Ebenezer Eastman | |

|---|---|

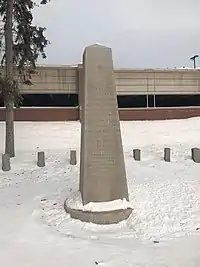

Obelisk honoring Captain Eastman in Concord, New Hampshire | |

| Born | February 17, 1681 Haverhill, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British America |

| Died | July 28, 1748 (aged 67) Concord, Province of New Hampshire, British America |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) |

Sarah Peasley (m. 1710) |

| Children |

|

Ebenezer Eastman (February 17, 1681 - July 28, 1748) was a naval captain and supposed founding figure of Concord, New Hampshire. Born in Haverhill, Massachusetts, to a veteran of King Philip's War, Eastman participated in various military conflicts in Canada throughout his career as a captain in the Royal Navy. Thoroughly involved in Concord's affairs, he established himself as a respected member of the town, at the time called Rumford. He is recorded as being the "strong man" of the now-capital.[3]

Ancestry

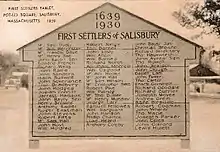

Ebenezer Eastman's paternal grandfather, Roger Eastman (c. April 4, 1610 - December 16, 1694), was born in Wiltshire, England[4] and arrived in Salisbury, Massachusetts, in 1638 aboard the ship Confidence as an indentured servant of John Saunders.[5] He married a woman named Sarah, with whom he had ten children. Roger worked as a planter and house carpenter and served in King Philip's War, as did his third child, Philip (Ebenezer's father).

Roger is believed to be the ancestor of most people bearing the surname Eastman in the United States.[6] Notable descendants bearing his name include Kodak founder George Eastman, painter Seth Eastman, and physician Charles Eastman.

"Eastman" is an Anglo-Saxon patronymic surname derived from the old English personal name Estmund, meaning grace ("est") and protection ("mund"). [7]

Early life

Birth and family

Ebenezer Eastman was born on February 17, 1681, to Philip Eastman, Sr. (October 20, 1644 - October 7, 1714, to November 13, 1714) and Mary Barnard Eastman (September 22, 1645 - June 5, 1712) in Haverhill, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British America. Mary was a widow after her husband had died in 1678. She would marry Philip Sr., who had also lost his spouse, less than six months after her husband's death. Mary had four children with her husband before he passed and would go on to mother another five with Philip, Sr. Amongst Philip, Sr.'s and Mary's children, Ebenezer was the middle child and oldest son. Philip, Sr. had fought in King Philip's War.[8]

Raid on Haverhill

On the dawn of March 15, 1697, when Ebenezer was sixteen, the Governor General of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac gave orders for French, Algonquin, and Abenaki warriors to stage a surprise attack on Haverhill. Twenty-seven Massachusetts Bay colonists were killed, thirteen were captured, and six homes were destroyed by fire, Philip Eastman Sr.'s among them. He and other members of his family were taken captive in the chaos, but all except for his son-in-law, Thomas Wood, survived and were eventually freed. Having no home to return to in Haverhill, Philip, Sr. relocated to Woodstock, Connecticut, where his son, Philip Jr., had settled.[9]

Queen Anne's War

Siege of Port Royal

At the age of 26, Ebenezer Eastman joined the regiment of Colonel Wainwright in the expedition against Port Royal. What role he played in the siege, as with his motivation behind taking part in it, is no longer known.[10]

Quebec Expedition

In 1711, a British fleet under Admiral Hovenden Walker arrived in Boston with the intention of attacking Quebec City. Eastman, 30 years old, had command of a company of infantry and was to follow the admiral aboard a transport.[11] The fleet was well-supplied by the province but had difficulty securing pilots and accurate charts for navigating the waters of the lower Saint Lawrence River.

After reaching the Gulf of Saint Lawrence without incident by August 3, the fleet was met with unforgiving wind and fog. By August 11, the wind had freshened, and the fog had irregular breaks, but not enough to give sight of land.

At around 8:00pm on August 22, Admiral Walker gave the signal to head roughly southwest. The transports, one of which Eastman was on board, were ordered to follow the admiral's ship, which had a large light hoisted at masthead. Eastman had navigated the river many times before and was familiar with how treacherous the waters could be. In the night, the admiral's light became obscured at a time when the fleet was "doubling a very dangerous and rocky point or cape." After the admiral's ship had doubled the point and moved into line, the light became visible again but created an illusion that appeared to show the admiral directly at that dangerous point.

Eastman informed his commander of the danger ahead and begged him to alter course. His commander, intoxicated at the time, refused, emphatically stating that "he would follow his admiral if he went to hell". Eastman replied that he "would go there himself" if he didn't act, and quipped that he himself had "no in notion of going there." Eastman assumed command, telling the crew of the danger they were in, and ordering the captain and helmsman to change course. The crew, thus alarmed, quickly complied.

Eastman's tenacity rescued the ship from the doom that befell the 890 men and women who were wrecked on the very crags that he had warned of. The next morning, the humbled captain begged for Eastman's friendship, but eventually the admiral himself came aboard Eastman's ship. After seeing Eastman, Admiral Walker questioned, "Captain Eastman, where were you when the fleet was cast away?"[12] to which Eastman replied: "Following my admiral."[13]

A total of seven transports and one storeship were lost in the accident, which remains one of the worst naval disasters in British history.[14]

Personal life

Marriage and children

On March 4, 1710, Ebenezer Eastman married his first cousin, Sarah Peasley of Haverill.[15] Sarah and Ebenezer shared a maternal grandfather, Thomas Barnard, who was one of the original settlers of Amesbury, Massachusetts.[16]

Ebenezer and Sarah had nine children together over the course of 20 years: Ebenezer, Jr., Philip, Joseph, Nathaniel, Jeremiah, Obadiah, Sarah, Jr., Ruth, and Moses. Eight of the nine survived to adulthood, with four of them living past the age of 80.

The family settled in Concord in 1726.[17] Joseph (b. 1716) served as selectman for Concord alongside his father in 1732.[18] Their daughter Sarah (b. 1724) died in 1737. In 1745, Ebenezer, Jr. enlisted in John Goffe's company of thirty-seven scouts. Philip was remembered as "one of the most useful citizens of his generation." Three of Ebenezer's sons: Joseph, Nathaniel, and Moses, fought in the American Revolutionary War.

King George's War

King George's War

Captain Ebenezer Eastman is recorded as having visited Cape Breton twice.[19] On March 1, 1745, he was in the command of a company on the first occasion. During this venture he was present at the Siege of Louisbourg. This siege consisted of a New England colonial force, aided by a British fleet. Although his first time at Cape Breton, this was his second time in Nova Scotia, the first being in 1707 during failed the sieges on Port Royal.[20]

Returning back home on November 10, 1746, Captain Eastman made his way back to Cape Breton early the next year. He returned home on July 9, 1746.[21]

Final years

Bradley Massacre

Shortly after Ebenezer's return from Canada, on August 11, 1746, a massacre took place in Concord. On the tenth of August, Captain Ladd came up to what was at the time called Rumford. Lieutenant Jonathan Bradley took six of Captain Ladd's men and was accompanied by an Obadiah Peters who belonged to Captain Melvin's Company of the Massachusetts. They were traveling about two and a half miles to a garrison outside of Rumford. Upon going about a half mile, they were ambushed by "thirty or forty Indians, if not more".[22] Five of the eight men present were "killed down dead on the spot". Two of the survivors were taken captive, while the other surviving member of the party managed to escape without being caught, having killed a Native American who was trying to capture him. Among the dead were Jonathan and Samuel Bradley, brothers-in-law to Ebenezer's son Philip. Captain Eastman was in a garrison with his family on the east side of the Merrimack River at the time of the attack.[23] When news reached Philip, he and his wife Abiah rode "at full canter" to Captain Eastman's fort.[24]

Unfinished House

The garrison that the Eastman family resided at during the massacre in Penacook[25] was the site of a large two-story house. Ebenezer died before the house was completed.[26]

Ebenezer's son, Philip, owned a home on 215 Eastman Street in East Concord. A photograph of the home, constructed c. 1755, can be viewed on the New Hampshire Historical Society's website.

Death and Will

Ebenezer Eastman died at the age of 67 on July 28, 1748, in Concord, New Hampshire.[27] His cause of death is unrecorded.

Ebenezer's will was dated March 7, 1744, four years before his death.[28] His wife, Sarah, was bequeathed his "house and former homestead in Haverhill, his land in Concord, three cows, a horse, all of his household goods, and a slave by the name of Cesar."[29][30] Less than a month after the will was written, Sarah died at the age of 53. The will provided that, in the case of her death, all of property was to be divided equally among their children, excepting Joseph, who was to be given "one hundred pounds old tenor" as Ebenezer had already given him "the value thereof by deed".[31]

An inventory report[32] made on November 25, 1748, appraised Captain Eastman's estate at £7,901, equivalent to £1,179,586 in 2019.[33]

Legacy

Ebenezer Eastman Memorial Clock

In East Concord, Eastman is memorialized by a granite clock installed in 1924 celebrating his ostensible founding achievement. The monument was erected by the Eastman Family Memorial Association.[34]

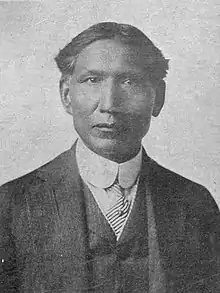

Descendants

Eastman has multiple notable direct descendants. Seth Eastman, a West Point graduate and Civil War veteran commissioned by Congress to create paintings for the United States Capitol, was Captain Eastman's great-great grandson.[35] Seth's grandson Charles Alexander Eastman, of the Dakota people, was one of the first Native Americans to be certified as a European-style doctor, a co-founder of the Boy Scouts, and a historian.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ Rix, Guy (1901). History and Genealogy of the Eastman Family of America. Concord, New Hampshire: I.C. Evans.

- ↑ Bouton, Nathaniel (1856). The History of Concord, From its First Grant in 1725, to the Organization of the City Government in 1853, With a History of the Ancient Penacooks. Concord, New Hampshire: B. W. Sanborn.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, p. 551.

- ↑ Eastman 1952, pg. 3

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 8.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 8.

- ↑ https://coadb.com/surnames/eastman-arms.html

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 10.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 8.

- ↑ Boutoun 1856, pg. 551-552.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 21.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 552

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 22

- ↑ Graham, Gerald S. (1979) [1969]. "Walker, Sir Hovenden". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 20.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 21.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 21.

- ↑ Moore, Jacob (1824). Annals of the Town of Concord, in the County of Merrimack, and State of New-Hampshire From Its First Settlement, in the Year 1726, to the Year 1823. Concord, New Hampshire: J. B. Moore.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 553.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 21.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 553.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 158

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 553.

- ↑ "Philip Eastman House, 215 Eastman Street, undated". New Hampshire Historical Society. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 553.

- ↑ Bouton 1856, pg. 553.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 23.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 24.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 23-24

- ↑ Rix 1901. pg. 25.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 24.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 24.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 25-26

- ↑ "Capt. Ebenezer Eastman memorial, 1924". New Hampshire Historical Society. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ↑ Rix 1901, pg. 301.

- ↑ Eastman, Charles (1952). That Man Eastman. Hollywood, California: C.J. Eastman.