_-_2022-05-28_-_1.jpg.webp)  Top: Saint-Denis:Bottom: Wells Cathedral | |

| Years active | Mid-12th to mid 13th century |

|---|---|

| Country | France and England |

Early Gothic is a term for the first phase of Gothic style, followed by High Gothic and Late Gothic, dividing the whole Gothic era into three periods. It is defined as a style that used some principle elements of Gothic, but not all. Especially, it had no fine tracery. It marks the first phase of a division of Gothic Style into three periods. If it is used for all countries, it has to be regarded that there may be special terms for the styles of single countries, such as Early English in England.

In France, where Gothic style had been initiated, another phasing has been established:

- Gothique primitif (Primary Gothic) or Gothique premier (First Gothic), from short before 1140 until short after 1180, marked by tribunes above the aisles of basilicas.[1][2]

- Gothique classique (Classic Gothic), from the 1180s to the first third of 13th century, marked by basilicas without lateral tribunes and with triforia without windows. Some buildings of this phase, like Chartres Cathedral, have to be subsumed to Early Gothic, others, like the Reims Cathedral and the western parts of Amiens Cathedral, have to be subsumed to High Gothic.

- Gothique rayonnant (Radiant or Shining Gothic), from the second third of 13th century to the first half of 14th century, marked by triforia with windows and a general preference for stained glass instead of stone walls. It forms the greater portion of High Gothic.

- Gothique flamboyant (Flaming Gothic), since mid 14th century, marked by swinging and flaming (that makes the term) forms of tracery.

The term "Early Gothic" should not be extended backward; if Durham Cathedral and other buildings with the first rib vaults in Romanesque walls are subsumed to this style, most of German Late Romanesque architecture would be Early Gothic.

Primary Gothic appeared in northern France in the 130s. In Normandy, it was mixed with regional traditions. In England, it gave the example for Early English architecture. It combined and developed several key elements from earlier styles, particularly from Romanesque architecture, including the rib vault, flying buttress, and the pointed arch, and used them in innovative ways to create structures, particularly Gothic cathedrals and churches, of exceptional height and grandeur, filled with light from stained glass windows. Notable examples of early Gothic architecture in France include the ambulatory and facade of Saint-Denis Basilica; Sens Cathedral (1140); Laon Cathedral; Senlis Cathedral; (1160) and most famously Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1160).[3]

Early English Gothic was influenced by the French style, particularly in the new choir of Canterbury Cathedral, but soon developed its own particular characteristics, particularly an emphasis for length over height, and more complex and asymmetric floor plans, square rather than rounded east ends, and polychrome decoration, using Purbeck marble. Major examples are the nave and west front of Wells Cathedral, the choir of Lincoln Cathedral, and the early portions of Salisbury Cathedral.[4]

Early Gothic was succeeded in the early 13th century by a new wave of larger and taller buildings, with further technical innovations, in a style later known as High Gothic.[5]

Origins

French Gothic architecture was the result of the emergence in the 12th century of a powerful French state centered in the Île-de-France. King Louis VI of France (1081–1137), had succeeded, after a long struggle, in bringing the barons of northern France under his control, and successfully defended his domain against attacks by the English King, Henry I of England (1100–1135). Under Louis and his successors, cathedrals were the most visible symbol of the unity of the French church and state. During the reign of Louis VI of France (1081–1137), Paris was the principal residence of the Kings of France, the Carolingian era Reims Cathedral the place of coronation, and the Abbey of Saint-Denis became the ceremonial burial place. The King and his successors lavishly supported the construction and enlargement of abbeys and cathedrals.

The Abbot of Saint-Denis, Suger, was not only a prominent religious figure but also first minister to Louis VI and Louis VII. He oversaw the royal administration when the King was absent on the Crusades. He commissioned the reconstruction of the Basilica of Saint-Denis, making it the first and most influential example of the new style in France.[6]

Basilica of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis was important because it was the burial place of the French Kings of the Capetian dynasty from the late 10th until the early 14th century. It attracted a very large number of pilgrims, attracted by the relics of Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris. To accommodate the large number of pilgrims, Suger first constructed a new narthex and facade at the west end, with twin towers and a rose window in the center.

The most original and influential step made by Suger was the creation of the chevet, or east end, with radiating chapels. Here he used the pointed arch and rib vault in a new way, replacing the thick dividing walls with arched rib vaults poised on columns with sculpted capitals. Suger wrote that the new chevet was "ennobled by the beauty of length and width." And "the midst of the edifice was suddenly raised aloft by twelve columns". He added that, when creating this feature, he was inspired by the ancient Roman columns he had seen in the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian and elsewhere in Rome.[7] He described the finished work as "a circular string of chapels, by virtue of which the whole church would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty."[8]

Suger was an admirer of the doctrines of the early Christian philosopher John Scotus Eriugena (c. 810–87) and Dionysus, or the Pseudo-Areopagite, who taught that light was a divine manifestation, and that all things were "material lights", reflecting the infinite light of God himself.[8] Therefore, stained glass became a way to create a glowing, unworldly light ideal for religious reflection.[3]

According to Suger, every aspect of the new apse architecture had a symbolic meaning. The twelve columns separating the chapels, he wrote, represented the twelve Apostles, while the twelve columns of the side aisles represented the minor prophets of the Old Testament.[7]

The Basilica, including the upper parts of the choir and the apse, were extensively modified into the Rayonnant style in the 1230s, but the original early Gothic ambulatory and chapels can still be seen.[9]

Ambulatory of the Basilica of Saint-Denis

Ambulatory of the Basilica of Saint-Denis Basilica of Saint Denis, west facade (1135–40)

Basilica of Saint Denis, west facade (1135–40) Facade and portals of Basilica of Saint-Denis

Facade and portals of Basilica of Saint-Denis

Early French Gothic cathedrals

Sens Cathedral

The construction of the choir and ambulatory of Sens Cathedral began before the construction of the ambulatory of Saint-Denis. Therefore, the ambulatory is rather Romanesque than Gothic. All adjacent chapels are much later and no more Primary Gothic. But its arcades and triforia already fit the criteria of Gothic architecture.[8] It was constructed between 1135 and 1164. Different from the other cathedrals of Primary Gothic, it has no tribunes above the aisles, but triforia as one of three levels, alike some Romanesque basilicas before and Classic Gothic afterwards. It used the new six-part rib vault in the nave, giving the church exceptional width and height. Because the six-part vaults distributed the weight unevenly, the vaults were supported by alternating massive square piers and more slender round columns.[10][11][12] It had a wide impact on the Gothic style not only in France, but also in England, because its master builder, William of Sens, was invited to England and introduced Early Gothic features to the reconstructed quire of Canterbury Cathedral.

In the following centuries, all clerestories were remodelled, and the transept is Flamboyant.

Facade of Sens Cathedral (1135–64)

Facade of Sens Cathedral (1135–64).jpg.webp) Elevation of Sens Cathedral: three levels; the tribune above the aisle, typical for Primary Gothic, is still missing.

Elevation of Sens Cathedral: three levels; the tribune above the aisle, typical for Primary Gothic, is still missing. Radiating chapels of Sens Cathedral

Radiating chapels of Sens Cathedral

Senlis Cathedral

Senlis Cathedral was built between 1153 and 1191. Its length was limited by modest budget and by the placement of the building against the city wall. Like Sens cathedral, it was composed of a nave without a transept, flanked by a single collateral. The radiating chapels of the choir are separate extensions of the ambulatory (different from Saint-Denis, whree thy form something like an outer aisle). They gave an example for Magdeburg Cathedral that was begun in 1209 and has polygonal ambulatory and chapels. The elevation of Senlis originally had four levels, including large tribunes. Like Sens, Senlis Cathedral had alternating strong and weak piers to receive the uneven thrust from the six-part rib vaults. The church underwent considerable rebuilding in the 13th and 16th century, including a new tower and new interior decorations. Many of the early Gothic features are overladen with Flamboyant and later decoration.[13] In the 16th century, the triforia disappeared, whereas the tribunes kept their Primary Gothic layout until today.

Nave: arcades and tribunes 1153–91

Nave: arcades and tribunes 1153–91%252C_cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame%252C_chapelle_Sainte-Genevi%C3%A8ve%252C_chapiteaux_au_nord_du_doubleau_interm%C3%A9diaire_1.jpg.webp) Sculpted capitals of the piers, Chapel of Sainte-Genevieve

Sculpted capitals of the piers, Chapel of Sainte-Genevieve%252C_cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame%252C_ch%C5%93ur%252C_parties_hautes%252C_vue_depuis_le_sud-est_2.JPG.webp) Buttresses of Primary Gothic, Flamboyant clerestory of C XVI

Buttresses of Primary Gothic, Flamboyant clerestory of C XVI

Noyon Cathedral

Noyon Cathedral, begun between 1150 and 1155, was the first of a series of famous Cathedrals to appear in Picardy, the prosperous region north of Paris. The city an important connection with French history, as the coronation site of Charlamagne and of the early French King Hugh Capet. The new cathedral still had many Romanesque features, including prominent transepts with rounded ends and deep galleries, but it introduced several Gothic innovations, including the fourth level, the triforium a narrow passageway between the ground-level gallery, the tribunes, and the top level clerestory, Noyon also used massive compound piers alternating with round columns, necessary because of the uneven weight distribution from the six-part vaults.[8] The east end has five radiating chapels and three levels of windows, creating a created a dramatic flood of light into the nave.[14]

- Noyon Cathedral

Choir, begun short after 1150, elevation with 4 levels: arcade, tribune, triforium, clerestory

Choir, begun short after 1150, elevation with 4 levels: arcade, tribune, triforium, clerestory%252C_cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame%252C_bas-c%C3%B4t%C3%A9_nord%252C_vue_diagonale_vers_le_sud-ouest_par_la_6e_et_5e_grande_arcade.jpg.webp) The alternating piers and columns of the grand arcade, which support the vaults

The alternating piers and columns of the grand arcade, which support the vaults Façade, 1200–1235, Classic Gothic

Façade, 1200–1235, Classic Gothic

Laon Cathedral

Laon Cathedral was begun in 1155, in Primary Gothic style. until about 1180, the (first) choir, crossing and transept and the eastern five bays of the nave were finished. The western part of the nave and the façade followed until 1200. Therefore, the façade is already an example of Classic Gothic; Villard de Honnecourt praised the innovative upper parts of the towers. But the original choir began to decay and in 1205–1220 was replaced by the actual one. Following English examples, it has no apse, but a rectangular east end.

Laon was built upon a hilltop one hundred meters high, making it visible from a great distance. The hilltop imposed a special burden for the builders; all the stones had to be carried to the top of the hill in carts drawn by oxen. The oxen who did the work were honored by statues on the tower of the finished cathedral.[13]

Laon was also unusual because of its five towers; two on the west front, two on the transepts, and an octagonal lantern on crossing. Laon, like most early Gothic cathedrals, had four interior levels. Laon also had alternating octagonal and square piers supporting the nave, but these rested upon massive pillars made of dreamlike sections of stone, giving it greater harmony and a greater sensation of length.[15] The new cathedral was unusual in form; The apse on the east was flat, not rounded, and The choir was exceptionally long, nearly as long as the nave.[16] Another striking feature of Laon Cathedral were the three great rose windows, one on the west facade and two on the transepts. (Only the west and north windows still remain). Another unusual feature at Laon is lantern tower at the transept crossing, most likely inspired by the Norman Gothic abbey churches in Caen.[13]

Laon Cathedral gave the example for the first Gothic project in Germany, the Gothic remodeling of Limburg Cathedral, begun in the 1180s.[17][18]

- Laon Cathedral

Eastern part of the nave (before 1180), towards the choir, replaced in 1205–1220.

Eastern part of the nave (before 1180), towards the choir, replaced in 1205–1220. Façade (1180–1200)

Façade (1180–1200) "English" footplan

"English" footplan

Notre Dame de Paris

Notre Dame de Paris was the largest of the Early Gothic cathedrals, and marked the summit of the Early Gothic in France. It was begun in 1163 by the Bishop Maurice de Sully with the intention of surpassing all other existing churches in Europe. The new cathedral was 122 meters long and 35 meters high, eleven meters higher than Laon Cathedral, the previous tallest church. It featured a central nave flanked by double collaterals, and a choir surrounded by a double ambulatory, without radiating chapels. (The current chapels were added between the buttresses in the 14th century).[19]

The builders covered the interior of the cathedral with six-part vaults, but unlike Sens and other the earlier cathedrals they did not use alternating piers and columns to support them. The vaults were supported instead by bundles of three uninterrupted slender columns which were received by rows massive pillars with capitals decorated with classical decoration. This gave the nave greater harmony.

The upper parts of the choir were built at about 1182 or 1185, not long before Chartres Cathedral. Its original elevations were intermediate between tree levels and four levels: above the tribunes there were no veritable triforia, but a clerestory with two levels of windows, the lower level consisted of small rose windows, and the upper level of modest pointed arched windows without tracery.

In the 13th century, when it was decided that the interior was too dark, and the upright windows were enlarged downward into the area of the small roses. Around the transept, the original design was reconstructed during the restoration by Viollet-le-Duc.[19]

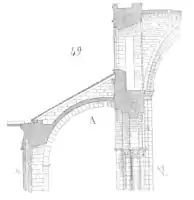

The flying buttress made its first appearance in Paris in the early 13th century, either at Notre Dame, or perhaps earlier in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres. The buttresses, in the form of half-arches, reached from the heavy buttresses outside the nave, over the top of the tribunes, and pressed directly against the upper walls of the nave, countering the outward thrust from the vaults. This made possible the installation of larger windows in the upper walls of the nave the buttresses.[19]

- Notre Dame de Paris

Reconstructed Primary Gothic clerestories adjacent to the northern transept.

Reconstructed Primary Gothic clerestories adjacent to the northern transept. Nave looking to the east: six-part rib vaults, clerestories remodeled after 1220, three levels only.

Nave looking to the east: six-part rib vaults, clerestories remodeled after 1220, three levels only. West façade: rose level built at about 1220.

West façade: rose level built at about 1220. The flying buttresses of Notre Dame as they appeared in about 1220–30 (drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc)

The flying buttresses of Notre Dame as they appeared in about 1220–30 (drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc)

Chartres Cathedral (1194–1225)

Chartres Cathedral was the site of four annual trade fairs on the Feast Days of the Virgin Mary and a popular pilgrimage site that displayed the reputed tunic that Mary wore when giving birth to Christ.[20] A series of earlier cathedrals in Chartres beginning in the fourth century, were destroyed by fire. The cathedral immediately previous to the present church burned in 1194, leaving only the crypt, towers, and the recently built west front. Rebuilding began the same year, with support from the Pope, the King, and the wealthy nobility and merchants of the city.

Concerning its windows (without tracery or with plate tracery), this cathedral was still an example of Early Gothic, but its elevations were innovative. Therefore Chartres Cathedral is considered the initial building of Classic Gothic. The arcades and aisles were much taller than in the first Gothic cathedrals, and the tribune were omitted. Also the clerestories were higher than in any basilica before it. Except for their lowest parts, the apse and the chapels were polygonal.

Work was nearly completed by 1225, with the architecture, glass and sculpture finished, though the seven steeples were still being rebuilt. It was not formally reconsecrated until 1260. Only a few changes were made since that time, including the addition of a new chapel dedicated to Saint Piat in 1326, and the covering of the choir columns with stucco and the addition of marble reliefs in behind the stalls in the 1750s.[21]

The new cathedral was 130.2 meters long and 30 meters high in the nave longer and higher than Notre-Dame de Paris.[22] Since the cathedral was constructed with the new flying buttresses, the walls were more stable, enabling the builders to eliminate the tribune level, and have more space for windows.[22]

The lower portions of the west front (1134–1150) are Early Gothic. The north and south transepts fronts are High Gothic, as is the sculpture of the six thirteenth-century portals. The spire on the north tower is later Flamboyant.[20] Chartres still has much of its original medieval stained glass, famous for the deep color called Chartres blue.[20]

- Chartres Cathedral

The choir and the apse chapels of Chartres Cathedral, except for the crypts already polygonal

The choir and the apse chapels of Chartres Cathedral, except for the crypts already polygonal South side of the nave: No fine tracery, except for the Flamboyant window on the very right

South side of the nave: No fine tracery, except for the Flamboyant window on the very right

Bourges Cathedral (1195–1230)

While most High Gothic cathedrals generally followed the Chartres plan, Bourges Cathedral took a different direction. It was built by Bishop Henri de Sully, whose brother, Eudes de Sully, was the bishop of Paris, and its construction in several ways followed Notre-Dame de Paris and not Chartres. Like Chartres, the builders simplified the vertical plan to three levels; grand arcades, triforium, and high windows. The triforium was simplified a long horizontal band, the entire length of the church. However, unlike Paris, Bourges continued to use the older six-part rib vault used in Paris. This meant that the weight of the vaults fell unevenly upon the nave, and required, like Early Gothic cathedrals, alternating strong and weak pillars. This was artfully hidden by the use of large cylindrical piers, each surrounded by eight engaged colonettes. The piers of the arcade are particularly imposing; each is 21 m (69 ft) tall.[23] Choir and chapels of Bourges cathedral still have semicircular ends.

Since Bourges used six-part rib vaults instead of the lighter four-part vaults, the upper walls had to resist greater outward thrust, and the flying buttresses had to be more effective. The Bourges buttresses used a unique design with a particularly acute angle, which gave it the necessary force, but it was also reinforced by thicker and stronger walls than Chartres.[23]

The predominant sensation at Bourges is not only great height, but great length and interior space; the cathedral is 120 m (390 ft) long, without a transept or other interruption.[24] The most unusual feature of Bourges Cathedral is the arrangement of vertical height; each part of the elevation is set back, like steps, with the highest roof and vaults over the central aisle. The outermost aisles have vaults nine meters high; the intermediate aisles have vaults 21.3 m (70 ft) high; and the center aisle has vaults 37.5 m (123 ft) high.[23]

Many later Gothic cathedrals followed the Chartres model, but several were influenced by Bourges, including Le Mans Cathedral, the modified Beauvais Cathedral, and Toledo Cathedral in Spain, which copied the system of vaults of different heights.[23]

- Bourges Cathedral

Nave, with 21-meter-high piers of the grand arcades

Nave, with 21-meter-high piers of the grand arcades The chevet, all windows without tracery.

The chevet, all windows without tracery.

Angevin Gothic

Most buildings of Plantagenet style, also called Angevin Gothic, by dating and by shape are part of early Gothic. In the reconstruction of Angers Cathedral begun by bishop Normand de Doué, 1148–1152, the first Angevin vault were constructed. Poitiers Cathedral, erected since 1166 is known as the first Gothic hall church. Its eastern parts are Early Gothic with som Romanesque elements, ist western Parts have High Gothic trecery.

Early Classic Gothic

Some crucial examples of Classic Gothic, such as Chartres Cathedral (see above) and Bourges Cathedral fit the criteria of Early Gothic.

Early Gothic in Normandy

Experiments with Gothic features were also underway in Normandy in the late 11th and 12th centuries. In 1098 Lessay Abbey was given an early version of the pointed rib vault in the choir.[25] The church of Saint-Pierre de Lisieux, begun in the 1170s, featured the more modern four-part rib vaults and flying buttresses. Other experiments with Gothic rib vaults and other features took place in Caen, in the churches of the two large royal abbeys churches, the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen and the Abbey of Sainte-Trinité, Caen, but they remained essentially Norman Romanesque churches.[26]

Rouen Cathedral had notable early Gothic features, added when the interior was reconstructed from Romanesque to Gothic by archbishop Gautier de Coutances beginning in 1185. The new Gothic nave was given four levels, while the later choir had the newly fashionable three.[26]

Early Gothic in England

Canterbury Cathedral

One of the first major buildings in England to use the new style was Canterbury Cathedral. A fire destroyed the mainly Romanesque choir in September 1174, and leading architects from England and France were invited to offer plans for its reconstruction. The winner of this competition was a French master builder, William of Sens, who had been involved in the construction of Sens Cathedral, the first complete Gothic cathedral in France. [27]

Many limitations were put upon William of Sens by the monks who ran the cathedral. He was not allowed to replace entirely the original Norman church, and had to fit his new structure on the old crypt and within the surviving outer Norman walls. Nonetheless, he achieved a strikingly original sculpture, showing elements inspired by Notre-Dame de Paris and Laon Cathedral. Following the French model, he used six-part rib vaults, pointed arches, supporting columns with carved acanthus leaf decoration, and a semi-circular ambulatory. However, other elements were purely English, such as the use of dark Purbeck marble to create decorative contrasts with the pale stone brought from Normandy. The work was described by a monk and chronicler, Gervase of Canterbury. Contrasting the old with the new choir. He wrote: "There, the arches and everything else was plain, or sculpted with an axe and not with a chisel. But here almost throughout is appropriate sculpture. There used to be no marble shafts, but here are innumerable ones. There in the circuit round the choir, the vaults were plain, but here they are arch-ribbed and have key-stones." [28]

William of Sens fell from a scaffolding in 1178 and was seriously injured, and returned to France, where he died,[29] and his work was continued by an English architect, William the Englishman, who constructed the Trinity Chapel in the apse and the Corona in the east end, which were monuments to Thomas Becket, who had been murdered in the cathedral. The new structure had many French features, such as the doubled columns in the Trinity chapel, and piers replaced by Purbeck-marble wall shafts. But it also retained many specifically English features, such as a great variety in the level and placement of the spaces; the Trinity chapel, for example is sixteen steps above the Choir). It also retaining rather than eliminated the transepts - Canterbury had two. Early English Gothic put an emphasis on great length; Canterbury was doubled in length between 1096 and 1130.[28]

One reason for the differences between French and English Gothic was that French Benedictine abbey-churches usually put different functions into separate buildings, while in England they were usually combined in the same structure. Similar complicated multifunctional designs were found not only in Canterbury, but in the abbey-churches of Bath, Coventry, Durham, Ely, Norwich, Rochester, Winchester and Worcester.[30]

.jpg.webp) Choir of Canterbury Cathedral rebuilt by William of Sens (1174–1184)

Choir of Canterbury Cathedral rebuilt by William of Sens (1174–1184) The windows and vaults of Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral

The windows and vaults of Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral

The Cistercian abbeys

Another notable form of early English Gothic architecture was that of the Cistercian monasteries. The Cistercian order had been formed in 1098 as a reaction against the opulence and ornament of the Benedictine order and its monasteries. The architecture of the Cistercians was based upon simplicity and functionality. All decoration was forbidden. The Cistercian monasteries were in remote locations, far from the cities. They were closed in 1539 during the reign of Henry VIII, and now are picturesque ruins. Examples include Kirkstall Abbey (c. 1152); Roche Abbey (c. 1172), and Fountains Abbey (c. 1132) all in Yorkshire.

Kirkstall Abbey (c. 1152)

Kirkstall Abbey (c. 1152) Roche Abbey (c. 1172)

Roche Abbey (c. 1172) Fountains Abbey (c. 1132)

Fountains Abbey (c. 1132)

Wells Cathedral

Wells Cathedral, (built between 1185–1200 and modified until 1240) is another leading example of the early English style. It borrowed some aspects, such as its elevation, from the French style, but gave precedence to strong horizontals, such as the triforium, rather than the dominant vertical elements, such as wall shafts, of the French style. The piers were composed of as many as twenty-four shafts, adding another unusual decorative effect.[31] The north porch, built in 1210–15, and especially the west front (1220–1240) had a particularly novel decorative effect. The screen facade of the west front is filled with nearly four hundred carved and painted stone figure, and is made more impressive by two flanking towers, attached to but not part of the body of the church. This arrangement was adapted by other English cathedrals, including Salisbury Cathedral and Exeter Cathedral.[31]

West front of Wells Cathedral (1220–1240)

West front of Wells Cathedral (1220–1240) Nave of Wells Cathedral, with its strong horizontal emphasis. The unusual double arch was added in 1338 to reinforce the support of the tower.

Nave of Wells Cathedral, with its strong horizontal emphasis. The unusual double arch was added in 1338 to reinforce the support of the tower. Detail of the sculpted capitals of clustered columns in the nave

Detail of the sculpted capitals of clustered columns in the nave

Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1260) is another example of the mature Early English Gothic. Salisbury is best known for its famous crossing tower and spire, added in the 14th century, but its complex plan, with two sets of transepts, a projecting north porch and a rectangular east end, is a classic example of the early English Gothic.[32] It was a distinct contrast from the French Amiens Cathedral, begun the same year, with its simple apse on east and its minimal transepts. The nave has strong horizontal lines created by the contrast of the dark Purbeck marble columns. The Lady Chapel of Salisbury has extremely slender pillars of Purbeck marble supporting the vaults, shows the diversity and harmony of mature English Early Gothic, entering the period of Decorated Gothic.[32]

The sprawling plan of Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1260), with its multiple transepts and projecting porch

The sprawling plan of Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1260), with its multiple transepts and projecting porch The nave of Salisbury Cathedral, with its strong horizontal lines of dark Purbeck marble columns

The nave of Salisbury Cathedral, with its strong horizontal lines of dark Purbeck marble columns The choir of Salisbury Cathedral

The choir of Salisbury Cathedral The Lady Chapel of Salisbury Cathedral

The Lady Chapel of Salisbury Cathedral

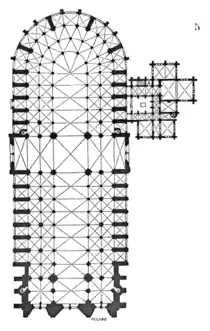

Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral (rebuilt from the Norman style beginning in 1192), is the best example of the fully mature early Gothic style.[4] The master-builder, Geoffrey de Noiers, was French, but he constructed a church with distinct non-French features; double transepts, an elongated nave, complexity of interior space, and a more lavish use of decorative features.[31] St. Hugh's Choir, named after the French-born monk St. Hugh of Lincoln, was a good example. The choir was covered with a rib vault in which most of the ribs had a purely decorative role. In addition to the functional ribs, it featured extra ribs called tiercerons, which did not lead to the central point of the vault, but to a point along the ridge rib on the crown of the vault. They were put together in lavish designs, which gave the resulting ceiling the nickname "The crazy vault."[31]

Another distinctive English element introduced at Lincoln was the use of s the blind arcade (also known as a blank arcade) in the decoration of Hugh's chapel. Two layers of arcades with pointed arches are attached to the walls, giving a theatrical effect of three dimensions. This element is enhanced by the use of different color stone for the thin columns; ribs of white limestone for the lower columns and black Purbeck marble for the upper portions.[31]

A third feature important feature of Lincoln was the thick or double-shell wall. This was an Anglo-Romanesque feature, which earlier had been in used in Romanesque structures of Caen, and in Durham and Winchester Cathedral. Instead of being supported only by flying buttresses, the vaults receive additional support from the thicker walls of the gallery over the aisles. This allowed a considerably wider span across the nave, and also meant that the vaults could have additional purely decorative ribs, as in the "Crazy vault".[33]

Lincoln Cathedral (rebuilt beginning in 1192)

Lincoln Cathedral (rebuilt beginning in 1192) The wide nave of Lincoln Cathedral

The wide nave of Lincoln Cathedral The "Crazy Vaults" of the St. Hugh's choir of Lincoln Cathedral

The "Crazy Vaults" of the St. Hugh's choir of Lincoln Cathedral Blind arcades of St. Hugh's choir in Lincoln Cathedral

Blind arcades of St. Hugh's choir in Lincoln Cathedral

Characteristics

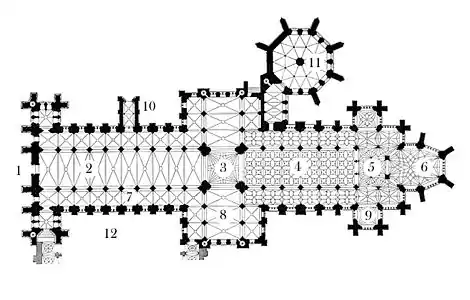

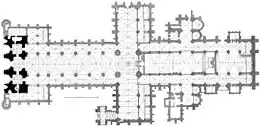

Plans

The plans of the early Gothic cathedrals in France were usually in the form of a Greek cross, and were relatively simple. Sens Cathedral, the first in France, was a good example; A facade with three portals and two towers; a long nave with collateral aisles; a rather long choir, a very short transept, and a rounded apse with a double ambulatory and radiating chapels. Variations on this plan were used in most early French cathedrals, including Noyon Cathedral and Notre Dame de Paris.[34]

Choir and ambulatory of Saint-Denis abbey church, 1140

Choir and ambulatory of Saint-Denis abbey church, 1140 Plan of Sens Cathedral begun in 1135

Plan of Sens Cathedral begun in 1135 Noyon Cathedral, 1130–1150, plan without later additions

Noyon Cathedral, 1130–1150, plan without later additions Notre Dame de Paris, begun in 1163, plan with additions since 1220.

Notre Dame de Paris, begun in 1163, plan with additions since 1220. Choir and ambulatory of Notre Dame de Paris before 1220, reconstruction by Violet-le-Duc

Choir and ambulatory of Notre Dame de Paris before 1220, reconstruction by Violet-le-Duc

The plans of the early English Gothic cathedrals were usually longer and much more complex, with additional transepts, attached chapels, external towers, and usually a rectangular west end. The choirs were often as long as the nave. The form expressed the multiple activities often going on simultaneously in the same building.[35]

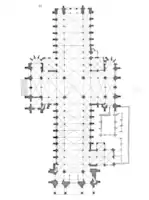

Plan of Wells Cathedral (begun 1175)

Plan of Wells Cathedral (begun 1175) Plan of Lincoln Cathedral (begun 1192)

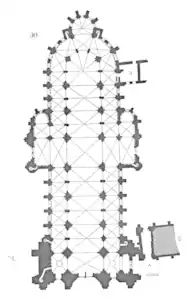

Plan of Lincoln Cathedral (begun 1192) Salisbury Cathedral (begun 1220)

Salisbury Cathedral (begun 1220)

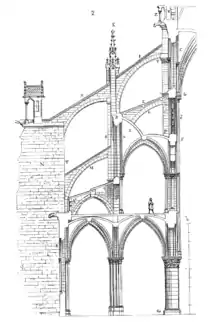

Elevations

At the time of the early Gothic, the flying buttress was not yet in common use, and buttresses were placed directly close to or directly against the walls. The walls had to be reinforced by additional width.[36] The early Gothic churches in France typically had four elevations or levels in the nave: the aisle arcade on the ground floor; the gallery arcade, a passageway, above it; the blind triforium, a narrower passageway, and the clerestory, a wall with larger windows, just under the vaults. These multiple levels added to the width and thus the stability of the walls, before the flying buttress was commonly used. This was the system used at Sens Cathedral, Noyon Cathedral and originally at Notre Dame de Paris.[36]

The introduction of a simpler four-part rib vault and especially the flying buttress meant that the walls could be thinner and higher, with more room for windows. By the end of the period, the triforium level was usually eliminated, and larger windows filled the space.[36]

Noyon Cathedral, late 12h century, four levels: arcade, tribune, triforium, clerestory

Noyon Cathedral, late 12h century, four levels: arcade, tribune, triforium, clerestory Choir of Notre Dame de Paris, consecration 1182, three levels (arcade, tribune and clerestory); triforia removed by the remodeling of the clerestories after 1220

Choir of Notre Dame de Paris, consecration 1182, three levels (arcade, tribune and clerestory); triforia removed by the remodeling of the clerestories after 1220 Three-part elevation of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176)

Three-part elevation of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176) Nave of Lincoln Cathedral. showing three levels; arcades (bottom); tribunes {middle} and clerestory (top).

Nave of Lincoln Cathedral. showing three levels; arcades (bottom); tribunes {middle} and clerestory (top).

Vaults

The rib vault was a characteristic feature of Gothic architecture from the beginning. It was the result of a search for a way to build stone roofs on churches that could not catch fire but would not be too heavy. Variations of rib vaults had been used in Islamic and Romanesque architecture, often to support domes.[37] The rib vault had thin stone ribs which carried the vaulted surface of thin panels.[9] Unlike the earlier barrel vault, where the weight of the vault pressed down directly onto the walls, the arched ribs of a rib vault had a pointed arch, a rib which directed the weight outwards and downwards to specific points, usually piers and columns in the nave below, or outward to the walls, where it was countered by buttresses. The panels between the ribs were made of small pieces of stone, and were much lighter than the earlier barrel vaults. A primitive form, a ribbed groin vault, with round arches, was used at Durham Cathedral, and then, in the course of building, was improved with pointed arches in about 1096. Other variations had been used at Lessay Abbey in Normandy at about the same time.[35]

The first Gothic rib vaults were divided by the ribs into six compartments. A six-part vault could cover two sections of the nave. Two pointed arches crossed diagonally and were supported by an intermediate arch, which crossed the nave from side to side. The weight was carried downward by thin columns from the corners of the vault to the alternating heavy piers and thinner columns in the nave below. The weight was distributed unevenly; the piers received the greater weight from diagonal arches, while the columns took the lesser weight from the intermediate arch. This system was used successfully at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, Noyon Cathedral, Laon Cathedral, and Notre-Dame de Paris.

A simpler and stronger vault with just four compartments was developed at the end of the period by eliminating the intermediate arch. As a result, the piers or columns below all received an equal load, and could have the same size and appearance, giving greater harmony to the nave. This system was used increasingly at the end of the Early Gothic period.

More elaborate rib vaults were introduced in England later in the period, at Lincoln Cathedral. These had additional purely decorative ribs called the lierne and the tierceron, in ornate designs like stars and fans, They were the work of Geoffrey de Noiers, a French or French-Normand master-builder who between 1192 and 1200 designed St. Hugh's choir, completed in 1208. The ribs were designed so that the bays slightly offset each other, giving them the nickname of "Crazy vaults".[38] De Noiers was succeeded at Lincoln by Alexander the Mason, who designed the tierceron star vaulting in the cathedral's nave.[39] at Lincoln Cathedral.[40]

Six-part vaults in Sens Cathedral (begun 1135)

Six-part vaults in Sens Cathedral (begun 1135) Six-part rib vaults in Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1163)

Six-part rib vaults in Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1163) Four-part vaults of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176)

Four-part vaults of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176) "Crazy vaults" of Lincoln Cathedral in St. Hugh's choir (1192–1208)

"Crazy vaults" of Lincoln Cathedral in St. Hugh's choir (1192–1208)

Flying buttress

Variations of the flying buttress existed before the Gothic period, but Gothic architects developed them to a high degree of sophistication. By counterbalancing the thrust against the upper walls from the rib vaults, they made possible the great height, thin walls and large upper windows of the Gothic cathedrals. The early Gothic buttresses were placed close to the walls, and were columns of stone with a short arch to the upper level, between the windows. They were often topped by stone pinnacles both for decoration, and to make them even heavier.

Flying buttress at the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen, Caen (11th century)

Flying buttress at the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen, Caen (11th century) Early buttresses of Noyon Cathedral

Early buttresses of Noyon Cathedral Buttresses of Laon Cathedral

Buttresses of Laon Cathedral Flying buttresses of Salisbury Cathedral

Flying buttresses of Salisbury Cathedral

Sculpture

The most important sculptural decoration of early Gothic cathedrals was found over and around the portals, or doorways, on the tympanum and sometimes also on the columns. Following the model of Romanesque churches, these depicted the Holy Family and Saints. Following the tradition of Romanesque sculpture, the figures were usually stiff, straight, simple forms, and often elongated. As the period advanced, the sculpture became more naturalistic. The floral and vegetal sculpture of the capitals of columns in the nave was more realistic, showing a close observation of nature.[4]

One of the finest examples of early Gothic sculpture is the tympanum over the royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245), which survived a fire that destroyed much of the early Cathedral.

Central tympanum of the royal portal, Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245)

Central tympanum of the royal portal, Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245).jpg.webp) Detail of the royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245)

Detail of the royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245) Adam and Eve eating apples, west front of Lincoln Cathedral (12th century)

Adam and Eve eating apples, west front of Lincoln Cathedral (12th century)

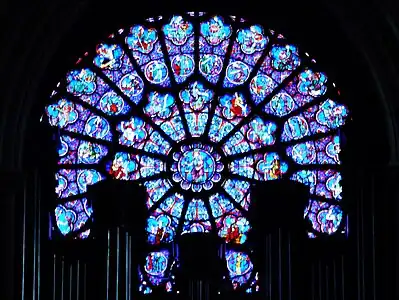

Stained glass

Stained glass had existed for centuries, and was used in Romanesque churches, but it became was a particularly important feature of early Gothic architecture. The Abbot Suger commissioned stained glass windows for the Basilica of Saint-Denis to fill the ambulatory and chapels with what he considered to be divine light. The stained glass windows of Saint-Denis and other Early Gothic churches had a particular intensity of color, partly because the glass was thicker and used more color, and partly because the early windows were small, and their light had a more striking contrast with the dark interiors of the churches and cathedrals.

The process of making the windows was described by the monk Theophilus Presbyter in the early 12th century. The glass and the windows were made by different craftsmen, usually at different locations. The molten glass was coloured with metal oxides; cobalt for blue, copper for red, iron for green, manganese for purple and antimony for yellow. When molten, it was blown into a bubble, formed into a tubular shape, cut at the ends to make a cylinder, then slit and flattened while it was still hot. It ranged in thickness from 3 to 8 mm (0.12 to 0.31 in). A full-size drawing of the window was made on a large table, and then pieces of colored glass were "grozed", or cracked off the sheet, and assembled on the table. The details of the windows were then painted on in vitreous enamel, then fired. The glass pieces were fit into grooved pieces of lead, which were soldered together, and sealed with putty to make them waterproof, to complete the window.[41][42]

The rose window was a particular feature of early Gothic. They had been used in Romanesque architecture, such as the two small windows on the facade of Pomposa Abbey in Italy (early 10th century), but they became more important and complex in the Gothic period. In the 12th century, according to Bernard of Clairvaux, writing at that time, the rose was the symbol of the Virgin Mary, and had a prominent place on the facades of the cathedrals named for her, such as Notre-Dame de Paris, whose west rose window dates from 1220.[43]

The rose windows of the Early Gothic churches were composed of plate tracery, a geometric pattern of openings in stone over the central portal. Early examples included the rose on the west facade of the Basilica of Saint-Denis (though the present window is not original), and the early rose window on the west front of Chartres Cathedral. Other examples are the rose on the west front of Laon Cathedral and Notre Dame de Mantes (1210) [43] York Minster has what is believed to be the oldest existing stained glass window in England, a Tree of Jesse (1170).

12th century stained glass from Basilica of Saint-Denis

12th century stained glass from Basilica of Saint-Denis Detail of a Tree of Jesse from York Minster (c. 1170), the oldest stained-glass window in England.

Detail of a Tree of Jesse from York Minster (c. 1170), the oldest stained-glass window in England. Rose window of Notre Dame de Mantes (c. 1210)

Rose window of Notre Dame de Mantes (c. 1210) West rose window of Notre Dame de Paris (c. 1220)

West rose window of Notre Dame de Paris (c. 1220)

See also

References

- ↑ "L'Histoire, L'art gothique à la conquête de l'Europe". Archived from the original on 2023-05-06. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ↑ "Dominiqque Vermand, portal Églises de l'Oise → article Noyon, cathédrale Notre-Dame (→ section Chronologie)". Archived from the original on 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- 1 2 Watkin 1986, p. 126–128.

- 1 2 3 Gothic art at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 33.

- 1 2 Watkin 1986, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 Watkin 1986, p. 128.

- 1 2 Western architecture at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Mignon 2015, p. 10-11.

- ↑ Le Guide du Patrimoine de France (2002) pg. 53

- ↑ Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 33–35.

- 1 2 3 Mignon 2015, p. 16–17.

- ↑ Mignon 2015, p. 14.

- ↑ Watkin 1986, p. 129.

- ↑ Mignon 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Matthias Theodor Kloft, Dom und Domschatz in Limburg an der Lahn, puublshed by Verlag Langewiesche, Königstein im Taunus 2016 (= Die Blauen Bücher), ISBN 978-3-7845-4826-5.

- ↑ Matthias Theodor Kloft, Limburg an der Lahn – Der Dom, published by Verlag Schnell und Steiner, 19th revised edition, 2015, ISBN 978-3-7954-4365-8

- 1 2 3 Mignon 2015, p. 18–19.

- 1 2 3 Watkin 1986, p. 131.

- ↑ Houvet 2019, p. 12.

- 1 2 Mignon 2015, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 Bony 1985, p. 212.

- ↑ Mignon 2015, p. 24.

- ↑ Encyclopédie Larousse on-line, "Le Premier Art Gothique" (retrieved May 3, 2020

- 1 2 Mignon 2015, p. 30–31.

- ↑ Watkin 1986, p. 143.

- 1 2 Watkin 1986, p. 143–144.

- ↑ "As work began on the vault of the eastern part of the choir, William was incapacitated by a fall from a scaffold. He probably continued to direct the work from his sickbed, but this was impractical, and so he gave up and returned to France, where he died." William of Sens at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Watkin 1986, p. 144–145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Watkin 1986, p. 145.

- 1 2 Watkin 1986, p. 147.

- ↑ Watkin 1986, p. 146.

- ↑ Ducher 2014, pp. 40–43.

- 1 2 Gothic architecture at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1 2 3 Ducher 2014, p. 42.

- ↑ Watkin 1986, p. 126–127.

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2016). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-19-967499-2.

- ↑ Acland, James H. (1972). Medieval Structure: The Gothic Vault. University of Toronto Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-8020-1886-6.

- ↑ Ducher 2014, p. 54.

- ↑ stained glass at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters. "Stained Glass in Medieval Europe Archived 2021-11-22 at the Wayback Machine". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1 2 Trintignac & Coloni 1984, p. 44–45.

Bibliography

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.

- Rivière, Rémi; Lavoye, Agnès (2007). La Tour Jean sans Peur, Association des Amis de la tour Jean sans Peur. ISBN 978-2-95164-940-8

- Trintignac, André; Coloni, Marie-Jeanne (1984). Decouvrir Notre-Dame de Paris (in French). Paris: Cerf. ISBN 2-204-02087-7.

- Texier, Simon, (2012), Paris Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours, Parigramme, Paris (in French), ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Cothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (2002), Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux (in French) ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0

.jpg.webp)