which he proposes to Prince Miloš. At first, Miloš ordered that Matić's project be implemented immediately but suddenly changes his mind, Matić who could not hide his dissatisfaction with the monarch and resigned in protest from his position. After the death of Miloš and the return of Prince Mihailo Obrenović in September 1860, Matić returned to the cassation court in late 1860, staying until 1862.[11] On 10 June 1868 Prince Mihailo is killed and regency is established to rule in 14-year-old Prince Milan's name; in this three-way appointment, Milivoje Blaznavac and Jovan Ristić played the main role. Dimitrije Matić becomes secretary-general of the State Council.

In 1868 Matić became Minister of Education again in the government of Đorđe Cenić then in the government of Radivoje Milojković.

For four years, he was able to organize multiple reforms; opening a higher institution of learning such as Écoles normales supérieures for more advanced education, and the first training college for teachers in the Principality of Serbia, in Kragujevac in 1871. He is also credited for the introduction of physical education in elementary schools when in 1868 he sent a Circular to 207 elementary school teachers recommending them to dedicate 3–4 lessons weekly to gymnastics. Matić increased teachers' s salaries and introduced modern methods of teaching. He was also acting minister of Foreign Affair during the period in the government of Đorđe Cenić then in the government of Radivoje Milojković, in 1872 became a member of the State Council again.

Independence of Serbia

Matlć was a member of the delegation that signed a military alliance with Montenegro, before declaring war on Turkey. After the conflict he is a member of the diplomatic corps that negotiated peace with Turkey on 1 March 1877.

On March 3, 1878, The Peace Agreement of San Stefano did not meet the war plans for the expansion of Serbia and caused the dissatisfaction of the Great Powers, which demanded its revision and call for the Congress of Berlin. Serbia tried to attain support for its independence and territorial expansion within the requested borders from many countries. The attempt of the Serbian government to ensure Italian support at the Congress of Berlin was encouraged by the arrival of Italian volunteers who participated In the armed conflict during 1876. The goal or the diplomatic mission and Dimitrije Matić was to ensure Italian support to Serbia, which the Italian representative In Serbia and the Italian government In resignation also supported. The Serbian Prince opted for diplomatic action in Italy and decided to send Dimitrije Matić to Rome.[12] Matić assessed the audience with King Umberto I as a diplomatic success since he enjoyed all honors and was able to put forward Serbian demands.[13]

In 1878 Dimitrije Matić is elected president of the National Assembly of Serbia, which accepted the provisions of the Treaty of Berlin and recognized Serbia's independence; Serbia acquired almost 4,000 square miles (10,360 km) on its southeastern frontier. Serbia remained a principality until 1882, when it became a kingdom.

Minister of justice

At the new Assembly, elected on October 29, 1878, the liberals got an even more convincing majority; Dimitrije Matić became Minister of Justice in the second government of Jovan Ristić. After the Muslims had left, the question of their property occurred, in many cases, the Turks were the landowners, and the Serbian peasants were tilling the soil and they had to give a certain part of the harvest to the Turks. After the Berlin congress, the Serbian Government decided to give that land to the peasants, for Serbia was a country of free peasant's estates, but before that, a temporary solution was found. All of the Turkish state property, as well as the private land of those Muslims, who tilled it by themselves, had been rented out. The peasants who worked on the Turkish private land had to continue to do so until the final solution was found [14]

According to article 39 of the Berlin treaty, Muslims, who did not wish to live in Serbia, were allowed to keep their property and to rent it to other people. This article disabled the ceding of the land to peasants without any payments to its owners, and the Serbian government did not have enough money to give compensations to the Turks. Therefore, the government and the Assembly had to agree and a special “agricultural law” was passed by which it was decided that the peasants should pay for the land by themselves. Prices and payment conditions were to be established by a free bargain.

The peasants had misused this law in different ways, so the Government was forced to float a loan abroad and to pay off the former landowners[15]

Personal life

Dimitrije Matić was married and had three children:

- Colonel Dr. Stevan Matić (1855–1913)

- Persida Durić married to General Dimitrije Đurić, twice Minister of Defense and professor at the military academy; they had three sons: artillery Captain Milan Đurić (died at the battle of Vranje on March 30, 1911), Miloš and Velizar and four daughters: Stanislava married to Colonel Dr Roman Sondermajer (children: Lt Col Vladislav Sondermajer, aviation pioneer Tadija Sondermayer, Stanislav Sondermayer, the youngest hero of the battle of Cer and daughter Jadviga); Dragica Sajnović married to Vladimir Sajnović, Spasenija "Pata" Marković married to Major Djordje Ristić and Ljubica married to Colonel Mihailo Naumović.

- Jelena Čolak-Antić married to Colonel Ilija Čolak-Antić, commander of the Ibar Army (1836–1894), a descendant of Vojvoda Čolak-Anta Simeonović; they had a daughter, Jovanka and two sons: Boško Čolak-Antić Marshal of the Court under King Peter I and Division General Vojin Čolak-Antić married to Mara Grujić, daughter of prime minister Sava Grujić[8]

Dimitrije Matić died aged 63 on October 17, 1884, in Belgrade.

Published works

Matić was a prolific and eminent writer in Serbian, German and French, his most important work is The Public Law of the Principality of Serbia.

- The Explanation of the Civil Code in three volumes (1850–1851)

- Public Law of the Principality of Serbia (1851)

- His own diary during his studies in Germany entitled "Đački Dnevnik" (Student's Diary, 1845–1848)[16]

- The Principles of Rational State Law according to Heinrich Zoepfl's (1851) (new edition 1995)[17]

- Short Review (according to Hegel's Psychology in Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences)

- Translated "The Science of Education" by Gustav Adolf Riecke in three parts (1866–1868)[18]

- Translated "Machat's Little French Grammar "by Jean Baptise Machat (1854)

- Translated "The History of Philosophy" by Albert Schwegler in two parts (1865)

- Translated "History of Philosophy" by Albert Schwegler

- Translated "Homage to Marcus Aurelius" by Antoine-Léonard Thomas

- Translated "Marcus Aurelius" by Ignaz Aurelius Fessler in three volumes (1844)

See also

- Dimitrije Matic: History of Philosophy, Part 1 (Digital NBS) and Part 2 (in Serbian)

Notes

- a.^ In 1863 when Matić was Secretary-General of the State Council, Captain Miša Anastasijevic donated his magnificent building for the use of education. It is today the University of Belgrade's administration and governance building.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Daskalov 2013, p. 112

- ↑ Serbian Studies 2010, p. 341

- ↑ Milenko 1987, p. 1

- ↑ Zdravko Kučinar. "Facing Europe, but also the Prince". Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Ljusić 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ American Contributions: History, edited by Anna Cienciala Ladislav Matejka, Victor Terras, Anna M. Cienciala Mouton, 1973

- ↑ Rudić 2016, p. 127.

- 1 2 Jovanovic 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ J. Milićević, Јеврем Грујић. Историјат светоандрејског либерализма, Belgrade 1964, pp. 26-35

- ↑ Društvo srpske slovesnosti: Branko Peruničić Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, 1973

- ↑ Летопис Матице српске, У Српској народној задружној штампарији, 1887 - Letopis Matice srpske

- ↑ О Димитрију Матићу - с поводом („Политика“, 3. јул 2010)

- ↑ Rudić, Biagini 2015, p. 50

- ↑ Ibid., p. 49.

- ↑ Jovanović (S.), op.cit. (vol. 2), pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Matić, Dimitrije (1974). "Đački Dnevnik (1845-1848)".

- ↑ Herntrich, Thomas (2010). Thüringen: Von den thüringischen Kleinstaaten nach Zerfall des Alten Reiches bis zum Freistaat Thüringen : Eine völkerrechtliche und verfassungsrechtliche Betrachtung. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631610244.

- ↑ Die wechselseitige Schul-Einrichtung und ihre Anwendung auf Würtemberg. Esslingen: Harburger, 1846 (Digitalisate Bibliothek für Bildungsgeschichtliche Forschung, MDZ München)

Bibliography

- Roumen Daskalov; Diana Mishkova (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Two: Transfers of Political Ideologies and Institutions. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-26191-4.

- Serbian Studies, Volume 16, Issue 2. North American Society for Serbian Studies. 2002.

- Karanovich, Milenko (1987). "Higher education in Serbia during the Constitutionalist regime, 1838-1858, Volume 28 Number 1". Balkan Studies. 28 (1): 125–150.

- Srđan Rudić; Antonello Biagini (2015). Serbian-Italian Relations: History and Modern Times : Collection of Works. Sapienza University of Rome. ISBN 978-86-7743-109-9.

- Milan Jovanovic Stojimirovic (2008). Silhouettes of Old Belgrade (in Serbian). Prosveta. ISBN 978-86-07-01807-9.

- Srđan Rudić; Lela Pavlović (1 September 2016). Serbian Revolution and the renewal of Serbian Statehood (in Serbian). Istorijski institut, Čačak. ISBN 978-86-7743-116-7.

- Rados Ljusic (2005). Government of Serbia: 1805-2005 (in Serbian). Institute for Textbooks and Teaching Aids. ISBN 9788617131119.