The early 1990s recession describes the period of economic downturn affecting much of the Western world in the early 1990s. The impacts of the recession contributed in part to the 1992 U.S. presidential election victory of Bill Clinton over incumbent president George H. W. Bush. The recession also included the resignation of Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney, the reduction of active companies by 15% and unemployment up to nearly 20% in Finland, civil disturbances in the United Kingdom and the growth of discount stores in the United States and beyond.

Primary factors believed to have led to the recession include the following: restrictive monetary policy enacted by central banks, primarily in response to inflation concerns, the loss of consumer and business confidence as a result of the 1990 oil price shock,[1] the end of the Cold War and the subsequent decrease in defense spending,[2] the savings and loan crisis and a slump in office construction resulting from overbuilding during the 1980s.[3] The US economy returned to 1980s level growth by 1993[4] and global GDP growth by 1994.[5]

North America

United States

Inverted yield curve in late 1989 and early 1990

Canada

Canada's economy is considered to have been in recession for two full years in the early 1990s, specifically from April 1990 to April 1992.[7][8][lower-alpha 1] Canada's recession began about four months before that of the US, and was deeper, likely because of higher inflationary pressures in Canada, which prompted the Bank of Canada to raise interest rates to levels 5 to 6 percentage points higher than the corresponding rates in the US by early 1990.[10][11]

Canada's economy began to weaken in the second quarter of 1989 as sharp cutbacks in manufacturing output reduced real GDP growth to about 0.3% for each of the last three quarters of the year.[8] Despite GDP growth being minimal, employment growth Canada-wide remained moderate throughout 1989 (although Ontario had a decline in employment in 1989)[12] and there was a solid growth spurt (0.8%) in the first quarter of 1990.[8] In April 1990, economic activity and employment both began substantial declines with the largest drops in real GDP, 1.2%, and employment, 1.1%, occurring in the first quarter of 1991.[8] Both real GDP and employment bounced back in the second quarter of 1991, but then for a full year there was virtually no change in real GDP while employment levels continued to drop as most industries continued to cut output.[8] Only in April 1992 did total employment begin to increase again with real GDP growing 0.4% thereby ending the recession.[8] Technically, the moderate expansion in the second quarter of 1991 would qualify the contractions from April 1990 to March 1991 and July 1991 to April 1992 as two separate recessions, but the 1991 second quarter expansion was likely the result of pent up demand from the Gulf War and the introduction of the federal Goods and Services Tax early in the year severely suppressing consumer spending in the first quarter.[8]

Overall real GDP growth for Canada was 2.3% for 1989, 0.16% for 1990, -2.09% for 1991, 0.90% for 1992, before increasing to 2.66% in 1993.[13] The unemployment rate rose from 7.5% in 1989, to 10.3% in 1990, 10.3% in 1991, 11.2% in 1992, and 11.4% in 1993 before dropping to 10.3% in 1994.[13] In fact, due to unemployment remaining at higher levels until early 1994, some sources assert the early 1990s recession lasted until February 1994 in Canada, as the percentage of the working age population (15-64) being employed continued to decline until the following month.[12] The slow growth in employment following the end of the GDP contraction in April 1992 right through until 1995, is referred to as a "jobless recovery".[14]

Inflation and monetary policy

A key cause of the recession in Canada was inflation and Bank of Canada's resulting monetary policy. The inflation rate in Canada had remained in the 4% range between 1984 and 1988, but began to rise again in 1989, averaging 5.0% that year.[13] Gordon Thiesen, asserted in 2001 when he was the Bank of Canada governor, that inflationary pressures in Canada were partly fueled by Canadians having had a greater "inflation psychology" than Americans, that is a higher propensity to spend now in the belief the price for the same product will be substantially higher in short period of time.[15] To reduce inflation, the Bank of Canada raised its prime rate from 10% in 1986 and 1987, to 12.25% at the start of 1989, peaking at 14.75% in June 1990,[16][17] thereby prompting Canadians to reduce spending, reduce borrowing and begin saving sooner and more greatly than Americans.[15] Particularly hard hit were Canada's real estate markets, the building industry, especially factory construction, and consumer confidence.[11]

Then in February 1991, the Bank of Canada and the Department of Finance announced their monetary policy would be governed by formal inflation targets, with a target of 3% for 1992.[10] Inflation was contained to 4.8% in 1990, 5.6% in 1991 and then decreased to 1.5% in 1992 and 1.9 in 1993, well below the target of 3%.[18] This suggests the Bank of Canada's restrictive monetary policy overshot its target, suppressing GDP and employment growth in 1992 and 1993 in what would normally have been an economic recovery period.[10] In fact, complex macro-economic modelling undertaken estimates that "excessive monetary restraint" of the Bank of Canada reduced real GDP growth by 1.5 percentage points in 1990, 2.9 percentage points in 1991 and 4.0 percentage points in 1993.[10]

Tax increases

Another cause of Canada's recession were several tax increases instituted by the federal government between 1989 and 1991.[10] These increases related to sales, excise and payroll taxes were modelled to have reduced real GDP growth by 1.6, 2.4 and 5.1 percentage points, respectively, in 1990, 1991 and 1992, although if these tax increases had not been implemented the federal government's national debt would have increased a significant amount.[10] A third, less important factor in Canada's recession was the weakness of the US economy at the time, which was calculated to have had the effect of reducing Canada's economic growth by .6, 2.2 and 1.1 percentage points in 1990, 1991 and 1992.[10]

High Value of Canadian Dollar and Low Productivity

An additional reason for the recession, especially it being deeper and longer in Canada than in the US, was the high value of the Canadian dollar, as high as 86-cents American in 1991, which made Canada's export manufactured goods, such as automotive parts, textiles and intermediate industrial goods and materials, uncompetitive in international markets.[11] Combined with Canada's manufacturing productivity at the time being among the lowest in the G7 (caused by a lack of investment in new equipment or in research and development) and the removal of certain protective tariffs through the 1989 Canada-US Free Trade Agreement, this caused substantial job losses in the manufacturing sector with a significant number of manufacturers closing down or moving to the US, Mexico or the Caribbean.[11]

Impact of recession on unemployment

The recession severely depressed job markets throughout the country unemployment rising from a low of 7.2% in October 1989, to a high of 12.1% in November 1992; it would take 10 years before unemployment recovered a 7.2% level (it was reached in October 1999).[6] For instance, in Montreal (Quebec) unemployment affected 16.7% of the active population by December 1992 while the number of households relying on welfare increased from 88,000 to 102,000 between April 1990 and December 1992.[19]

The early 1990s recession was notable for being substantially more negative for employment in Ontario than the early 1980s recession; Ontario's percentage of total age 15-64 population employed began to decline early in 1989 and only began to grow again early in 1994, five years of decline with an 8.2 percentage point drop.[12] By contrast, in the early 1980s Ontario's employment percentage decline was shorter than Canada's as a whole and only had a 4.4 percentage point contraction.[12]

Comparison to early 1980s recession

C.D, Howe Intitute's Business Cycle Council classifies Canada's recession according to their severity, with Category 4 recessions being the second highest after Category 5, which is a depression.[7] It defines Category 4 recessions as having substantial declines in real GDP and employment for a year or longer.[8] The early 1990s recession in Canada is classified as a Category 4 recession, the same category as the early 1980s recession.[7] Notably, the early 1990s recession did not have as deep a contraction as the early 1980s recession, but was of longer duration as it had four years of less than 2.3% growth in real GDP (1989–92), while the early 1980s recession only had two years of less than 2.3% growth (1980 and 1982), and only the early 1990s recession actually saw a decrease in GDP per capita, that being by $29 in 1991.[20] Both recessions had high unemployment after the recessionary period had officially ended with unemployment rates of 12% and 11.4%, in 1983 and 1993, respectively.[20] Other sources describe the early 1990s recession as "the deepest in Canada since the Great Depression of the 1930s" naming it "the Great Canadian Slump of 1990–92."[21]

Western Europe

Finland

Finland underwent severe economic depression in 1990–93. Badly managed financial deregulation of the 1980s, in particular removal of bank borrowing controls and liberation of foreign borrowing, combined with strong currency and a fixed exchange rate policy led to a foreign debt financed boom. Bank borrowing increased at its peak over 100% a year and asset prices skyrocketed. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to a 70% drop in trade with Russia and eventually Finland was forced to devaluate, which increased the private sector's foreign currency denominated debt burden. At the same time authorities tightened bank supervision and prudential regulation, lending dropped by 25% and asset prices halved. Combined with raising savings rate and worldwide economic troubles, this led to a sharp drop of aggregate demand and a wave of bankruptcies. Credit losses mounted and a banking crisis inevitability followed. The number of companies went down by 15%, real GDP contracted about 14% and unemployment rose from 3% to nearly 20% in four years.[22]

Recovery has been based on exports, after currency devaluation of 40% and reviving world economy share of exports as percentage of GDP has risen from 20% to 45%,[23] and Finland has been running consistent current account surpluses. Despite this impressive performance and strong growth mass unemployment has remained a problem.[24]

France

France, just as the rest of continental Europe, entered recession later compared to economies of anglophone countries. The economic climate started to worsen in late 1989 (first in industry) in several phases:[25]

- A progressive slowing of economic activity between late 1989 and Autumn 1990 due mostly to slowing exports (especially to depressed North American markets);

- A sudden slump in the latter part of 1990 as the Gulf War amplified previous tendencies;

- A stand-by situation between mid 1991 and Autumn 1992 as the end of the War in the Gulf provided for some temporary relief;

- Another slump in late 1992 as external demand dries up and the aftermaths of Black Wednesday.[26]

The recession officially starts at the end of 1992 and beginning of the 1993. It is a brief but important recession: GDP drops 0.5% in the last quarter of 1992 and 0.9% in the first quarter of 1993. The drop is amplified by weak exports figures as most of France's trading partners also entered recession at the end of 1992. On a yearly basis, GDP growth was limited to 1.5% in 1992 and –0.9% in 1993, the first negative figure since 1975.[27]

Industry is vastly affected by the recession: output dropped 5.3% in volume in 1993 with a catastrophic first semester and a very limited recovery in the second. The construction industry is also affected by the recession with a 3.9% decrease in volume of output.[28]

All the composants of GDP were depressed in 1993:[28]

- Household consumption recorded its slowest increase in 30 years (+0.4% in volume);

- Investment from both households (residential investments) and enterprises decreased significantly (–4.4 and –6.8% respectively). For the latter early 1993 represents the trough of a slump started in 1990;

- Inventory levels were reduced in 1993;

- Exports decreased (–0.4%) but not as much as imports (–3.1%) meaning that external trade contributed positively to GDP growth in 1993.

The weak economic climate resulted in significant increase in unemployment and public deficits. Reduced activity levels had a direct impact on public finances: social benefits grew 6.8% in 1993 whereas tax revenues only increased 2.4% despite increases in tax rates and charges throughout the year (the Generalized Social Contribution rate was increased by 1.3 points on 1 July 1993).[28]

Sweden

United Kingdom

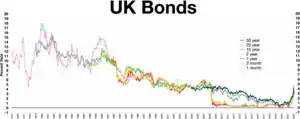

Inverted yield curve 1988-1991

Despite several major economies showing quarterly detraction during 1989, the British economy continued to grow until the third quarter of 1990. Economic growth was not re-established until early 1993, with the end of the recession being officially declared on 26 April that year.[29] The Conservative government which had been in power continuously since 1979 managed to achieve re-election in April 1992 after the replacement of long-serving Margaret Thatcher with John Major as prime minister in November 1990 helped fend off a strong challenge from Neil Kinnock and Labour.

Asian Pacific

Japan

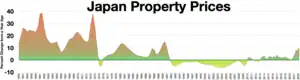

Inverted yield curve in 1990

Zero interest-rate policy starting in 1995

Negative interest rate policy started in 2014

Japan had loose monetary policy in the decades preceding, causing the Japanese asset price bubble. The Bank of Japan raised interest rates to cause an inverted yield curve and reduced M2 money supply increases to tame the property asset bubble. The decade following is known as The Lost Decade.[30]

Political ramifications

Canada and the United States

The Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney in Canada and the successful presidential election campaign of George H. W. Bush in the United States may have been aided by growth in 1988. However, neither leader could hold on to power through the last part of the recession, being challenged by political opponents running on pledges to restore the economy to health. Bush initially enjoyed great popularity after the successful Persian Gulf War, but this soon wore off as the recession worsened; his 1992 re-election bid was particularly hampered by his 1990 decision to renege on his "Read my lips: no new taxes" pledge made during his first campaign in 1988. Meanwhile, Mulroney became deeply unpopular in Canada after two failed constitutional reform attempts (the Meech Lake Accord and Charlottetown Accord) and the 1991 introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). He resigned as prime minister and party leader in 1993, and the Progressive Conservatives collapsed in the election held later that year, winning only two seats.

Australia

In Australia, Paul Keating (then Treasurer of Australia, and future Prime Minister) referred to it as "the recession that Australia had to have".[31] This quote became a cornerstone of the opposition Liberal Party's campaign during the 1993 election, designed to underscore alleged mismanagement of the national economy by the incumbent Labor Party. Unlike the opposition parties in North America, however, the Liberal Party failed to enter government (at least, not until the 1996 election)

New Zealand

In neighbouring New Zealand, the recession came after the re-election of the reformist Lange Labour government. The impact of economic reforms (known as Rogernomics) in the recession led to deep policy divisions between the Prime Minister, David Lange, and the Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas. In response to the recession, Douglas wanted to increase the pace of reform, whereas Lange sought to prevent further reform. Douglas resigned from Cabinet in 1988, but was re-appointed to Cabinet in 1989, prompting Lange to resign. Labour lost the 1990 general elections by a landslide to the National Party, who continued with Douglas' reforms.

France

François Mitterrand was elected to a second term on 8 May 1988 and his political party, the Socialist Party and its allies won a very narrow majority in the National Assembly the next month.

Weakened by the recession and corruption scandals, the Socialist Party suffered severe defeats in the 1992 local elections (regional and cantonal) and the 1993 legislative elections (winning only 53 seats out of 577, its worst turnout until 2017) where the RPR-UDF right-wing coalition were returned to power with a massive majority of 449 seats out of 577.

Influence on culture

In the United States during the recession more people chose to shop at discount stores. This caused Kmart and Walmart (which became the country's largest retailer in 1989) to outsell the traditional stalwart Sears.[32]

Civil unrest

In the United Kingdom, there was a significant wave of rioting at the height of the recession in 1991, with unemployment and social discontent being seen as major factors. Areas affected included Handsworth in Birmingham,[33] Blackbird Leys in Oxford, Kates Hill in Dudley, Meadow Well on Tyneside, Ely in Cardiff and Hartcliffe in Bristol. These were isolated communities devastated by poverty and unemployment, separated from urban centres.[34]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Economic Cycle Research Institute, which considers additional indicators beyond GDP growth and employment, classifies the recession to have begun in March 1990 and ended in March 1992.[9]

References

- ↑ Walsh, Carl (1 February 1993). "What Caused the 1990-1991 Recession?". Economic Review. 2: 33–48 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ "Report" (PDF). bls.gov.

- ↑ "Report" (PDF). bls.gov.

- ↑ "Real Gross Domestic Product". 26 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "GDP growth (annual %) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- 1 2 Statistics Canada (30 May 2018). "Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months". Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months. Government of Canada.

- 1 2 3 Bonham, Mark S."Recession in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cross, Philip, and Bergevin, Philippe "Turning Points: Business Cycles in Canada Since 1926" (PDF). C.D. Howe Institute.

- ↑ "International Business Cycle Dates".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wilson, Thomas, Dungan, Peter, and Murphy, Steve "The Sources of the Recession in Canada: 1989-1992" (PDF), University of Toronto, S2CID 17318693, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2019

- 1 2 3 4 Walsh, Mary Williams "The Hard Times Are Even Harder North of the Border", Los Angeles Times, 24 February 1991

- 1 2 3 4 Kneeboen, Ronald, and Gres, Margarita "Trends, Peaks, and Troughs: National and Regional Employment Cycles in Canada" (PDF). The School of Policy Research Research Papers. University of Calgary. 6 (21). July 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ↑ "How Canada Performs: Unemployment Rate". The Conference Board of Canada. 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Gordon Thiessen, "Canada's Economic Future" What Have We Learned from the 1990s?", Canadian Club of Toronto, January 22, 2001

- ↑ "Canada Prime Rate History | Prime Rate vs. Overnight Rate". 11 July 2023.

- ↑ "Canadian Economic Observer: Historical Statistical Supplement: Table 7.1 — Interest rates and exchange rates".

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and 5.Subjects".

- ↑ Laberge, Yvon (4 December 1992). "27% de la population active de Montréal est sans travail". La Presse (in French). Montreal, Quebec. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- 1 2 "Canada GDP Growth Rate 1961–2020". macrotrends.net.

- ↑ Gordon, Todd, and McCormack, Geoffrey "Canada and the Crisis of Capitalism". Briarpatch. 2020 (March/April).

- ↑ "Finland". Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ www.ek.fi (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20081206133952/http://www.ek.fi/www/fi/talous/tietoa_Suomen_taloudesta/kuvat/tal42.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Tilastokeskus. "Labour Market". www.stat.fi. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ Pollet, Pascale; Lollivier, Stéfan (January 1992). "1989-1991 : ralentissement dans l'industrie" (PDF). Insee Première (in French). Insee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ↑ Éric Chaney; Fabrice Lenseigne; Patrick Pétour (March 1994). "Note de conjoncture de mars 1994 : Le creux du cycle" (PDF). Note de Conjoncture (in French). Insee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- ↑ "En 1993, une récession comparable à celle prévue pour 2009". L'Obs. 19 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 Magali Demotes-Mainard (April 1994). "Les Comptes de la Nation en 1993" (PDF). Insee Première (in French). Insee (309). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- ↑ "1993: Recession over - it's official". 26 April 1993 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "The Lost Decade: Lessons from Japan's Real Estate Crisis".

- ↑ Paul Keating – Chronology Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine at australianpolitics.com

- ↑ "Gainesville Sun - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ↑ "Police clash with rioting youths in England, Wales". Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "A History of British Rioting". Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.