The Dutch Nul Group, which consisted of Armando (b. 1929), Jan Henderikse (b. 1937), Henk Peeters (b. 1925-2013) and Jan Schoonhoven (1914-1994), manifested itself in form and name in 1961. On 1 April 1961, a stone's throw from the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, Galerie 201 organized the ‘Internationale tentoonstelling van NIETS’ ('International Exhibition of NOTHING’). The 'Manifest tegen niets' ('Manifesto against Nothing') and 'Einde' ('Ending'), a pamphlet published at the same time, were among the first activities of the Nul group.[1] ‘We need art like we need a hole in the head,’ the pamphlet 'Einde' states; ‘From now on the undersigned pledge to work to disband art circles and close down exhibition facilities, which can then finally be put to worthier use.’ [2] The 'Einde' pamphlet imagines a new beginning, as Armando and Henk Peeters had already proclaimed in texts written several years earlier for the Dutch Informals.[3]

Roots of Nul: The Dutch Informal Group

The Dutch Informal Group, preceding the formation of the Nul group, was founded in 1958.[4] Until early 1961 its members showed works in oils or pigments mixed with plaster and sand, usually on panels, linen or jute. The group replaced the expression of emotions in paint with an attempt at an absence of 'personal signature', resulting in colourless and monochrome works virtually devoid of form or composition. In 1958 Henk Peeters saw the work of Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri for the first time, at the Venice Biennale. Fontana's escape ‘from the prison of the flat surface’ by piercing or slicing up the canvas and Burri's material, burnt plastic, made a big impression on him.[5] Burri and Fontana played a vital role in the transition from paint on canvas or panel to the use of industrial materials and the abandonment of the flat surface. Barely a year later, in 1959, Henk Peeters burned two rows of holes in a painting, 1959-03, and Armando set nails in the ends of a panel, Espace Criminal (10 zwarte spijkers op zwart; 10 Black Nails on Black). These works marked a transitional phase from the informal painting to Nul work; they are iconoclastic intermediate steps Peeters and Armando were taking on their new path.[6] Henderikse also turned his back on painting in 1959, with assemblages of everyday objects, and toward 1960 Schoonhoven strived, in frozen, increasingly whiter reliefs, ‘by avoiding intentional form . . . for a much greater organic reality of the artificial in and of itself.’ These are works that, according to Schoonhoven, offer the possibility ‘to arrive at [an] objectively neutral expression of the generally applicable.’[7]

The International Context

Armando, Jan Henderikse, Henk Peeters and Jan Schoonhoven first exhibited their new, non-painting work at the ‘Internationale Malerei 1960-61’ exhibition in Wolframs-Eschenbach, Germany.[8] The first issue of the new group's internationally oriented ‘house organ’, the journal Revue nul = 0, edited by Armando, Henk Peeters and Herman de Vries, came out in November 1961.[9] With contributions by artists who a year later would take part in the first Nul exhibition at the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum,[10] the journal presented a good overview of the main themes of the international ZERO movement, which emerged around the journal ZERO, published in 1958 and 1961 by German artists Heinz Mack en Otto Piene.[11] The movement found sympathizers in countries like Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and Venezuela. Since the late 1950s the Dutchmen had established close ties with the German Zero group led by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene (Günther Uecker joined the group in 1961) and the Japanese group Gutai, as well as with Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani, the French Nouveau Réaliste Yves Klein and Japan's Yayoi Kusama.

The Identity of Nul

Nul's pragmatism, its sober approach to the world, to the product of art, to being an artist and to reality, is expressed in the formal characteristics of its works, but also in its everyday practice, in the way works were created and exhibited, the way artists operated and presented themselves. The Nul artists aimed to shed the stereotyped image of the bohemian in a painting smock and had a fresh attitude toward the consumer society, quite at odds with the artistic scene of the early 1960s. Nul was a search for new relationships between art and reality, with at its base the rejection of uniqueness, authenticity and decorative attractiveness in the traditional sense of the word. The group reduced the multi-coloured to the monochrome and opted for repetition, seriality and the directness of everyday materials and objects, in use and effect. Even its conceptual aspect, the splitting of thought and action, of conception, production as well as the possibility of repeat production was, in the footsteps of Marcel Duchamp, linked to a different interpretation of ideas like craftsmanship and expertise. At the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum in 1962, for instance, Armando and Jan Henderikse left the setting up of their installations to museum staff, and in 1965, at Peeters's request, Yayoi Kusama produced a work in his material, card sliver, a spun synthetic fibre. ‘The process of creation is . . . completely unimportant and uninteresting; a machine can do it,’ Peeters said. ‘The personal element lies in the idea and no longer in the manufacture.’[12] The identity of the Dutch Nul group navigated between a cheerful orientation toward the world of the everyday and the cool sobriety of the serial monochrome. Whereas the German Zero artists were still ‘painting’ with the elements, with the effects of fire, light, shadow, movement and reflection, the Nul artist preferred to let reality speak for itself by isolating it, usually in raw form. Among the Dutchmen, only Henk Peeters worked with the elements water and fire – although Peeters saw his ‘pyrographs’, soot and scorch marks on various surfaces, as a typically Nul solution to the elimination of any excessively personal element: to work with the fickleness of a flame is ‘. . . to let go of the work and to become the spectator of a self-directed performance.’[13] In terms of form, Peeters's tactile cotton balls, whether on a canvas or on a wall as a three-dimensional installation, are balanced on the cusp between Nul and the German Zero. 'It is not our job to educate, any more than it is our job to convey messages,’ said Piero Manzoni in 1960.[14] This might as easily have been a statement by Henk Peeters, by Jan Henderikse and even by the German Zero group. And yet the sober-minded outlook of the Dutchmen distinguished itself from the German Zero. ‘Yes, I dream of a better world. Should I dream of a worse?’ wrote Otto Piene in ‘Paths to Paradise’ in 1961.[15] With their clear-eyed view of reality, the members of Nul were not dreaming of the world, neither a better nor a worse, and certainly not of ‘paths to paradise’. During the Nul period, radicalism and a sincerely felt admiration for what was new and contemporary went hand in hand; nimble provocation is what Nul seemed to have a patent on.

The Monochrome

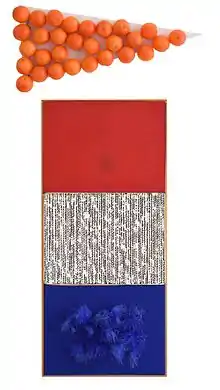

Jan Schoonhoven’s ‘objectively neutral expression of the generally applicable’ persisted throughout Nul, and in his work, monochrome – the reduction of all colour to white – was the chosen instrument. Henk Peeters also considered monochrome a levelling effect that could bridge contradictions across the two-dimensional plane, although his work was never as explicitly monochrome as Jan Schoonhoven's. Armando saw a straight line from his monochrome oil paintings of the late 1950s to his assemblages of bolts and barbed wire during the Nul period. In both instances, to Armando, monochrome was a farewell to the psychology of the maker; the monochrome surface is frozen and anonymous – as far as it goes. In Jan Henderikse’s work monochrome played a far more modest role, although in 1959 he was already painting his earliest assemblages black. Mass and multiplication were Henderikse’s major methods of reducing the personal element: ‘I hate little stories but I really love a lot of stuff, of all those things people love, everyday things especially. It’s always been that way.’[16]

The Grid

Archetypal Nul work seems constructed out of a multiplication of uniform and isolated forms, objects or phenomena: as repetitions of steel bolts, of matchboxes, of identical white surfaces grids of burn holes and cotton balls. In 1965 Schoonhoven made bold pronouncements on seriality, on the repeated pattern of identical elements. Organization ‘. . . comes out of the need to avoid partiality’ and had nothing to do with geometric structure. To Jan Schoonhoven, Nul's method was driven by its intentions, by the consistent acceptance of isolated reality without accentuating any one thing, with no high points or low points. Armando spoke of ‘intensifying one of the elements out of which a painting used to be constructed’, because ‘. . . combining fragments is an obsolete method.’ Seriality was their common way of expressing their refusal to compose, although each found his own material and method: Armando's seriality is more frozen than Henderikse's, harder than that of Peeters and more direct in material than Schoonhoven's.

The Everyday and the Ordinary

Even machine-made objects and materials proved ideal for taking the personality aspect out of the work. The choice was not linked to any deeper notion; the material is most of all ‘itself’ in all its ordinary beauty. This acceptance of reality implied that the contribution of the artist, aside from making the choice, was often reduced to a minimum. In 1960 Jan Henderikse signed Düsseldorf's Oberkassel Bridge in whitewash; three years later he made plans to sign a HEMA shop in Amsterdam, to turn it into the biggest ready-made assemblage ever. These are examples of radical adaptations of reality, like Armando’s 1964 installation of oil drums at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in The Hague. According to the Nul artist, there was little you could do to improve on a piece of isolated reality in its unadulterated form. ‘Everything was beautiful’, Armando said in 1975. ‘Everything was interesting. One big eye, that’s how I felt.’[17] For Henk Peeters, the choice of synthetic products and plastic cut both ways. The material was free of visual signature, but it was also emphatically unpainterly and an expression of resistance against the academic establishment and the rules of the game. To undermine the retinal aspect of art, the precious and status-based object as a fetish for the eye, Peeters envisaged one more method: to bypass ‘seeing’ altogether and appeal to the sense of touch. Peeters's ‘tactilist’ works of cotton wool, feathers, hair pieces, nylon thread or fake fur are ‘objects of greater interest to senses other than the eye.’ Jan Schoonhoven is the only one who never ‘annexed’ objects or ready-made materials. Schoonhoven saw his reliefs as ‘spiritual reality’, as a representation of forms out of reality and therefore, in a roundabout way, fitting within the Nul idiom. One exception to the rule was his wall of folded and stacked boxes in the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in The Hague in 1964. If we take a signatureless use of industrially produced material as a requisite, this is Schoonhoven's only ‘pure’ Nul work – not to mention directly taken from reality, since Schoonhoven had spotted the stacked boxes in the attic of the Historic paint factory.

Research

The 0-INSTITUTE, founded in 2005, has the task of researching, preserving and presenting the works and documents of artists associated with the international post-war ZERO movement and active in to evaluate the ideas of the movement and present them in a contemporary context. The ZERO foundation was established in 2008 - upon an initiative by the Dutch curator Mattijs Visser-, a collaboration between the Düsseldorf ZERO artists with the Museum Kunstpalast. The ZERO foundation has the task of researching, preserving and presenting the works and documents of the German Zero group.

Recent attention for Nul and ZERO

In 2014 and 2015, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum organized the exhibition 'ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s' (October 2014-January 2015), paying tribute to the international ZERO movement and its artists. This exhibition was followed by the traveling exhibitions 'ZERO. Die Internationale Kunstbewegung der 50er und 60er Jahre' (Museum Martin-Gropius-Bau, March–June 2015) and 'ZERO. Let us Explore the Stars' (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, July–November 2015), both organized in conjunction with the Düsseldorf based ZERO foundation. Over the last years, several European galleries hosted exhibitions on the Dutch Nul-artists. Most notably are however London based The Mayor Gallery and Borzo Gallery in Amsterdam, especially for their longstanding interest in ZERO, Nul and minimal tendencies. The Mayor Gallery hosted several Nul-related exhibitions, including works by Armando (2007, 2010, 2012), Henk Peeters (2011), and a group show of the four Nul-members under the title 'Nul=0' (2007, Armando, Jan Henderikse, Henk Peeters and Jan Schoonhoven; this exhibition in conjunction with Borzo Gallery, Amsterdam). Armando was also included in the 2010 show 'zero+' (Armando, Dadamaino, Lucio Fontana, Gerhard von Graevenitz, Otto Piene, and Luis Tomasello).

References

- ↑ 'The Manifest tegen niets' was signed by Armando, Bazon Brock, Jan Henderikse, Arthur Køpcke, Carl Laszlo, Silvano Lora, Piero Manzoni, Christian Megert, Onorio, Henk Peeters and Jan Schoonhoven; the pamphlet 'Einde' by Armando, Bazon Brock, Jan Henderikse, Arthur Køpcke, Silvano Lora, Piero Manzoni, Christian Megert, Henk Peeters and Jan Schoonhoven. The manifesto and the pamphlet were sent in the form of an invitation to the 'Internationale tentoonstelling van NIETS' in the Amsterdam Galerie 207, April 1961. The 'Manifest tegen niets' was based on a publication of the same name by Carl Laszlo (Basel, 1960), also publisher of the influential Swiss magazine Panderma.

- ↑ 'Einde', pamphlet, 1 April 1961'

- ↑ Armando had published his texts 'Credo 1' and 'Credo 2' in 1958 and 1959, respectively. Henk Peeters, 'Vuil aan de lucht', published in Nederlandse Informele Groep, ex. cat. (Arnhem: self-publication, 1959), no page numbers. Peeters text was published at the occasion of the exhibition 'Nederlandse Informele Groep' at the Nijmegen Besiendershuys, July 4–20, 1959. For how Peeters’ early artist’s texts were received, see also: Jonneke Jobse, 'Houdt links!,' in: Jonneke Jobse and Marga van Mechelen (eds.), Echt Peeters. Henk Peeters, realist, avant-gardist (Wezep: Uitgeverij de Kunst, 2011), 33-41.

- ↑ Also Dutch artists Fred Sieger (1902-1999) and Rik Jager (1933) participated in exhibitions of the Dutch Informal Group. Bram Bogart (1921-2012) only took part in the very first exhibition, at the refectory of the Delft University, in 1958. Kees van Bohemen (1928-1985) left the group in February 1961. See also: Franck Gribling, Informele Kunst in Belgie en Nederland 1955-'60, exhibit. cat. (The Hague: Gemeentemuseum/Antwerp, Koninklijk Paleis voor Schone Kunsten, 1983), 16.

- ↑ Antoon Melissen, 'Nul = 0. The Dutch avant-garde of the 1960s in a European Context', in: Colin Huizing and Tijs Visser, eds., The Dutch Nul Group in an International Context, (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2010), 13-14.

- ↑ Antoon Melissen, ed., Armando. Between Knowing and Understanding, (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2015), 66-68.

- ↑ Jan Schoonhoven, untitled text, 1960. Published at the occasion of the first exhibition of the Dutch Informal Group outside the Netherlands, at Galerie Gunar, Düsseldorf. In: Nederlandse Informele Groep, brochure, 1960, no page numbers.

- ↑ Bram Bogart and Kees van Bohemen also took part in this exhibition. See Het Vaderland, 8 March 1961

- ↑ nul = 0. tijdschrift voor de nieuwe konseptie in de beeldende kunst, series 1, no. 1 (November 1961). The first issue of the magazine nul = 0 was edited by Armando, Henk Peeters and Herman de Vries and published in French and German. Another three issues would follow; number two in 1963 without Armando as editor, and numbers three and four in 1963-1964, under the slightly altered title revue nul = 0, with Herman de Vries as the sole editor.

- ↑ 'Nul', March 9–26, 1962, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Participating artists were Armando, Bernard Aubertin, Pol Bury, Enrico Castellani, Dadamaino, Piero Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hermann Goepfert, Hans Haacke, Jan Henderikse, Oskar Holweck, Yayoi Kusama, Francesco Lo Savio, Heinz Mack, Piero Manzoni, Almir Mavignier, Christian Megert, Henk Peeters, Otto Piene, Uli Pohl, Jan Schoonhoven, Günther Uecker, Jef Verheyen and Herman de Vries. Henk Peeters played a guiding role in the initiation and organization of the exhibition. Although Herman de Vries had not co-signed manifestoes and pamphlets drawn up by Armando and Henk Peeters, nor taken part in the exhibitions under the flag of the Nederlandse Informele Groep, prior to the formation of the Nul Group in 1961, his work was nonetheless an important component of the Dutch presentation in the 1962-exhibition Nul, in a gallery together with Henderikse, Peeters and Schoonhoven.

- ↑ The three issues of the ZERO journal were published in April 1958, October 1958 and July 1961.

- ↑ Antoon Melissen, (see note 5), 16.

- ↑ Henk Peeters, untitled contribution to the catalogue Nul negentienhonderd vijf en zestig, part II, no page numbers. This catalogue accompanied the second large scale ZERO exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, spring 1965.

- ↑ Germano Celant, Piero Manzoni, ex. cat., (Milan: Charta/London: Serpentine Gallery, 1998), 271.

- ↑ Otto Piene, 'Paths to Paradise (Wege zum Paradies), in: Heinz Mack and Otto Piene (eds.), ZERO, Cambridge (MA)/London: MIT Press, 1973), 146.

- ↑ Antoon Melissen, (see note 5), 15.

- ↑ Armando, quoted in: Janneke Wesseling, Alles was mooi. Een kleine geschiedenis van de Nul-beweging, (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/The Hague: Landshoff, 1989), 7.