Edward Francis Wells | |

|---|---|

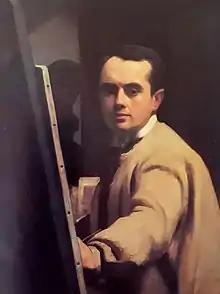

Photograph of the artist, c.1898 | |

| Born | Edward Francis Wells 1876 Chinsurah, India |

| Died | 1952 London, England |

| Education | St John's Wood Art School; Royal Academy Schools |

Edward Francis Wells was a painter of pastoral scenes and portraits. He trained at the Royal Academy Schools and painted in a traditional ‘old master’ style. He exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition and at smaller commercial galleries in London and elsewhere. The artist signed his work E. F. Wells.

A Dorset upbringing

Edward Francis Wells was born in Chinsurah, India, on 3 April 1876.[1] His father, William Howley Wells (known as Howley), worked in the Indian Civil Service as an engineer, and his mother was Annie Maria Wells (née Ring). Edward had a younger sister, Maud, but two older siblings had died of cholera, and it was health concerns that led the family to move back to England in 1879.[2] Shortly after the family’s return to England and through fellow old Etonian Henry Fox-Strangways (who was now the 5th Earl of Ilchester), Howley Wells was offered the stewardship of Fox-Strangways’s estate at Melbury Park, Dorset. The family moved into a tied property at Evershot on the edge of the estate,[3] where his parents were to live for the next thirty years.

An art education

At the age of nine Edward was sent to a preparatory school at Bournemouth and two years later progressed to Clifton College, a private boarding school in Bristol, where he met Frank Moss Bennett (1874–1952), who was to become a lifelong friend and a popular artist.[4] In the early 1890s Wells expressed his ambition to be an artist, and his family encouraged him by adapting a milking parlour into a studio.[5]

Wells and Bennett both first attended the Slade School of Art[6] and then briefly attended St John's Wood Art School before almost four years at the Royal Academy Schools (from February 1896).[7] In his first year at the Royal Academy Schools, Wells won the Creswick Award for best landscape painting with A Farm on the Hill[8] – a picture that was selected for the Royal Academy's summer exhibition the following year.[9]

In March 1900 Wells and Bennett travelled to Italy, visiting Florence, Siena, Rome, Naples, Capri and Venice. They returned to England in 1901, and formally left the Royal Academy Schools in January of that year.[7]

Patronage and a one-man show

Keen to establish himself as a professional artist, Wells rented a studio in Chelsea – considered London’s art centre[10] – and in February 1902 he joined the Chelsea Arts Club. Under the patronage of two of the younger members of the Fox-Strangways family,[11] a large exhibition of Wells’s watercolour sketches took place in Dorchester; works included were Italian pastoral scenes, Dorset scenes and also some pastel portraiture.[12] Wells’s father had strong views on art and favoured the ‘old masters’. He was somewhat obsessed by technique and by a pseudo-scientific pursuit of objective reality through the ‘true’ rendering of colour and tone. In this respect he seems to have been influential on Edward’s evolving style of picture-making. Howley was also Edward’s financial backer. The father and son’s preference for the training he received at the Royal Academy Schools over the Slade School of Art also indicates their conservative view of art. Wells’s work always demonstrated a desire for technical exactitude, and he undoubtedly had a particular facility to create a good ‘likeness’ in portraiture.[13]

The Wells family’s social connections to the landed gentry and its ‘old-boy network’ placed Edward in a good position to set up himself up primarily as a portrait painter. Initially he often worked in pastels – which let him work quickly, often requiring only one sitting. Selections of these pastel portraits were exhibited at the Carlton Gallery London in 1904.[14]

Courting

Throughout this period Edward had been courting Anne Helen Pellew, the daughter of an Indian Civil Service judge.[15] Like Edward, although born in India, she had grown up in England. Her family had a Clifton address,[16] and it seems likely that the two became acquainted when Wells was at school there. She was musical, poetic, ‘very delicate’, and came to ‘adore’ Edward, who apparently ‘ministered to her every need’.[17]

Anne frequently stayed at Wimbledon, in south London, where her mother owned a property. When she could escape her six siblings, Anne and Edward enjoyed London life, attending concerts, exhibitions and the theatre, and liking to eat at fashionable ‘bohemian’ restaurants on the Fulham Road, near Edward’s studio. This was the era of Edwardian country-house parties, and weekends were often spent at the homes of family friends and sometimes gatherings at Evershot. A portrait of ‘Annie’ was selected for the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1905.[18]

It was presumably through Frank Bennett’s close friendship with Wells that Frank met Anne’s sister Margaret, and the two were married in August 1907.[19]

Exhibition success

Aside from the commercial necessity to paint portraits, Wells’s artistic preference was for pastoral subjects. He exhibited pastoral watercolours at Dudley Art Society[20] and at the Modern Gallery in Bond Street.[21] More ambitious oil paintings – such as Milking Time, exhibited at the Grafton Galleries, London, in 1905 – reveal painstaking attention to detail.[22] Vera Campbell, writing in The World, felt that ‘praise can be given to Mr. E. F Wells’s Milking Time, with its pleasant reminiscence of Richard Wilson’s landscapes.’[23]

By 1907 Wells was having further exhibiting success: rural scenes were exhibited with the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour and at the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and a group portrait of Captain Peter Ormrod’s children Maggie, Guy and Joan[24] was selected for the RA summer exhibition. Despite this success, when Anne and Edward explained their plans to marry, Wells’s father was brutally frank about the reality of Edward becoming self-supporting as an artist:

Your prospects in the profession are still as you will allow, very precarious indeed & must be the cause of anxiety, and however good your work may be it has yet to be recognised. To risk the responsibilities of marriage & with heavy studio rent to be paid out on such small means certainly amounts to a gamble which in my opinion no one has a right to undertake.[25]

A creative peak

The couple were determined to go ahead with the marriage; however, in July 1909, before the wedding, Edward’s father unexpectedly died of a stroke. While this was seen as a personal tragedy by Edward – who greatly admired his father – it did result in an inheritance from a trust that his father had set up for Edward, his sister and their mother. Around the same time a further modest legacy from a cousin provided the couple with some additional security.[26] They married in early 1910[27] and honeymooned in Corsica – which inspired Wells’s Distant View of Ajaccio.[28] Edward was now brother-in-law to his best friend, Frank Bennett (who became a popular and successful artist of historical subjects).

Edward and Anne initially lived at Wells’s rented studio in Chelsea;[29] but when their daughter Judith was born,[30] they moved to bigger rented premises, also in Chelsea.[31]

The next few years saw Wells at the height of his artistic ambitions, working on a larger scale; The Shower of Gold,[32] a reinterpretation of the legend of Danae, was selected for the Royal Academy in 1911 and was well received: ‘Laburnums droop over a nude girl lying asleep below the vivid bloom: the effect is superb, and very decorative.’[33] Anne (known to Edward as ‘Nan’) initially posed for the female figure, before a professional model took up the pose. The painting apparently achieved the accolade of a parody in Punch.[34] The following year a pastoral scene of harvest time, The Last Load, was also selected for the Royal Academy.

In October 1913, Edward and Anne moved out of London and rented a cheaper and larger property in Milton Abbas, Dorset; and by the following year there were three children – Judith (b.1911), Sylvia (b.1912) and Bill (b.1914)[35] The return to Dorset inspired the large and dramatic Wareham Heath, Dorset. Soon, however, the First World War was affecting all aspects of life in Britain, and opportunities for portrait commissions were few; Wells now worked mainly on small watercolour pastoral scenes. When their three-year lease expired and there was no end to the war in sight, they moved to Wimbledon, where Wells’s mother-in-law still owned a property.[36]

In 1916 conscription was introduced for men aged from 18 to 41, and in May 1917 Wells – then 41 – was called up for military service.[37] He was placed in category C1 – ‘Garrison Service at Home Camp’[38] – and after initial training in Norfolk he was posted to the War Office in London, where he carried out clerical duties until he was demobilised in February 1919.[39]

Family tragedy and diminishing income

Following the war, Wells worked to rebuild his portraiture business. A big boost was a commission to paint Lady Romayne Cecil, the daughter of the Marquis of Exeter, whose family home was Burghley House in Stamford.[40] Anne’s health was now of great concern, however: she had been suffering from ‘lung problems’ for some time, and tuberculous had now set in. Portraits of Anne and their son William from this time are distinctly sentimental – for example, Madonna and Child and The Boy and the Apple. As ‘Nan’s’ health deteriorated, her cousin Edward Pellew (the 8th Viscount Exmouth) stepped in financially, paying for visits to the Pyrenees, where he had property, and to Switzerland, where it was hoped that the altitude would help her.[41] The alpine surroundings inspired Wells’s painting but unfortunately failed to revive Anne’s health, and she died in their Upper Norwood home in 1924.[42]

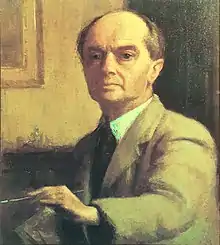

Understandably, Wells was in ‘an emotionally unsettled state’,[43] and his mother (‘Granny Wells’), who had some independent financial means, moved into the Norwood home to provide support for the now teenage children. A strong-minded and right-wing matriarch, she set about organising the household, the children and to some extent Edward’s professional life.[44] His income essentially came from portrait commissions, and his social connections continued to pay off in this respect; but increasingly the portraits were done through necessity rather than choice, some commissions coming via an agent.[45] For a standard head-and-shoulders oil portrait (30 × 25 inches; 76×63 cm), Wells would charge about 50 guineas[46] (equivalent to about £2,300 in 2021[47]). Some of his paintings were based on photographs – Edward often received acclaim for reproducing a likeness without having met the person depicted.[48] The need to provide for his family financially was increasingly becoming burdensome to him. Anthony Hull, Wells’s biographer, comments: ‘Edward appeared to have slowed down somewhat by the end of the decade. Exhausting emotional problems, his reluctance to adapt his style to changing fashion, and his own advancing years contributed to this.’[48] His mother bluntly explained their finances to him in 1931: ‘Our income is diminishing year by year! Let us hope it may take an upward turn before long, or we shall have very little left.’[49]

Travelling around Britain

With Granny Wells now in her eighties, it was Wells’s sister-in-law Caroline Pellew who kept the family together. When Granny Wells died, in 1932, Wells relieved himself of financial worry by selling the Upper Norwood home. His daughters, Judith and Sylvia, were in their twenties and were making lives for themselves;[50] and although his son, William, was still at the St Andrew's University, he was mainly supported by Caroline Pellew.

Wells had sufficient income to keep a small London studio in Westminster[51] that enabled him to store his paintings while he withdrew from London life – making extensive watercolour painting trips around England and especially Scotland, staying in guest houses and hotels.

A new life begins

In 1935 his friend and agent Willy Turner encouraged Wells to return to London, where he took lodgings in Hampstead. Turner later introduced him to Katharine (‘Kay’) Dunn,[52] who would become his second wife. She was twenty-five years younger than him, and he seems to have been drawn to her vivacious and self-confident approach to life. She had trained in ballet at Madame Vandyck’s Academy in Swiss Cottage, London, and had been selected to be a prima ballerina with the Carl Rosa Opera Company, with whom she appeared on Broadway in New York. When she met Edward she was a divorcee with a young son and had presumably abandoned her ballet career.[53]

Her ‘passionate sincerity and admiration of his art’[54] awoke a new sense of purpose in Edward. The couple married within a year of meeting,[55]initially renting a flat by Hampstead Heath and later leasing a Victorian house at 39 Parkhill Road, Hampstead. With premises large enough to display Edward’s stock of unsold paintings, his creativity was reawakened, and Kay dedicated herself to promoting her husband’s work.

They led a hectic cultural life, attending Myra Hess’s concerts, John Gielgud and Peggy Ashcroft’s theatrical performances, and Royal Academy soirées. In the summer they enjoyed the tennis at Wimbledon. They held extravagant parties and lived beyond their means. Wells sold his share in a valuable Hampstead property to his father’s solicitor, which partly offset their expenses, and he undertook further portrait commissions. The exhibitions that Kay organised at the Walker’s Galleries in New Bond Street (essentially retrospectives) were well received, but led to few sales.[56]

Later years

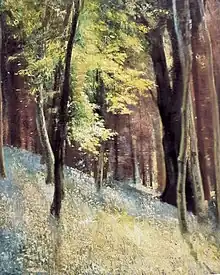

Early in the Second World War, Kay and Edward were ‘virtually bombed out of their home’ when an unexploded bomb landed outside their front door creating a ‘terrifying hole’.[57] Kay’s son rescued Wells’s paintings from the house, and the family moved into a hotel in Belsize Park until they could move back a year later. Edward had suffered a stroke in June 1940 and lost the use of a leg;[57] however, he was able to continue working, and a watercolour – Spring Woodland – was accepted for the Royal Academy in 1941.[58]

When Wells’s sister died in 1942 his and Kay’s assets were strained further through the requirement to pay death duties on Maud’s share of the joint trust. In 1944 they sold the remainder of their lease on 39 Parkhill Road and rented premises in Knightsbidge, London on the corner of Cadogan Place and Sloane Street. Here, from February 1945, they opened the ground floor as an art gallery dedicated to Wells’s work.[59] Largely due to its prosperous location, the venture was an apparent success: Wells’s stock of canvases and watercolours sold well, and there was a boom in commissions for portraits – especially based on photographs of relatives lost in the war. But this demand for portraits was also a huge drain on the artist as he entered his seventies. The gallery closed in 1949, and Kay and Edward retired to a flat firstly at 88 Cadogan Place and then at 20 Hans Place, Knightsbridge. On 19 August 1952 Edward collapsed near Sloane Square underground station and he died on the way to hospital.[60]

References

- ↑ ‘British India Office Births and Baptisms’, findmypast.co.uk.

- ↑ Anthony H. Hull (1990), E. F. Wells: His Art, Life and Times (Stroud: Sutton), p. 1.

- ↑ Address: ‘Moorfields’, Evershot, Dorset. Reference: Hull, 1990, p. 1.

- ↑ Rehs Galleries https://rehs.com/eng/default-19th20th-century-artist-bio-page/?fl_builder&artist_no=335&sold=1.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 5.

- ↑ Student records show Wells starting at the Slade in 1892.

- 1 2 "Edward Francis Wells | Artist | Royal Academy of Arts". Royal Academy.

- ↑ The Creswick Prize was £30. Reference The Art Journal, 1897 at https://archive.org/details/sim_art-journal-us_1897/page/n453/mode/2up?q=%22Edward+Francis+Wells%22

- ↑ "1897 Fancy Dressing".

- ↑ No. 11 Onslow Studios, Onslow Place, Chelsea.

- ↑ Lady Helen Vane-Tempest-Stewart (the Countess of Ilchester) and her sister-in-law Lady Muriel Augusta Fox-Strangways. Ref: Hull, 1990, p.8

- ↑ The exhibition took place at Henry Duke Company, South Street, Dorchester, in 1902. 230 works were exhibited. Hull, 1990, p. 8.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p.109

- ↑ Carlton Gallery at Pall Mall Place, London. For an example of Wells’s pastel portraits of this period see The Hon. Margaret Bruce (1882–1947), Countess of Bradford 1905. Reproduced at https://artuk.org/discover/artists/wells-edward-francis-18761952-58449.

- ↑ Born 30 April 1879 in Fort William, Bengal, India, http://www.townsley.info/Strangeway/GedSite/g4/p3969.htm#i198404.

- ↑ Address: Rodney House, Clifton.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 28.

- ↑ "1905 John Singer Sargent "In Full Sail"".

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 32.

- ↑ Firstly in the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, before 1904 and later at the Alpine Club in Conduit Street.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 10.

- ↑ ‘Autumn Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries’ 1905.

- ↑ The World, 7 November 1905.

- ↑ Captain Peter Ormrod (1869–1923) had inherited Wyresdale Hall and a 6,000-acre (2400-hectare) estate within the Forest of Bowland, Lancashire, in 1895.

- ↑ Letter, W. H. Wells to E. F. Wells, 16 July 1909. Quoted in Hull, 1990, p. 37.

- ↑ England and Wales Government Probate Death Index , 1858–2019 at findmypast.co.uk records W. H. Wells’s death on 21 July 1909. The effects totalled £24,588 to be divided between William’s wife and their two children.

- ↑ 4 January 1910. Hull, 1990, p.38.

- ↑ Purchased by Huddersfield Corporation following an exhibition at the town’s art gallery. Hull, 1990, p. 40.

- ↑ Wells was renting Rossetti Studios in Rossetti Gardens near Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, from 1908. Ref.: Royal Academy Exhibitors 1905–1970 volume VI, SHERR–ZUL, EP Publishing, 1982.

- ↑ Judith Wells born March 1911, Hull, 1990, p. 40.

- ↑ Cedar House, at 48 Glebe Place, for which they paid £150 a year. Hull, 1990, p. 42.

- ↑ https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/edward-francis-wells-the-shower-of-gold-221-c-cd74bf6838 gives the size as ‘55 x 39 1/2 inches' (140×100 cm).

- ↑ Academy 13 May 1911.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p.128 cites Punch, c. May 1911, although this reference has not been confirmed.

- ↑ Delcombe Manor is at Milton Abbas, Dorset, Hull, 1990, p. 42. References for Judith and Sylvia’s birth dates on p.40 and Bill’s on p.50

- ↑ 7 North View, Wimbledon. Hull, 1990, p. 46.

- ↑ Private in the 7th Platoon, B Company, of the 17th Essex Battalion.

- ↑ See https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/blog/2017/01/16/conscription-the-first-bill-of-conscription-introduced-to-british-parliament

- ↑ Hull, 1990, pp. 47–9.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p.53.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 58.

- ↑ They had purchased and moved into ‘St. Margaret’s’, 63 Beulah Hill, Upper Norwood, Crystal Palace, in south London, in 1922. Hull, 1990, p. 50.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p.60.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, pp. 60 and 66.

- ↑ Willy Turner, friend, ex-proprietor of the Carlton Gallery, Pall Mall and later Wells’s agent Hull, 1990, p.62 and p.10

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p.63

- ↑ Based on 50 gns in 1924. "Inflation calculator", Bank of England.

- 1 2 Hull, 1990, p. 63.

- ↑ Letter, Mrs W. H. Wells to E. F. Wells, 7 July 1931 quoted Hull, 1990, p. 63.

- ↑ Judith and her husband emigrated to South Africa, and Sylvia – a communist – moved to Russia in 1937. Hull, 1990, p. 67.

- ↑ The studio in Tatchbrook Street, Westminster, cost only £8 a quarter. Hull, 1990, p. 68.

- ↑ Born Kathleen Ormsby Stather Dunn in February 1901

- ↑ Hull, 1990, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 69.

- ↑ Hampstead Registry Office, 18 September 1935. Hull, 1990, p. 71.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, pp. 77–9.

- 1 2 Hull, 1990, p. 82.

- ↑ "1941 Mutable Meaning in Duncan Grant's Girl at the Piano". chronicle250.com.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, p. 88.

- ↑ Hull, 1990, pp. 81–91 and p.101 and ‘England and Wales Government Probate Death Index , 1858-2019’ at findmypast.co.uk. His effects totalled £858 (equivalent to about £17,500 in 2021)

External links

- Artworks by or after Edward Francis Wells at the Art UK site