| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dəˈkɑːrbəˌziːn/ |

| Trade names | DTIC-Dome, others |

| Other names | DTIC[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682750 |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Metabolism | Extensive |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (40% as unchanged dacarbazine) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.022.179 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

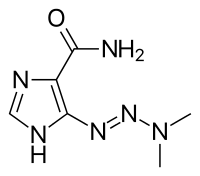

| Formula | C6H10N6O |

| Molar mass | 182.187 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Dacarbazine, also known as imidazole carboxamide and sold under the brand name DTIC-Dome, is a chemotherapy medication used in the treatment of melanoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma.[3] For Hodgkin's lymphoma it is often used together with vinblastine, bleomycin, and doxorubicin.[3] It is given by injection into a vein.[3]

Common side effects include loss of appetite, vomiting, low white blood cell count, and low platelets.[3] Other serious side effects include liver problems and allergic reactions.[3] It is unclear if use in pregnancy is safe for the baby.[3] Dacarbazine is in the alkylating agent and purine analog families of medication.[3]

Dacarbazine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1975.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4]

Medical uses

As of mid-2006, dacarbazine is commonly used as a single agent in the treatment of metastatic melanoma,[5][6] and as part of the ABVD chemotherapy regimen to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma,[7] and in the MAID regimen for sarcoma.[8][9] Dacarbazine was proven to be just as efficacious as procarbazine,[10] another drug with similar chemistry, in the German trial for paediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma, without the teratogenic effects. Thus COPDAC has replaced the former COPP regime in children for TG2 & 3 following OEPA.[11]

Side effects

Like many chemotherapy drugs, dacarbazine may have numerous serious side effects, because it interferes with normal cell growth as well as cancer cell growth. Among the most serious possible side effects are birth defects to children conceived or carried during treatment; sterility, possibly permanent; or immune suppression (reduced ability to fight infection or disease). Dacarbazine is considered to be highly emetogenic,[12] and most patients will be pre-medicated with dexamethasone and antiemetic drugs like 5-HT3 antagonist (e.g., ondansetron) and/or NK1 receptor antagonist (e.g., aprepitant). Other significant side effects include headache, fatigue and occasionally diarrhea.

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare has sent out a black box warning and suggests avoiding dacarbazine due to liver problems.[13]

Mechanism of action

Dacarbazine is activated by liver microsomal enzymes to monomethyl triazeno imidazole carboxamide (MTIC), which is an alkylating compound.[14] It causes methylation, modification and cross linking of DNA, thus inhibiting DNA, RNA and protein synthesis.[15]

Synthesis

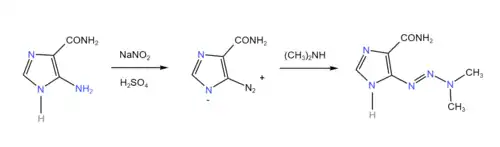

Nitrous acid is added to 5-aminoimidazol-4-carboxamide to make 5-diazoimidazol-4-carboxamide. It reacts with dimethylamine to give dacarbazine.[16]

History

In 1959, dacarbazine was first synthesized at Southern Research in Alabama.[17] The research was funded by a US federal grant. Dacarbazine gained FDA approval in May 1975 as DTIC-Dome. The drug was initially marketed by Bayer.

Society and culture

There are generic versions of dacarbazine available from APP, Bedford, Mayne Pharma (Hospira) and Teva.

References

- ↑ Elks J, Ganellin CR, eds. (1990). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 344–. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2085-3. ISBN 978-1-4757-2087-7.

- ↑ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Dacarbazine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ Serrone L, Zeuli M, Sega FM, Cognetti F (March 2000). "Dacarbazine-based chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma: thirty-year experience overview". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 19 (1): 21–34. PMID 10840932.

- ↑ Bhatia S, Tykodi SS, Thompson JA (May 2009). "Treatment of metastatic melanoma: an overview". Oncology. 23 (6): 488–496. PMC 2737459. PMID 19544689.

- ↑ Rueda Domínguez A, Márquez A, Gumá J, Llanos M, Herrero J, de Las Nieves MA, et al. (December 2004). "Treatment of stage I and II Hodgkin's lymphoma with ABVD chemotherapy: results after 7 years of a prospective study". Annals of Oncology. 15 (12): 1798–1804. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh465. PMID 15550585.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Elias A, Ryan L, Aisner J, Antman KH (April 1990). "Mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, dacarbazine (MAID) regimen for adults with advanced sarcoma". Seminars in Oncology. 17 (2 Suppl 4): 41–49. PMID 2110385.

- ↑ Pearl ML, Inagami M, McCauley DL, Valea FA, Chalas E, Fischer M (2001). "Mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and dacarbazine (MAID) chemotherapy for gynecological sarcomas". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 12 (6): 745–748. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01139.x. PMID 12445253. S2CID 25246937.

- ↑ Jelić S, Babovic N, Kovcin V, Milicevic N, Milanovic N, Popov I, et al. (February 2002). "Comparison of the efficacy of two different dosage dacarbazine-based regimens and two regimens without dacarbazine in metastatic melanoma: a single-centre randomized four-arm study". Melanoma Research. 12 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1097/00008390-200202000-00013. PMID 11828263. S2CID 32031568.

- ↑ Mauz-Körholz C, Hasenclever D, Dörffel W, Ruschke K, Pelz T, Voigt A, et al. (August 2010). "Procarbazine-free OEPA-COPDAC chemotherapy in boys and standard OPPA-COPP in girls have comparable effectiveness in pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma: the GPOH-HD-2002 study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 28 (23): 3680–3686. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.26.9381. PMID 20625128.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Aoki S, Iihara H, Nishigaki M, Imanishi Y, Yamauchi K, Ishihara M, et al. (January 2013). "Difference in the emetic control among highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens: Implementation for appropriate use of aprepitant". Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 1 (1): 41–46. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.15. PMC 3956247. PMID 24649120.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ "Alla aktuella ändringar för Dacarbazine medac Pulver till infusionsvätska, lösning 500 mg, Medac". FASS.se. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ↑ Kewitz S, Stiefel M, Kramm CM, Staege MS (January 2014). "Impact of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation and MGMT expression on dacarbazine resistance of Hodgkin's lymphoma cells". Leukemia Research. 38 (1): 138–143. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2013.11.001. PMID 24284332.

- ↑ "Dacarbazine". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. PMID 31644220.

- ↑ Vardanyan RS, Hruby VJ (2006). "30 - Antineoplastics". Synthesis of Essential Drugs. pp. 389–418. doi:10.1016/B978-044452166-8/50030-3. ISBN 9780444521668.

- ↑ Marchesi F, Turrizani M, Tortorelli G, Avvisati G, Torino F, De Vecchis L (October 2007). "Triazene compounds: Mechanism of action and related DNA repair systems". Pharmacological Research. 56 (4): 275–287. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2007.08.003. PMID 17897837.