| ||

|---|---|---|

|

40th & 42nd Governor of Arkansas

42nd President of the United States

Policies

Appointments

First term

Second term

Presidential campaigns Controversies

Post-presidency

|

||

The economic policies of Bill Clinton administration, referred to by some as Clintonomics, encapsulates the economic policies of president of the United States Bill Clinton that were implemented during his presidency, which lasted from January 1993 to January 2001.

President Clinton oversaw a healthy economy during his tenure. The U.S. had strong economic growth (around 4% annually) and record job creation (22.7 million). He raised taxes on higher income taxpayers early in his first term and cut defense spending and welfare, which contributed to a rise in revenue and decline in spending relative to the size of the economy. These factors helped bring the United States federal budget into surplus from fiscal years 1998 to 2001, the only surplus years since 1969. Debt held by the public, a primary measure of the national debt, fell relative to GDP throughout his two terms, from 47.8% in 1993 to 31.4% in 2001.[1]

Clinton signed North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) into law, along with many other free trade agreements. He also enacted significant welfare reform. His deregulation of finance (both tacit and overt through the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act) has been criticized as a contributing factor to the Great Recession.[2]

Overview

Clinton's presidency included a great period of economic growth in America's history. Clintonomics encompassed both a set of economic policies as well as governmental philosophy. Clinton's economic approach entailed modernization of the federal government, making it more enterprise-friendly while dispensing greater authority to state and local governments. The ultimate goal involved rendering the American government smaller, less wasteful, and more agile in light of a newly globalized era.[3]

Clinton assumed office following the end of a recession, and the economic practices he implemented are held up by his supporters as having fostered a recovery and surplus, though some of the president's critics remained more skeptical of the cause-effect outcome of his initiatives. The Clintonomics policy focus could be summarized by the following four goals:

- Establish fiscal discipline and eliminate the budget deficit

- Maintain low interest rates and encourage private-sector investment

- Eliminate protectionist tariffs

- Invest in human capital through education and research

Prior to the 1992 presidential campaign, America had undergone twelve years of conservative policies implemented by Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. Clinton ran on the economic platform of balancing the budget, lowering inflation, lowering unemployment, and continuing the traditionally conservative policies of free trade.

David Greenberg, a professor of history and media studies at Rutgers University, opined that:

The Clinton years were unquestionably a time of progress, especially on the economy ... Clinton's 1992 slogan, 'Putting people first,' and his stress on 'the economy, stupid,' pitched an optimistic if still gritty populism at a middle class that had suffered under Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. ... By the end of the Clinton presidency, the numbers were uniformly impressive. Besides the record-high surpluses and the record-low poverty rates, the economy could boast the longest economic expansion in history; the lowest unemployment since the early 1970s; and the lowest poverty rates for single mothers, black Americans, and the aged.[4]

Fiscal policy

Tax reform

In proposing a plan to cut the deficit, Clinton submitted a budget and corresponding tax legislation (the final, signed version was known as the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993) that would cut the deficit by $500 billion over five years by reducing $255 billion of spending and raising taxes on the wealthiest 1.2% of Americans.[5] It also imposed a new energy tax on all Americans and subjected about a quarter of those receiving Social Security payments to higher taxes on their benefits.[6]

Republican Congressional leaders launched an aggressive opposition against the bill, claiming that the tax increase would only make matters worse. Republicans were united in this opposition, and every Republican in both houses of Congress voted against the proposal. In fact, it took Vice President Gore's tie-breaking vote in the Senate to pass the bill.[7] After extensive lobbying by the Clinton Administration, the House narrowly voted in favor of the bill by a vote of 218 to 216.[8] The budget package expanded the earned income tax credit (EITC) as relief to low-income families. It reduced the amount they paid in federal income and Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax (FICA), providing $21 billion in savings for 15 million low-income families.

Clinton signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 into law on August 10, 1993.[9] The law created a 36 percent to 39.6 percent income tax for high-income individuals in the top 1.2% of wage earners. Businesses were given an income tax rate of 35%. The cap was repealed on Medicare. Gas taxes were raised 4.3 cents per gallon. The taxable portion of Social Security benefits were also increased.

Clinton signed Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996 which reduced taxes for many small business. Furthermore, he signed legislation that increased the tax deduction for self-employed business owners from 30% to 80% by 1997. The Taxpayer Relief Act reduced some federal taxes. The 28% rate for capital gains was lowered to 20%. The 15% rate was lowered to 10%. In 1980, a tax credit was put into place based on the number of individuals under the age of 17 in a household. In 1998, it was $400 per child and in 1999, it was raised to $500. This Act removed from taxation profits on the sale of a house of up to $500,000 for individuals who are married, and $250,000 for single individuals. Educational savings and retirement funds were given tax relief. Some of the expiring tax provisions were extended for selected businesses. Since 1998, an exemption could be taken out for those family farms and small businesses that qualified for it. In 1999, the correction of inflation on the $10,000 annual gift tax exclusion was accomplished. By the year 2006, the $600,000 estate tax exemption had risen to $1 million.

The economy continued to grow, and in February 2000 it broke the record for the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in U.S. history.[10][11]

After Republicans won control of Congress in 1994, Clinton vehemently fought their proposed tax cuts, believing that they favored the wealthy and would weaken economic growth. In August 1997, however, Clinton and Congressional Republicans were finally able to reach a compromise on a bill that reduced capital gain and estate taxes and gave taxpayers a credit of $500 per child and tax credits for college tuition and expenses. The bill also called for a new individual retirement account (IRA) called the Roth IRA to allow people to invest taxed income for retirement without having to pay taxes upon withdrawal. Additionally, the law raised the national minimum for cigarette taxes. The next year, Congress approved Clinton's proposal to make college more affordable by expanding federal student financial aid through Pell Grants, and lowering interest rates on student loans.

Clinton also battled Congress nearly every session on the federal budget, in an attempt to secure spending on education, government entitlements, the environment, and AmeriCorps–the national service program that was passed by the Democratic Congress in the early days of the Clinton administration. The two sides, however, could not find a compromise and the budget battle came to a stalemate in 1995 over proposed cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, education, and the environment. After Clinton vetoed numerous Republican spending bills, Republicans in Congress twice refused to pass temporary spending authorizations, forcing the federal government to partially shut down because agencies had no budget on which to operate.[12] In April 1996, Clinton and Congress finally agreed on a budget that provided money for government agencies until the end of the fiscal year in October. The budget included some of the spending cuts that the Republicans supported (decreasing the cost of cultural, labor, and housing programs) but also preserved many programs that Clinton wanted, including educational and environmental ones.

Deficits and debt

Below are the budgetary results for President Clinton's two terms in office:

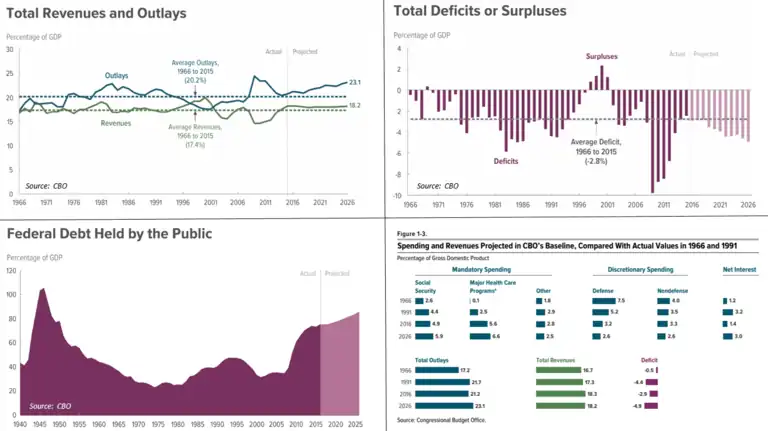

- He had budget surpluses for fiscal years 1998–2001, the only such years from 1970 to 2023. Clinton's final four budgets were balanced budgets with surpluses, beginning with the 1997 budget.

- The ratio of debt held by the public to GDP, a primary measure of U.S. federal debt, fell from 47.8% in 1993 to 33.6% by 2000. Debt held by the public was actually paid down by $453 billion over the 1998-2001 periods, the only time this happened between 1970 and 2018.

- Federal spending fell from 20.7% GDP in 1993 to 17.6% GDP in 2000, below the historical average (1966 to 2015) of 20.2% GDP.

- Tax revenues rose steadily from 17.0% GDP in 1993 to 20.0% GDP in 2000, well above the historical average of 17.4% GDP.

- Defense spending fell from 4.3% GDP in 1993 to 2.9% GDP by 2000, as the U.S. enjoyed a "peace dividend" in the wake of the fall of the Soviet Union. In dollar terms, defense spending fell from $292B in 1993 to $266B by 1996, then slowly rose to $295 billion by 2000.

- Non-defense discretionary spending fell from 3.6% GDP in 1993 to 3.2% GDP by 2000. In dollar terms, it grew from $248B in 1993 to $343B in 2000; robust economic growth still enabled the ratio to fall relative to GDP.[1]

These surpluses 1998-2001 were attributed to a strong economy generating high tax revenues, tax increases on upper-income taxpayers, spending restraint, and capital gains tax revenue from a stock market boom.[13] This pattern of raising taxes and cutting spending (i.e., austerity) in an economic boom coincides precisely with the advice of John Maynard Keynes, who stated in 1937: "The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury."[14] However, this remarkable success did not stop conservative pundits from trying to discredit this achievement. Their argument essentially goes like this: Although debt held by the public was reduced, the surplus funds paid into Social Security were used to pay those bondholders, in effect borrowing from one pocket (future Social Security program recipients) to pay down the other (current bondholders), such that total debt rose. However, while this is true, this is also how the proverbial "math works" for all the other modern Presidents as well. It is not accurate to discredit the exceptional fiscal austerity of the Clinton era relative to other modern Presidents, which nevertheless coincided with a booming economy by virtually any measure.[15] It is also relevant to point out that this booming economy occurred despite Republican warnings that such tax increases on the highest income taxpayers would slow the economy and job creation. Perhaps the boom would have been even greater if larger deficits had been run, but this was not the argument made at the time.

Welfare reform

On taking office in early 1993, Clinton proposed a $16 billion stimulus package primarily to aid urban area programs favored by progressives. The package was quickly defeated by a Republican filibuster in the Senate.[16] Serious efforts at welfare reform required bipartisan support. With the landslide Republican win in the 1994 midterm elections, Clinton was forced to triangulate policies, wherein he adopted mostly conservative proposals supported by most Republicans, while claiming the major credit for them.[17]

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA) of 1996 established the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) food assistance program, which was funded by block grants to the states. This program replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which had open-ended funding for those who qualified and a federal match for state spending. To receive the full TANF grant amounts, states had to meet certain requirements related to their own spending, as well as the percentage of recipients working or participating in training programs. This threshold could be reduced if welfare caseloads fell. The law also modified the eligibility rules for means-tested benefits programs such as food stamps and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).[18]

CBO estimated in March 1999 that the TANF basic block grant (authorization to spend) would total $16.5 billion annually through 2002, with the amount allocated to each state based on the state's spending history. These block grant amounts proved to be more than the states could initially spend, as AFDC and TANF caseloads dropped by 40% from 1994 to 1998 due to the booming economy. As a result, states had accumulated surpluses which could be spent in future years. States also had the flexibility to use these funds for child care and other programs. CBO also estimated that TANF outlays (actual spending) would total $12.6 billion in fiscal years 1999 and 2000, grow to $14.2 billion by 2002, and reach $19.4 billion by 2009. For scale, total spending in FY 2000 was approximately $2,000 billion, so this represents around 0.6%. Further, CBO estimated that unspent balances would grow from $7.1 billion in 2005 to $25.4 billion by 2008.[19]

The law's effect goes far beyond the minor budget impact, however. The Brookings Institution reported in 2006 that: "With its emphasis on work, time limits, and sanctions against states that did not place a large fraction of its caseload in work programs and against individuals who refused to meet state work requirements, TANF was a historic reversal of the entitlement welfare represented by AFDC. If the 1996 reforms had their intended effect of reducing welfare dependency, a leading indicator of success would be a declining welfare caseload. TANF administrative data reported by states to the federal government show that caseloads began declining in the spring of 1994 and fell even more rapidly after the federal legislation was enacted in 1996. Between 1994 and 2005, the caseload declined about 60 percent. The number of families receiving cash welfare is now the lowest it has been since 1969, and the percentage of children on welfare is lower than it has been since 1966." The effects were particularly significant on single mothers; the portion of employed single mothers grew from 58% in 1993 to 75% by 2000. Employment among never-married mothers increased from 44% to 66%. The report concluded that: "The pattern is clear: earnings up, welfare down. This is the very definition of reducing welfare dependency."[20]

Trade

.SVG.png.webp)

Clinton made it one of his goals as president to pass trade legislation that lowered the barriers to trade with other nations. He broke with many of his supporters, including labor unions, and those in his own party to support free-trade legislation.[22] Opponents argued that lowering tariffs and relaxing rules on imports would cost American jobs because people would buy cheaper products from other countries. Clinton countered that free trade would help America because it would allow the U.S. to boost its exports and grow the economy. Clinton also believed that free trade could help move foreign nations to economic and political reform.

The Clinton administration negotiated a total of about 300 trade agreements with other countries.[23] Clinton's last treasury secretary, Lawrence Summers, stated that the lowered tariffs that resulted from Clinton's trade policies, which reduced prices to consumers and kept inflation low, were technically "the largest tax cut in the history of the world."[24]

NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the free trade agreement between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, was signed by President George H. W. Bush in December 1992, pending its ratification by the legislatures of the three countries. Clinton did not alter the original agreement, but complemented it with the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation and the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation, making NAFTA the first "green" trade treaty and the first trade treaty concerned with each country's labor laws, albeit with very weak sanctions.[25] NAFTA provided for gradually reduced tariffs and the creation of a free-trade bloc between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Opponents of NAFTA, led by 1992 independent presidential candidate Ross Perot, claimed it would force American companies to move their workforces to Mexico, where they could produce goods with cheaper labor and ship them back to the United States at lower prices. Clinton, however, argued that NAFTA would increase U.S. exports and create new jobs.

When he signed NAFTA, Clinton said: "NAFTA means jobs. American jobs, and good-paying American jobs. If I didn't believe that, I wouldn't support this agreement."[26] He convinced many Democrats to join most Republicans in supporting trade agreement and in 1993 the Congress passed the treaty.[27]

While economists generally view free trade as an overall positive for the nation's involved, certain groups may be adversely affected, such as manufacturing workers. For example:

- In a 2012 survey of leading economists, 95% supported the notion that on average, U.S. citizens benefited on NAFTA.[28] A 2001 Journal of Economic Perspectives review found that NAFTA was a net benefit to the United States. A 2015 study found that US welfare increased by 0.08% as a result of the NAFTA tariff reductions, and that US intra-bloc trade increased by 41%.

- In 2015, the Congressional Research Service concluded that the "net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment among their economies." CRS also pointed out that NAFTA to a great extent set rules for behavior already underway (e.g., U.S. manufacturing companies were already moving some jobs to Mexico, thus avoiding U.S. employment regulation and unions, in efforts to maximize profits.)[29]

- The United States Chamber of Commerce credits NAFTA with increasing U.S. trade in goods and services with Canada and Mexico from $337 billion in 1993 to $1.2 trillion in 2011, while the AFL–CIO blames the agreement for sending 700,000 American manufacturing jobs to Mexico over that time.[30]

World Trade Organization (WTO)

Officials in the Clinton administration also participated in the final round of trade negotiations sponsored by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), an international trade organization. The negotiations had been ongoing since 1986. In a rare move, Clinton convened Congress to ratify the trade agreement in the winter of 1994, during which the treaty was approved. As part of the GATT agreement, a new international trade body, the World Trade Organization (WTO), replaced GATT in 1995. The new WTO had stronger authority to enforce trade agreements and covered a wider range of trade than did GATT.

Asia

Clinton also held meetings with leaders of Pacific Rim nations to discuss lowering trade barriers. In November 1993, he hosted a meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Seattle, Washington, which was attended by the leaders of 12 Pacific Rim nations. In 1994, Clinton arranged an agreement in Indonesia with Pacific Rim nations to gradually remove trade barriers and open their markets.

Clinton faced his first defeat on trade legislation during his second term. In November 1997, the Republican-controlled Congress delayed voting on a bill to restore a presidential trade authority that had expired in 1994. The bill would have given the president the authority to negotiate trade agreements which the Congress was not authorized to modify–known as "fast-track negotiating" because it streamlines the treaty process. Clinton was unable to generate sufficient support for the legislation, even among the Democratic Party.

Clinton faced yet another trade setback in December 1999, when the WTO met in Seattle for a new round of trade negotiations. Clinton hoped that new agreements on issues such as agriculture and intellectual property could be proposed at the meeting, but the talks fell through. Anti-WTO protesters in the streets of Seattle disrupted the meetings[31] and the international delegates attending the meetings were unable to compromise mainly because delegates from smaller, poorer countries resisted Clinton's efforts to discuss labor and environmental standards.[32]

That same year, Clinton signed a landmark trade agreement with the People's Republic of China. The agreement–the result of more than a decade of negotiations–would lower many trade barriers between the two countries, making it easier to export U.S. products such as automobiles, banking services, and motion pictures. However, the agreement could only take effect if China was accepted into the WTO and was granted permanent "normal trade relations" status by the U.S. Congress. Under the pact, the United States would support China's membership in the WTO. Many Democrats as well as Republicans were reluctant to grant permanent status to China because they were concerned about human rights in the country and the impact of Chinese imports on U.S. industries and jobs. Congress, however, voted in 2000 to grant permanent normal trade relations with China. Several economic studies have since been released that indicate the increase in trade resulting lowered American prices and increased the U.S. GDP by 0.7% throughout the following decade.[33]

Agriculture

Although Governor Clinton had a large farm base in Arkansas; as president he sharply cut support for farmers and raised taxes on tobacco.[34] At one high level policy meeting budget expert Alice Rivlin told the president she had a new slogan for his reelection campaign: "I’m going to end welfare as we know it for farmers.” Clinton was annoyed and retorted, “Farmers are good people. I know we have to do these things. We’re going to make these cuts. But we don’t have to feel good about it.”[35]

With exports accounting for more than a fourth of farm output, farm organizations joined business interests to defeat human rights activists regarding Most Favored Nation (MFN) trade status for China They took the position that major tariff increases would hurt importers and consumers. They warned that China would retaliate to hurt American exporters. They wanted more liberal trade policies and less attention to internal Chinese human rights abuses.[36]

Environmentalists began taking a keen interest in agricultural policies. The feared that farming had a growing negative impact on the environment in terms of soil erosion and the destruction of wetlands. The expanding use of pesticides and fertilizers, polluted soil and water not just on each farm but downstream into rivers and lakes and urban areas as well.[37] A major issue involved low fees charged ranchers who grazed cattle on public lands. The "animal unit month" (AUM) fee was only $1.35 and was far below the 1983 market value. The argument was that the federal government in effect was subsidizing ranchers, with a few major corporations controlling millions of acres of grazing land. Babbitt and Oklahoma Congressman Mike Synar tried to rally environmentalists and raise fees, but senators from the Western United States successfully blocked their proposals.[38][39]

Congress wrote a new farm bill in 1995. Clinton vetoed it on December 6, 1995 because it would "eliminate the safety net" and "provide windfall payments to producers when prices are high, but not protect family farm income would prices or low."[40]

Deregulation of banking

Clinton signed the bipartisan Financial Services Modernization Act or GLBA in 1999.[41] It allowed banks, insurance companies and investment houses to merge and thus repealed the Glass-Steagall Act which had been in place since 1932. It also prevented further regulation of risky financial derivatives. His deregulation of finance (both tacit and overt through GLBA) was criticized as a contributing factor to the Great Recession. While he disputes that claim, he expressed regret and conceded that in hindsight he would have vetoed the bill, mainly because it excluded risky financial derivatives from regulation, not because it removed the long-standing Glass-Steagall barrier between investment and depository banking. In his view, even if he had vetoed the bill, the Congress would have overridden the veto, as it had nearly unanimous support.[2]

Politifact in 2015 rated Clinton's claim that repeal of Glass-Steagall did not have "anything to do with the financial crash [of 2008]" as "Mostly True," with the caveat that his claim focused on removing the separation of investment and depository banking and not the broader exclusion of risky financial instruments (derivatives) from regulation.[42] These derivatives, such as the credit default swaps at the core of the 2008 crisis, were basically used to insure mortgage-related securities, with AIG the major provider. This encouraged more mortgage-related lending, as AIG theoretically stood behind the mortgage securities used to finance the mortgage lending. However, AIG was not effectively regulated and did not have the financial resources to make good on its insurance promises when housing defaults began and investors began to claim the insurance payments on mortgage securities in default. AIG collapsed spectacularly in September 2008, and became a conduit for a large government bailout (over $100 billion) to many banks globally to which AIG owed money, one of the darkest episodes in the crisis.[43]

Economic results summary

Overall

Clinton presided over the following economic results, measured from January 1993 to December 2000, with alternate dates as indicated:

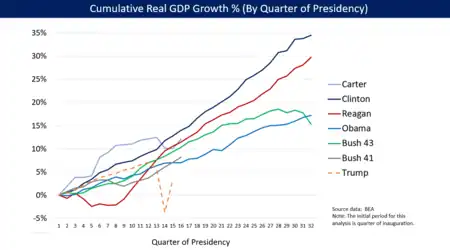

- Average real GDP growth of 3.8%, compared to average growth of 3.1% from 1970 to 1992. The economy grew every quarter.[45]

- Real GDP per capita increased from about $36,000 in 1992 to $44,470 in 2000 (in 2009 dollars), about 23%, roughly the same as it did from 1981 to 1989 during the Reagan administration.[46]

- Inflation averaged 2.6%, versus 6.1% from 1970 to 1992 and 3.0% in 1992.[47]

Labor market

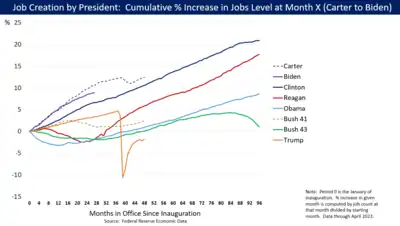

- Non-farm payrolls increased by 22.7 million from February 1993 to January 2001 (236,000 per month average, the fastest on record for a Presidential tenure[48]) while civilian employment increased by 18.5 million (193,000 per month average).[49]

- The unemployment rate was 7.3% in January 1993, fell steadily to 3.8% by April 2000 and was 4.2% in January 2001 when his second term ended. It was below 5.0% after May 1997.[50]

- Unemployment for African Americans fell from 14.1% in January 1993 to 7.0% in April 2000, the lowest rate on record.[50]

- Unemployment for Hispanics fell from 11.3% in January 1993 to 5.1% in October 2000, the lowest rate on record up to that point.[50]

Households

- Real median household income increased from $50,725 in 1992 to $57,790 in 2000, a 13.9% increase.[51]

- The poverty rate declined from 15.1% in 1993 to 11.3% in 2000, the largest six-year drop in poverty in nearly 30 years. The number in poverty fell from 39.2 million in 1993 to 31.58 million in 2000, a decline of 7.6 million.[52]

- The homeownership rate reached 67.7% near the end of the Clinton administration, the highest rate on record. In contrast, the homeownership rate fell from 65.6% in the first quarter of 1981 to 63.7% in the first quarter of 1993.[53]

- Clinton worked with the Republican-led Congress to enact welfare reform. As a result, welfare rolls dropped dramatically and were the lowest since 1969. Between January 1993 and September 1999, the number of welfare recipients dropped by 7.5 million (a 53% decline) to 6.6 million. In comparison, between 1981 and 1992, the number of welfare recipients increased by 2.5 million (a 22% increase) to 13.6 million people.[54]

Criticism

Clinton has been heavily criticized for overseeing the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which made it more affordable for manufacturing companies to outsource jobs to foreign countries and then import their product back to the United States.

Some liberals and nearly all progressives believe that Clinton did not do enough to reverse the trends toward widening income and wealth inequality that began in the late 1970s and 1980s. The top marginal income tax rate for high-income individuals (the top 1.2% of earners) was 70 percent in 1980, then lowered to 28 percent in 1986 by Reagan; Clinton raised it back to 39.6 percent, but it remained far below pre-Reagan levels. Clinton's administration also afforded no benefit to unionized labor and did not favor strengthening collective bargaining rights.

Lower unemployment rates were another large part of Clinton's macroeconomic policies. Many argue that Clinton cost many Americans jobs because he supported free trade, which some argue caused the U.S. to lose jobs to countries like China (Burns and Taylor 390). Even if Clinton did cost Americans some jobs because of free trade support, some claim that he allowed for more jobs than were lost because the unemployment rate of his presidency, and especially his second term, were the lowest they had been in thirty years (Burns and Taylor 390). Others attribute this to sustained declines in interest rates, which fueled a booming stock market and job growth in a booming technology sector.

As mentioned previously, Clinton has been criticized by some observers as having played a long-term role in leading to the Great Recession with the aforementioned Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act as well as the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "CBO Budget and Economic Outlook 2016-2026 Historical tables". CBO. 25 January 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- 1 2 "Bill Clinton fires back at critics of his financial regulatory policies". The Hill. May 14, 2014. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ Jack Godwin, Clintonomics: How Bill Clinton Reengineered the Reagan Revolution (Amacom Books, 2009)

- ↑ "Memo to Obama Fans: Clinton's presidency was not a failure". Slate. Retrieved February 13, 2005.

- ↑ Speech by President Address to Joint Session of Congress February 17, 1993 Archived March 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Asking American to 'Face Facts,' Clinton Presents Plan to Raise Taxes, Cut Deficit". The Washington Post. February 18, 1993. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate Roll Call Vote – H.R. 2264 (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993)". Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ↑ U.S. House Recorded Vote – H.R. 2264 (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993)

- ↑ Sabo, Martin Olav (1993-08-10). "H.R.2264 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-13.

- ↑ Bryant, Nick (January 15, 2001). "How history will judge Bill Clinton". BBC News. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

That he has presided over the longest economic expansion in US history is undeniable. The US entered its 107th consecutive month of growth last February.

- ↑ Schifferes, Steve (January 15, 2001). "Bill Clinton's economic legacy". BBC News. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Government Shutdown Battle" – PBS

- ↑ "The Budget and Deficit Under Clinton". February 3, 2008 – via factcheck.org.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul (30 December 2011). "Keynes was right". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Bill Clinton says his administration paid down the debt". PolitiFact.com. September 23, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ↑ Elizabeth Drew, On the Edge: The Clinton Presidency (1994) pp 114–122.

- ↑ Bruce F. Nesmith, and Paul J. Quirk, "Triangulation: Position and Leadership in Clinton’s Domestic Policy." in 42: Inside the Presidency of Bill Clinton edited by Michael Nelson at al. (Cornell UP, 2016) pp. 46-76.

- ↑ "The Economic and Budget Outlook:Fiscal Years 1999-2008". CBO. January 8, 1998. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Testimony on CBO's Spending Projections for the TANF and Federal Child Care Programs". CBO. March 16, 1999. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ "The Outcomes of 1996 Welfare Reform". CBO. July 19, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ↑ Kate Bronfenbrenner, 'We'll Close', The Multinational Monitor, March 1997, based on the study she directed, 'Final Report: The Effects of Plant Closing or Threat of Plant Closing on the Right of Workers to Organize'.

- ↑ AFL CIO on Trade Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Clinton on Foreign Policy at University of Nebraska Archived 2015-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Address by Lawrence H. Summers, Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ North American Free Trade Agreement

- ↑ "Remarks by President Clinton, President Bush, President Carter, President Ford, and Vice President Gore in Signing of Nafta Side Agreements". www.historycentral.com. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ↑ Roll Call Vote – H.R. 3450

- ↑ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)" (PDF).

- ↑ 2 Dec 2013"Contentious Nafta pact continues to generate a sparky debate" By James Politi

- ↑ Security Increased for WTO Protests – PBS

- ↑ Wrapping Up the WTO – PBS

- ↑ Council on Foreign Relations (2007). U.S.-China Relations: An Affirmative Agenda, a Responsible Course, p. 62

- ↑ For his farm policies see Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: A Review of Government and Politics. Vol 9 1993-1996 (1998) pp 479-508; Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: Volume 10: 1997-2001 (2002) pp 417-428.

- ↑ Bob Woodward, The Agenda (2002) pp. 127–128.

- ↑ John W. Dietrich, "Interest groups and foreign policy: Clinton and the China MFN debates." Presidential Studies Quarterly 29.2 (1999): 280-296 online.

- ↑ CQ, Congress and the Nation: 1989–1992 (1993) p. 536.

- ↑ Richard Lowitt, “Oklahoma's Mike Synar Confronts the Western Grazing Question, 1987-2000,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly (2004) 47#2 pp 77-111

- ↑ Julie Andersen Hill, "Public Lands Council v. Babbitt: Herding Ranchers Off Public Land." BYU Law Review (2000): 1273+ online.

- ↑ CQ, Congress and the Nation. Vol 9 1993-1996 (1998) p 496.

- ↑ CQ, Congress and the Nation Vol 10 1997-2001 (2002) pp 130–140.

- ↑ "Bill Clinton:Glass-Steagall repeal had nothing to do with financial crisis". Politifact.com. August 19, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission-Conclusions". FCIC.law.stanford.edu. January 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ FRED-Real GDP-Retrieved July 1, 2018

- ↑ "FRED Real GDP". FRED. April 1947. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ↑ "FRED Real GDP per Capita". FRED. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ↑ "FRED CPI and 10-Year Treasury". FRED. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Job Creation by President". Politics that Work. 2015.

- ↑ "Civilian Employment and Total Nonfarm Payrolls". FRED. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Unemployment rates by race". FRED. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ↑ "FRED Real median household income". FRED. January 1984. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Historical Poverty Tables". Census.gov. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Office of Management! and Budget; National Economic Council, September 27, 2000

- ↑ HHS Administration for Children and Families, December 1999 and August 2000; White House, Office of the Press Secretary, August 22, 2000

References

- Anonymous. Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. File Tax.Com. 8 Mar. 2008

- Anonymous. "S&P 500." Standard & Poor's. 8 Mar. 2008

- Midgley, James. "The United States: Welfare, Work, and Development." International Journal of Social Welfare 10:7 (2000): 284–293.

- Bartlett, Bruce. “Clinton Economics.” NRO NationalreviewONLINE 7 July 2004. 8 March 2008

- "Bill Clinton’s Economic Legacy." BBC. 15 January 2001. British Broadcast Corporation. 8 March 2008

- Bartlett, Bruce. "Those Were the Days." The New York Times. 1 July 2004. 4 March 2008

- Burns, John W. and Andrew J. Taylor. "A New Democrat? The Economic Performance of the Clinton Presidency." The Independent Review V.3 (2001): 387-408.

Further reading

- Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation: IX 1993-1996 (1998)

- Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation: X 1997-2000 (2002)

- Frankel, Jeffrey A. and Peter R. Orszag, eds. American Economic Policy in the 1990s (2002) introduction

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. The roaring nineties : a new history of the world's most prosperous decade (2003) online

primary sources

- Economic Report of the President (annual) online