| Durolle | |

|---|---|

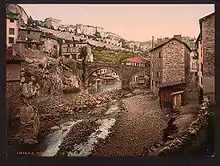

The Durolle near the May factory in Thiers | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Massif Central |

| Mouth | Dore |

• coordinates | 45°50′26″N 3°29′57″E / 45.84042°N 3.49909°E |

| Length | 32.1 km (19.9 mi) |

| Basin size | 172 km2 (66 sq mi) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Dore→ Allier→ Loire→ Atlantic Ocean |

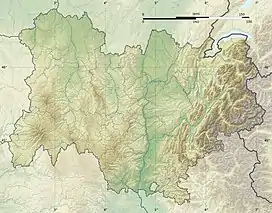

The Durolle (formerly Dorole) is a 32-kilometer-long French river in the departments of Loire and Puy-de-Dôme, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region. A right-bank tributary of the Dore, which it joins downstream of Thiers, it is a sub-tributary of the Loire via the Allier.[1]

The river rises in the Forez mountains, where rainfall is high throughout the year. After flowing past the town of Noirétable, the Durolle plunges into deep canyons (until it exits the Vallée des Rouets and the Vallée des Usines) renowned for their rich natural and industrial heritage. Known since the Middle Ages for its paper mills, the river owes its fame to its motive power, which enabled cutlery factories to sharpen knives. Today, the river's industrial past is used as a tourist attraction.

Toponymy

The river's name is thought to derive in part from the (presumed) Celtic root dour or dor, meaning "river" in French.[2] The Dore (the river into which the Durolle flows) also takes its name from these "Celtic" roots. However, the authoritative Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de rivières et de montagnes de France by Albert Dauzat, Gaston Deslandes and Charles Rostaing (Paris, Klincksieck, 1978) explains Dore (and Durolle) by a pre-Celtic radical "found in the Douro of Spain, the two Dora of Piedmont, etc." (article DORE). Moreover, Xavier Delamarre's Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (2nd edition, Paris, Errance, 2003) does not indicate any Celtic term dor or dour meaning river.

The Durolle, formerly called "Dorole", means "little Dore".[1] Its nickname, the Goutte noire (black drop), refers to its color in the 19th century when spinning wheels used the river's water, and is borne by a village crossed by the river in the commune of Chabreloche.[3] The river's name is also used by two communes in the region: Celles-sur-Durolle and Saint-Rémy-sur-Durolle,[3] and a place called Durolle in the commune of Noirétable.

It is called Duròla in Occitan, the regional language of Auvergne.[4]

Geography

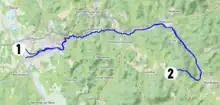

River course

Just over 32 km long, the Durolle begins its course at an altitude of around 815 m southeast of the Puy de la Chèvre in the commune of Noirétable in the Loire department.[1][5] It skirts the town of Noirétable without crossing it, then passes through a number of villages overlooking it, before passing through towns such as Chabreloche and La Monnerie-le-Montel, and finally arriving at the largest town it flows through, Thiers, a town with a strong historical link to it, where it also flows into the Dore.[1]

Upstream, the river follows part of the Forez mountains where it rises, until it enters the commune of La Monnerie-le-Montel, where it divides the Forez foothills.[5] From here, until it leaves the Vallée des Usines in the Moutier district of Thiers, the river flows through a deep valley with small banks, where the cliffs and rocks of the Margerides plunge.[6] The rugged, largely wooded terrain gives the river a sinuous course that follows the steep curves of the mountain.[7] From the point where it passes near Moutier Abbey, the Durolle becomes calmer and the very flat terrain divides its bed into two branches, before these join the Dore at different geographical positions.[7]

Hydrology

The drainage basin of the river Durolle measures 172 km2.[8] Its modulus, measured near the Saint-Roch bridge in Thiers, halfway between the source and the mouth, is 3 m3/s.[1] Flow varies significantly throughout the year, and from one year to the next.[3] In dry summer months, the river's flow may drop to 0.05 m3/s; but in winter or autumn, it can rise rapidly to 82 m3/s, as was the case during the flood of March 1988.[9][10] The river's tributaries are generally small streams with low flows.[9] The main ones are, from upstream to downstream, the Membrun stream, the Pigerolles stream, the Prade stream, the Aubusson stream, the Jalonne, the Semaine, the Dauge, the Martignat, the Bouchet, the Ris and the Boucheries stream.[1][3][9]

The Membrun dam, located in the commune of Thiers, lies on the course of the Durolle.[9][10] It was impounded on 22 May 1985 to regulate the river's flow, particularly during periods of drought. Since the late 1980s, the dam has become a popular destination for hikers and walkers.

Communes and cantons crossed

In both the Loire and Puy-de-Dôme departments, the Durolle flows through the following seven communes,[1] from upstream to downstream: Noirétable (source), Cervières, Les Salles, Chabreloche, Celles-sur-Durolle, La Monnerie-le-Montel, Thiers (confluence).[1]

In terms of cantons, the Durolle rises in the canton of Boën-sur-Lignon, and flows into the canton of Thiers, all in the arrondissements of Montbrison and Thiers.[1]

Toponyms

The Durolle has given its hydronym to the two communes of Celles-sur-Durolle and Saint-Rémy-sur-Durolle, the latter crossed by a tributary of the Durolle, the Ris.

Drainage basin

The Durolle crosses the three catchment areas K295, K296, K297, with a total surface area of 1,456 km.[1] The drainage basin is made up of 58.37% "forests and semi-natural environments", 39.63% "agricultural land" and 2.01% "artificial land".[1]

Geology

The geological context of the Durolle has resulted in a river divided into two distinct geological territories, separated by a boundary represented by the Moutier abbey, which lies in the middle of the river.[11] The geological history of the Thiernoise region is characterized by the presence of a major north-south trending fault affecting the regional geological basement: it delimits this basement into distinct blocks while serving as a guide to the tectonic collapse of the western block, while the eastern block remains more or less in place.[11] To the west, the collapse of the block allows sedimentary rocks to fill in: this is the Limagne basin, over which the Durolle flows slowly. To the east, the part of the basement that has not collapsed corresponds to the Forez mountains and its foothills, made up of magmatic rocks over which the river flows torrentially.[11]

The oldest outcrops in the upper part of the river are Paleozoic in age, consisting of various granites sometimes overlain by grus and scree. In the lower reaches, the sedimentary fill is Cenozoic in age; this terrain is not visible, as it is covered by a thick mantle of recent alluvium, sandy and clayey, layered in terraces.[12]

Fauna and flora

Numerous plant species have been recorded on the banks of the Durolle.[13] Among them, the most common plant species are ferns (with two species: eagle fern and male fern), plant mosses, European ivy, rubus fruticosus, nettles, clematis, ash and euphorbia. Several tree species are also present in the Durolle's major and minor stream bed, including oaks, broom and fir.[13]

The Durolle canyons are home to several species of fauna, divided into several categories.[13] Mammals include otters and European polecat, while birds range from peregrine falcons and yellowhammers to coal tit and western Bonelli's warbler.[13] The trout is another fish species that lives in rivers with abundant currents and cool temperatures, such as the Durolle, where this species is widespread.[14][15]

Tributaries

The Durolle has thirteen referenced tributary sections,[1] including:

- la Jalonne (rd), 7.8 km in the commune of Celles-sur-Durolle alone;

- the Semaine or Fonghas stream (rg), 11.5 km on the three communes of Viscomtat, Noirétable and Celles-sur-Durolle, with four tributaries including one branch;

- the Dauge (rg), 3.8 km on the commune of Celles-sur-Durolle alone;

- the Martignat or Ruisseau de l'Allemand, 3.8 km in the commune of Celles-sur-Durolle alone;

- le Bouchet (rg), 3.6 km in the communes of Celles-sur-Durolle and La Monnerie-le-Montel;

- les Ris (rd), 5.2 km on the three communes of Palladuc, Saint-Rémy-sur-Durolle and La Monnerie-le-Montel.

So its Strahler number is three.

History

A long history of human occupation

Gateway to the Rhone corridor

An early Gallic settlement (the future town of Thiers) was established at the mouth of the Durolle Gorge, not far from the site of the later Moutier Abbey.[16] The name "Thigernum" used by Grégoire de Tours has a Celtic ring to it, reminding us that this topographical appellation dates from before the Gallic War. The first town seems to have been a road station crossed by a Roman road (the via Agrippa) linking the town of Mediolanum Santonum to Lugdunum via Augustonemetum (Saintes to Lyon via Clermont-Ferrand). But this route was not the only one to link the Allier and Loire valleys. Indeed, although the tortuous Durolle valley was difficult to navigate in its lower reaches, footpaths and bridleways followed the riverbed. The fortified town of Thiers fulfilled this role to the full, commanding the entrance to the Durolle Gorge.

Spinning wheels and factories

Middle Ages

The Durolle's hydraulic power was used in Thiers from the Middle Ages onwards to power flour mills, tanners' fulling machines, papermakers' mallets and, with the development of cutlery, smelters' hammers and grinders.[17][18] In the 17th century, objects produced in the Durolle Gorge were exported to Spain, Italy, Germany, Turkey and the Indies.[19]

Industrial revolution

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the cutlery industry was the only one to survive, thanks to the introduction of machines that heralded the advent of large-scale industry.[20] At that time, the cutlery industry was particularly organized. The manpower needed to make a knife was scattered across the Thiers region; there was an extreme division of labor, with workers specializing in a trade, handed down from father to son, in which they acquired great skill.[19] The steel bars received by the companies are first entrusted to the "martinaires", who thin them (so that they can be sharpened) using hammers powered by the river's hydraulic force. The blacksmiths then receive these bars, with which they forge the knife parts. These pieces are then sent to fileers, drillers, grinders and polishers, who sharpen and polish the blades on grindstones driven by the Durolle.[19] The manufacturer does the tempering himself, then, after the sealer has delivered the handles,[21] all the parts are finally handed over to the assemblers, who live in the suburbs of Thiers.[19] The organization of production is thus characterized by the widespread distribution of workplaces in the Thiers region, and more particularly in the Durolle canyons.[19]

At the end of the 19th century, foreign competition prompted Thiers industries to modernize. This modernization involved electrification. A new type of factory was created, integrating all cutlery operations.[19] Paper mills that refused to use these modern production techniques were forced to close; by 1860, there were only around twenty of them left.[22]

The early 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were a growing number of problems concerning the waters of the Durolle.[19][23] Firstly, the river's summer flow remained very low and irregular, leading to periods of unemployment. The factories that use the river's motive power can't operate without a sufficient flow of water.[19] In winter, the phenomenon is reversed: the Durolle becomes a torrent in flood with considerable force. The towns in the Durolle canyons are among the most vulnerable to flooding in the Puy-de-Dôme département.[23]

So as not to be dependent on the whims of the Durolle, the factories began using electric power in 1903. In 1920, the Durolle provided an average of 1,000 horsepower per day, compared with 1,500 horsepower for electric power.[19]

Sailing boats and descending logs

In the Middle Ages, the Durolle served as a communication route for Thiers craftsmen.[24] Products made in the town were often exported out of town, even to Asia via the Durolle and Dore rivers, and on to the Atlantic Ocean via the Loire and Alliera rivers. Ships navigating the shallow waters of the Durolle are often flat-bottomed barques. Navigation starts from the ship's bridge, which marks the last lock in the Durolle. In the 17th century, the royal navy called on Thiers merchants to bring in timber from the region to build the three-masted ships (depicted on the Thiers coat of arms) commissioned by Louis XIV. The logs were cut and thrown into the Durolle river, where they followed the current and waterfalls before arriving in the lower town of Thiers, where they were recovered for use in Paris.[22][24]

Rice cultivation

In 1741, the waters of the Durolle were used to plant rice fields in the lower town of Thiers, as rice was seen at the time as a possible solution to the famine and food shortages that afflicted Europe.[22] But the rice-growing technique was not "followed to the letter", and a few days after this new foodstuff was marketed in the region, an epidemic broke out and became known as the "rice plague", claiming the lives of over 2,500 Thiers residents.[25]

Development of the riverbed for industrial purposes

Locks

To make the best possible use of the Durolle's motive power to turn the various machines used to produce knives, numerous locks were built along the riverbed.[26] They serve to hold back the water to increase the river's depth and divert part of its bed with another branch, which then drives one or more paddlewheels in a waterfall context. In the commune of Thiers, between the Moutier abbey and the Seychalles bridge, 15 locks have been inventoried to supply factories.

Ramps and dikes

In the Middle Ages, fish was an important part of the diet.[26] Religious people ate it during fasting periods, and in abundance during Lent and Advent. To meet their needs, religious communities settled near waterways. While the present-day buildings of Moutier Abbey were being built in the 11th century, the construction of water-powered mills and dams to feed them, for example to grind wheat or fish in the river's reservoirs, was already underway.[26] The establishment of mills on rivers was authorized by the king in non-navigable areas, such as the stretch of the Durolle river between the ship's bridge and Noirétable. In this section, the mills are supplied with water by a dike or a pélière damming the entire river.[26]

Heritage

Spinning wheels and mills

The Durolle valley's industrial history, which led people to build buildings on the river banks, has left behind numerous spinning wheels, water mills and cutlery factories.[27] Today, these buildings are considered a precious industrial heritage. A number of old spinning wheels are located in the upper reaches of the river (such as the Boulary spinning wheel in La Monnerie or the Lyonnais spinning wheel in Thiers), as far as the area around Le Bout du Monde in Thiers, where the industrial landscape is changing dramatically. Large factories built on former mills, such as the Pont de Seychalles factory or the Mondière forges, are taking the place of the spinning wheels.

Churches and abbeys

Many churches and chapels are built on promontories overlooking the Durolle valley, while others are built directly beside the river. As a general rule, each village has its own place of worship. Firstly, the church of Saint-Antoine de Padoue in the commune of La Monnerie-le Montel towers above the roofs of the village center, its high steeple visible from the riverbed.[28] Then there's the Saint-Roch chapel, built on the puy Seigneuret overlooking a meander in the Durolle at the level of the Saint-Roch bridge. The church of Saint-Genès, located in the heart of the medieval town of Thiers, is only slightly visible from the Durolle valley, but the church of Saint-Jean du Passet, located at the end of the rocky spur on which the old town of Thiers is built, is highly visible from the Creux de l'Enfer due to its overhanging position. A little further down, the Moutier abbey and Saint-Symphorien church, whose buildings date back to the 11th century, are strongly linked to the river by their history.

Bridges

Numerous bridges have been built across the Durolle since the Middle Ages. The oldest, the Pont Vielh, spans the river with its single pier, while the busiest, the Pont de Bridgnorth, owes its name to the town of Bridgnorth in the UK, which is twinned with Thiers.[29]

| Name of buildings | Commune |

|---|---|

| Moulin du Puy bridge | Celles-sur-Durolle |

| Celles bridge | |

| Chazeau bridge | La Monnerie-le-Montel |

| Tuileries bridge | |

| Membrun bridge | Thiers |

| Vielh bridge | |

| Saint-Roch bridge | |

| Seychalles bridge | |

| Saint-Jean bridge | |

| Ferrier bridge | |

| Navarron bridge | |

| Ship bridge | |

| Bridgnorth bridge |

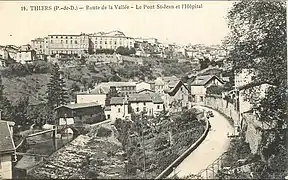

Thiers old hospital

Built in the 17th century, the Old Thiers Hospital is located in the eastern part of the historic center of Thiers, France. The site covers an area of 0.5 ha, and the buildings cover more than 7,000 m2.[30] The chapel has been listed as a historic monument since 1979. Like the rest of Thiers' old town, the site has underground structures and cellars. Closed in 1988 following the hospital's move to new premises at the Thiers hospital center, the site remained partially abandoned before being completely abandoned following the departure of the medical-psychological consultation center in 2016.[31][32]

It overlooks the Durolle valley at the level of the Vallée des Usines and the hospital garden, which was once managed and maintained by the hospital's nuns.[33]

Thiers ramparts

The Thiers ramparts are fortifications built between the 11th and 16th centuries to protect the town of Thiers.[34] From the 11th century onwards, the town grew in concentric circles around the ramparts of the castle of the Lord of Thiers and the church of Saint-Genès. As new towns were added around the city walls, the walled city expanded at least five times.[35] The less well-maintained parts of the various walls were demolished at the end of the eighteenth century, but it was above all the urban development of the nineteenth century that led to the demolition of several segments of the northern wall and the reallocation of the eastern wall. In the 19th century, only the eastern part of the fortifications remained intact.[35] In particular, it served as a retaining wall to hold back soil from the city's slopes.[35][36]

Much of the fourth and all of the fifth fortifications can be seen from the Durolle riverbed, as both were built in the upper reaches of the Durolle valley.[3]

Activities

Industry

Although some of the workshops, cutlery factories and spinning wheels are now closed, some are still in operation. The C.A.P plastiques factory, still in operation near Creux de l'enfer,[37] is located next to a Wichard factory also still in operation.[38] Other companies are still present in the Durolle valley, such as the CEP agriculture plant.[39]

Fishing

As long as industrial activity was strong in the valley, water quality in the Durolle was mediocre.[14] But as factories closed down, the quality of water taken from the river improved significantly. This marks the return of the trout, which is particularly sensitive to water quality. Their environment needs to be highly oxygenated, fresh and of good quality.[14][15] Although the number of licensed anglers in France has been declining for several years, and fishing in the Durolle canyons is risky because of the river's development (old factories, dykes, paddle wheels, sharp metal remains in the water, cliffs and trees), the trout fishing season near Le Creux de l'enfer attracts a large number of enthusiasts every year.[14] This part of the Durolle valley is renowned as a street fishing site, i.e. a place where fishing is practised in town.[40]

Tourism

Cultural tourism

The heritage interest of the Durolle valley attracts the attention of Thiers town council and tourists alike. Indeed, the Vallée des Usines is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Thiers region.[41] In fact, the valley has been awarded a two-star rating by the Michelin Green Guide, with the words "Mérite le détour (Worth a detour)".[42]

The gardens of the former hospital, restored in 2007, are remarkable for their terraced layout and the view they offer over the Vallée des Usines.[43] The Centre d'Art Contemporain du Creux de l'Enfer is an artistic production center offering exhibition programs including sculptures, installations, paintings, photographs, videos and performances.[44] With a program of national and international stature, it plays an active role in the cultural life of the town, the Puy-de-Dôme department and the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, and works to raise artistic awareness with over two thousand school visitors every year.[44] The May factory is a space dedicated to culture, for temporary exhibitions, artist residencies, special events and educational support.[45] The logis abbatial du Moutier, comprising the abbey of the same name and the church of Saint-Symphorien, dates from the 11th century. The abbey can be visited from 1 July to 31 August, while the church is open to the public all year round.[46][47]

Ecotourism

Marked hiking trails run along the Durolle riverbed. They allow hikers to discover landscapes of valleys and volcanic peaks, such as the Vallée des Rouets.[48] On these circuits, panels explain and present several plant species found in the Durolle canyons. Others, like the Margerides trail, follow the course of the Durolle without coming close to it, but overlooking it.[49]

Protection

The Durolle valley is part of the Livradois-Forez Regional Natural Park.

The Durolle canyons are partly protected by the ZNIEFF (Zone naturelle d'intérêt écologique, faunistique et floristique by its extension [Natural area of ecological, faunal and floristic interest]).[50] In fact, the numerous plant and animal species present in the river valleys are considered "fairly interesting from a heritage point of view".[50]

The Durolle valley is partially protected by the Thiers conservation and development plan of December 1980.[51] Only the western part of the valley is covered by this plan.[52] It is also protected by the town's local urban development plan.[53]

The valley also boasts a number of buildings protected as historic monuments. These include the May factory, the Mondière forges, the Seychalles bridge, the Saint-Jean church in Thiers and the Moutier abbey.[54]

In the arts

The Creux de l'Enfer art center publishes a pocket-sized collection entitled "Mes pas à faire au Creux de l'Enfer". It accompanies the annual exhibition cycle "Les Enfants du Sabbat" with the participation of Clermont Auvergne Métropole and the Lyon Metropolis.[55] It also co-produces books by artists who have exhibited their work in the building, including Mona Hatoum in 2000, Pierre Ardouvin in 2004, Didier Marcel in 2006, Franck Scurti in 2010 and Armand Jalut in 2012.[56] In 2017, painter Mireille Fustier painted the old cutlery factory and its waterfall. Inspired by local landscapes, she takes an interest in the buildings of the Vallée des Usines, particularly the Creux de l'enfer factory.[57]

In her book La ville noire, George Sand describes the Durolle and its factories on several occasions. She describes the Creux de l'enfer factory as a site that is still called the "val d'enfer" or the "passage des fées", and is even named "au bord du saut d'enfer". She also recounts how, when the May factory was set on fire (a frequent occurrence in the Durolle canyons) a woman and her children threw themselves into the swirling torrent to escape the flames.[58]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sandre. "Fiche cours d'eau – la Durolle (K29-0310)" (in French). Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Rivière Dore – Dictionnaire des canaux et rivières de France". projetbabel.org (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Combe, Paul (1922). "Thiers et la vallée industrielle de la Durolle". Annales de géographie (in French). 31 (172): 360–365. doi:10.3406/geo.1922.10136. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ↑ Guilhòt, Josí (2009). Femnas : femnas dins lo silenci del temps. Racontes (in Occitan). Ostal del Libre ; Institut d'études occitanes. p. 140.

- 1 2 "Source de la Durolle". Géoportail (in French). Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Géoportail; IGN. "Géoportail" (in French). Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- 1 2 "Confluence de la Durolle avec la Dore". Géoportail (in French). Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Albin, Anne-Flore (2016). "Étude des crues soudaines sur les bassins versants du Sichon-Jolan dans l'Allier et de la Couze-Chambon, de la Couze-Pavin et de la Durolle dans le Puy de Dôme" (PDF). p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Association Le pays Thiernois (1990). Le pays thiernois et son histoire (in French). pp. 33, 34.

- 1 2 Cubizolle, Hervé (1997). La Dore et sa vallée: approche géohistorique des relations homme-milieu fluvial (in French). Université de Saint-Etienne. ISBN 9782862721040.

- 1 2 3 Cartographe Bouiller, Robert (1976). Carte géologique de la France à 1/50 000. 694, Thiers (in French). Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières.

- ↑ Carte géologique de la France (in French). Thiers: BRGM. p. 66. ISBN 9782715916944.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gorges de la Durolle" (PDF). inpn.mnhn.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Centre France. "A quelques pas du centre-ville, des recoins peu accessibles permettent de taquiner la truite". www.lamontagne.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- 1 2 "La Durolle dans Thiers". Fédération du Puy de Dôme pour la Pêche et la Protection du Milieu Aquatique (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Histoire de la Ville : Office de Tourisme de Thiers". www.thiers-tourisme.fr (in French). Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ↑ "La vallée des usines – Balades dans le Puy-de-Dôme". canalblog (in French). 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ↑ Drillon, Caroline; Ricard, Marie-Claire (2012). L'Auvergne Pour les Nuls (in French). edi8. ISBN 9782754044851.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Combe, Paul (1922). "Thiers et la vallée industrielle de la Durolle". Annales de Géographie (in French). 31 (172): 360–365. doi:10.3406/geo.1922.10136. ISSN 0003-4010. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ↑ "Au Sabot". ausabot.com (in French). Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ Littré, Émile. "Cacheur". Dictionnaire de la langue française (in French). Archived from the original on 2020-06-30. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- 1 2 3 Hadjadj, Dany (1999). Pays de Thiers: le regard et la mémoire (in French). Presses Univ. Blaise Pascal. p. 267. ISBN 9782845161160.

- 1 2 Jubertie, Fabien (2007). Les excès climatiques dans le Massif central français. L'impact des temps forts pluviométriques et anémométriques en Auvergne (PDF) (in French). p. 435.

- 1 2 Ponchon, Henri (2007). Mémoire d'Augerolles et la Renaudie (in French). Éditions de la Montmarie. p. 287. ISBN 978-2-915841-32-9.

- ↑ Vital-Merle (instituteur public.); Desdevises du Dezert, Georges Nicolas (1933). Sur l'Auvergne: notes, documents, extraits d'histoire et de géographie (in French).

- 1 2 3 4 "Un privilège seignerial | Conservatoire National du Saumon Sauvage". www.saumon-sauvage.org (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ Combe, Paul (1956). Thiers: les origines, l'évolution des industries thiernoises, leur avenir (in French). G. de Bussac.

- ↑ "Église Saint-Antoine de Padoue". Eglise info (in French). Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "L'ancien hôpital". www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ Senzier, Thierry (2017). "Conseil municipal – L'aménagement des abords devrait démarrer bientôt". La Montagne (in French). Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ↑ Jaulhac, François (2018). "En avant 2018 – Une année 2018 placée sous le signe de la construction à Thiers". La Montagne (in French). Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ↑ "Jardins de l'Ancien Hôpital". pentalocal (in French). Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Office de tourisme de Thiers" (PDF). www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 Service régional de l’Inventaire Auvergne (2014). Thiers, suivre la pente (PDF) (in French).

- ↑ Centre France. "De la place du Corps-de-Garde à la place Saint-Jean, la rue des Murailles longe la Durolle". www.lamontagne.fr (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "C.A.P Thiers". www.societe.com (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Des entreprises et espaces culturels apportent du dynamisme à l'avenue Joseph-Claussat". La Montagne (in French). 2012.

- ↑ "Etablissement CEP AGRICULTURE". www.societe.com (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ Comité de pêche du Puy-De-Dôme. Vallée de la Durolle (PDF) (in French). Comité de pêche du 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- ↑ "La vallée des Usines". www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Thiers – Vallée des Usines – Le Guide Vert Michelin". voyages.michelin.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "Les jardins dessous Saint-Jean". www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- 1 2 Le Creux de l’enfer. "Le Creux de l'enfer". www.creuxdelenfer.net (in French). Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "L'usine du May". www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Chateaux :: Office de Tourisme de Thiers". www.thiers-tourisme.fr (in French). Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "EGLISE SAINT-SYMPHORIEN-DU-MOÛTIER". www.auvergne-tourisme.info (in French). Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "Planète Puy de Dôme : tourisme et vacances dans le Puy-de-Dôme – Auvergne". www.planetepuydedome.com (in French). Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "THIERS randonnée pédestre trace gps puy-de-dome". www.randogps.net (in French). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- 1 2 "INPN, ZNIEFF – Gorges de la Durolle". inpn.mnhn.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ↑ Dubreuil, JP Louis (2018). Ville de Thiers : site patrimonial remarquable (PDF) (in French). p. 30.

- ↑ Ville de Thiers. Plan de Sauvegarde et de mise en valeur de Thiers (in French). 1980. Archived from the original on 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- ↑ "Plan local d'urbanisme" (PDF). www.ville-thiers.fr (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Base de mérimée". www2.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "Éditions (le Creux de l'enfer)". www.creuxdelenfer.net (in French). Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "Librairie (le Creux de l'enfer)". www.creuxdelenfer.net (in French). Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ "À Thiers, le Creux de l'Enfer est le paradis du peintre pour Mireille Fustier". www.lamontagne.fr (in French). 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ↑ "Histoire et mémoire du lieu (le Creux de l'enfer)". www.creuxdelenfer.net (in French). Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

Bibliography

- Lefebvre, Magali; Chabanne, Jérôme; Le musée de la coutellerie (2005). Vallée des usines (in French). Ville de Thiers. ISBN 9782351450086.

- Combe, Paul (1922). Thiers et la vallée industrielle de la Durolle (in French). A. Colin.

- Combe, Paul (1956). Thiers : les origines, l'évolution des industries thiernoises, leur avenir (in French). G. de Bussac.

- Hadjadj, Dany (1999). Pays de Thiers : le regard et la mémoire (in French). Presses Univ Blaise Pascal. ISBN 9782845161160.

.jpg.webp)

-0671.jpg.webp)