Edward John Newell | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1771 |

| Died | 1798 (aged 26–27) |

| Nationality | Irish |

Edward John Newell (1771–1798), was an Irish sailor, glazier, artist, and portrait painter, notorious for his role as a government informer during the political turmoil of the 1790s. Shortly after joining the republican Society of United Irishmen in 1796 he offered his services to the Crown authorities. Following the publication of a confessional autobiography, in 1798 he disappeared amidst rumours of assassination.

Early life

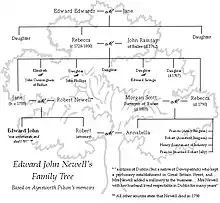

Newell was born in Downpatrick on 29 June 1771 to parents Robert and Jane Newell.[1][2] He was of Scottish ancestry. As a child, he was prone to misbehavior.[3] In his youth, Newell put up a false facade in front of his friends to hide who he really was to them.[4][5]

Aynsworth Pilson wrote in his memoirs,[6] that Newell's parents lived in Dublin before they moved back to Downpatrick. Pilson also wrote that Robert Newell ran a perfumery in Dublin, and that Jane Newell operated a millinery business.

When Newell was seventeen,[3] his father was seriously injured in a horse accident while he was away on business. Newell's mother left Edward in charge of the house while she attended to Robert. Newell later abandoned his younger brother and the house to visit his sick father at his uncle's home. His mother, who never showed much affection for Newell, was not pleased to see her son turn up.[3]

Employment

After the falling out with his mother, he sought work. Newell met Captain Johnson, who enlisted Newell as a seaman. Newell soon left port for Cadiz, Spain.[2] For about one year, Newell was at sea; he later described some of the hardships of that experience, including "a most dreadful storm" and living for six weeks "on raw meat, lying in wet clothes, and constantly working at our pumps."[7]

After returning home to Dublin and telling his father of his voyage, his father asked Newell to settle down and found him employment in a painting and glazing business, which Newell wrote that he begrudgingly followed for about a year until his "usual licentiousness occasioned a difference" with his employer.[8]

Newell soon became a glass-stainer for the next two years, before a falling out with his employer and his father.

Following a failed attempt to emigrate to America, he moved on to Limerick and Dublin,[9] trying to find a job but never holding one down for long. He found himself in almost complete poverty, and when he asked his parents for assistance, he was denied due to his enthusiastic support of the United Irishmen.

In 1796, Newell moved to Belfast, where he started his own portrait and miniature painting business.[10] Newell had never attempted miniature painting before, and he had received no instruction in the vocation.[11]

Two of Newell's known paintings are a self-portrait that he included in his later biography, and a portrait of Betsy Gray, who fought and died at the Battle of Ballynahinch.[12]

Informer among the United Irishmen

Newell officially joined the Society of United Irishmen in 1796.[13]

Newell neglected his business due to his over-enthusiasm for the United Irishmen, and he quickly began to raise the movement leaders' suspicions. His younger brother, Robert (not a United Irishman), described Newell as being "in the practice of going through the town of Belfast disguised in the dress of a light horseman, with his face blackened and accompanied by a guard of soldiers, pointing out certain individuals who have in consequence been immediately apprehended and put in prison".[14]

Through his business, he became acquainted with George Murdoch, and Newell painted the interiors and exteriors of Murdoch's house. Murdoch and Newell were opposites politically; their association increased distrust of Newell within the United Irishmen. Newell hired guards to protect Murdoch's house because of their friendship. Newell later wrote that Murdoch informed him that he know that Newell was a rebel. However, Newell's 1843 biographer, Madden, wrote that "he betrayed the secrets of the United Irish Society professedly to prevent the murder of an exciseman named Murdock".[15]

Under-Secretary of State for Ireland Edward Cooke brought Newell to Dublin Castle to be questioned.[8] Newell wrote that he was given a good reception and treated well and that he was even offered wine. Newell asked to be pardoned in exchange for his knowledge, which the Lord Lieutenant granted him in writing. Cooke initially questioned Newell for nine hours.

Newell was examined by a secret committee of the Irish House of Commons[16] in early 1797, where he was put on a high chair in order to be heard better by his audience. Newell later admitted that he deliberately exaggerated and fabricated his testimony in order to scare the committee.[2]

In 1798 Newell pretended that he showed remorse for his treachery and for making many enemies. Soon after, he told Cooke that he no longer wanted to be a spy.[2] It was decided that he should move to Worcester[2] under the false name of Johnson, where he would resume his painting career.

Portrait of Betsy Gray

Among "Other Stories and pictures of '98", the Mourne Observer reproduces "a miniature of Betsy Gray" which was attributed (possibly apocryphally)[18] to "Newell of Downpatrick".[17]

This miniature of Betsy Gray, which is in the possession of Mr. C. J. Robb, Spa, was first published in the 1920's in a booklet "Out in '98". It was reproduced from a painting by a man called Newell of Downpatrick, who posed as a United Irishman prior to 1798, but who was, in fact, in the pay of the Government.

According to a number of published accounts (some contemporary) and to popular ballads, Elizabeth, "Betsy" or "Bessie" Gray, was the daughter of a County Down Presbyterian farmer, and a "wondrous beauty" (the "Pride of Down"), killed by government Yeomanry following the rout of the United Irish host a Ballynahinch. She is depicted as riding into the fray carrying the green rebel flag, and being subsequently executed by "Yeos" (her "glove hand" severed, and shot through the head) alongside her brother George and "her sweetheart, Willie Boal".[19][20][21] No connection appears to be drawn between her fate and Newell's treachery. In the years that followed "a rough map representing the battle scene" with Gray "mounted on a pony and bearing a green flag" was reportedly "seen hanging in many a cottage".[19]

Autobiography

Shortly after Cooke interviewed Newell for the last time, Newell published The Life and Confessions of Newell, the Informer, his autobiography,[2] which was claimed to be printed in London but was really printed in Belfast in private by printer John Storey.[2] Newell wrote his autobiography during his hiding-out period in Doagh, a few miles from Belfast. Newell claimed that £2,000 was given to him as a reward for causing 227 innocent men to be confined to cells, bastilles, or tender holds, and that many of the men died in confinement. He also acknowledged that one of his victims, the Rev. Sinclair Kelburn, was barely known to Newell save for a brief conversation they had on the street. Newell's book was dedicated to John Fitzgibbon, 1st Earl of Clare, and contained a self-portrait. Newell's book had a large sale and it gained much attention.[22]

Attempted escape and disappearance

Newell began an affair with the wife of his friend George Murdoch while he was in Belfast Lough.[23] Newell persuaded her to leave her husband and to move near his own house. Twelve days later, Newell found that a ship that would take him to America was nearby on the Lough, so he wrote to George Murdoch telling him his wife's whereabouts and of her decision to return to him.

Newell most likely did not move to America, as there are several differing accounts of his death in 1798 at the age of 27. These accounts of Newell's death all share one thing in common: that the United Irishmen assassinated him.[23]

Madden records that around 1828, partly uncovered human bones that are said to be of Edward John Newell were found on the beach of Ballyholme, Bangor, County Down, indicating that he drowned there.[24]

References

- ↑ Dawson, Kenneth L. "Newell, Edward John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20004. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leslie, Stephen (1894). Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. Vol. 40 Myllar–Nicholls. London: Elder Smith & Co.

- 1 2 3 Newell, Edward John (1798). The Life and Confessions of Newell the Informer.

- ↑ Madden, Richard Robert (1843). The United Irishmen; Their Lives and Times. London.

- ↑ Harwood, Philip (1844). History of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Ireland: Chapman & Elcoate. p. 129.

to every friend or party he connected himself with he was false.

- ↑ Pilson, Aynsworth (2016). Notable Inhabitants of Downpatrick. Downpatrick: Lecale & Downe Historical Society. ISBN 9790957671828.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ↑ Madden, Richard Robert (1843). The United Irishmen; Their Lives and Times. London. p. 118.

- 1 2 Borohme, Brian (1843). Ireland, as a Kingdom and a Colony; or a Historical, political, and military. Nabu Press. p. 394. ISBN 9781287904175.

- ↑ Strickland, Walter. "Edward John Newell, Miniature Painter – Irish Artists". Library of Ireland. Dictionary of Irish Artists (1913). Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ Sirr, Henry Charles; Reynolds, Thomas; Newell, Edward John; O'Brien, J (1846). The Mercenary Informers of '98: Containing the History of E. Newell, Major Sirr, J. O'Brien, and T. Reynolds. With the Secret List of the Blood Money Paid by the English Government from 1797 to 1801. MS. Notes.

- ↑ Madden, Richard Robert (1843). The United Irishmen; Their Lives and Times. London. p. 541.

- ↑ Lyttle, W. G.; Rowlinson, Derek A. (26 April 2015). Betsy Gray or Hearts of Down A Tale of Ninety-Eight (Reprint ed.). Books Ulster. p. 159. ISBN 978-1910375211.

- ↑ Newmann, Kate. "Edward John Newell". Dictionary of Ulster Biography. Dictionary of Ulster Biography. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ "The United Irishmen: Informers, Informants & Information". History Ireland. 6 (2). Summer 1998.

- ↑ Harwood, Philip (1844). History of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Ireland: Chapman & Elcoate. p. 272.

- ↑ Gilbert, Sir John Thomas (2017) [1893]. Documents Relating to Ireland, 1795–1804: Official Account of Secret Service. Forgotten Books. p. 104. ISBN 978-1527825581.

- 1 2 "Betsey Gray or Hearts of Down Other Stories and Pictures of '98. as collected by and published in The "Mourne Observer"". Lisburn.com. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ "Betsy Gray miniature, Mourne Observer, 5 July 1968, p. 9; originally published in an obscure publication in the 1920s and attributed apocryphally to the notorious informer Edward Newell". HistoryHub. University College Dublin School of History & Archives. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- 1 2 M'Comb's Guide to Belfast. The Giant's Causeway and Adjoining Districts of The Counties of Antrim and Down with A Map of Belfast [Fist Published 1861] (PDF). Belfast: SR Publishers Limited. 1970. pp. 129–132. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ M'Skimin, Samuel (1849). Annals of Ulster, or, Ireland fifty years ago. Belfast: J. Henderson.

- ↑ Lyttle, W. G. (1968). Betsy Gray or, Hearts of Down: a Tale of Ninety-Eight (PDF). Newcastle, Northern Ireland: Mourne Observer Limited. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ Newman, Kate. "Edward John Newell (1771–1798): Artist & Informer". Directory of Ulster Biography.

- 1 2 Infield, H. J. (1883). The Oracle. Vol. 8. H. J. Infield. p. 369.

- ↑ Maxwell, William Hamilton (1854). History of the Irish rebellion in 1798: with memoirs of the union, and Emmett's insurrection in 1803. London: H.G. Bohn. p. 272.