54°8′35″N 7°18′35″W / 54.14306°N 7.30972°W

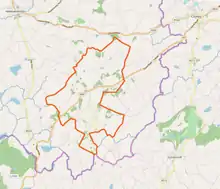

Drummully or Drumully (Irish: Droim Ailí;[1] "rocky ridge"[2]) is an electoral division (ED) in the west of County Monaghan in Ireland. Known as the Sixteen Townlands[3][4] to locals and as Coleman's Island[5] or the Clonoony salient[6] to the security forces, it is a pene-enclave almost completely surrounded by County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. Since the Partition of Ireland in the 1920s, the Fermanagh–Monaghan border has formed part of the international border between the United Kingdom and what is now the Republic of Ireland, leaving Drummully as a practical enclave, connected to the rest of the republic only by an unbridged 110-metre (360 ft) length of the Finn River.[5][7] The area is accessed via the Clones–Butlersbridge road, numbered N54 in the Republic and A3 in Northern Ireland.

The civil parish of Drummully includes the Monaghan ED and the surrounding parts of Fermanagh; the townland of Drummully, with the ruins of the medieval parish church, lies in the Fermanagh portion of the parish.[2] The two county Fermanagh EDs separating Drummully from the republic are Clonkeelan to the east and Derrysteaton to the southwest.[8] The Connons is a name given sometimes to Drummully ED,[5][9] and sometimes to the entire district between Clones and Redhills, County Cavan, encompassing Clonkeelan, Drummully, and Derrysteaton.[4][8][10] Connons Catholic church and Connons community hall are in Drummully ED.

History

The area's unusual border was ascribed in the 1920s to "some long forgotten feud between petty kings".[3] Drummully ED lies in the province of Ulster near the tripoint of three counties, Monaghan, Fermanagh, and Cavan, which were created in the 1580s from three medieval Gaelic lordships: respectively Airgíalla (McMahon's country), Fear Manach (Maguire's country) and East Breifne (O'Reilly's country). These lordships had been divided into túatha, subdivided into bailte biataigh ("ballybetaghs") and "tates". In the 15th century the Mac Domhnaill (MacDonnells[n 1] or MacDonalds) were former rulers of the túath of Clann Ceallaigh, allied to the McMahons of the túath of Dartraighe to the southeast, and pressed by Maguire expansion from the northwest. The Mac Domhnaill were gradually concentrated in the ballybetagh of Ballyconinsi,[12][n 2] whose extent corresponds with that of Drummully ED.[14] Coininse "Hound Island" is the origin of [the] Connons and Ballyconinsi (baile + Coininse); according to Nollaig Ó Muraíle, it is unclear precisely where the island is or was;[15][16] John O'Donovan said in 1848 that it was a townland "now divided into several sub-denominations".[17] Most of the 16 townlands now in the Drummully ED can be identified among the 16 tates listed in the ballybetagh of Ballyconinsi in records of 1591, 1606, and 1610.[12][18][13]

The Tudor conquest of Ireland proceeded by surrender and regrant, whereby a Gaelic lord would surrender sovereignty to the English monarch as monarch of Ireland, and be regranted title to the land under common law. The 1580s shiring of Ulster proceeded on that basis, with McMahon's country becoming County Monaghan, within which Dartraighe became the barony of Dartree; likewise Clann Ceallaigh became Clankelly barony in County Fermanagh. Ballyconinsi was shired with the McMahons rather than their enemies the Maguires.[12][19] Most of the Gaelic proprietors in these counties forfeited their lands after the Nine Years' War or the Rebellion of 1641.[12] In 1640, most of Ballyconinsi was owned by one Jacob Leirrey, with small tracts retaining Gaelic owners.[20]

Until 1836, a change to the 1580s boundaries would have required an Act of the Irish Parliament (to 1800) or the UK Parliament (1801–1922). While the Valuation of Lands (Ireland) Act 1836 facilitated transfer of exclaves (as of Gubdoo from Dartree to Coole, County Fermanagh in 1842[21]) it did not apply to pene-exclaves. EDs were introduced with the Irish Poor Law Act of 1838 as electoral areas for the boards of guardians of the new Poor Law Unions (PLUs); Drummully ED was within Clones PLU and initially included most of the parish of Drummully, but in 1877 it was redrawn with its current boundaries.[22] The Local Government Board for Ireland was empowered to adapt county boundaries for the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, but Drummully was left unchanged, and elected two councillors by plurality block voting to Clones No. 1 rural district council (RDC). In the 1911 local elections, all seats in Clones No. 1 were uncontested except for Drummully, where the vote count was: John Winters (Nationalist, outgoing) 48; John Murtagh (Nationalist, outgoing) 47; James Hyde (Unionist) 47; Thomas Nesbitt (Unionist) 47. Hyde won the second seat by lot.[23] Drummully ED was last used as an electoral area in the 1914 local election.[24] The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1919 mandated the single transferable vote, which needed multi-seat local electoral areas (LEAs) formed by combining single-seat EDs.[25] Since then, EDs have no independent uses but remain legally defined areas used as references for specifying the makeup of larger units,[26] or the location of smaller ones.[27]

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 attempted to answer the "Irish question" within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, by grouping the counties into separate home rule jurisdictions of Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, with Fermanagh in the former and Monaghan in the latter. Irish republican opposition saw the 1920 act superseded by the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, with Southern Ireland being replaced by a dominion called the Irish Free State and the provisional border with Northern Ireland subject to change by an Irish Boundary Commission. Protestant unionists owned most of the land in Drummully but were a minority of the population.[28] Submissions to the boundary commission from unionists (including Fermanagh County Council and the Church of Ireland parish of Drummully) proposed to resolve the inconvenience of the locality's sinuous border by transferring Drummully ED to Northern Ireland,[29] while those from nationalists (including Clones urban district council and the Free State government) proposed transferring all, or at least adjoining parts, of Fermanagh to the Free State.[30] Nationalist and unionist locals both submitted that they would rather the area were entirely on the "wrong" side of the border than preserve the status quo.[31] The commission's 1925 report proposed straightening the border by transferring Drummully ED's northernmost 14% (336 acres (136 ha); population 51) to Northern Ireland, and 18,623 acres (7,536 ha) (population 3,808) of adjoining Clonkeelan and Derrysteaton EDs from Fermanagh to the Free State.[32] The Clones–Butlersbridge road, the Ulster Canal, and the railway line between Clones and Redhills would each have been entirely south of the border instead of crossing it four times (the canal forming the border for several hundred yards).[33] However, the report as a whole proved so controversial that publication was suppressed and it was never implemented.[34]

Drummully was inaccessible by road except through the United Kingdom. It was not policed until May 1924 when the Garda Síochána were allowed to pass through Northern Ireland, by which time poteen making was rife.[35] The Church of Ireland parish of Drummully had its rectory in the north and its church in the south; for some years after partition, marriages solemnised there were not registered with the Dublin authorities.[3] There were customs posts at the main Irish border crossings, but none around Drummully: the N54/A3 was a "concession road" such that journeys beginning and ending in the same jurisdiction did not require any border formalities, while the other crossings were "unapproved roads" where spot checks on traffic might confiscate transported goods presumed to be smuggled.[36] The border runs down the middle of a minor road in the north of Drummully.[7] The Royal Ulster Constabulary during the IRA "border campaign" of the 1950s, and the British Army from 1971 during the Troubles, blocked the unapproved roads into Drummully with reinforced concrete blocks, metal spikes and craters, to prevent the area being used as a redoubt by Irish republican paramilitaries.[36] The Dublin government gave the British military permission, renewed annually, to overfly the area "to facilitate the transport of men and materials, the evacuation of casualties and, in particular, the shadowing of suspect vehicles".[6] Irish security forces were not permitted to travel through Northern Ireland in uniform,[37] and "[t]he only route for armed gardai or army would appear to be by helicopter",[37] using the Irish Air Corps helicopter based at Monaghan town.[38] Local TD Jimmy Leonard complained in 1974 of concomitant lawlessness,[39] while in 1980 there were fears that the Air Corps helicopter might be shot down by republicans mistaking it for an RAF aircraft.[40] These blockages were removed by the 1990s peace process. Since then, the post-1992 European Single Market and the post-1952 Common Travel Area between Ireland and the UK have made the border "invisible". Nevertheless, when 2010 budget cuts deprived Clones Garda station of its unmarked car, officers could no longer drive to Drummully.[41]

The prospect of Brexit has uncertain impact on the border; an "Irish backstop" to preserve an invisible border was included in the November 2018 Brexit withdrawal agreement which the UK parliament rejected in 2019; the October 2019 agreement includes a similar arrangement, subject to ratification by Westminster, subsequent EU–UK implementation agreements, and possible future termination by cross-community vote of the Northern Ireland Assembly.[42] International coverage of Brexit has often mentioned Drummully as a place especially sensitive to these issues.[43]

Statistics

| Name[44] | Area[45] | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ac |

ha |

1841 [46] |

1911 [45] |

2016 [47][48] | |

| Annaghraw | 112 | 45 | 87 | 39 | [n 4] |

| Clonfad | 248 | 101 | 142 | 46 | 0 |

| Clonkeelan | 230 | 93 | 169 | 35 | 9 |

| Clonlura | 137 | 55 | 108 | 42 | 17 |

| Clonnagore | 166 | 67 | 102 | 46 | 22 |

| Clonnestin | 173 | 70 | 115 | 24 | [n 4] |

| Clonoony | 213 | 86 | 86 | 37 | [n 4] |

| Clonoula | 236 | 95 | 131 | 36 | 7 |

| Clonrye | 78 | 32 | 89 | 12 | 0 |

| Clonshanvo | 101 | 41 | 56 | 20 | [n 4] |

| Clontask | 84 | 34 | 47 | 10 | [n 4] |

| Coleman | 166 | 67 | 65 | 23 | [n 4] |

| Corvaghan | 170 | 69 | 89 | 28 | [n 4] |

| Derrybeg | 54 | 22 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Drumsloe | 122 | 49 | 178 | 23 | 18 |

| Roranna | 136 | 55 | 80 | 25 | [n 4] |

| Total | 2,377 | 962 | 1,552 | 449 | 113 |

| [n 5] | |||||

| Date | Pop. | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 1,552 | [46] |

| 1851 | 946 | |

| 1861 | 957 | |

| 1871 | 744 | |

| 1881 | 661 | [49] |

| 1891 | 595 | |

| 1901 | 537 | |

| 1911 | 449 | [50] |

| 1926 | 390 | |

| 1936 | 366 | [51] |

| 1946 | 346 | |

| 1951 | 326 | [52] |

| 1956 | 279 | |

| 1961 | 221 | [53] |

| 1966 | 194 | |

| 1971 | 160 | [54] |

| 1979 | 140 | |

| 1981 | 128 | |

| 1986 | 131 | [55] |

| 1991 | 120 | |

| 1996 | 98 | [56] |

| 2002 | 102 | [57] |

| 2006 | 92 | |

| 2011 | 98 | [47] |

| 2016 | 113 | |

| 2022 | 136 | [58] |

Footnotes

- ↑ Not to be confused with the Scottish MacDonnells who came later as gallowglasses.[11]

- ↑ Also spelt Balleneconnishe,[13] Bellacunnedge, Balleconyushe, Ballycovench, or Ballycovenghe.[12]

- 1 2 These tables relate to the 16 townlands which have been in Drummully ED since 1877; before then 8 of the townlands were in Clonkeelan ED, while Drummully ED contained 23 townlands in Fermanagh.[22]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Population of either two people or one gender, not stated for privacy.

- ↑ Total area of 962 ha is from 2016 census.[47] The townland areas from the 1911 census total 2424 ac 3 r 13 p (981.29 ha).[45]

References

Citations

- ↑ "Drummully". Logainm.ie. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- 1 2 "Drummully, County Fermanagh". Place Names NI. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 Leary 2016 pp.31–35

- 1 2 Kelly, Tom (12 August 2009). "Rededication of Connons church". Anglo Celt. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 McNally, Frank (18 September 2013). "Borderline Nationality Disorder". The Irish Times. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 Department of Foreign Affairs (25 July 1977). "TSCH 2007/116/757: Memorandum for the Government: Overflights by Foreign Military Aircraft" (PDF). Dublin: NAI Public Records. p. 4 no.6. Retrieved 27 March 2020 – via CAIN.; Collins, Stephen (28 December 2007). "Lynch allowed British military overflights". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- 1 2 Jennings, Ken (21 November 2016). "Ireland's Drummully Polyp Is Not a Sea Cucumber—It's an Island". Conde Nast Traveler. Conde Nast.

- 1 2 "The Boundaries of Administrative Counties, Co. Boroughs, Urban & Dispensary Districts & District Electoral Divisions; north-east sheet" (JPEG). Logainm.ie (revised ed.). Dublin: Ordnance Survey of Ireland. 1962 [1935].

- ↑ Muhr, K (2004). "The place-names of County Fermanagh". In Murphy, Eileen M.; Roulston, William J. (eds.). Fermanagh: history and society: interdisciplinary essays on the history of an Irish county. Geography Publications. p. 586. ISBN 9780906602522.

- ↑ "President emphasises importance of community during Clones visit". Northern Standard. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Mr Conlon described Connons as having a unique formation as it straddles the border with one third of it located in Co Monaghan and two-thirds of it in Co Fermanagh.

- ↑ Ó Gallachair, P. (1974). "Clogherici: A Dictionary of the Catholic Clergy of the Diocese of Clogher (1535-1835) (Continued)". Clogher Record. 8 (2): 207–220. doi:10.2307/27695699. JSTOR 27695699.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schlegel, Donald M. (2005). "MacDomhnaill Clainn Ceallaigh". Clogher Record. 18 (3): 437–466. doi:10.2307/27699524. ISSN 0412-8079. JSTOR 27699524.

- 1 2 Chancery, Ireland (1800). "Pat 8 James I recto XXIV". Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland. Dublin. p. 172. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ Duffy 2012 Fig.1

- ↑ Lehmacher, Gustav (1923). "Eine Brüsseler Handschrift der Eachtra Conaill Gulbain". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie (in German and Irish). 14 (1): 218. doi:10.1515/zcph.1923.14.1.212. S2CID 161944880. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

ocus for Dartraighe Coninse // und über Dartraighe Coininse (D. von der Hundsinsel)

- ↑ Muraíle, Nollaig Ó (1984). "The Barony-Names of Fermanagh and Monaghan". Clogher Record. 11 (3): 387–402: 398 fn.69. doi:10.2307/27695897. ISSN 0412-8079. JSTOR 27695897.

- ↑ O'Donovan, John, ed. (1848). Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland. Vol. III. Dublin: Hodges and Smith. p. 1876, fn. f. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑

- "Survey of Com. Monaghan — A.D. 1591". Inquisitionum in Officio Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Asservatarum Repertorium. Vol. II. Dublin: His Majesty's Printers by command. 1829. pp. xxix–xxx. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Townlands in Drummully, co. Monaghan". Logainm.ie. for each townland listed, under "Scanned records". Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ Moore, Philip (1955). "The Mac Mahons of Monaghan (1500-1593)". Clogher Record. 1 (3): 22–38: 27, 31. doi:10.2307/27695412. ISSN 0412-8079. JSTOR 27695412.; Cunningham, Bernadette; Gillespie, Raymond (2003). "The burning of Domnach Magh da Claine: church and sanctity in the diocese of Clogher, 1508". Stories from Gaelic Ireland: microhistories from the sixteenth-century Irish annals. Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851827473.

- ↑ Duffy 2012, Figs 5 and 6

- ↑ "County (Ireland); (g) Donegal; Proclamation in Council, dated February 9, 1842, as to Boundaries of Counties of Donegal, Fermanagh, and Monaghan.". The Statutory Rules and Orders Revised, being the Statutory Rules and Orders (Other Than Those of a Local, Personal Or Temporary Character) in force on December 31, 1903. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. 1904. p. 33. Retrieved 27 August 2019.; "III. County tables; Ulster; Fermanagh; I. General table". Census of Ireland, 1841. Alexander Thom for HMSO. 1843. p. 331, fn. Retrieved 27 August 2019 – via www.histpop.org.

- 1 2 Census of Ireland 1881; Part I; Volume III: Ulster. HMSO. 1882. 769 fn (d) and p.587 fn (c). Retrieved 29 August 2019.; Return of Poor Law Unions in Ireland, showing Names of Townlands. Parliamentary Papers. Vol. HC 1864 LIII (377) 97. HMSO. 10 June 1864. pp. 129–130. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ "Irish Local Elections ; Clones No. 1 Rural District". Belfast Weekly Telegraph. 3 June 1911. p. 4 c. 4. Retrieved 27 September 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Geary Institute, University College Dublin (November 2008). "Preliminary study on the establishment of an Electoral Commission in Ireland" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. p. 21. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

obsolete units in rural areas (electoral divisions, last used for administrative purposes in the local elections of 1914)

- ↑ Local Government Board for Ireland (1921). [Forty-eighth] Annual Report [for year ending 31st March 1920]. Command papers. Vol. Cmd.1432. Dublin: HMSO. pp. ii–vii, Appendix p.38. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ↑ e.g.:

- S.I. No. 468/2013 for "The closure of the District Court Area of Clones and the amalgamation of its Electoral Divisions [including Drummully] into the District Court Area of Monaghan"

- S.I. No. 629/2018 Drummully ED included in Ballybay–Clones LEA.

- ↑ e.g.:

- S.I. No. 54/2015 "The areas ... listed in Column 2 of the Schedule to these Regulations, located in the Electoral Divisions and Local Electoral Areas listed in Columns 3 and 4 of the said Schedule, opposite the mention of the relevant administrative county in Column 1 of the said Schedule are hereby prescribed to be urban areas for the purposes of the Derelict Sites Act, 1990. ... [including] Drumsloe [townland] in Drummully [ED] in Ballybay — Clones [LEA]"

- ↑ Dooley, Terence A. M. (2000). The Plight of Monaghan Protestants, 1912–26. Irish Academic Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 9780716527251.

- ↑ Irish Boundary Commission and Hand 1969, pp. 21, 101

- ↑ Irish Boundary Commission and Hand 1969, pp. 21–22, Appendix III p. 51

- ↑ Moore, Cormac (29 September 2019). Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland. Merrion Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1785372933.

- ↑ Irish Boundary Commission and Hand 1969, pp. 102–103, 110; Appendix V pp.90–92; map "North Eastern Ireland showing complexion by Religions, Census 1911"

- ↑ Irish Boundary Commission and Hand 1969, p. 149

- ↑ Irish Boundary Commission and Hand 1969, pp. xx–xxi

- ↑ Livingstone, Peadar (1980). The Monaghan story: a documented history of the County Monaghan from the earliest times to 1976. Clogher Historical Society. p. 396.

- 1 2 Leary 2016 pp.172–177

- 1 2 Dooley, Terence A. M. (1994). "From the Belfast Boycott to the Boundary Commission: Fears and Hopes in County Monaghan, 1920–26". Clogher Record. 15 (1): 90–106: 97. doi:10.2307/27699379. ISSN 0412-8079. JSTOR 27699379.

- ↑ King, B. M. (October 1990). "Green with Blue - Operating in Cavan/Monaghan Division" (PDF). An Cosantóir. 50 (10): 14–15: 15. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ↑ Leonard, James (7 March 1974). "Committee on Finance — Vote 20: Office of the Minister for Justice (Resumed)". Dáil Éireann (20th Dáil) debates. Oireachtas. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ Faulkner, Pádraig (15 May 1980). "Questions. Oral Answers. - Border Roads". Dáil Éireann (21st Dáil) debates. Houses of the Oireachtas. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ Reilly, Gavan (21 November 2011). "Monaghan villagers left beyond the law by Garda cutbacks". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Lisa. "How is Boris Johnson's Brexit deal different from Theresa May's?". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ↑ McQuade, Owen; Galway, Ciarán; Whelan, David (29 November 2017). "Voices from the border". Eolas Magazine. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

The Connons area has been the subject of global media interest since Article 50 was triggered.

; "Locals fear being cast away on Brexit border 'island'". France 24. Agence France Press. 16 October 2018.; "Brexit angst in the Irish border town of Drummully Polyp". msn.com. DW News. 28 September 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.; "Feature: Border residents waiting in confusion for Brexit results". Xinhua. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019. - ↑ "Townlands in Drummully". Logainm.ie. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- 1 2 3 Census returns for Ireland, 1911. Vol. Province of Ulster. HMSO. 1913. p. 1119. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- 1 2 Census of Ireland 1871 : Part I, Area, Population, and Number of Houses; Occupations, Religion and Education. Vol. III, Province of Ulster, Summary Tables, Indexes. HMSO. 1874. p. 781. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Sapmap Area: Electoral Division Drummully". Census 2016. CSO. Retrieved 29 August 2019.; "Population Density and Area Size 2011 to 2016 by Electoral Division, CensusYear and Statistic". StatBank - data and statistics. CSO. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ "Small Area Population Statistics". Census 2016. Cork: Central Statistics Office. Census 2016 population for 50,117 Townlands. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ↑ "Table VII: Area,... and Population ... of each ... Townland ...". Census of Ireland 1901; Part I: Area, Houses, and Population v.3: Ulster; No.8, Monaghan. Command papers. Vol. Cd. 1123—7. 1902. p. 21.

- ↑ "Census 1926 v.1 p.129 Table 11."

- ↑ "Census 1946 v.1 p.128 Table 11. Population, Area and Valuation of each District Electoral Division, Urban District, and Rural District and County of Ireland (excluding the six North-Eastern Counties) at the 12th May, 1946"

- ↑ "Census 1956 v.1 Table 11. Population, area and valuation of each district electoral division, urban district, rural district and county of Ireland at the 8th of April 1956. p.135 Monaghan No.41"

- ↑ "Census 1966 v.1 Table 11. Population, area and valuation of each district electoral division urban district, rural district and county p.143 Monaghan No.41"

- ↑ "Census 1981 v.1 Table 12 Population and Area of each District Electoral Division, Urban District, Rural District and County p.135 Monaghan No.41"

- ↑ "Census 1991 v.1 p.141 Table 13 Population and area of each County, County Borough, Urban District, Rural District and District Electoral Division/Ward Monaghan No.41"

- ↑ "A0106: 1996 Population Density and Area Size by Electoral Division, CensusYear and Statistic"

- ↑ "Census 2006 v.1 p.118 Table 6 Population and area of each Province, County, City, urban area, rural area and Electoral Division, 2002 and 2006 Monaghan No.41"

- ↑ "Census Mapping: Electoral Divisions: Drummully". CSO. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

Sources

- Duffy, Patrick J. (1981). "The Territorial Organisation of Gaelic Landownership and its Transformation in County Monaghan, 1591-1640". Irish Geography. 14: 1–26. doi:10.1080/00750778109478896. ISSN 0075-0778.; reprinted in Fraser, Alistair, ed. (2012). "Chapter 4" (PDF). Anniversary essays : forty years of geography at Maynooth. National University of Ireland, Maynooth. pp. 57–83. ISBN 9780992746605. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Irish Boundary Commission; Hand, Geoffrey J. (1969). Report of the Irish Boundary Commission, 1925. Shannon: Irish University Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-0997-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Leary, Peter (2016). Unapproved Routes: Histories of the Irish Border, 1922–1972. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191084324. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

Further reading

- Durnford, Edward (1990). "Parish of Drummully, County Fermanagh". In Day, Angélique; McWilliams, Patrick (eds.). Parishes of Co. Fermanagh 1, 1834–5 Enniskillen and Upper Lough Erne. Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland. Vol. 4. Institute of Irish Studies. pp. 34–40. ISBN 9780853893592.

External links

- Census 2016: Drummully — Small Area Population Statistics from Central Statistics Office

- Geohive map centred on Drummully – zoomable and with historical layers from Ordnance Survey Ireland