The divergence problem is an anomaly from the field of dendroclimatology, the study of past climate through observations of old trees, primarily the properties of their annual growth rings. It is the disagreement between instrumental temperatures (measured by thermometers) and the temperatures reconstructed from latewood densities or, in some cases, from the widths of tree rings in far northern forests.

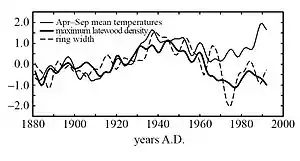

While the thermometer records indicate a substantial late 20th century warming trend, many tree rings from such sites do not display a corresponding change in their maximum latewood density. In some studies this issue has also been found with tree ring width.[2] A temperature trend extracted from tree rings alone would not show any substantial warming since the 1950s. The temperature graphs calculated in these two ways thus "diverge" from one another, which is the origin of the term.

Discovery

The problem of changing response of some tree ring proxies to recent climate changes was first identified through research in Alaska conducted by Gordon Jacoby and Rosanne D'Arrigo.[3][4] Keith Briffa's February 1998 study showed that this problem was more widespread at high northern latitudes, and warned that it had to be taken into account to avoid overestimating past temperatures.[5]

Importance

The deviation of some tree ring proxy measurements from the instrumental record since the 1950s raises the question of the reliability of tree ring proxies in the period before the instrumental temperature record. The wide geographic and temporal distribution of well-preserved trees, the solid physical, chemical, and biological basis for their use, and their annual discrimination make dendrochronology particularly important in pre-instrumental climate reconstructions. Tree ring proxies are essentially consistent with other proxy measurements for the period 1600–1950. Before around AD 1600, the uncertainty of temperature reconstructions rises due to the relative paucity of data sets and their limited geographic distribution. As of 2006, these uncertainties were considered too great to allow conclusion on whether the tree ring record diverges from other proxies during this period.[6] In more recent studies evidence suggested that the divergence is caused by human activities, and so confined to the recent past, but use of affected proxies can lead to overestimation of past temperatures, understating the current warming trend.[2]

Possible explanations

The explanation for the divergence problem is still unclear, but is likely to represent the impact of some other climatic variable that is important to modern northern hemisphere forests but not significant before the 1950s. Rosanne D'Arrigo, senior research scientist at the Tree Ring Lab at Columbia University's Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, hypothesizes that "beyond a certain threshold level of temperature the trees may become more stressed physiologically, especially if moisture availability does not increase at the same time." Signs suggestive of such stress are visible from space, where satellite pictures show "evidence of browning in some northern vegetation despite recent warming."[7]

Other possible explanations include that the response to recent rapid global warming might be delayed or nonlinear in some fashion. The divergence might represent changes to other climatic variables to which tree rings are sensitive, such as delayed snowmelt and changes in seasonality. Growth rates could depend more on annual maximum or minimum temperatures, especially in temperature limited growth regions (i.e. high latitudes and altitudes). Another possible explanation is global dimming due to atmospheric aerosols.[2]

In 2012, Brienen et al. proposed that the divergence problem was largely an artifact of sampling large living trees.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Briffa, K.R.; Schweingruber, F.H.; Jones, P.D.; Osborn, T.J.; Harris, I.C.; Shiyatov, S.G.; Vaganov, E.A.; Grudd, H. (29 January 1998). "Trees tell of past climates: but are they speaking less clearly today?". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 353 (1365): 65–73. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0191. PMC 1692171.

- 1 2 3 D'Arrigo, Rosanne; Wilson, Rob; Liepert, Beate; Cherubini, Paolo (2008). "On the 'Divergence Problem' in Northern Forests: A review of the tree-ring evidence and possible causes" (PDF). Global and Planetary Change. Elsevier. 60 (3–4): 289–305. Bibcode:2008GPC....60..289D. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.03.004. S2CID 3537918. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-19.

- ↑ Jacoby, Gordon C.; D'Arrigo, Rosanne D. (1995). "Tree ring width and density evidence of climatic and potential forest change in Alaska". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 9 (2): 227–234. Bibcode:1995GBioC...9..227J. doi:10.1029/95GB00321. ISSN 1944-9224.

- ↑ Taubes, Gary (1995). "Is a Warmer Climate Wilting the Forests of the North?". Science. 267 (5204): 1595. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1595T. doi:10.1126/science.267.5204.1595. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 2886731. PMID 17808119. S2CID 39083329.

- ↑ Briffa, Keith R.; Schweingruber, F. H.; Jones, Phil D.; Osborn, Tim J.; Shiyatov, S. G.; Vaganov, E. A. (12 February 1998), "Reduced sensitivity of recent tree-growth to temperature at high northern latitudes" (PDF), Nature, 391 (6668): 678, Bibcode:1998Natur.391..678B, doi:10.1038/35596, S2CID 4361534,

D'Arrigo et al. 2008 - ↑ Surface temperature reconstructions for the last 2,000 years. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-309-10225-4.

- ↑ Velasquez-Manoff, Moises (December 14, 2009). "Climategate, global warming, and the tree rings divergence problem". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ↑ Brienen R.J.W.; Gloor E.; Zuidema P.A. (2012). "Detecting evidence for CO2 fertilization from tree ring studies: The potential role of sampling biases". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 26: GB1025. Bibcode:2012GBioC..26B1025B. doi:10.1029/2011GB004143.

External links

- Curiosity Rises With Trees' Strange Growth Spurt, NPR, March 28, 2010