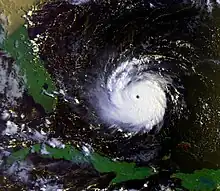

Hurricane Andrew approaching the Bahamas | |

| Category 5 hurricane | |

|---|---|

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 923 mbar (hPa); 27.26 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 direct, 1 indirect |

| Damage | $250 million (1992 USD) |

| Areas affected | Northwestern Bahamas |

Part of the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| General

Effects Other wikis | |

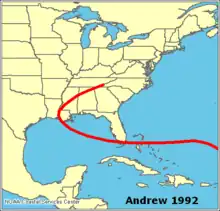

The effects of Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas included three direct fatalities and $250 million (1992 USD) in damage. Forming from a tropical wave on August 16, Andrew remained weak until rapidly intensifying on August 22, and late on August 23 it made its first landfall in The Bahamas on Eleuthera as a Category 5 hurricane with winds of 260 km/h (160 mph); early the next day Hurricane Andrew passed through the southern Berry Islands with winds of 240 km/h (150 mph). The hurricane later made a devastating landfall in southern Florida, and after striking southern Louisiana it dissipated over the eastern United States.[1] Andrew was the first major hurricane to affect the nation since Hurricane Betsy in 1965.[2] It caused $250 million in damage (1965 USD, $384 million 2007 USD), with damage heaviest on Eleuthera and Cat Cay. Four deaths occurred due to the storm, of which one was indirectly related to the hurricane.

Preparations

At 1500 UTC on August 22, about 30 hours before landfall, the government of The Bahamas issued a hurricane watch for the northwest Bahamas, including Andros and Eleuthera islands, northward through Grand Bahama and Great Abaco. Six hours later, the watch was upgraded to a hurricane warning, and about 15 hours before landfall a hurricane warning was issued for the central Bahamas, including Cat Island, Exuma, San Salvador Island, and Long Island.[3]

In a subsequent analysis by Arthur Rolle, the Bahamas Chief Meteorological Officer, national emergency agencies including the Red Cross and the Royal Bahamas Defence Force "responded exceptionally well to the hurricane alerts." The same report cited the public "[exhibiting] a degree of complacency, particularly in New Providence and The Current, Eleuthera."[4] Ultimately, the advance warning of the hurricane contributed to the low death toll from the storm.[5] The hurricane struck four days after Hubert Ingraham became Bahamian Prime Minister, the first new Prime Minister in 25 years. There was initially a concern over how Ingraham would handle the hurricane, due to many of the government officials remaining in power from the previous administration; however, government response to the hurricane was normal.[5]

Impact

Hurricane Andrew brought hurricane-force winds, or maximum sustained wind of over 119 km/h (74 mph), to five districts – North Eleuthera, New Providence, North Andros, Bimini, Berry Islands – as well as three cays. The hurricane also produced tropical storm force winds in seven districts, including Cat Island, South Abaco, Central Andros, the northern island chain in Exuma, and the three districts on Grand Bahama.[6] Much of the northwestern Bahamas received damage,[7] with monetary damage throughout the country totaling about $250 million (1992 USD, $384 million 2008 USD).[3] The severe damage primarily occurred on sparsely populated islands, and in contrast the more populated areas largely received rainfall and gusty winds. The hurricane affected about 2% of the places available for rent in the country, resulting in a drop in tourism.[8] A total of 800 houses were destroyed, leaving 1,700 people homeless. Additionally, five schools were destroyed, and overall the storm left severe damage to the sectors of transport, communications, water, sanitation, agriculture, and fishing.[9] The hurricane caused four deaths in the country, of which three directly;[3] the indirect fatality was due to a heart failure during the passage of the storm.[4]

Hurricane Andrew first made landfall on August 23 as a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, with winds of 260 km/h (160 mph). The hurricane struck the island of Eleuthera,[1] which has a population of around 8,000,[10] and is generally about 1.6 km (0.99 mi) in width.[11] Prior to its arrival, the hurricane caused the coastline to recede about 3 mi (4.8 km), which was followed by what was described as a "mighty wall of water", or a storm surge.[5] The Current, a small village in the northwestern portion of the island, recorded a surge of 7.2 m (24 ft).[7] There, more than half of the houses in the village were destroyed, and the rest of the buildings sustained minor to major damage.[4] On nearby Current Island, the hurricane destroyed 24 of the 30 houses in the village.[4] The island's only road was heavily damaged, with parts still flooded more than a week after the storm.[5]

The hurricane was estimated to have spawned several tornadoes in Eleuthera district, based on a subsequent analysis of damage to buildings and shrubbery; tornadoes were also reported in the nearby districts of Harbour Island and Spanish Wells.[7] Towns south of where Andrew moved ashore received fairly minor damage, although the control tower at Governor's Harbour Airport was destroyed. High surf caused damage to roads and docks along the coast.[7] In Spanish Wells, located near the north coast of Eleuthera, three buildings were destroyed, and a bridge connecting to a neighboring island was wrecked. All of Harbour Island, located northeast of Eleuthera, sustained damage, with several small houses destroyed.[4] Overall, news reports indicated severe damage to 36 houses on the island.[9] One person drowned from the storm surge in Eleuthera, and two others died in nearby The Bluff.[4]

On New Providence, the hurricane destroyed one house,[4] but caused no major damage in the capital city of Nassau.[9] The Lynden Pindling International Airport near Nassau recorded 61 mm (2.4 in) of precipitation during the passage of Andrew.[6] Further west, damage on Andros Island was fairly minor and limited to the northernmost portion of the island. One dock was destroyed, and two parks were severely damaged.[6] On South Bimini, the storm caused light damage, including to two hotels on the island.[12] The private island of Cat Cay in the Bimini Islands was severely impacted by the hurricane, with damage estimated at $100 million (1992 USD). Many wealthy homes and the island's marina received heavy damage, with hundreds of trees downed by the strong winds.[8] Later, Hurricane Andrew made its second landfall in the Berry Islands early on August 24 as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[1] Damage was heavy and estimated "in the millions of dollars".[7]

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath, the Bahamas National Disaster Coordinator noted that the country did not need foreign assistance.[9] However, within hours after the storm hit, HMS Cardiff, a British Royal Navy destroyer on regular Caribbean patrol arrived, and within days a platoon of 30 British army combat engineers with Royal Signals support arrived from Belize,[9] along with supplies for rebuilding and constructing temporary shelters.[5] The British government also sent blankets and tents to distribute,[9] as well as water, food, and ice.[5] Later, other agencies sent aid to the country, including monetary assistance from the governments of Canada, Japan, and the United States, as well as the United Nations. Both the Pan American Development Foundation as well as the government sent various relief items. The American Red Cross delivered 100 tents, 100 rolls of plastic sheeting, and 1,000 cots.[9]

The passage of the hurricane disrupted several breeding colonies of the white-crowned pigeon throughout the country.[4] Though the hurricane did not affect many tourist areas, officials predicted a decline in tourism by up to 20% in the months after the storm.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Ed Rappaport (2005-02-07). "Hurricane Andrew Report Addendum". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (1)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- 1 2 3 Ed Rappaport (1993). "Hurricane Andrew Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (4)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jonathan Freedland (1992-09-02). "Storm Ravaged Island in Bahamas". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- 1 2 3 Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (2)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (3)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- 1 2 3 Edwin McDowell (1992-09-27). "After the storms: Three reports; Bahamas". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (1992). "Bahamas and U.S.A. - Hurricane Andrew Aug 1992 UN DHA Information Reports 1-3". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ Commonwealth of the Bahamas (2005). "Eleuthera Island Information". Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Embassy of the United States - Bahamas. "Bahamas Information". Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Carl Sommers (1993-01-10). "Q & A". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-07.