Edward Clarke Cabot | |

|---|---|

Edward Clarke Cabot, was an American architect and artist. | |

| Born | April 17, 1818 |

| Died | January 5, 1901 (aged 82) |

| Occupation(s) | Architect, artist |

| Spouses | Martha Eunice Robinson

(m. 1842)Louisa Winslow Sewall

(m. 1873) |

| Parent(s) | Samuel Cabot Jr. Eliza Perkins Cabot |

Edward Clarke Cabot (August 17, 1818 – January 5, 1901) was an American architect and artist.

Life and career

Edward Clarke Cabot was born April 17, 1818, in Boston, Massachusetts to Samuel Cabot Jr. and Eliza (Perkins) Cabot. He was the third of their seven children. He was educated in private schools in Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts. Cabot was self-taught as an artist and did not attend college. At the age of 17, in about 1835, Cabot went west to Cairo, Illinois to raise sheep. This venture faltered and failed about 1840. In 1842, Cabot returned east and moved to Windsor, Vermont, where he again raised sheep. When in 1846 the Boston Athenaeum solicited for plans for its new building, Cabot submitted a proposal. His design was selected by the trustees with the condition that Cabot associate himself with George Minot Dexter, an experienced architect and engineer, to execute the design. The Athenaeum design, influenced by the contemporary English work of Charles Barry, was begun in 1847 and completed in 1849. Once construction was complete, Cabot established himself as an architect in Boston. To handle the business of architecture, he formed a partnership with his younger brother, James Elliot Cabot. They were associated from 1849 to 1858 and again from 1862 to 1865. He otherwise practiced independently until 1875 when he formed a new partnership with Francis Ward Chandler, known as Cabot & Chandler.[1] They worked together until 1888, when Chandler was appointed director of the department of architecture of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cabot then formed a new partnership with two of his assistants, Arthur Greene Everett and Samuel W. Mead.[2] Cabot soon retired from Cabot, Everett & Mead, but his name remained associated with the firm until his death in 1901.[1] His partners continued the business as Everett & Mead for several years.

When the Boston Society of Architects was organized in 1867, Cabot was elected the first president. He continued to fill this office until 1896, when he declined to be renominated.[1]

After the opening of the Boston Athenaeum, he became a leading figure in Boston architectural circles. Cabot designed the Gibson House for widow Catherine Hammond Gibson and her son Charles Hammond Gibson Jr. He is also noted for producing several distinguished Queen Anne Style houses in the 1870s. As a member of Cabot & Chandler, Cabot built numerous residences in the Back Bay and Boston environs. In 1879, Cabot & Chandler responded to H. H. Richardson's introduction of the Stick Style of Architecture into the U. S. by his Watts Sherman House in Newport, with Cabot's splendid mansion for Elbridge Torrey at 1 Melville Avenue in Dorchester, MA. The same year the firm designed 12 Fairfield Street in Boston's Back Bay for Georgiani Lowell.[3]

Personal life

Cabot was twice married. He married first in 1842, to Martha Eunice Robinson (born December 9, 1818; died November 28, 1871) of Salem, Massachusetts. She died at home in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1871. He married second in 1873 to Louisa Winslow Sewall (born June 3, 1846; died August 10, 1907) of Roxbury, Massachusetts. With his first wife he had five children: Thomas Handasyd (born April 1, 1843; died June 13, 1843), Martha Robinson (born May 27, 1844), Elizabeth Perkins (born January 6, 1847; died May 11, 1865), William Robinson (born November 11, 1853) and George Edward (born February 22, 1861). With his second wife he had three additional children: Sewall (born March 8, 1875), Norman Winslow (born July 1, 1876) and Lucy Sewall (born February 17, 1890).[1]

His second son, William Robinson Cabot, was educated as an architect and would practice in partnership with Richard Clipston Sturgis from 1888 to 1895.[4] His youngest son, Norman Winslow Cabot, would become noted as a football player.[5]

Cabot enlisted in the Union Army on September 12, 1862, with the 44th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which saw action during the Civil War. This regiment was mustered out on June 18, 1863.[1]

Before building his own home, Cabot variously lived on Pinckney Street in Boston, Adams Street in Milton and his grandfather's estate in Brookline. In 1865, he bought property at the corner of High Street and Chestnut Street in Brookline, where he built a house. In 1881, he subdivided the land and sold his old house, building a new house on the remainder of the land. He lived in the latter house until his death. Neither is still standing. In later life he also owned a summer home at Nonquitt in Dartmouth, Massachusetts.[1]

After his retirement from practice, Cabot focused on painting.[1]

Cabot died January 5, 1901, at home in Brookline, Massachusetts at the age of 82.[1]

Architectural works

- Boston Athenaeum, Boston, Massachusetts (1847–49, NRHP 1966)[1]

- Freeman Place Chapel, Boston, Massachusetts (1847–48, demolished)[6]

- First Parish Church (former), Brookline, Massachusetts (1848, demolished 1891)[7]

- "Holmesdale" for Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1849)[8]

- House for Samuel Cabot Jr., Brookline, Massachusetts (1849)[9]

- Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, Massachusetts (1849, demolished)[10]

- House for Charles Larkin, Milton, Massachusetts (1852)[11]

- House for Thomas Handasyd Perkins, Nahant, Massachusetts (1853)[12]

- House for John Murray Forbes, Milton, Massachusetts (1853)[13]

- Boston Theatre, Boston, Massachusetts (1854, demolished)[14]

- Richards Block, Boston, Massachusetts (1858)[15]

- Harvard Gymnasium, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1859–60, demolished 1933)[16]

- Houses for Samuel Hammond Russell and Catherine (Hammond) Gibson, Boston, Massachusetts (1859–60)

- President's House, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1860, demolished)[17]

- Stone Library at "Peacefield" for Charles Francis Adams Sr., Quincy, Massachusetts (1869–70)[18]

- "Morningside" for William Barton Rogers, Newport, Rhode Island (1871)[19]

- House for Walter Channing Cabot,[lower-alpha 1] Brookline, Massachusetts (1873, demolished)[20]

- Johns Hopkins Hospital,[lower-alpha 2] Baltimore, Maryland (1877–89)[21]

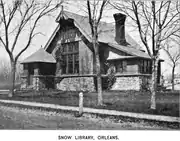

- Snow Library, Orleans, Massachusetts (1877–78, burned 1952)[22]

- House for Georgiana Lowell, Boston, Massachusetts (1879)[15]

- House for Thomas Sergeant Perry, Boston, Massachusetts (1879)[23]

- Merrill Hall, Doane University, Crete, Nebraska (1879, burned 1969)[24]

- House for Elbridge Torrey, Dorchester, Boston, Massachusetts (1880, demolished)[25]

- Insurance Company of North America Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1880, demolished)[26]

- House for Samuel Cabot III, Brookline, Massachusetts (1881)[27]

- Brown Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1882, demolished)[28]

- House for Francis Ward Chandler, Boston, Massachusetts (1883–84)[29]

- Gaylord Hall, Doane University, Crete, Nebraska (1884)[24]

- House for John Torrey Morse, Boston, Massachusetts (1884–85, demolished)[30]

- Hotel Florence, Bar Harbor, Maine (1887, burned 1917)[31]

- House for Louis Cabot, Dublin, New Hampshire (1887, NRHP 1983)[32]

- House for Lois Lillie (White) Howe, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1887, NRHP 1983)[33]

- Walter Hastings Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1888)[17]

Gallery of architectural works

Boston Athenaeum, Boston, Massachusetts, 1847-49.

Boston Athenaeum, Boston, Massachusetts, 1847-49. Interior of the Freeman Place Chapel, Boston, Massachusetts, 1847-48.

Interior of the Freeman Place Chapel, Boston, Massachusetts, 1847-48.

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, 1877-89.

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, 1877-89. Snow Library, Orleans, Massachusetts, 1877-78.

Snow Library, Orleans, Massachusetts, 1877-78. Gaylord Hall, Doane University, Crete, Nebraska, 1884.

Gaylord Hall, Doane University, Crete, Nebraska, 1884.

Notes

- ↑ The home of one of Cabot's brothers. Located on Heath Street, directly below the Single Tree Hill Reservoir.

- ↑ Designed in association with Baltimore architect John Rudolph Niernsee.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 L. Vernon Briggs, History and Genealogy of the Cabot Family, 1475-1927, vol. 2 (Boston: Charles E. Goodspeed & Company), 1927, p.690

- ↑ "Personal," Building 8, no. 23 (June 9, 1888):

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 880. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

- ↑ "Personal," Engineering and Building Record 18, no. 1 (June 2, 1888): 10.

- ↑ Harvard College Class of 1898 Quindecennial Report. Harvard University. 1913. p. 51. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ James Freeman Clarke, A Discourse Delivered at the Dedication of the Chapel, built by the Church of the Disciples, Wednesday, March 15, 1848 (Boston: Benjamin H. Greene, 1848)

- ↑ William Henry Lyon, The First Parish in Brookline: An Historical Sketch (Brookline: First Parish in Brookline, 1898)

- ↑ "For Sale," Boston Daily AdvertiserJuly 22, 1856, 1.

- ↑ "BKL.1706." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ Julius A. Stratton and Loretta H. Mannix, Mind and Hand: The Birth of MIT (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005)

- ↑ "MLT.178." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "NAH.61." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ John Murray Forbes, Reminiscences of John Murray Forbes, vol. 3, ed. Sarah Forbes Hughes (Boston: George H. Ellis, 1902)

- ↑ Douglass Shand-Tucci, Built in Boston: City and Suburb, 1800-2000 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999)

- 1 2 Keith N. Morgan, Buildings of Massachusetts: Metropolitan Boston (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009)

- ↑ Bryant F. Tolles Jr., Architecture & Academe: College Buildings in New England Before 1860 (University Press of New England, 2011)

- 1 2 Bainbridge Bunting, Harvard: An Architectural History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985)

- ↑ "QUI.1276." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ James L. Yarnall, Newport Through its Architecture (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2005)

- ↑ Architectural Sketch-book 3, no. 9 (September 1873): n. p.

- ↑ The Architecture of Baltimore: An Illustrated History, ed. Mary Ellen Hayward and Frank R. Shivers Jr. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004)

- ↑ Library Journal (March 1878): 29.

- ↑ "312 Marlborough." backbayhouses.org. Back Bay Houses, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- 1 2 "Cabot & Chandler, Architects," -nebraskahistory.org, Nebraska State Historical Society, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "The Illustrations," American Architect and Building News 7, no. 223 (April 3, 1880): 141.

- ↑ "Amos J. Boyden, F. A. I. A." Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual Convention of the American Institute of Architects (Washington: Gibson Brothers, 1904)

- ↑ "BKL.1084." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "The Illustrations," American Architect and Building News (May 20, 1882): 233.

- ↑ "195 Marlborough." backbayhouses.org. Back Bay Houses, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "276 Marlborough." backbayhouses.org. Back Bay Houses, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- ↑ Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., Bar Harbor (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2011)

- ↑ Louis Cabot House NRHP Registration Form (1983)

- ↑ "CAM.4." mhc-macris.net. Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d. Accessed June 25, 2021.