| Torricelli | |

|---|---|

| Torricelli Range – Sepik Coast | |

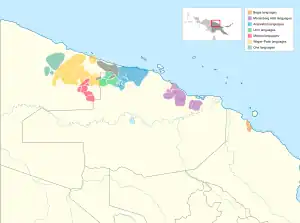

| Geographic distribution | Torricelli Range and coast, northern Papua New Guinea (East Sepik, Sandaun, and Madang provinces) |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | nucl1708 (Nuclear Torricelli) |

The Torricelli languages as classified by Foley (2018) | |

The Torricelli languages are a family of about fifty languages of the northern Papua New Guinea coast, spoken by about 80,000 people. They are named after the Torricelli Mountains. The most populous and best known Torricelli language is Arapesh, with about 30,000 speakers.

They are not clearly related to other Papuan language families; however, attempts have been made to establish external links.[1] The most promising external relationship for the Torricelli family is the Sepik languages. (In reconstructions of both families, the pronouns have a plural suffix *-m and a dual suffix *-p.)

C.L. Voorhoeve (1987) has proposed that they are related to the North Halmahera languages and most of the languages of the Bird’s Head Peninsula, thus forming the easternmost extension of the postulated West Papuan family.[2]

History

The Torricelli languages occupy three geographically separated areas, evidently separated by later migrations of Sepik-language speakers several centuries ago. Foley considers the Torricelli languages to be autochthonous to the Torricelli Mountains and nearby surrounding areas, having been resident in the region for at least several millennia. The current distribution of Lower Sepik-Ramu and Sepik (especially Ndu) reflects later migrations from the south and the east.[3] Foley notes that the Lower Sepik and Ndu groups have lower internal diversity comparable to that of the Germanic and Romance languages, while internal diversity within the Torricelli family is considerably higher.

Typological overview

Syntax

The Torricelli languages are unusual among Papuan languages in having a basic clause order of SVO (subject–verb–object). (In contrast, most Papuan languages have SOV order.) It was previously believed that the Torricelli word order was a result of contact with Austronesian languages, but Donohue (2005) believes it is more likely that SVO order was present in the Torricelli proto-language.[4]

Torricelli languages display many typological features that are direct opposites of features typical in the much more widespread Trans-New Guinea languages.[5]

- Torricelli: prepositions, SVO, left-branching

- Trans-New Guinea: postpositions, SOV, right-branching

However, Bogia and Marienberg languages have SOV word order and postpositions, likely as a result of convergence with Lower Sepik-Ramu and Sepik languages, which are predominantly SOV.[5]

Torricelli languages also lack clause chaining constructions, and therefore have no true conjunctions or clause-linking affixes.[5] Clauses are often simply juxtaposed.

Nouns

In Torricelli and Lower Sepik-Ramu languages, phonological properties of nouns can even determine gender.[5]

Like in the Yuat and Lower Sepik-Ramu languages, nouns in Torricelli languages are inflected for number, which is a typological feature not generally found in the Trans–New Guinea, Sepik, Lakes Plain, West Papuan, Alor–Pantar, and Tor–Kwerba language families.[6]

Classification

Wilhelm Schmidt linked the Wapei and Monumbo branches, and the coastal western and eastern extremes of the family, in 1905. The family was more fully established by David Laycock in 1965. Most recently, Ross broke up Laycock and Z’graggen's (1975) Kombio branch, placing the Kombio language in the Palei branch and leaving Wom as on its own, with the other languages (Eitiep, Torricelli (Lou), Yambes, Aruek) unclassified due to lack of data. Usher tentatively separates Monumbo, Marienberg, and the Taiap (Gapun) language from the rest of the family in a 'Sepik Coast' branch.[7]

- Torricelli

- Sepik Coast

- Torricelli Range

- Wom

- Arapesh branch (see)

- Maimai branch: Nambi (Nabi), Wiaki (Minidien), Beli, Laeko, Maimai proper (Siliput, Yahang–Heyo)

- West Wapei branch: Seti, Seta, One (a dialect cluster)

- Wapei branch: Gnau, Yis, Yau, Olo, Elkei, Au, Yil, Ningil, Dia–Sinagen (both Alu, Galu), Yapunda, Valman

- Palei branch: Urim, Urat, Kombio, Agi, Aruop, Wanap (Kayik), Amol (Alatil, Aru), Aiku (Ambrak, Yangum)

Foley (2018)

Foley (2018) provides the following classification.[3]

Foley rejects Laycock's (1975) Kombio-Arapeshan grouping, instead splitting up into the Arapesh and Urim groups.

Glottolog v4.8

Glottolog v4.8 presents the following classification for the "Nuclear Torricelli" languages:[8]

- Nuclear Torricelli

- Beli (Papua New Guinea)

- Kombio–Arapesh–Urat (10 languages)

- Laeko–Libuat

- Marienberg (7 languages)

- Nuclear Maimai (3 languages)

- Gnau (unclassified)

- Urim

- Wapei–Palei (22 languages)

- West Wapei (8 languages)

- Wom (Papua New Guinea)

In addition, Hammarström et al. do not accept the placement of the Bogia languages within Torricelli, stating that "no evidence [for this] was ever presented".[9]

Pronouns

The pronouns Ross (2005) reconstructs for proto-Torricelli are

singular proto-Torricelli dual proto-Torricelli plural proto-Torricelli I *ki we two *ku-p we *ku-m, *əpə thou *yi, *ti you two *ki-p you *ki-m, *ipa he *ətə-n, *ni they two (M) *ma-k they (M) *ətə-m, *ma, *apa- she *ətə-k, *ku they two (F) *kwa-k they (F) *ətə-l

Foley (2018) reconstructs the independent personal pronouns *ki ‘I’ and *(y)i ‘thou’, and *(y)ip ‘you (pl)’. Foley considers the second-person pronouns to be strong diagnostics for determining membership in the Torricelli family.

Foley (2018) reconstructs the following subject agreement prefixes for proto-Torricelli.[3]

sg pl 1 *k- 2 3m *n- *m- 3f *w-

Lexical comparison

The lexical data below is from the Trans-New Guinea database.[10]

| branch | language | head | hair | ear | eye | nose | tooth | tongue | leg | blood | bone | skin | breast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | One, Inebu | selə | tipi | namla | suwla | nala | alfoi | teu | fampwi | amla | plapi | nimla | |

| West Wapei | Seta | sela; sila | sila batalayo | tɩbɩli; təpəli | namana; naməna | sulu; sülü | nɛla; nelə | ngctela; ŋkotelə | teu | soli | kamóya | tapeo; tapio | mommo; momo |

| Wapei | Ningil | waʔal | məkər | namək | nəfənək | na: | wa:r | yau | ni:kri | ləmeʔi | fa:wal | ma:ʔ | |

| Palei | Aruop | wantu | yaŋkole | yolta | mup | na | aləta | ala | səna | pəniŋki | wiye | yimá | |

| Maimai | Heyo | utüwe | rakun | napelkə | luweka | parkita | elktife | itikya | wiyefa | yefa | halipa | maka | |

| Maimai | Beli | ŋətə | satoʔ | suwopən | niŋo | life | papaŋ | kuijwẽ | loknwẽ | noʔoŋ | mapi | ||

| Urim | Urim | ləŋkəp | nurkul | i:kŋ | ləmp | e:k | milip | ne:p | waləmpop | təpmuŋkut | palək | ma: | |

| Urat | Urat | ntoh | kwin | ampep | muhroŋ | asep | nihip | wim | lupuŋ | yahreik | ampreip | ||

| Kombio | Torricelli | emen | wolep | yempit | wujipen | nal | yaŋklou | araiʔ | yalkup | ləp | alou | yimep | |

| Arapesh | Abu' Arapesh | bʌrʌkʰa | bʌrʌkʰa | ɛligʌ | ŋʌim | mutu | nʌluh | ʌhʌkʌ | burʔah | usibɛl | pisitʌnʌgel | beni'koh | numʌb |

| branch | language | louse | dog | pig | bird | egg | tree | sun | moon | water | fire | stone | path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | One, Inebu | munola | pa:la | nawra | amu | silo | ayre | anini | fa:la | ni:pi | ta:ma | ||

| West Wapei | Seta | təmofəl | balə; pa:lə | pəsiapa; pɩsapə | a:mo; gambu | si | kebɩli; kepli | anine; funmo | mi | sakul; sakulu | kuləbol; tumala | plɛn | |

| Wapei | Ningil | nəmaŋkar | faré: | aprei | yu:lək | lu: | wufliyəx | onyil | ni: | walk | xəroi | ||

| Palei | Aruop | yimunə | yimpa | ali | yoltə | nəmpə | wa | anyə | suku | yimpu | atauka | ||

| Maimai | Heyo | hipəp | mpat | walfisa | laʔwo | lowə | fala | onifəʔ | hipelə | yafa | paleka | ||

| Maimai | Beli | pato | walfun | lawiyen | lowo | watli | waluko | ite | safi | kalkopo | |||

| Urim | Urim | nəmin | nəmpa | wel | haləmpar | yo: | takəni | kanyil | huw | wa:kŋ | weit | ||

| Urat | Urat | ompik | pwat | antet | lou | nai | wantihi | pənip | nih | yah | |||

| Kombio | Torricelli | numuk | yimpeu | elip | yimpwonən | lu | awən | iyén | wop | yotou | əntoʔ | ||

| Arapesh | Abu' Arapesh | numunʌl | nubʌt | bul | ʌlimil | ʌlhuʌb | lʌ·wʌk | uʔwʌh | 'ʌ'un | ʌbʌl | unih | utʌm | iʌh |

| branch | language | man | woman | name | eat | one | two |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | One, Inebu | mana | pi:ni | plale | |||

| West Wapei | Seta | manə; oma | bɩni; pin | wune woyuye | pəla | ||

| Wapei | Ningil | masin | naʔ aipi | wilal | |||

| Palei | Aruop | makenti | simi | piya | |||

| Maimai | Heyo | mohon | nuweteʔ | oloʔw | |||

| Maimai | Beli | masən | sakwoto | wosoŋ | |||

| Urim | Urim | kəmel | ki:n | we:k | |||

| Urat | Urat | mik | tuwei | hoi | |||

| Kombio | Torricelli | eiŋ | injik | wiyeu | |||

| Arapesh | Abu' Arapesh | ʌʔlemʌn | numʌto | ɛigil | 'nʌsʌh | etin | biəs |

Cognate sets

A cognate set for 'louse' in Torricelli languages as compiled by Dryer (2022):[11]

Language (group) louse Marienberg nəmi, ɲumo, ɲɛm, ɲimi Central Wapei nəmk, nəmeiləm, nimim East Wapei nəmaŋgar, namkar Wanap ɲiməl Urat ŋumbu Kombio ɲumək, niumukn, ɲumukŋun Arapeshan numunəl, nəmaŋgof Wom numulɛ West Palei ɲmulol Urim nmin Maimai yomata East Palei ymunə, ymul West Wapei muni, moni, munola

See also

References

- ↑ Wurm, Stephen A. (2007). "Australasia and the Pacific". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Abingdon–New York: Routledge. pp. 425–577. doi:10.4324/9780203645659. ISBN 9780203645659.

- ↑ Voorhoeve, C.L. (1987). "Worming one's way through New Guinea : The chase of the peripatetic pronouns". In Laycock, Donald L.; Winter, Werner (eds.). A world of language: papers presented to Professor S.A. Wurm on his 65th birthday. Pacific Linguistics C-100. Canberra: Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. pp. 709–727. ISBN 0-85883-357-3.

- 1 2 3 Foley, William A. (2018). "The Languages of the Sepik-Ramu Basin and Environs". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 197–432. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- ↑ Donohue 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Foley, Bill. 2005. Papuan languages, as written for the International Encyclopedia of Linguistics 2003.

- ↑ Foley, William A. (2018). "The morphosyntactic typology of Papuan languages". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 895–938. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- ↑ "Sepik Coast - newguineaworld". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2023-07-10). "Glottolog 4.8 - Nuclear Torricelli". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7398962. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2023-07-10). "Glottolog 4.8 - Bogia". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7398962. Archived from the original on 2023-10-18. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Greenhill, Simon (2016). "TransNewGuinea.org - database of the languages of New Guinea". Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- ↑ Dryer, Matthew S. (2022). Trans-New Guinea IV.2: Evaluating Membership in Trans-New Guinea.

Bibliography

- Donohue, Mark (2005). "Word order in New Guinea: dispelling a myth". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (2): 527–536. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0033. S2CID 38009656.

- Laycock, Donald C. 1968. Languages of the Lumi Subdistrict (West Sepik District), New Guinea. Oceanic Linguistics, 7 (1): 36-66.

- Ross, Malcolm (2005), "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages", in Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.), Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, pp. 15–66