Druce & Co. were a British furniture manufacturer and antique dealers operating in the 19th and 20th century. The company was founded by Thomas Charles Druce (b.1761 - d.1864) in the 1840s and was based in Baker Street and Portman Square, London.[1] During the 19th century, Druce expanded into a department store and an estate agency.

Today Druce specialises in prime residential property, and functions solely as an estate agency. The company maintains an office in Marylebone, and several additional locations in Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill, Brook Green, Kensington and Chelsea - the result of its acquisition of Bective Estate Agency.

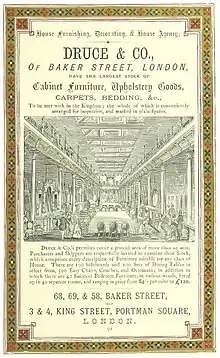

Advertisement for Druce & Co. | |

| Industry | Furniture manufacturer |

|---|---|

| Founded | c.1840 |

| Founder | Thomas Charles Druce |

| Headquarters | 68 Baker Street, Portland Square, London |

History

.jpg.webp)

The company was based at 68, 69 & 58 Baker Street in a premises known to contemporaries as The Baker Street Bazaar. Originally a horse and carriage market, the Bazaar became one of the most grand general retail markets in Victorian London. It also became an exhibition site and was host to the famous Madame Tussauds waxwork exhibitions.[2]

In 1825 a furniture department was installed on the upper floor of the bazaar and in 1838 this expanded further to include a workshop. In 1843 the auction-room of the bazaar was converted into a furnishing ironmongery called the Panklibanon (also written as Panclibanon) which made items for the home including fireplaces, stoves and bathtubs.[2][3]

Thomas Charles Druce was a draper and upholsterer in Regent Street before he acquired control of the bazaar's furniture department in the 1840s.[4] Under his management the department grew in size and popularity and in the 1883 edition of A Dictionary of Common Wants Druce & Co. are cited as viable sources for numerous goods. Druce's entry in the furniture section reads:

"MESSERS DRUCE & CO., have one of the most varied and extensive stocks in the Kingdom. They are manufacturers of the whole of the goods they supply, and are therefore in the position to guarantee the quality of the materials used."[5]

After his death, the operation of the business was taken over by Thomas' son, Herbert Druce, from 1864 until 1913.[6][7]

Second World War and decline

The premises was severely damaged in an air raid during December 1940 and the site was demolished in 1941 and rebuilt. Druce's department store and auction rooms closed in the 1950s and today only the estate agency faction still continues to operate.[4]

The site was taken over by supermarket chain Marks & Spencer in 1957 where it became the company's head office. It was their headquarters until 2005 when the premises was sold to London & Regional Properties for £115 million.[8]

The Druce-Portland affair

The Druce-Portland affair (also referred to as the Druce Case) occurred during the early years of the twentieth century. After Thomas Druce's death in 1864, his daughter-in-law Anna Maria Druce (second wife to Druce's son Walter Druce) voiced claims that her father-in-law was leading a double life. She claimed that he was not the furniture retailer Thomas Charles Druce but rather that this was an alter ego and that he was really John Bentinck, the 5th Duke of Portland. If this claim were true it would mean that the now widowed Anna Maria was heir to the Portland fortune and would inherit the ducal titles and wealth of the Portland family.[9]

.jpg.webp)

The case brought with it a great amount of public controversy and became a cause célèbre of late 19th century London. Anna campaigned for an exhumation of Druce's coffin and suggested that because Druce had supposedly faked his own death his body would not be there and the coffin would be empty.

The affair attracted other claimants from around the world and in 1903 George Hollamby Druce arrived in England from Australia. G. H Druce was the son of George Druce and the grandson of T. C Druce and therefore also brought with him legal claims to the Portland estate. These claims led to the Druce v. Howard de Walden case in 1906 against the daughters of the current 4th Duke of Portland.[9][10] In order to finance their claims and spread their message, the claimants of the Druce family published their own sensational pamphlets. One published by Anna Maria herself was titled 'The Great Druce-Portland Case' (1898).[11]

After a years of campaigning, the court ruled in Anna's favour and on 29 December 1907 work was begun to move the 3 tonne stone monument which marked Druce's resting place.[12] The coffin was opened and Druce's body was found intact and the case promptly collapsed. Some of the litigants were convicted of perjury and Anna Maria Druce was committed to a mental hospital where she would spend the rest of her life.[9]

The incident gained international fame and the story was printed in newspapers including The Los Angeles Herald and The New York Times.[12][13]

A fictionalised version of the Druce-Portland affair is the subject of Tom Freeman Keel and Andrew Crofts' The Disappearing Duke: The Improbable Tale of an Eccentric English Family (2003).[14]

See also

External links

- Druce estate agents

- The Innholder's Company

- Bonham's antiques - Davenport desk by Druce & Co.

- Sotheby's - bureau by Druce & Co.

- The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1789)

References

- ↑ "Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- 1 2 Morrison, Kathryn (2006). "Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London" (PDF). The Georgian Group. 15: 281–308.

- ↑ Panclibanon Iron Works: 58, Baker Street, Portman Square, London. Shaw. 1850.

- 1 2 "Thomas Charles Druce | UCL The Survey of London". blogs.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ↑ A dictionary of common wants. 1773. p. 23.

- ↑ "English Cabinet Makers - A to Z. - Antiques World". Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Victorian Burr Walnut 'piano Top' Davenport By Druce & Co. | 289185 | Sellingantiques.co.uk". www.sellingantiques.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "M&S sells Baker St HQ for £115m". the Guardian. 4 February 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 Darroch, Sandra Jobson (2017). Garsington Revisited: The Legend of Lady Ottoline Morrell Brought Up-to-Date. Indiana University Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-0-86196-737-7. JSTOR j.ctt2005v1f.

- ↑ "Search Results - Manuscripts and Special Collections Online Catalogue - The University of Nottingham". mss-cat.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "The Druce Case - The University of Nottingham". www.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- 1 2 "Open Grave to Find Body of T.C. Druce". The Los Angeles Herald. 30 December 1907. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "Druce Coffin Holds a Body, Not Lead". The New York Times. 31 December 1907. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ Freeman-Keel, Tom; Andrew, Crofts (6 February 2003). The Disappearing Duke: The Improbable Tale of an Eccentric English Family. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-1045-4.