The Doullens Conference was held in Doullens, France, on 26 March 1918 between French and British military leaders and governmental representatives during World War I. Its purpose was to better co-ordinate their armies' operations on the Western Front in the face of a dramatic advance by the German Army which threatened a breakthrough of their lines during the war's final year. It occurred due to Lord Alfred Milner, a member of the British War Cabinet, being dispatched to France by Prime Minister Lloyd George, on 24 March, to access conditions on the Western Front, and to report back.

Background

On 21 March 1918 the Army Groups of the German Empire launched a massive offensive against the British on the Western Front with the strategic aim of defeating the Allies in the West and winning World War I, before the United States of America, which had recently entered the conflict on the Allies' side, could mass enough troops in France to intervene in the conflict. The German spring offensive (Kaiserschlacht or Kaiser's Battle), started with Operation Michael.[1] The commencement of the German offensive was an astonishing success, with the British Fifth Army being initially routed from its trench systems to the point that there appeared to exist the danger as it fell back en masse of it being overwhelmed, risking a breakthrough of the French and British lines on the Western Front by the Germans. The strategic situation was made more unsure for the Allies by a lack of co-ordination between the Commander-in-Chief of the French Armies on the Western Front, General Philippe Pétain, and his peer British Commander, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. Pétain had previously agreed to send six divisions if the British were attacked; these (and more) had been sent, but when Haig requested an additional 20 divisions to support the threatened British 5th Army, Pétain declined, fearing that the attack was a diversionary tactic for an - as yet - undisclosed attack by the Germans upon the French Army.

It became clear in the crisis that better co-ordination between the Allies was needed to prevent a German breakthrough. For this reason, British War Cabinet Minister Lord Milner travelled to France, he met with Georges Clemenceau on the 25th, and he urged the appointment of General Foch to unite the front.[2][3] In the afternoon, the Paris group traveled to Compiegne to make the change official. However, the British generals were meeting at Abbeville (75 miles away), and the two sides could not connect. The Allies decided to meet at Dury town hall on the morning of the 26th, but this was changed to Doullens because Field Marshal Haig had already planned a meeting with his subordinate Army Commanders there. There was a concern that the advancing Germans might actually overrun the town of Doullens before the conference was convened, so close to the front and so precipitous being the German assault, but this didn't happen and it was held there despite being in the path of the oncoming German advance.[4]

Doullens Conference

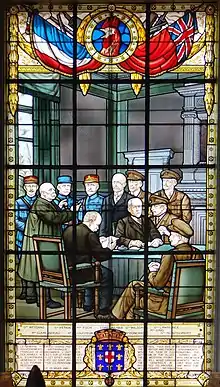

The meeting was held at the Hotel de Ville,[5] its French attendees were General Pétain, French President Raymond Poincaré, Premier Georges Clemenceau, General Ferdinand Foch, General Maxime Weygand, and Minister of Munitions Louis Loucheur. Lord Milner, Field Marshal Haig, and Generals Henry Wilson, Herbert Lawrence, and Archibald Montgomery were the British representatives.[6]

The conference was successful in forming a unified command. It agreed to the creation of an Allied Commander-in-Chief with the power to co-ordinate Allied operations collectively. The members attending the conference believed that General Ferdinand Foch was the most qualified figure for the nature of the role, and placed him in executive charge of co-ordinating the operations of the Allied Armies on the Western Front. One of Foch's remarks at the conference, to give confidence to the British military figures present (who had grave doubts about the willingness of the French to go on with the war) about his qualifications for the role was: "I would fight without a break. I would fight in front of Amiens. I would fight in Amiens. I would fight behind Amiens. I would fight all the time. I would never surrender".[7][8]

The text of the Doullens Agreement can be found in the UK National Archives,[9] and in The Times (of London) newspaper.[10] A copy of the agreement, written by Prime Minister Clemenceau, can be found here.

Lord Milner's complete notes on the meeting can be found in Prime Minister Clemenceau's autobiography.[11]

Controversy

Controversy exists about the Doullens Conference because of various people's claims, but primarily Haig's, that they deserve credit for uniting the Western Front. Upon Lord Milner's return from France on the evening of March 26, he was given official thanks by his peers on the war cabinet.[12] However, he never received public acknowledgment. General Haig says he asked for his two superiors, Lord Milner and General Henry Wilson (CIGS), to come to France and appoint a fighting general like Foch to lead at the Front. Prime Minister Lloyd George says he also asked Milner to go to France. However, no proof can be found of General Haig's claim, although the Prime Minister's claim can be verified. Also, in his war memoirs, Lloyd George published evidence that says General Haig put forward a retreat order to the Channel Ports on March 25, just a day after his supposed request for Foch.[13] The retreat order is verified by General Maxime Weygand, General Foch's chief of staff.[14] Prime Minister Clemenceau mentioned it to Lord Milner the moment Milner arrived at the Doullens Conference, and Milner said he would look into it. Haig told his boss that he was misunderstood, that the order was simply a request for the French to cover his right flank. However, the order is very clear, even mentioning "the Channel Ports" of Dunkirk, Boulogne, and Calais. Orders given to the B.E.F. commander from 1914 gave him the authority to fall back to the Channel Ports if the situation looked hopeless, but not to evacuate.[15] A decision to return to England would be made at a higher level.[16][17] Fortunately, the Doullens decision that appointed General Foch commander of the Western Front nullified any idea of a Dunkirk evacuation in 1918. Later, in early June and with the French facing apparently catastrophic defeat from the German "Bluecher-Yorck" (Chemin des Dames) Offensive, provisional preparations for an evacuation would be begun by Lloyd George,[18] and ended by Lord Milner.[19]

Other, smaller controversies exist with regards to claims made by Lloyd George and General Henry Wilson, and a rumour from French Minister of Munitions Loucher that two Doullens Agreements were written during the conference.

A Secret

_10.jpg.webp)

_4.jpg.webp)

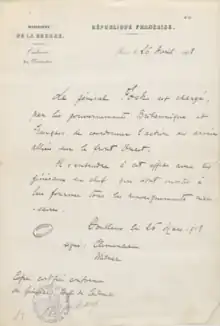

It appears as though the Doullens participants left behind a secret that they all agreed not to discuss. It is commonly understood that the agreement was written by Prime Minister Clemenceau, the civilian leader over the French Army. However, a comparison of handwriting between Georges Clemenceau and Ferdinand Foch shows that Foch was its author. From a legal point of view, an officer cannot write his own promotion order; it must be written by his superior. The situation that early afternoon at Doullens town hall is explained by author Gabriel Terrail:

"Lord Milner asked Prime Minister Clemenceau into the corner of the room and said, 'The British generals accept command of General Foch'. Clemenceau answered, 'Is this a proposal from the government?', to which Lord Milner replied, 'The British government, I guarantee, will ratify what we have decided. Do we agree?' The Prime Minister said, 'We agree...We just need to find a formula that leads to susceptibilities. I’m going to see Foch...Wait for me…'. Clemenceau adds, 'I called Foch, I made him aware of the proposal and I asked him to find the formula necessary to avoid crumpling at Haig and Pétain.' Foch, after half a minute or so of reflection, said to me: 'Here is what one could write: By decision of the Governments of Great Britain and France, General Foch is responsible for coordinating, on the Western Front, the operations of the French and British armies whose commanders-in-chief Marshal Haig and General Pétain, will have to give him all the information useful for the establishment of this coordination'. I approved of this formula, <and> Foch scribbled it down…” [20][21]

Due to the high status and public renown of General's Haig and Pétain, Prime Minister Clemenceau was sensitive to their reaction of General Foch's promotion. This is confirmed by Prime Minister Clemenceau's aide, General Mordacq.[22] Also, Foch knew how to write the order. Even so, the next day:

“On <March> 27th, a commission invited to define the powers given to our chief of staff (Foch had kept his old job, which was not very compatible with that of a field general), Under Secretary of State for War Jeanneney said, “Foch is above Pétain and Douglas Haig to put them <all> in agreement.”[23]

This disagreement set into motion the Beauvais Conference.[24]

A final controversy over General Foch's promotion occurred on April 15. A day earlier, he wrote the following letter to Clemenceau:

“The Beauvais conference on April 3rd gave me sufficient powers to lead the Allied War. They are not known to subordinates, due to indecisions, <and> delays in execution. To remedy this, by my letter of April 5th, I had the honor to ask you to be so kind as to let me know the title I should take in my new duties. I propose that of, “Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies”. As there are no delay in the conduct of operations, please send my request urgently to the English government so that it can respond without delay.”[25]

Foch’s request for a title was immediately approved by both the British and French governments.[26] Prime Minister Clemenceau says the word, "Commander" was a problem for the British (General Haig's title was, "Commander in Chief, British Expeditionary Forces"), so at the suggestion of General Smuts, Foch's title was always translated by the British as "General in Chief".[27][28]

In all of recorded history, only one other general wrote his own promotion order and gave himself a title, and that general was Napoleon Bonaparte. On May 18, 1804, Napoleon declared himself Emperor of France, and in December he crowned himself in front of the Pope and a large audience. Given the historical differences between Britain and France, and the possibility that a French General in overall charge of the Western Front, which included five British Armies, might not be received well by the British people, it is possible that those who attended the Doullens Conference conspired not to tell the entire truth about what took place.

Even respected author B.H. Liddell-Hart said about Foch in 1931, "Like Napoleon at Notre Dame, he was about to crown himself."[29]

Beauvais Conference

A secondary meeting occurred at the French town of Beauvais on 3 April 1918 as a result of the above matter. The end agreement addressed a commander in chief's (General's Haig, Pétain, Pershing, Albert (Belgium), and Diaz's (Italy)) right to protest an order that he felt threatened his army. General Tasker Bliss, senior military representative of the United States of America's Supreme War Council was present at this meeting to give the United States' assent to the candidature of Foch for the post.[30] As mentioned, General Foch's title was addressed on April 14, 1918, after he wrote to Prime Minister Clemenceau.[31] It was approved by the British War Cabinet the following day.[32]

The text of the Beauvais Agreement can be found in the UK National Archives.[33]

The Second Abbeville Conference

This was the fifth Supreme War Council meeting held on 1–2 May 1918 in the French town of Abbeville, France. In January 1918, the allies agreed to meet once a month to discuss war strategy. Its purpose was to resolve the Allies' reinforcement troop shortages in the fourth year of the war. The French and the British were by this late stage of the conflict struggling to meet the numbers for the maintenance of the war, and requested of the American representatives present an escalation of that country's plans for the shipment its troop formations across the North Atlantic Ocean to assist with making up the shortfall.[34] At this meeting, the allies agreed to modify "The London Agreement" signed by Lord Milner and General Pershing just a week earlier, in order to ramp up the shipment of American troops to France.

Also at this conference Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando consented to General Foch's (as the new 'Allied Commander-in-Chief') authority extending to the Southern European theatre front in North Italy, to facilitate co-ordination of the Italian Army's operations there with those taking place on the Western Front in France and Belgium.

On May 2, Prime Minister Lloyd George had all the generals meet at the Prefect's house in Abbeville to discuss war strategy. It was found that in a crisis both General's Wilson and Haig supported a retreat north toward the Channel Ports. Others supported an advancement south, sacrificing the ports in favor of linking up with the French and continuing the war.[35] It was decided that foregoing embarkation and maintaining a link with the French would be the policy.[36] On 21 June 1918, the B.E.F. Commander's instructions were updated to order him in the time of crisis to advance southward and maintain contact with the French army at all costs.[37]

Footnotes

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts, and John S. D. Eisenhower, World War I: A Student Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2005), 587

- ↑ Amery, Leo, "My Political Life, Vol II", London: Hutchinson, 1953, pg. 147

- ↑ Callwell, C.E., "Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries, Vol. II", pg. 76

- ↑ Rod Paschall, Colonel Rod Paschall, and John S. D. Eisenhower, The Defeat of Imperial Germany 1917-1918 (Da Capo Press, 1994), 144

- ↑ 'Doullens on parade for Foch centenary', World War I 'Centenary News' website (1919). https://www.centenarynews.com/article/doullens-on-parade-for-foch-centenary

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts, and John S. D. Eisenhower, World War I: A Student Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2005), 588

- ↑ Clemenceau, Georges, "Grandeur and Misery of Victory", pg. 36

- ↑ Samuel Lyman Atwood Marshall, World War I (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001), 357

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 23-5, pg. 396 of 475

- ↑ The Times, May 22, 1928, pg. 16

- ↑ Clemenceau, Georges, "Grandeur and Misery of Victory", New York: Harcourt Brace, 1930, pgs. 407-423

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 23-5, pg. 397 of 475

- ↑ Lloyd George, David, "War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, Vol. V, 1917-1918", Boston: Little Brown, 1936, pgs. 387 & 388

- ↑ Weygand, Maxime, "Memoires, Vol I", France: Flammarion, 1953, pgs. 276-280

- ↑ Cooper, Duff, "Haig, The Second Volume", London: Faber and Faber, 1936, pgs. 451-454

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin, "Winston S. Churchill, Vol. IV, 1917-1922", pg. 80

- ↑ Wright, Peter E., "At The Supreme War Council", pgs. 124-125

- ↑ X Committee Minutes, CAB-23-17 pgs. 46-47 of 206

- ↑ Amery, pg. 158

- ↑ Terrail, Gabriel, "The Unique Command", pgs. 212 & 213 (translated from french)

- ↑ Wright, pg. 142

- ↑ Mordacq, Henri, "Unity of Command: How it Was Achieved", pg. 79

- ↑ Ibid., pg. 213

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 23-6, pg. 8 of 457, minute 2

- ↑ Marshall-Cornwall, Sir James, “Foch as Military Commander”, New York: Crane, Russak, 1972, Appendix II

- ↑ CAB 23-6, pg. 72

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 23-14, pgs. 40, 41

- ↑ Woodward, David, "Lloyd George and the Generals", pg. 295

- ↑ Liddell-Hart, B.H. "Foch, The Man of Orleans", pg. 274

- ↑ Jehuda Lothar Wallach, Uneasy Coalition: The Entente Experience in World War I (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1993), 114

- ↑ Cornwall-Marshall, Appendix II

- ↑ National Archives, CAB 23-6, pg. 72 of 457, minute 12

- ↑ Ibid., pg. 18

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, Laura Matysek Wood, and Justin D. Murphy, The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (Taylor & Francis, 1996), 1

- ↑ Lloyd George, David, "War Memoirs", Vol VI, pgs. 41-42

- ↑ Callwell, Vol II, Pg. 98

- ↑ Cooper, pgs. 451-454

References

- Amery, Leo, "My Political Life, Vol II" London: Hutchinson, 1953

- Clemenceau, Georges, "Grandeur and Misery of Victory", New York: Harcourt Brace, 1930

- Gilbert, Martin, "Winston S. Churchill, Vol, IV, The Stricken World" 1917-1922, London: Heinemann, 1975

- Lloyd George, David (1936), War Memoirs Of David Lloyd George, vol. 5 (New ed.), Boston: Little, Brown

- Lloyd George, David (1937), War Memoirs Of David Lloyd George, vol. 6 (New ed.), Boston: Little, Brown

- Terrail, Gabriel, "The Unique Command", Paris: Literary & Artistic Co., 1920 (translated from french)

- Weygand, Maxime, "Memoires, Vol I", France: Flammarion, 1953 (translated from french)

- Marshall-Cornwall, Sir James, “Foch as Military Commander”, New York: Crane, Russak, 1972

- Cooper, Duff, Haig, The Second Volume, London: Faber and Faber, 1936

- Tucker, Spencer, & Priscilla Mary Roberts, and John S. D. Eisenhower, "World War I: A Student Encyclopedia", unknown: ABC, 2005

- Paschall, Rod, & Colonel Rod Paschall, and John S. D. Eisenhower, "The Defeat of Imperial Germany 1917-1918", unknown: Da Capo Press, 1994

- Marshall, Samuel Lyman Atwood, "World War I", unknown: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001

- Centenary News, "Doullens on parade for Foch centenary", 'Centenary News' website, 1919

- Tucker, Spencer, & Laura Matysek Wood, and Justin D. Murphy, "The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia", unknown: Taylor & Francis, 1996

- Wallach, Jehuda Lothar, "Uneasy Coalition: The Entente Experience in World War I" unknown: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1993

- Mordacq, Henri, "Unity of Command: How it Was Achieved", Paris: Tallandier, 1929 (translated from french)

- Callwell, MG C.E., Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries, Vol II, London: Cassell, 1927

- Wright, Peter, At The Supreme War Council, New York: G.P. Putnam, 1921

- Woodward, David R., "Lloyd George and the Generals", Newark, DE: University of Delaware, 1983

- Liddell-Hart, B.H., Foch, The Man of Orleans, Boston: Little Brown, 1931

Further reading

- Edmonds, James, History of the Great War, Military Operations in France and Belgium, 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries, Vol VII, London: Macmillan, 1935, (Doullens: pgs. 538-549)

- Foucart, Pierre, Doullens: The Room of Single Command