_(14781747542).jpg.webp)

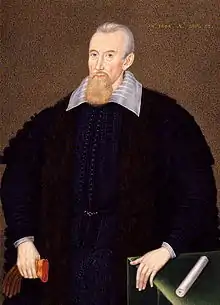

Edward Bruce, 1st Lord Kinloss PC (1548 – 14 January 1611) was a Scottish lawyer and judge.[1]

.svg.png.webp)

He was the second son of Edward Bruce of Blairhall and Alison Reid.

Career

In 1594 James VI sent him as ambassador to London and gave him £1,000 Scots for his expenses.[2] With James Colville, he was sent to invite Queen Elizabeth to send a representative to the baptism of Prince Henry, discuss the matter of the Earl of Bothwell, Catholics in Scotland, and ask for the yearly sum of money that Elizabeth gave to James VI. They were to ensure the money was paid to Thomas Foulis. He also requested the rendition of Anne of Denmark's goldsmith Jacob Kroger who had fled to England with the queen's jewels.[3]

Bruce was sent to London for money from Elizabeth again in April 1598 and received £3,000.[4] He interceded in a legal case in London for his brother, George Bruce of Carnock, whose ship the Bruce had been forced to take on a group of African and Portuguese captives by English captains.[5] He also successfully negotiated the release of Robert Ker of Cessford who was held by the Archbishop of York at Bishopthorpe.[6] On his return to Edinburgh, Bruce met with James VI in his cabinet at Holyrood Palace for four hours.[7]

He was made Commendator of the Abbey of Kinloss in 1601 and became Baron of Muirton. He served as a Lord of Session from 1597 to 1603 and was created Lord Kinloss in 1602, with remainder to his heirs and assigns whatsoever.

After the embassy of the Earl of Mar and Bruce to London in April 1601 the sum paid as a subsidy to James VI was increased, by the persuasion of Sir Robert Cecil.[8] Bruce was involved in the "Secret correspondence of James VI", an initiative to help put James on the throne of England.[9]

He accompanied the King to England on his accession in 1603. In June the king sent him to greet Charles of Arenberg, who had arrived as the envoy from Isabella and Albert Rulers of the Netherlands to congratulate James, but had fallen ill from gout.[10]

Bruce became an English subject, was admitted to the Privy Council, and appointed Master of the Rolls for life. He also received Whorlton Castle and its manor in 1603, which would remained in the Bruce family until the late 19th century.[1]

In 1604, he was made Lord Bruce of Kinloss, with remainder to his heirs male. A letter from the Earl of Salisbury to the Earl of Shrewsbury written in 1608 alludes to Bruce having a grave illness.[11]

He died in London in January 1611. He was succeeded in his titles by his eldest son, also named, Edward Bruce.[1]

An inventory was made of his household goods and silverware around the year 1610. He had seven pieces of tapestry for his great chamber, and a suite of gilt leather hangings for the gallery. His pictures included the king's arms, a portrait of Christian IV of Denmark, a Queen of Persia, a Queen of Turkey, Paris and Helen, a portrait of a nun, and a portrait of a French woman.[12]

Marriage and children

Edward Bruce married Magdalene Clerk, daughter of Alexander Clerk. Their children included:

- Edward Bruce, 2nd Lord Kinloss (1594–1613), who was killed in duel with Edward Sackville at Bergen-op-Zoom and buried there, except his heart which was buried at Culross Abbey in a heart-shaped silver case clamped with iron between two stones. The heart burial was discovered in 1808 and reburied.[13]

- Christian Bruce (died 1675), who married William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire.[14]

- Thomas Bruce, 1st Earl of Elgin (1599–1663)

- Robert Bruce, Baron of Skelton[15]

- Janet Bruce (who may have been born illegitimately to another mother),[1] who married Thomas Dalyell of the Binns, and was the mother of General Tam Dalyell of the Binns.

After his death, his widow married secondly Sir James Fullerton, MP and courtier, in 1616.[1] William Gouge dedicated his book A Guide to Goe to God to her and Sir James.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Balfour Paul, James (1904). The Scots Peerage. Edinburgh : D. Douglas. pp. 474-476. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588-1596', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 79

- ↑ Annie I. Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1593-1595, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 312–4, 344.

- ↑ Julian Goodare, 'James VI's English Subsidy', Julian Goodare & Michael Lynch, Reign of James VI (Tuckwell: East Linton, 2000), p. 115.

- ↑ John Duncan Mackie, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1597-1603, 13.1 (Edinburgh, 1969), pp. 186–7, 194–5, 297, 309, 343, 345–7.

- ↑ John Strype, Annals of the Reformation, vol. 4 (London, 1824), pp. 447–8.

- ↑ Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1597-1603, 13.1 (Edinburgh, 1969), pp. 200–4, 206.

- ↑ Alexander Courtney, 'The Secret Correspondence of James VI, 1601-3', in Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, Doubtful and dangerous: The question of the succession in late Elizabethan England (Manchester, 2014), pp. 138-9: Julian Goodare (2000), pp. 113, 166.

- ↑ Alexander Courtney, 'The Secret Correspondence of James VI, 1601-3', Susan Doran & Paulina Kewes, Doubtful and dangerous: The question of the succession in late Elizabethan England (Manchester, 2014), p. 139.

- ↑ Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 3 (London, 1838), p. 15.

- ↑ Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 3 (London, 1838), p. 247.

- ↑ Ferrerii Historia abbatum de Kynlos: una cum vita Thomae Chrystalli abbatis (Edinburgh, 1839), pp. xi-xii.

- ↑ Lord Stowell, 'Account of the Discovery of the Heart of Lord Edward Bruce at Culross in Perthshire', Archaeologia, vol. 20 (London, 1824), pp. 515–8.

- ↑ Lawrence Stone, Crisis of the Aristocracy (Oxford, 1965), p. 658.

- ↑ Weeks, Lyman Horace (1907). Book of Bruce; ancestors and descendants of King Robert of Scotland. New York: The Americana Society.

- ↑ Smuts, R. Malcolm (2016). The Oxford Handbook of the Age of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. p. 773. ISBN 9780191074172. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)