| Eadric | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Kent | |

| Reign | 685?–686 |

| Died | 686 or 687 |

| Father | Ecgberht |

Eadric (died August 686/ 687?) was a King of Kent (685–686). He was the son of Ecgberht I.

Historical context

In the 7th century the Kingdom of Kent had been politically stable for some time. According to Bede:

In the year of our Lord 640, Eadbald king of Kent, departed this life, and left his kingdom to his son Eorcenberht, which he most nobly governed twenty-four years and some months.

— Bede 1910, HE III.8

Eorcenberht was succeeded by his sons Ecgberht (664-673) and Hlothhere (673-685).[1] Ecgberht's court seems to have had many diplomatic and ecclesiastic contacts. He hosted Wilfrid and Benedict Biscop, and provided escorts to Archbishop Theodore and Abbot Adrian of Canterbury for their travels in Gaul.[2] However, increasing dynastic tensions occurred at this time, when according to tradition Ecgberht had his cousins Æthelred and Æthelberht murdered, effectively removing them as they had a strong claim on the throne.[1]

| Eorcenberht's family tree (Date of reign) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Joint ruler of Kent?

Hlothhere succeeded his brother as ruler of Kent in 673.[3] It was not unusual for Kent to be divided between rulers at that time.[3] However although there has been some suggestion that Eadric jointly ruled with his uncle Hlothhere, there is no certain evidence for it.[2] The Law of Hlothhere and Eadric is a single law code that was issued in the name of Hlothhere and Eadric as joint rulers of Kent, but it may just have been a conflation of two earlier separate codes.[lower-alpha 1][2][4]

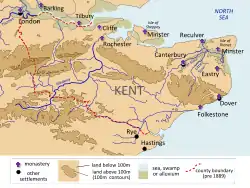

In 679 Hlothhere granted land in Thanet to Beorhtwald, abbot of Reculver.[lower-alpha 2] In the charter document there is a statement noting the agreement of Archbishop Theodore and "Eadric, son of my brother". [lower-alpha 3]

Sole ruler

The charter of 679 implies that, at that date, the relationship between Eadric and his uncle were not unfriendly, however in about 685 Eadric revolted against his uncle. With help from Æthelwealh of Sussex he raised a South Saxon army and defeated Hlothhere in battle. Hlothhere died of his wounds shortly after and Eadric became sole ruler of Kent.[6][2]

Eadric was a nephew of Wulfhere of Mercia. Wulfhere was in an alliance with the South Saxons, so it would have served the politics of the time for Æthelwealh to support Eadric's coup against Hlothhere.[2]

Invaded by Wessex

Also, in 685 a West Saxon warband invaded Sussex under the command of the Wessex prince Cædwalla and killed Æthelwealh. Cædwalla was subsequently driven out of Sussex by two of Æthelwealh's ealdormen, Berhthun and Andhun. William of Malmesbury suggests that Eadric became king of the South Saxon kingdom at that time.[7] Then in 686, Cædwalla, now king of Wessex, and his brother Mul, removed Eadric from power and made Mul king of Kent.[lower-alpha 4][6]

[Cædwalla's] hatred and hostility towards the South Saxons were inextinguishable, and he totally destroyed Edric [Eadric] the successor of Ethelwalch [Æthelwealh] who opposed him with renovated boldness:....he also gained repeated victories over the people of Kent..

There is a discussion on the actual date of Eadric's death.[9] Bede lists his death, but does not provide a precise date, however one of the Kent annals, suggest that he was buried on 31 August 686 and another 31 August 687.[9]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The three Kentish law codes are preserved in a twelfth-century law book, the Textus Roffensis (Rochester, Cathedral Library A.3.5)

- ↑ Charter S.8.[5]

- ↑ cum consensu archiepiscopi Theodori et Ędrico . filium fratris mei necnon et omnium principum’[5]

- ↑ Bede HE VI.26 suggests that Mul arrived after Eadric's death.[8]

Citations

- 1 2 Williams 2007, p. 193.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kirby 2000, p. 99.

- 1 2 Stenton 1971, p. 61.

- ↑ Attenborough 1922, pp. 18–23.

- 1 2 Electronic Sawyer 2021.

- 1 2 Yorke 1990, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Welch 1978, p. 32.

- ↑ Story 2005, p. 95 n.129.

- 1 2 Story 2005, p. 83 and p. 83 n.79.

References

- Attenborough, F L (1922). "Hlothere and Eadric". The Laws of the Earliest English Kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780404565459. OCLC 877548400.

- Bede (1910). Lionel C. Jane (ed.). . Vol. III.8. Translated by John Stevens – via Wikisource.

- Electronic Sawyer (2021). "The Electronic Sawyer". London: KCL. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Kirby, D.P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England 3rd edition. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Story, Joanna (2005). "The Frankish Annals of Lindisfarne and Kent". Anglo-Saxon England. 34: 59–109. doi:10.1017/S0263675105000037. hdl:2381/2531. JSTOR 44512356. S2CID 162210483.

- Williams, John H, ed. (2007). The Archaeology of Kent to AD 800. Woodbridge: Boydell Press and Kent County Council. ISBN 978-0-85115-580-7.

- William of Malmesbury (1847). Giles, J.A (ed.). William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 29078478.

- Welch, Martin G. (1978). Brandon, Peter (ed.). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-240-7.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

External links