The economy of Austria-Hungary changed slowly during the existence of the Dual Monarchy, 1867-1918. The capitalist way of production spread throughout the Empire during its 50-year existence replacing medieval institutions. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda (Ancient Buda) merged with the third city, Pest, thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. The dynamic Pest grew into Hungary's administrative, political, economic, trade and cultural hub. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period.

Austria-Hungary was a large, heavily rural country with wealth and income levels a bit below the European average. Growth rates were similar to Europe as a whole. After 1895. migration became a major factor, with most headed to the United States.

Background

The Habsburg realms included 23 million inhabitants in 1800, growing to 36 million by 1870, third in population size behind Russia and Germany.[1] Nationally the per capita rate of industrial growth averaged about 3% between 1818 and 1870. However there were strong regional differences. That was relatively little international trade. In the Alpine and Bohemian regions, proto-industrialization at begun by 1750, and became the center of the first phases of the industrial revolution after 1800. The textile industry was the main factor, utilizing mechanization, steam engines, and the factory system. Much of machinery was purchased from the British. In the Bohemian regions, machine spinning started later and only became a major factor by 1840. Bohemia's resources were successfully exploited, growing 10% a year. The iron industry had developed in the Alpine regions after 1750, with smaller centers in Bohemia and Moravia. Key factors included the replacement of charcoal by coal, introduction of steam engine, and the rolling regard. The first steam engine appeared in 1816 but the abundance of water power slowed its dissemination. Hungary was heavily rural with little industry before 1870.[2][3] The first machine building factories appeared in the 1840s.

Economic trends 1870-1913

Technological change accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The GNP per capita grew roughly 1.76% per year from 1870–1913. That level of growth compared very favorably to that of other European nations such as Britain (1%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%).[4] However, in a comparison with Germany and Britain: the Austro-Hungarian economy as a whole still lagged considerably, as sustained modernization had begun much later.

By 1913, the population of Austria-Hungary was 48 million, compared to 171 million in Russia, 67 million in Germany, 40 million in France, and 35 million in Italy, as well as 98 million in the United States. The population was heavily rural, with 67% of the workforce in agriculture in 1870, and 60% in 1913. They concentrated in grain production, not livestock. Only 16% of the workforce was employed by industry in 1870, rising to 22%. The output of coal, iron and beer was comparable to Belgium, which had only one sixth the population.[5]

Foreign investment in the Empire, 1870 to 1913, was dominated by Germany, followed by France, and to a lesser extent Great Britain. However Austria exported more capital than it imported. Foreign trade during this period, imports plus exports, averaged about a fourth of Austria's GNP. To protect its growing industries, Vienna raised tariffs in the 1870s and 1880s . As a result economic growth was strong as the GNP doubled from 1870 to 1913. Austria-Hungary grew by 93%, compared to growth of 115% for the remainder of Europe. Per capita growth of wealth was slightly higher than the rest of Europe.[6]

Geographical variation

Economic growth centered on Vienna, Budapest and Prague, as well as the Austrian lands (areas of modern Austria), the Alpine region and the Bohemian lands. In the later years of the 19th century, rapid economic growth spread to the central Hungarian plain and to the Carpathian lands. As a result, wide disparities of development existed within the Empire. In general, the western areas became more developed than the eastern.

By the end of the 19th century, economic differences gradually began to even out as economic growth in the eastern parts of the Empire consistently surpassed that in the western. The Empire built up the fourth-largest machine building industry of the world, after the United States, Germany, and Great Britain.[7] Austria-Hungary was also the world's third largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances and facilities for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire.[8][9]

The strong agriculture and food industry of Hungary with its center at Budapest became predominant within the Empire and made up a large proportion of the export to the rest of Europe. Meanwhile, western areas, concentrated mainly around Prague and Vienna, excelled in various manufacturing industries. However, since the turn of the twentieth century, the Austrian half of the Empire could preserve its dominance within the empire in the sectors of the first industrial revolution, but Hungary had a better position in the industries of the second industrial revolution, in these modern sectors of the second industrial revolution the Austrian competition could not become dominant.[10] This division of labour between the east and west, besides the existing economic and monetary union, led to an even more rapid economic growth throughout Austria-Hungary by the early 20th century. The most important trading partner was Germany (1910: 48% of all exports, 39% of all imports), followed by Great Britain (1910: almost 10% of all exports, 8% of all imports). Trade with the geographically neighboring Russia, however, had a relatively low weight (1910: 3% of all exports /mainly machinery for Russia, 7% of all imports /mainly raw materials from Russia). In the Galician north, the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, an ethnic Pole-administered autonomous unit under the Austrian crown, became the major oil-producing region of Europe.[11][12][13][14]

Trade

From 1527 (the creation of the monarchic personal union) to 1851, the Kingdom of Hungary maintained its own customs controls, which separated it from the other parts of the Habsburg-ruled territories.[15] After 1867, the Austrian and Hungarian customs union agreement had to be renegotiated and stipulated every ten years. The agreements were renewed and signed by Vienna and Budapest at the end of every decade because both countries hoped to derive mutual economic benefit from the customs union. The Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary contracted their foreign commercial treaties independently of each other.[16]

Industry

The empire's heavy industry had mostly focused on machine building, especially for the electric power industry, locomotive industry and automotive industry, while in light industry the precision mechanics industry was the most dominant. Through the years leading up to World War I the country became the 4th biggest machine manufacturer in the world.[17]

The two most important trading partners were traditionally Germany (1910: 48% of all exports, 39% of all imports), and Great Britain (1910: almost 10% of all exports, 8% of all imports), the third most important partner was the United States, it followed by Russia, France, Switzerland, Romania, the Balkan states and South America.[16] Trade with the geographically neighbouring Russia, however, had a relatively low weight (1910: 3% of all exports /mainly machinery for Russia, 7% of all imports /mainly raw materials from Russia).

Rolling stock and rail

The factories producing rolling stock such as locomotives, steam engines and wagons, but also bridges and other iron structures, were installed in Vienna (Locomotive Factory of the State Railway Company, founded in 1839), in Wiener Neustadt (New Vienna Locomotive Factory, founded in 1841), and in Floridsdorf (Floridsdorf Locomotive Factory, founded in 1869).[18][19][20]

The Hungarian factories producing rolling stock as well as bridges and other iron structures were the MÁVAG company in Budapest (steam engines and wagons) and the Ganz company in Budapest (steam engines, wagons, the production of electric locomotives and electric trams started from 1894).[21] and the RÁBA Company in Győr.

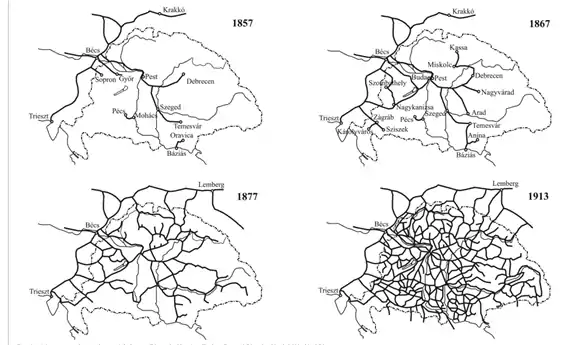

The Austro-Hungarian Empire realized it needed railways for it had a large population and large territory where travel was difficult. It needed long lines to coastal ports on the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea. The railway system was built for light duty traffic. The system provided a local demand for iron and steel, coal, rolling stock, terminals, yards, construction projects, skilled workers and manual labor. Although much of the engineering expertise was imported, most of the labor and materials were provided by the empire itself. When Austria and Hungary united in 1867, 6000 km of lines had been built, chiefly in the more industrialized Austria. Quickly all the major cities were linked together by 7600 km of new lines. This promoted rapid industrialization around Vienna, Bohemia, and Silesia. The worldwide economic panic of 1873 ended the construction boom. After 1880 three-fourths of the lines were nationalized. The Orient Express from Vienna to Constantinople was a prestige line, but added little to the economy. After 1900 a new major factor was outward emigration – over 2 million left for the United States in 1900-1914. By 1914 43,280 km were in operation, exceeded in length only by Russia and Germany.[22]

Although of lighter weight and not as well-managed as the German lines, the Austro-Hungarian system played a major role in supporting the Army in the First World War. Half of the rolling stock was reserved for the Army, and the rest was being run down and cannibalized. The system was in virtual collapse by 1918, as the cities ran short of food and coal.[23]

Regions

- Austria: see Rail transport in Austria and Austrian Federal Railways

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: see Rail transport in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Croatia: see Croatian Railways

- Czech Republic: see Rail transport in the Czech Republic and České dráhy

- Hungary: see Hungarian State Railways

- Poland: see Rail transport in Poland and PKP

- Slovakia: see Rail transport in Slovakia

- Slovenia: see Rail transport in Slovenia

Automotive industry

Prior to World War I, the Austrian Empire had five car manufacturer companies. These were: Austro-Daimler in Wiener-Neustadt (cars trucks, buses),[24] Gräf & Stift in Vienna (cars),[25] Laurin & Klement in Mladá Boleslav (motorcycles, cars),[26] Nesselsdorfer in Nesselsdorf (Kopřivnice), Moravia (automobiles), and Lohner-Werke in Vienna (cars).[27] Austrian car production started in 1897.

Prior to World War I, the Kingdom of Hungary had four car manufacturer companies. These were: the Ganz company[28][29] in Budapest, RÁBA Automobile[30] in Győr, MÁG (later Magomobil)[31][32] in Budapest, and MARTA (Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad)[33] in Arad. Hungarian car production started in 1900. Automotive factories in the Kingdom of Hungary manufactured motorcycles, cars, taxicabs, trucks and buses.

Electrical industry and electronics

In 1884, Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy and Miksa Déri (ZBD), three engineers associated with the Ganz Works of Budapest, determined that open-core devices were impractical, as they were incapable of reliably regulating voltage.[34] When employed in parallel connected electric distribution systems, closed-core transformers finally made it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces.[35][36] The other essential milestone was the introduction of 'voltage source, voltage intensive' (VSVI) systems'[37] by the invention of constant voltage generators in 1885.[38] Bláthy had suggested the use of closed cores, Zipernowsky had suggested the use of parallel shunt connections, and Déri had performed the experiments;[39]

The first Hungarian water turbine was designed by the engineers of the Ganz Works in 1866, the mass production with dynamo generators started in 1883.[40] The manufacturing of steam turbo generators started in the Ganz Works in 1903.

In 1905, the Láng Machine Factory company also started the production of steam turbines for alternators.[41]

Tungsram is a Hungarian manufacturer of light bulbs and vacuum tubes since 1896. On 13 December 1904, Hungarian Sándor Just and Croatian Franjo Hanaman were granted a Hungarian patent (No. 34541) for the world's first tungsten filament lamp. The tungsten filament lasted longer and gave brighter light than the traditional carbon filament. Tungsten filament lamps were first marketed by the Hungarian company Tungsram in 1904. This type is often called Tungsram-bulbs in many European countries.[42]

Despite the long experimentation with vacuum tubes at Tungsram company, the mass production of radio tubes begun during WW1,[43] and the production of X-ray tubes started also during the WW1 in Tungsram Company.[44]

The Orion Electronics was founded in 1913. Its main profiles were the production of electrical switches, sockets, wires, incandescent lamps, electric fans, electric kettles, and various household electronics.

The telephone exchange was an idea of the Hungarian engineer Tivadar Puskás (1844–1893) in 1876, while he was working for Thomas Edison on a telegraph exchange.[45][46][47][48][49]

The first Hungarian telephone factory (Factory for Telephone Apparatuses) was founded by János Neuhold in Budapest in 1879, which produced telephones microphones, telegraphs, and telephone exchanges.[50][51][52]

In 1884, the Tungsram company also started to produce microphones, telephone apparatuses, telephone switchboards and cables.[53]

The Ericsson company also established a factory for telephones and switchboards in Budapest in 1911.[54]

Aeronautic industry

The first airplane in Austria was Edvard Rusjan's design, the Eda I, which had its maiden flight in the vicinity of Gorizia on 25 November 1909.[55]

The first Hungarian hydrogen-filled experimental balloons were built by István Szabik and József Domin in 1784. The first Hungarian designed and produced airplane (powered by a Hungarian built inline engine) was flown at Rákosmező on 4 November[56] 1909.[57] The earliest Hungarian airplane with Hungarian built radial engine was flown in 1913. Between 1912 and 1918, the Hungarian aircraft industry began developing. The three greatest: UFAG Hungarian Aircraft Factory (1914), Hungarian General Aircraft Factory (1916), Hungarian Lloyd Aircraft, Engine Factory at Aszód (1916),[58] and Marta in Arad (1914).[59] During the First World War, fighter planes, bombers and reconnaissance planes were produced in these factories. The most important aero-engine factories were Weiss Manfred Works, GANZ Works, and Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad.

Shipbuilding

The largest shipyard in the dual monarchy and a strategic asset for the Austro-Hungarian Navy was the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino in Trieste, founded in 1857 by Wilhelm Strudthoff. Second in importance was the Danubius Werft in Fiume (present-day Rijeka, Croatia). Third in importance for the naval shipbuilding was the Navy's own Marinearsenal, located at the main naval base in Pola, present-day Croatia. Smaller shipyards included the Cantiere Navale Triestino in Monfalcone (established in 1908 with ship repairs as the main activity, but went on during the war to manufacture submarines) and the Whitehead & Co. in Fiume. The latter was established in 1854 under the name Stabilimento Tecnico Fiume with Robert Whitehead as the enterprise's director and the purpose to produce his torpedoes for the Navy. The company went bankrupt in 1874 and in the following year Whitehead bought it to establish the Whitehead & Co. Next to torpedoes the company went on to produce submarines during WWI. On the Danube, the DDSG had established the Óbuda Shipyard on the Hungarian Hajógyári Island in 1835.[60] The largest Hungarian shipbuilding company was the Ganz-Danubius.

References

- ↑ "Population of the Major European Countries in millions".

- ↑ Martin Moll, "Austria-Hungary" in Christine Rider, ed., Encyclopedia of the Age of the Industrial Revolution 1700–1920 (2007) pp 24-27.

- ↑ Millward and Saul, The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850-1914 pp 271–331.

- ↑ Good, David. The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire

- ↑ Stephen Bradberry and Kevin O'Rourke, eds, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe volume 2: 1870 to the present (2010) pp. 34, 61, 65, 75, 76.

- ↑ Cambridge economic history of modern Europe 2:8, 12, 22, 36.

- ↑ Schulze, Max-Stephan. Engineering and Economic Growth: The Development of Austria-Hungary's Machine-Building Industry in the Late Nineteenth Century, p. 295. Peter Lang (Frankfurt), 1996.

- ↑ The Publisher. Vol. 133. 1930. p. 355.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Österreichische konsularische Vertretungsbehörden im Ausland New York (1965). Austrian information. p. 17.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Berend, Iván T. (2013). Case Studies on Modern European Economy: Entrepreneurship, Inventions, and Institutions. Routledge. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-135-91768-5.

- ↑ Schatzker, Valerie; Erdheim, Claudia; Sharontitle, Alexander. "Petroleum in Galicia". Drohobycz Administrative District: History. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ Golonka, Jan; Picha, Frank J. (2006). The Carpathians and Their Foreland: Geology and Hydrocarbon Resources. American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG). ISBN 978-0-89181-365-1.

- ↑ Frank, Allison (June 29, 2006). "Galician California, Galician Hell: The Peril and Promise of Oil Production in Austria-Hungary". Washington, D.C.: Office of Science and Technology Austria (OSTA). Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ Schwarz, Robert (1930). Petroleum-Vademecum: International Petroleum Tables (VII ed.). Berlin and Vienna: Verlag für Fachliteratur. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Richard L. Rudolph: Banking and Industrialization in Austria–Hungary: The Role of Banks in the Industrialization of the Czech Crownlands, 1873–1914, Cambridge University Press, 2008 (page 17)

- 1 2 Headlam, James Wycliffe (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–39.

- ↑ Max-Stephan Schulze (1996). Engineering and Economic Growth: The Development of Austria–Hungary's Machine-Building Industry in the Late Nineteenth Century. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 295.

- ↑ "velocipedes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Czechoslovak Foreign Trade, Volume 29. Rapid, Czechoslovak Advertising Agency. 1989. p. 6.

- ↑ Iron Age, Volume 85, Issue 1. Chilton Company. 1910. pp. 724–725.

- ↑ "Hipo Hipo – Kálmán Kandó(1869–1931)". Sztnh.gov.hu. 29 January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Alan Milward, and S. B. Saul, The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850–1914 (1977) pp 302–304.

- ↑ Clifford F. Wargelin, "The economic collapse of Austro-Hungarian dualism, 1914-1918." East European Quarterly 34.3 (2000): 263.

- ↑ Erik Eckermann: World History of the Automobile – Page 325

- ↑ Hans Seper: Die Brüder Gräf: Geschichte der Gräf & Stift-Automobile

- ↑ "Václav Laurin a Václav Klement" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 1 June 2004.

- ↑ Kurt Bauer (2003), Faszination des Fahrens: unterwegs mit Fahrrad, Motorrad und Automobil (in German), Böhlau Verlag Wien, Kleine Enzyklopädie des Fahrens, "Lohner", pp. 250–1

- ↑ Iván Boldizsár: NHQ; the New Hungarian Quarterly – Volume 16, Issue 2; Volume 16, Issues 59–60 – Page 128

- ↑ Hungarian Technical Abstracts: Magyar Műszaki Lapszemle – Volumes 10–13 – Page 41

- ↑ Joseph H. Wherry: Automobiles of the World: The Story of the Development of the Automobile, with Many Rare Illustrations from a Score of Nations (Page:443)

- ↑ "The history of the biggest pre-War Hungarian car maker". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ Commerce Reports Volume 4, page 223 (printed in 1927)

- ↑ G.N. Georgano: The New Encyclopedia of Motorcars, 1885 to the Present. S. 59.

- ↑ Hughes, Thomas P. (1993). Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8018-2873-2.

- ↑ "Bláthy, Ottó Titusz (1860–1939)". Hungarian Patent Office. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2004.

- ↑ Zipernowsky, K.; Déri, M.; Bláthy, O.T. "Induction Coil" (PDF). U.S. Patent 352 105, issued 2 Nov. 1886. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ American Society for Engineering Education. Conference – 1995: Annual Conference Proceedings, Volume 2, p. 1848.

- ↑ Hughes (1993), p. 96.

- ↑ Smil, Vaclav (2005). Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867–1914 and Their Lasting Impact. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-198-03774-3.

ZBD transformer.

- ↑ "Vízenergia hasznosítás szigetközi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ↑ United States. Congress (1910). Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 41, 53.

- ↑ "GE Lighting: Rövid történet – A Short History" (PDF). General Electric. 30 May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2005. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ↑ See: The History of Tungsram 1896–1945" Page: 32

- ↑ See: The History of Tungsram 1896–1945" Page: 33

- ↑ Alvin K. Benson (2010). Inventors and inventions Great lives from history Volume 4 of Great Lives from History: Inventors & Inventions. Salem Press. p. 1298. ISBN 978-1-587-65522-7.

- ↑ Puskás Tivadar (1844 - 1893) (short biography), Hungarian History website. Retrieved from Archive.org, February 2013.

- ↑ "Puskás Tivadar (1844–1893)". Mszh.hu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ↑ "Puskás, Tivadar". Omikk.bme.hu. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ↑ "Welcome hunreal.com - BlueHost.com". Hunreal.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ↑ E und M: Elektrotechnik und Maschinenbau. Volume 24. page 658.

- ↑ Eötvös Loránd Matematikai és Fizikai Társulat Matematikai és fizikai lapok. Volumes 39–41. 1932. Publisher: Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ Contributor Budapesti Történeti Múzeum: Title: Tanulmányok Budapest múltjából. Volume 18. page 310. Publisher Budapesti Történeti Múzeum, 1971.

- ↑ Károly Jeney; Ferenc Gáspár (1990). The History of Tungsram 1896–1945 (PDF). Translated by Erwin Dunay. Tungsram Rt. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-939-19729-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ↑ IBP, Inc. (2015). Hungary Investment and Business Guide (Volume 1) Strategic and Practical Information World Business and Investment Library. lulu. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-514-52857-0.

- ↑ "Edvard Rusjan, Pioneer of Slovene Aviation". Republic of Slovenia – Government Communication Office. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ ""Aircraft"(in Hungarian)". mek.oszk.hu. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ↑ The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA): History of Flight from Around the World Archived 4 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine: Hungary article.

- ↑ "Mária Kovács: Short History of Hungarian Aviation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Péter, Puskel. "Az aradi autógyártás sikertörténetéből". NyugatiJelen.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Victor-L. Tapie, The Rise and Fall of the Habsburg Monarchy p. 267

Further reading

- Caruana-Galizia, Paul, and Jordi Martí-Henneberg. "European regional railways and real income, 1870–1910: a preliminary report." Scandinavian Economic History Review 61.2 (2013): 167-196. online

- Cipolla, Carlo M., ed. (1973). The Emergence of Industrial Societies vol 4 part 1. Glasgow: Fontana Economic History of Europe. pp. 228–278. online

- Evans, Ifor L. "Economic Aspects of Dualism in Austria-Hungary." Slavonic and East European Review 6.18 (1928): 529-542.

- Good, David. The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire (1984) excerpt

- Good, David F. "Austria-Hungary." in Patterns of European Industrialisation: The nineteenth century ed by R. Sylla, and G. Toniolo. (1991): 218-247. excerpt

- Good, D. F. "The Great Depression and Austrian Growth after 1873" Economic History Review (1978) 31: 290–4.

- Good, David F. "The economic lag of central and eastern Europe: income estimates for the Habsburg successor States, 1870-1910." Journal of Economic history (1994): 869-891 online.

- Good, David F. "Uneven development in the nineteenth century: a comparison of the Habsburg Empire and the United States." Journal of Economic History (1986): 137-151 online.

- Grimm, Richard. "The Austro-German Relationship." Journal of European Economic History 21.1 (1992): 111–120, online.

- Katus, L. "Economic growth in Hungary during the age of Dualism (1867-1913): A quantitative analysis" in E. Pamlényi (ed.), Sozialökonomische Forschungen zur Geschichte Ost-Mitteleuropas (1970), pp. 35–127.

- Komlos, John. The Habsburg Monarchy as a Customs Union: Economic Development in Austria-Hungary in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton UP, 1983).

- Milward, Alan, and S. B. Saul. The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850-1914 (1977) pp 271–331. online

- Roman, Eric. Austria-Hungary & the Successor States: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present (2003), 699pp online

- Rudolph, Richard L. Banking and Industrialization in Austria-Hungary: The role of banks in the industrialization of the Czech Crownlands, 1873-1914 (Cambridge UP, 1977). online

- Schulze, Max-Stephan. "Origins of catch-up failure: comparative productivity growth in the Habsburg Empire, 1870–1910." European Review of Economic History 11.2 (2007): 189-218 online.

- Schulze, Max-Stephan. "Austria-Hungary's Economy in World War I." in The Economics of World War I ed. by Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison. (2005) pp 92+.

- Schulze, M.S. "The machine-building industry and Austria's great Depression after 1873" Economic History Review (1997), 50#2 pp. 282–304.

- Turnock, David. The economy of East Central Europe, 1815-1989: stages of transformation in a peripheral region (Routledge, 2004).

- Turnock, David. Eastern Europe: An Historical Geography 1815-1945 (1988) online

- Wargelin, Clifford F. "The economic collapse of Austro-Hungarian dualism, 1914-1918." East European Quarterly 34.3 (2000): 261–280, online.