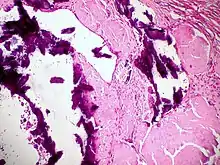

Dystrophic calcification (DC) is the calcification occurring in degenerated or necrotic tissue, as in hyalinized scars, degenerated foci in leiomyomas, and caseous nodules. This occurs as a reaction to tissue damage,[1] including as a consequence of medical device implantation. Dystrophic calcification can occur even if the amount of calcium in the blood is not elevated, in contrast to metastatic calcification, which is a consequence of a systemic mineral imbalance, including hypercalcemia and/or hyperphosphatemia, that leads to calcium deposition in healthy tissues.[2] In dystrophic calcification, basophilic calcium salt deposits aggregate, first in the mitochondria, then progressively throughout the cell. These calcifications are an indication of previous microscopic cell injury, occurring in areas of cell necrosis when activated phosphatases bind calcium ions to phospholipids in the membrane.

Calcification in dead tissue

- Caseous necrosis in T.B. is most common site of dystrophic calcification.

- Liquefactive necrosis in chronic abscesses may get calcified.

- Fat necrosis following acute pancreatitis or traumatic fat necrosis in breasts results in deposition of calcium soaps.

- Infarcts may undergo D.C.

- Thrombi, especially in veins, may produce phleboliths.

- Haematomas in the vicinity of bones may undergo D.C.

- Dead parasites like schistosoma eggs may calcify.

- Congenital toxoplasmosis, CMV or rubella may be seen on X-ray as calcifications in the brain.

Calcification in degenerated tissue

- Dense scars may undergo hyaline degeneration and calcification.

- Atheroma in aorta and coronaries frequently undergo calcification.[3][4]

- Cysts can show calcification.

- Calcinosis cutis is condition in which there are irregular nodular deposits of calcium salts in skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- Senile degenerative changes may be accompanied by calcification.

- The inherited disorder pseudoxanthoma elasticum may lead to angioid streaks with calcification of Bruch's membrane, the elastic tissue below the retinal ring.

See also

References

- ↑ "Cell Injury".

- ↑ Elgazzar AH (2011) [Originally published 2004]. "Chapter 8: Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Calcification". Orthopedic Nuclear Medicine. Springer-Verlag. pp. 197–210. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-18790-2_8. ISBN 978-3-642-18790-2.

- 1 2 Bertazzo, Sergio; Gentleman, Eileen; Cloyd, Kristy L.; Chester, Adrian H.; Yacoub, Magdi H.; Stevens, Molly M. (Jun 2013). "Nano-analytical electron microscopy reveals fundamental insights into human cardiovascular tissue calcification". Nature Materials. 12 (6): 576–583. Bibcode:2013NatMa..12..576B. doi:10.1038/nmat3627. PMC 5833942. PMID 23603848.

- ↑ Miller, Jordan D. (Jun 2013). "Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins". Nature Materials. 12 (6): 476–478. Bibcode:2013NatMa..12..476M. doi:10.1038/nmat3663. PMID 23695741.