Edward E. McClish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1909 Wilburton, Oklahoma |

| Died | 26 October 1993 (aged 84) Raymore, Missouri[1] |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1932–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

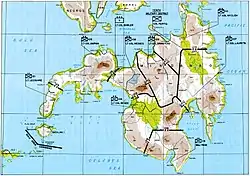

Edward Ernest McClish (1909-1993) was an American military officer in the Philippines in World War II. During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Lt. Colonel McClish commanded a division of Filipino guerrillas on Mindanao island.

Early life

Ernest E. McClish was the son of Ross Enzire McClish, a Choctaw Nation citizen listed as "full blood" on the Dawes Rolls,[2] and Minnie Lee Mosteller. McClish graduated from Haskell Institute in 1929 and Bacone College in 1931 and became an army officer. He entered on active duty with the National Guard in 1940 and in 1941 commanded a company of Philippine Scouts. He became a battalion commander in August 1941 and was on the island of Negros when World War II began in the Philippines on 8 December 1941.[3][4]

Contemporaries described McClish as a handsome, soft-spoken Oklahoman and a "colorful guerrilla leader" with a quiet manner who dealt with problems in a methodical manner rather than barking out orders. He suffered from malaria and got out of a hospital bed to avoid surrender to the Japanese.[5] Guerrilla leader Robert Lapham said the McClish was "sometimes criticized for his alleged lack of seriousness", but "got on remarkably well with Filipino civilians and established advantageous relations with them by being affable and approachable." Major (later General) Stephen Mellnik and Commander Melvyn McCoy, escaped prisoners of war, were helped by McClish and were favorably impressed by him.[6]

World War II

General Jonathan Wainwright surrendered all U.S. forces in the Philippines in May 1942. On the island of Mindanao at this time, McClish responded to Filipino authorities who asked him not to surrender but to combat the banditry that was running rampant after the defeat of the American and Filipino forces. McClish and about 190 American soldiers and civilians who refused to surrender began to organize guerrilla forces on Mindianao.[7][8] Mindinao was not as heavily occupied as Luzon, the other large island of the Philippines. The Japanese occupiers were estimated to number 50,000 soldiers[9] and controlled only the larger cities and main roads and waterways. The guerrillas had more freedom of movement and easier coordination with each other than on Luzon.[10] The guerrillas "ran schools, courts, tax collecting, trade, and began printing money."[11]

By September 1942, McClish had established one of the first guerrilla units on Mindanao with more than 300 Filipino volunteers under his command, half of them armed.[12] On 20 November 1942, McClish, a major, and Captain Clyde Childress met with Wendell Fertig, a self-proclaimed general officer. They accepted Fertig's authority to command guerrilla forces on Mindanao. Fertig promoted McClish to lieutenant colonel and appointed him the commander of the 110th Division with responsibilities in four northeastern provinces of Mindanao and with Childress as his second in command.[13] The 110th division of McClish eventually had a complement of 317 officers and 5,086 enlisted men, nearly all of them Filipinos, including some Moros. The primary task given to McClish and other guerrillas on Luzon by the U.S. Army commanders in Australia was intelligence gathering. The guerrillas were ordered to avoid combat when possible with the Japanese, a directive they sometimes ignored.[14]

McClish's most ambitious military endeavor was probably the siege of the town of Butuan from 3 to 10 March 1943. Two thousand of McClish's guerrillas besieged the Japanese contingent in a schoolhouse. The siege was broken when Japanese reinforcements arrived 10 March. Twenty guerrillas and an estimated 50 Japanese were killed. Although the siege was a failure, it apparently won credibility for the guerrillas among the local people as fighters, not just refugees hiding in the mountains. The siege also resulted in a de facto agreement between the local Japanese commander and the guerrillas which gave the guerrillas freedom of movement in most of the region in exchange for the Japanese rarely venturing outside the towns and cities they occupied. That became important for intelligence operations and the reception by the guerrillas of supplies delivered by submarines. However, Fertig criticized McClish for the expenditure of scarce ammunition in the siege.[15] [16]

Also in 1943, when coastwatcher Chick Parsons arrived on Mindanao to carry out MacArthur's mandate to focus on intelligence gathering, McClish provided him with personnel for his coast watching station, fueled his launch with diesel distilled from coconuts, and mounted a .50 caliber machine gun on his boat.[17]

Problems with Fertig

McClish and his chief of staff Clyde Childress had a rocky relationship with Wendell Fertig, the self-proclaimed brigadier general in charge of Mindinao guerrillas. (Fertig's assumption of the rank of general also irritated General MacArthur's headquarters in Australia.) Part of the problem may have been that Fertig's headquarters in the Agusan River valley were close to McClish's area of operation and thus Fertig was in closer proximity to McClish than with his other divisional commanders. Fertig's opinion was that McClish and Childress were "disloyal, incompetent," and had done little for the guerrilla movement on Mindanao. Specifically, he said McClish was a last-second planner, too aggressive in wanting to battle the Japanese, and had chosen his subordinates unwisely. McClish and Childress were among several American officers serving under Fertig who requested transfers from the guerrillas to regular U.S. army commands which became possible after the U.S. invasion of the Philippines on 20 October 1944. At their request, Fertig relieved Childress on 29 December 1944 and McClish on 23 January 1945.[18]

Robert Lapham described McClish and Childress's opinion of Fertig as "paranoid and consumed with personal ambition, not to speak of ungrateful and discourteous to them after they had made it possible for him to move his headquarters to a safe location."[19]

Notes

- ↑ "Ernest Edward McClish". Family Search. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ "Ross McClish". Search the Dawes Rolls: 1898-1914. Oklahoma Historical Society.

- ↑ "A Choctaw Leads the Guerrillas". Indians in the War 1945. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ↑ Lapham & Norling 1996, p. 253.

- ↑ Holmes 2009, p. 74.

- ↑ Mellnik 1969, p. 291.

- ↑ Morningstar 2018, p. 878.

- ↑ Holmes, 2015, Location 99. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Anderson, Charles R. Leyte 17 October 1944 - 1 July 1945. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. p. 10. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ "United States Army Reconciliation Program of Philippine Guerrillas". Headquarters Philippine Command, United States Army. National Archives. pp. 40–41. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ Morningstar 2018, p. 278.

- ↑ Choctaw

- ↑ Childress 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Holmes, 2015, Location 1864-1873. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Holmes, 2015, Kindle location 1933-1947, 2547-2553

- ↑ Morningstar 2018, pp. 473, 794.

- ↑ Morningstar 2018, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ Holmes, 2015, Location 913, 2518-2643, 2992, 3361, 3531. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Lapham & Norling 1996, p. 110.

References

- A Choctaw Leads the Guerrillas, Naval History and Heritage Command, retrieved 15 January 2022

- Childress, Clyde (2003). "Wendell Fertig's Fictional "Autobiography": A Critical Review of They Fought Alone" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Historical Collection. 31 (1). Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Holmes, Kent (2015). Wendell Fertig and his Guerrilla Forces in the Philippines. West Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 9780786498253.

- Holmes, Virginia Hansen (2009). Guerrilla Daughter. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873389495. Retrieved 23 January 2022. Downloaded from Project MUSE.

- Lapham, Robert; Norling, Bernard (1996). Lapham's Raiders. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813119499.

- Mellnik, Stephen Michael (1969). Philippine War Diary 1939-1945. New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold.

- Morningstar, James Kelly (2018). War and Resistance: the Philippines, 1942-1944 (PhD). University of Maryland. hdl:1903/20956. Later published as War and Resistance in the Philippines, 1942-1944. Naval Institute Press. 2021. ISBN 978-1-68247-629-1.