| Greater Awyu | |

|---|---|

| Digul River | |

| Geographic distribution | Digul watershed, New Guinea |

| Linguistic classification | Trans–New Guinea |

| Proto-language | Proto-Digul River |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | grea1275 |

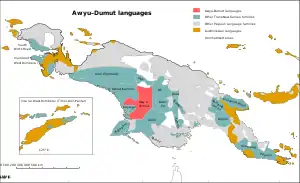

Map: The Awyu–Dumut languages of New Guinea

The Awyu–Dumut languages (other languages not shown)

Other Trans–New Guinea languages

Other Papuan languages

Austronesian languages

Uninhabited | |

The Greater Awyu or Digul River languages, known in earlier classifications with more limited scope as Awyu–Dumut (Awyu–Ndumut), are a family of perhaps a dozen Trans–New Guinea languages spoken in eastern West Papua in the region of the Digul River. Six of the languages are sufficiently attested for a basic description; it is not clear how many of the additional names (in parentheses below) may be separate languages.

History

The Awyu (pronounced like English Ow you) and Awyu–Dumut families were identified by Peter Drabbe in the 1950s.

Voorhoeve included them in his proposed Central and South New Guinea group.[2] As part of Central and South New Guinea, they form part of the original proposal for Trans–New Guinea.[3]

Classification

The classification below is based on Usher[4] and de Vries et al. (2012),[5] who used morphological innovations to determine relatedness, which can be obscured by lexical loanwords.

- Sawi (Sawuy)

- Awyu–Dumut (Central Digul River)

- Awyu languages: Aghu (Jair), Shiaxa (Jenimu, Edera), Pisa (Asuwe)

- Ndeiram–Ndumut

- Dumut (Wambon) branch: Mandobo (Kaeti, Dumut), Wambon

- Ndeiram River: Kombai–Wanggom

- North Digul River

- Awbono-Bayono

- Becking–Dawi

- Dawi River: Komyandaret, Tsaukambo

- Becking River: Korowai

Sawi is classified on pronominal data, as the morphological data used for the rest of the family is not available.

Pawley and Hammarström (2018) exclude Awbono-Bayono, treating it as a separate family.[6]

Various other languages can be found in the literature. Airo-Sumaxage (Airo-Sumaghage)[7] is listed in Wurm, Foley, etc., but not in the University of Amsterdam survey and has been dropped by Ethnologue. Ethnologue lists a 'Central Awyu', but this is not attested as a distinct language (U. Amsterdam). In general, the names in Ethnologue are quite confused, and older editions speak of names from Wurm (1982), such as Mapi, Kia, Upper Digul, Upper Kaeme, which are names of language surveys along the rivers of those names, and may actually refer to Ok languages rather than to Awyu.

van den Heuvel & Fedden (2014) argue that Greater Awyu and Greater Ok are not genetically related, but that their similarities are due to intensive contact.[8]

Reconstruction

| Proto-Digul River | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Greater Awyu languages |

Reconstructed ancestors | |

Phonemes

Usher (2020) reconstructs "perhaps" 15 consonants and 8 vowels, as follows:[9]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | |||||

| Nasal | *m | *n | ||||

| Plosive | plain | *p | *t | *k | *kʷ | |

| prenasalized | *ᵐb | *ⁿd | *ⁿdz | *ᵑɡ | *ᵑɡʷ | |

| Fricative | *s | |||||

| Semivowel | *w | *j | ||||

| Rhotic | *ɾ | |||||

Pronouns

Usher (2020) reconstructs the pronouns as:[9]

sg pl 1 *nup 2 *ngup *ngip 3

Ross (2005) reconstructs the pronouns of the Awyu–Dumut branch as follows:

sg pl 1 *nu-p *na-gu-p 2 *gu-p *ga-gu-p 3 *e-p, *[n]ege-p, *yu-p *ya-gu-p

The suffix *-p and the change of the final TNG *a vowel to *u do not appear in the possessive pronouns: *na, *ga, *ya/wa, *na-ga, *ga-ga, *ya-ga.

Basic vocabulary

Healey (1970) and Voorhoeve (2000)

The following selected reconstructions of Proto-Awyu-Dumut, Proto-Awyu, and Proto-Dumut by Voorhoeve are from Healey (1970)[10] and Voorhoeve (2000),[11] as cited in the Trans-New Guinea database:[12]

gloss Proto-Awyu-Dumut Proto-Awyu Proto-Dumut head *kɑibɑn; *xaiban *xaiban; *xɑibɑn *kɑbiɑn; *kebian hair *möxö; *muk; *ron *mox; *mux; *ron *mökö-ron; *muk; *ron ear *turun *turun *turutop; *turu=top eye *kerop *kero *kerop nose *togut *togut tongue *fɔgat; *fɔgɛt; *pogɑt *fagɛ; *fɑge *ogat; *pɑgɑt louse *gut *go; *gu; *ɑgu *gut dog *angay; *ɑgɑi; *set *sɛ; *(y)ange; *(y)angi; *yɑgi *agay; *ɑgɑi; *tit pig *wi *wi *uy bird *yet *yi *yet egg *wɑidin *mugo *wɑdin blood *gom *gon *gom bone *bogi *mit skin *kɑt; *xa(t) *xɑ; *xa *kotay; *kɑtɑy breast *ɑm; *om *om; **om *om; *ɔm tree *yin *yin *in woman *ran; *rɑn *ran; *rɑn *ran; *rɑn sky **xuit *xuito *kut sun *seyɑt *sɑt moon *wɑkot *wɑkot water *ox *ɔx; *óxo *ok fire *yin *yin stone *irop *ero; *iro *irop name *füp; *pip *fi *fip; *üp eat *ɑde; *en; *ɛn- *ɑde-; *en; *ɛn- *ɑde; *en; *en- two *rumo; *rumon *okorumon; **ok=rumɔ(n) *irumon; *rumo

Usher (2020)

Some lexical reconstructions of Proto-Digul River and lower-level reconstructions by Usher (2020) are:[9]

gloss Proto-Digul River Sawuy Proto-North Digul Proto-Central Digul head *kamb[e̝]jan *kabe̝jan *kambijan leaf/hair *mo̝k moːx *mo̝k *mo̝k tongue *te̝p seːp ~ seɸ *te̝p skin/bark *kat *kat breast aːm *am *ɒm dog *tit siːr *tit *tit bird *ndzeːt eːr *dze̝t *je̝t egg *mug[o/ɔ] mugo *mugɔ sun/day *[a]tap ataːp moon *wakɔɾ oxaːr *wakɔɾ *wakɔɾ water aːx *[a/ɔ]k *ɔk

Evolution

Greater Awyu reflexes of proto-Trans-New Guinea (pTNG) etyma are:[6]

- maŋgot ‘teeth, mouth’ < *maŋgat[a]

- (Wambon S.) kodok ‘leg’ < *k(a,o)ndok[V]

- mok ‘seed’ < *maŋgV

- kotay ‘bark, skin’ < *(ŋg,k)a(nd,t)apu

- kondok ‘bone’ < *kwanjaC

- kim- ‘die’ < *kumV-

- kinum- ‘sleep’ < *kin(i,u)-

- ok ‘water, river’ < *okV

- enop ‘fire’ < *kendop

- (ko)sep ‘ashes’ < *(kambu-)sumbu

- (Wambon N.) kumut ‘thunder’ < *kumut or *tumuk

- ururuk ko- ‘to fly’ < *pululu

- am ‘breast’ < *amu

- magot ‘mouth’ < *maŋgat[a]

- koman ‘neck’ < *k(o,u)ma(n,ŋ)[V]

- (a)moka ‘cheek’ < *mVkVm ‘cheek, jaw’

- kere(top) ‘ear’ < *kand(e,i)k(V]

- betit ‘fingernail’ < *mb(i,u)t(i,u)C

- kodok ‘foot, leg’ < *k(a,o)ndok[V]

- otae ‘bark, skin’ < *(ŋg,k)a(nd,t)apu

- kiow ‘wind’ < *kumbutu

- komöt ‘thunder’ < *kumut

- üp ‘name’ < *imbi

- kinum- ‘sleep’ < *kin(i,u)-

- (ko)tep ‘ashes’ < *(kambu-)sumbu

- ok ‘water, river’ < *okV

- apap ‘butterfly’ < *apa(pa)ta

- mugo ‘egg’ < *maŋgV, kiri

- mogo ‘eye’ < *kiti-maŋgV

- kifi ‘wind’ < *kumbutu

- ise ‘mosquito’ < *kasin

- apero ‘butterfly’ < *apa(pa)ta

- kunu (ri-) ‘sleep’ < *kin(i,u)-

- kekuŋ- ‘carry on the shoulder’ < *kak(i,u)-

- fi ‘name’ < *imbi

- apa ‘butterfly’ < *apa([pa]pata

- boro ‘to fly’ < *pululu

References

- ↑ New Guinea World, Digul River – Ok

- ↑ Voorhoeve, C.L. 1968. “The Central and South New Guinea Phylum: a report on the language situation in south New Guinea. Pacific Linguistics, Series A, No. 16: 1-17. Canberra: Australian National University.

- ↑ McElhanon, Kenneth A.and C.L. Voorhoeve. 1970. The Trans-New Guinea phylum: explorations in deep-level genetic relationships. Pacific Linguistics, Series B, No. 16. Canberra: Australian National University.

- ↑ New Guinea World - Digul River

- ↑ Lourens de Vries, Ruth Wester, & Wilco van den Heuvel. 2012. "The Greater Awyu language family of West Papua", pp. 269–312 of Hammarström & van den Heuvel (eds.), History, Contact and Classification of Papuan Languages. (Language and Linguistics in Melanesia Special Issue). Port Moresby: Linguistic Society of Papua New Guinea.

- 1 2 Pawley, Andrew; Hammarström, Harald (2018). "The Trans New Guinea family". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 21–196. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- ↑ Multitree qgz

- ↑ van den Heuvel, W. & Fedden, S. (2014). Greater Awyu and Greater Ok: Inheritance or Contact? Oceanic Linguistics 53(1), 1-36. University of Hawai'i Press.

- 1 2 3 New Guinea World

- ↑ Healey, A. 1970. Proto-Awyu-Dumut Phonology. In Wurm, S.A. and Laycock, D. C. (eds). Pacific Linguistic Studies in honour of Arthur Capell. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ Voorhoeve, C. L. 2000. Proto Awyu-Dumut phonology II. In A. Pawley, M. Ross, & D. Tryon (Eds.), The Boy from Bundaberg: studies in Melanesian linguistics in honour of Tom Dutton (pp. 361–381). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ Greenhill, Simon (2016). "TransNewGuinea.org - database of the languages of New Guinea". Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Ross, Malcolm (2005). "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 15–66. ISBN 0858835622. OCLC 67292782.

Further reading

- Proto-Awyu-Dumut. TransNewGuinea.org. From (1) Voorhoeve, C. L. 2000. Proto Awyu-Dumut phonology II. In A. Pawley, M. Ross, & D. Tryon (Eds.), The Boy from Bundaberg: studies in Melanesian linguistics in honour of Tom Dutton (pp. 361–381). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ; (2) Healey, A. 1970. Proto-Awyu-Dumut Phonology. In Wurm, S.A. and Laycock, D. C. (eds). Pacific Linguistic Studies in honour of Arthur Capell. Pacific Linguistics: Canberra.

- Proto-Awyu. TransNewGuinea.org. From (1) Voorhoeve, C. L. 2000. Proto Awyu-Dumut phonology II. In A. Pawley, M. Ross, & D. Tryon (Eds.), The Boy from Bundaberg: studies in Melanesian linguistics in honour of Tom Dutton (pp. 361–381). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ; (2) Healey, A. 1970. Proto-Awyu-Dumut Phonology. In Wurm, S.A. and Laycock, D. C. (eds). Pacific Linguistic Studies in honour of Arthur Capell. Pacific Linguistics: Canberra.

- Proto-Dumut. TransNewGuinea.org. From (1) Voorhoeve, C. L. 2000. Proto Awyu-Dumut phonology II. In A. Pawley, M. Ross, & D. Tryon (Eds.), The Boy from Bundaberg: studies in Melanesian linguistics in honour of Tom Dutton (pp. 361–381). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ; (2) Healey, A. 1970. Proto-Awyu-Dumut Phonology. In Wurm, S.A. and Laycock, D. C. (eds). Pacific Linguistic Studies in honour of Arthur Capell. Pacific Linguistics: Canberra.

External links

- The Awyu–Ndumut languages in their linguistic and cultural context (University of Amsterdam)

- Timothy Usher, New Guinea World, Proto–Digul River – Ok

- (ibid.) Proto–Digul River (see also reconstructions of North and Central Digul River)

- (ibid.) Digul River. New Guinea World.