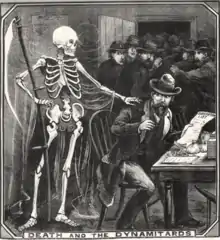

A dynamitard was a person who used explosives for violence against the State, and is a niche metaphor for a revolutionary in politics, culture or social affairs.

Bombers

First appearing in English language newspapers in 1882,[1][2][3] the word was understood to be a French expression applied to political terrorists in France.[4] In reality, dynamitard is not a formal French word; French newspapers had conjured it up as a disdainful variant of dynamiteur.[5] It was soon applied to Burton and Cunningham,[6] Irish-Americans who had planted explosives in London.[4][7] "A term of opprobrium for some and endearment for others, the dynamitard was technically a political dynamiter, of the kind that bombed railway carriages and exploded devices in the House of Commons in the name of Irish freedom, chiefly in the early 1880s."[8]

Metaphorical sense

In nineteenth century politics the term came to be used, particularly by George Bernard Shaw, as metonymy for those who chose violent struggle — as opposed to gradual means — for achieving social revolution: a dynamitard was contrasted with a Fabian.[9][10] Shaw himself, though a Fabian in politics, was described metaphorically as "a dynamitard among music and drama critics".[11]

In popular culture

Between 1889[12] and 1903[13] Stevenston Thistle, who played in the Ayrshire Football League and elsewhere,[14] were known as The Dynamitards.[15] They did not live up to their name, however, losing 7-2 to Clyde F.C. in the first round of the 1894–95 Scottish Cup.

In high culture

Mocked as a neologism by Robert Louis and Fanny van de Grift Stevenson ("Any writard who writes dynamitard shall find in me a never-resting fightard"),[16] its presence in dictionaries regretted by purists,[17] there it has remained.

References

- ↑ Pall Mall Gazette 1882, p. 1.

- ↑ Glasgow Herald 1882, p. 6.

- ↑ Manchester Evening News 1882, p. 2.

- 1 2 Manchester Evening News 1883, p. 2.

- ↑ Glaser 1910, p. 946.

- ↑ The Times 1885, p. 12.

- ↑ Luton Times and Advertiser 1885, p. 7.

- ↑ Burton 2015, p. 348.

- ↑ Laurence 1954, p. 8.

- ↑ Wallmann 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ Gassner 1962, p. 519.

- ↑ Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald 1889, p. 3.

- ↑ Scottish Referee 1902, p. 2.

- ↑ Historical Football Kit c. 2019.

- ↑ McDowell 2010, p. 113.

- ↑ Stevenson & van de Grift Stevenson 1885, p. 183.

- ↑ The Times 1950, p. 7.

Sources

Books, journals and theses

- Burton, Antoinette (2015). "Review: The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867– 1900 by Niall Whelehan: Alter-Nations: Nationalisms, Terror and the State in Nineteenth-Century Britain and Ireland by Amy E. Martin". Victorian Studies. Indiana University Press. 57 (2): 348–50. doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.57.2.348. JSTOR 10.2979/victorianstudies.57.2.348.

- Gassner, John (1962). "Bernard Shaw and the Making of the Modern Mind". College English. National Council of Teachers of English. 23 (7): 517–525. doi:10.2307/373086. JSTOR 373086.

- Glaser, Kurt (1910). "Le sens péjoratif du suffixe-ard en français". Romanische Forschung (in French). Vittorio Klostermann GmbH. 27 (3): 932–982. JSTOR 27935761.

- Laurence, Dan H. (1954). "Bernard Shaw and the Pall Mall Gazette: An Identification of His Unsigned Contributions". Bulletin (Shaw Society of America). Penn State University Press (6): 1–7. JSTOR 40681278.

- McDowell, Matthew Lynn (2010). "The origins, patronage and culture of association football in the west of Scotland, c. 1865-1902. PhD thesis" (PDF). University of Glasgow theses. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis; van de Grift Stevenson, Fanny (1885). More New Arabian Nights: the Dynamiter. Leisure hour series,no. 162. New York: Henry Holt. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Wallmann, Jeffrey M. (1997). "Evolutionary Machinery: Foreshadowings of Science Fiction in Bernard Shaw's Dramas". Shaw. Penn State University Press. 17, SHAW AND SCIENCE FICTION: 91–95. JSTOR 40681465.

Newspaper reports and websites

- "The Red Spectre in France". Pall Mall Gazette. London. 28 October 1882.

- "Monday morning, October 30". Glasgow Herald. 30 October 1882.

- "Evening News". Manchester Evening News. 31 October 1882.

- "From our London Correspondent". Manchester Evening News. 7 April 1883.

- "The Dynamite Outrages". The Times. 10 February 1885.

- "Miscellaneous". Luton Times and Advertiser. 13 March 1885.

- "Sports". Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald. 4 October 1889.

- "Ayrshire Notes". Scottish Referee. 21 November 1902.

- "Derivations". The Times. 17 March 1950.

- Historical Football Kit. "Eminent Victorians". Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2019.