| Qattara Depression | |

|---|---|

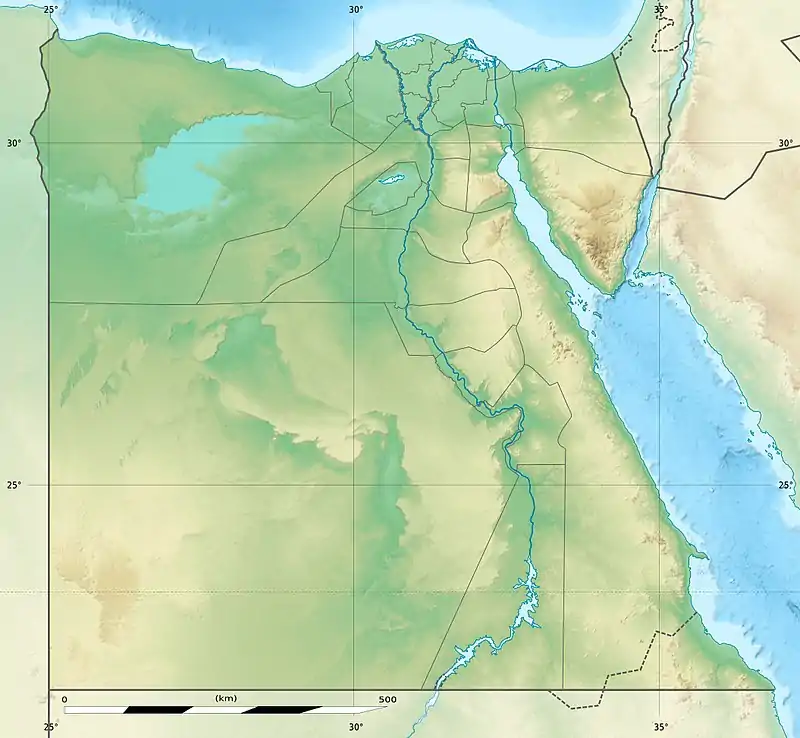

Qattara Depression Location of the Qattara Depression in Egypt | |

| Location | Egypt in the Matruh Governorate |

| Coordinates | 30°0′N 27°30′E / 30.000°N 27.500°E |

| Type | Endorheic basin |

| Primary inflows | Groundwater |

| Primary outflows | Evaporation |

| Basin countries | Egypt |

| Max. length | 300 kilometres (190 mi) |

| Max. width | 135 kilometres (84 mi) |

| Surface area | 19,605 square kilometres (7,570 sq mi) |

| Average depth | −60 metres (−200 ft) |

| Max. depth | −133 metres (−436 ft) |

| Water volume | 1,213 cubic kilometres (291 cu mi) |

| Settlements | Qara Oasis |

| References | [1][2] |

The Qattara Depression (Arabic: منخفض القطارة, romanized: Munḫafaḍ al-Qaṭṭārah) is a depression in northwestern Egypt, specifically in the Matruh Governorate. The depression is part of the Western Desert of Egypt. The Qattara Depression lies below sea level, and its bottom is covered with salt pans, sand dunes, and salt marshes. The depression extends between the latitudes of 28°35' and 30°25' north and the longitudes of 26°20' and 29°02' east.[3]

The Qattara Depression was created by the interplay of salt weathering and wind erosion. Some 20 kilometres (10 mi) west of the depression lie the oases of Siwa in Egypt and Jaghbub in Libya in smaller but similar depressions.

The Qattara Depression contains the second lowest point in Africa at an elevation of 133 metres (436 ft) below sea level, the lowest point being Lake Assal in Djibouti. The depression covers about 19,605 square kilometres (7,570 sq mi), a size comparable with Lake Ontario or twice as large as Lebanon. Due to its size and proximity to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, studies have been made proposing to flood the area for various usages, such as the potential to generate hydroelectricity there.

Geography

Lower left bound: 28°36'30.74"N 26°14'31.08"E.

Upper right bound: 30°31'1.74"N 29° 8'51.83"E.

The Qattara Depression has the shape of a teardrop, with its point facing east and the broad deep area facing southwest. The northern side of the depression is characterised by steep escarpments up to 280 m (920 ft) high, marking the edge of the adjacent El Diffa plateau. To the south the depression slopes gently up to the Great Sand Sea.

Within the Depression are salt marshes, under the northwestern and northern escarpment edges, and extensive dry lake beds that flood occasionally. The marshes occupy approximately 300 square kilometres (120 sq mi), although wind-blown sands are encroaching in some areas. About a quarter of the region is occupied by dry lakes composed of hard crust and sticky mud, and occasionally filled with water.

The depression was initiated by either wind or fluvial erosion in the late Neogene, but during the Quaternary Period the dominant mechanism was a combination of salt weathering and wind erosion working together. First, the salts break up the depression floor, then the wind blows away the resulting sands. This process is less effective in the eastern part of the depression, due to lower salinity groundwater.[4]

Ecology

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Groves of umbrella thorn acacia (Vachellia tortilis), growing in shallow sandy depressions, and Phragmites swamps represent the only permanent vegetation. The acacia groves vary widely in biodiversity and rely on runoff from rainfall and groundwater to survive. The Moghra Oasis in the northeastern part of the Depression has a 4 km2 (1.5 sq mi) brackish lake and a Phragmites swamp.[5][6]

The southwestern corner of the depression is part of the Siwa Protected Area which protects the wild oasis in and around the Siwa Oasis.

The Depression is an important habitat for the cheetah, with the largest number of recent sightings being in areas in the northern, western and northwestern part of the Qattara Depression, including the highly isolated, wild oases of Ain EI Qattara and Ein EI Ghazzalat and numerous acacia groves both inside and outside the depression.[7]

Gazelles (Gazella dorcas and Gazella leptoceros) also inhabit the Qattara Depression, being an important food source for the cheetah. The largest gazelle population exists in the southwestern part of the Qattara Depression within a vast area of wetlands and soft sand. The area of 900 km2 (350 sq mi), includes the wild oases of Hatiyat Tabaghbagh and Hatiyat Umm Kitabain, and is a mosaic of lakes, salt marshes, scrubland, wild palm groves and Desmostachya bipinnata grassland.[7]

Other common fauna include the Cape hare (Lepus capensis), Egyptian jackal (Canis aureus hupstar), sand fox (Vulpes rueppelli) and more rarely the fennec fox (Vulpes zerda). Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) were once common here but now they are few in number.

Extinct species from the area include the scimitar oryx (Oryx dammah), addax (Addax nasomaculatus) and bubal hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus).[8] Also the Droseridites baculatus, an extinct plant known only from fossils of its pollen, was found at the Ghazalat-1 Well.[9]

Climate

The climate of the Qattara Depression is highly arid with annual precipitation between 25 and 50 mm (0.98 and 1.97 in) on the northern rim to less than 25 mm (0.98 in) in the south of the depression. The average daily temperature varies between 36.2 to 6.2 °C (97.2 to 43.2 °F) during summer and winter months. The prevailing wind forms a largely bimodal regime with most wind coming from north easterly and westerly directions. This causes the linear dune formations in the Western desert between the Qattara Depression and the Nile valley. Wind speeds peak in March at 11.5 m/s (26 mph) and minimal in December at 3.2 m/s (7.2 mph).[4] The average wind speed is about 5 to 6 m/s (11 to 13 mph).[10] Several days each year in the months March to May khamsin winds blow in from the south and bringing extremely high temperatures as well as sand and dust with them.

Land use

There is one permanent settlement in the Qattara Depression, the Qara Oasis. The oasis is located in the westernmost part of the depression and is inhabited by about 300 people.[11] The Depression is also inhabited by the nomadic Bedouin people and their flocks, with the uninhabited Moghra Oasis being important in times of water scarcity during the dry seasons.

The Qattara Depression contains many oil concessions, and several operational oil fields. The drilling companies include Royal Dutch Shell and the Apache Corporation.

History

Measurement

The elevation of the depression was first measured in 1917 by an officer of the British Army leading a light car patrol into the region. The officer took readings of the height of the terrain with an aneroid barometer on behalf of John Ball, who later would also publish on the region. He discovered that the spring Ain EI Qattara lay about 60 metres (200 ft) below sea level. Because the barometer got lost and the readings were so unexpected, this find had to be verified. During 1924–25, Ball again organised a survey party, this time with the sole purpose to triangulate the elevation on a westerly line from Wadi El Natrun. The survey was led by G.F. Walpole who had already distinguished himself by triangulating the terrain across 500 km (310 mi) from the Nile to Siwa via Bahariya. He confirmed the earlier readings and proved the presence of a huge area below sea level, with places as deep as 133 m (436 ft) below sea level.[3]

Knowledge about the geology of the Qattara Depression was greatly extended by Ralph Alger Bagnold, a British military commander and explorer, through numerous journeys in the 1920s and 1930s. Most notable was his 1927 journey during which he crossed the depression east to west and visited the oases of Qara and Siwa. Many of these trips used motor vehicles (Ford Model-Ts) which used special techniques for driving in desert conditions. These techniques were an important asset of the Long Range Desert Group which Bagnold founded in 1940.[12]

After the discovery of the depression, Ball published the triangulation findings about the region in October 1927 in The Geographical Journal. He also gave the region its name "Qattara" after the spring Ain EI Qattara where the first readings were taken. The name literally means "dripping" in Arabic. Six years later in 1933, Ball was the first to publish a proposal for flooding the region to generate hydroelectric power in his article "The Qattara Depression of the Libyan Desert and the possibility of its utilisation for power-production".[3]

World War II

During World War II, the depression's presence shaped the First and Second Battles of El Alamein. It was considered impassable by tanks and most other military vehicles because of features such as salt lakes, high cliffs and/or escarpments, and fech fech (very fine powdered sand). The cliffs in particular acted as an edge of the El Alamein battlefield, which meant the British Empire's forces could not be outflanked to the south. Both Axis and Allied forces built their defences in a line from the Mediterranean Sea to the Qattara Depression. These defences became known as the Devil's gardens, and they are for the most part still there, especially the extensive minefields.

No large army units entered the Depression, although German Afrika Korps patrols and the British Long Range Desert Group did operate in the area, since these small units had considerable experience in desert travel.[12][13] The RAF's repair and salvage units (e.g. 58 RSU) used a route through the depression to salvage or recover aircraft that had landed or crashed in the Western desert away from the coastal plain.

The RSUs included six-wheel-drive trucks, Coles cranes, and large trailers, and were particularly active from mid-1941 when Air Vice-Marshal G.G. Dawson arrived in Egypt to address the lack of serviceable aircraft.[14]

A German communications officer stationed in the depression was cited by Gordon Welchman as being unintentionally helpful in the breaking of the Enigma machine code, due to his regular transmissions stating there was "nothing to report".[15]

Qattara Depression Project

The large size of the Qattara Depression and the fact that it falls to a depth of 133 m (436 ft) below mean sea level has led to several proposals to create a massive hydroelectric power project in northern Egypt rivalling that of the Aswan High Dam. This project is known as the Qattara Depression Project. The proposals call for a large canal or tunnel being excavated from the Qattara due north of 55 to 80 kilometres (34 to 50 mi) depending on the route chosen to the Mediterranean Sea to bring seawater into the area.[16]

An alternative plan involved running a 320-kilometre (200 mi) pipeline northeast to the freshwater Nile River at Rosetta.[17][18] Water would flow into a series of water penstocks which would generate electricity by releasing the water at 60 m (200 ft) below sea level. Because the Qattara Depression is in a very hot dry region with very little cloud cover, the water released at the −70 metres (−230 ft) level would spread out from the release point across the basin and evaporate from solar influx. Because of evaporation, more water can flow into the depression, thus forming a continual source of power. Eventually this would result in a hypersaline lake or a salt pan as the water would evaporate and leave behind the salt that it contained.

Plans to use the Qattara Depression for the generation of electricity date back to 1912 from Berlin geographer Albrecht Penck.[19] The subject was discussed in more detail by Dr. John Ball in 1927, who estimated a hydroelectric potential of 125 to 200 megawatts.[20] In 1957, the American Central Intelligence Agency proposed to President Dwight Eisenhower that peace in the Middle East could be achieved by flooding the Qattara Depression. The resulting lagoon, according to the CIA, would have four benefits:[21]

- it is easier to extract oil from offshore platforms than in swamps

- the flow will turn the hydroelectric power station

- fishing, resorts, pearls

- It would get Egyptian president Gamel Abdel Nasser's "mind on other matters" because "he need[ed] some way to get off the Soviet hook"

In the 1970s and early 1980s, several proposals to flood the area were made by Friedrich Bassler and the Joint Venture Qattara, a group of mainly German companies. They wanted to make use of peaceful nuclear explosions to construct a tunnel, drastically reducing construction costs compared to conventional methods. This project proposed to use 213 H-bombs, with yields of one to 1.5 megatons, detonated at depths of 100 to 500 metres (330 to 1,640 ft). That fit within the Atoms for Peace program proposed by US President Dwight Eisenhower in 1953. The Egyptian government turned down the idea.[22]

Planning experts and scientists intermittently put forward potentially viable options, whether of a tunnel or canal, as an economic, ecological, and energy solution in Egypt, often coupled with the idea of new settlements.[22][23][24]

References

- ↑ Dr. Andrew, J. 2007. Report on the Qattara Depression CIAT Land Use project

- ↑ Ball, John (1933). "The Qattara Depression of the Libyan Desert and the Possibility of Its Utilization for Power-Production". The Geographical Journal. 82 (4): 289–314. doi:10.2307/1785898. JSTOR 1785898.

- 1 2 3 El Bassyony, Abdou. 1995. "Introduction to the geology of the Qattara Depression," International Conference on the Studies and Achievements of Geosciences in Egypt, 69 (85-eoa)

- 1 2 Aref, M.A.M.; El-Khoriby, E.; Hamdan, M.A. (2002). "The role of salt weathering in the origin of the Qattara Depression, Western Desert, Egypt". Geomorphology. 45 (3–4): 181–195. Bibcode:2002Geomo..45..181A. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00152-0.

- ↑ Hughes, R. H. and J. S. Hughes. 1992. A Directory of African Wetlands. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN 2-88032-949-3.

- ↑ Nora Berrahmouni and Burgess, Neil. 2001. "Saharan halophytics". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- 1 2 Saleh, M.A.; Helmy, I.; Giegengack, R. (2001). "The Cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus (Schreber, 1776) in Egypt (Felidae, Acinonychinae)". Mamm. 65 (2): 177–194. doi:10.1515/mamm.2001.65.2.177. S2CID 84527196.

- ↑ Manlius, Nicolas; Menardi‐Noguera, Alessandro; Zboray, Andras (2003). "Decline of the Barbary sheep ( Ammotragus lervia ) in Egypt during the 20th century: Literature review and recent observations". Journal of Zoology. 259 (4): 403–409. doi:10.1017/S0952836902003394.

- ↑ Ibrahim, M.I.A. (1996). "Aptian-Turonian palynology of the Ghazalat-1 Well (GTX-1), Qattara Depression, Egypt". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 94 (1–2): 137–168. Bibcode:1996RPaPa..94..137I. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(95)00135-2.

- ↑ Mortensen, N. G.; Said, U.S.; Badger, J. (2006). Wind Atlas for Egypt: Measurements, Micro- and Mesoscale Modeling. New and Renewable Energy Authority, Cairo, Egypt

- ↑ Kjeilen, Tore Looklex report on the Qara oasis Archived 14 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, date unknown

- 1 2 Bagnold, R. A. (1931). "Journeys in the Libyan Desert, 1929 and 1930". The Geographical Journal. 78 (1): 13–33. doi:10.2307/1784992. JSTOR 1784992.

- ↑ Jorgensen, C. (2003). Rommel's panzers: Rommel and the Panzer forces of the Blitzkrieg, 1940–1942 (pp. 78–79). St. Paul, MN: MBI.

- ↑ Richards, D., Saunders, H. (1975). Royal Air Force 1939-45 Vol II (pp 160-167). Stationery Office Books

- ↑ Lee, Lloyd (1991). WWII: Crucible of the Contemporary World : Commentary and Readings. M.E. Sharpe. p. 240. ISBN 9780873327312.

- ↑ Ragheb, M. 2010. Pumped Storage Qattara Depression Solar Hydroelectric Power Generation.pdf "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Published on 28 October 2010. - ↑ Mahmoud, Mohamed. The River Nile - Qattara Depression Pipeline, June 2009

- ↑ User:TGCP Great Circle Mapper - Rosetta to Qattara, 2011

- ↑ Murakami, Masahiro (1995). Managing water for peace in the Middle East (PDF). United Nations University Press. pp. 64–66. ISBN 92-808-0858-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012.

- ↑ Ball, John (1927). "Problems of the Libyan Desert". The Geographical Journal. 70 (1): 21–38. doi:10.2307/1781881. JSTOR 1781881.

- ↑ MI: Gale. 2009. Farmington Hills, CIA Suggestions, Document Number CK3100127026. Reproduced in "Declassified Documents Reference System"

- 1 2 Hafiez, Ragab A. (2010). "Mapping of the Qattara Depression, Egypt, using SRTM Elevation Data for Possible Hydropower and Climate Change Macro-Projects". Macro-engineering Seawater in Unique Environments. Environmental Science and Engineering. pp. 519–531. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14779-1_23. ISBN 978-3-642-14778-4.

- ↑ Baghdadi, A.H.A.; Mobarak, A. (1989). "A Feasibility Study for Power Generation from the Qattara Depression using a Hydro-Solar Scheme". Energy Sources. 11: 39–52. doi:10.1080/00908318908908939.

- ↑ Kelada, Maher. Global Hyper Saline Power Generation Qattara Depression Potential MIK Technology

- Antonio Mascolo Die Kattara-Utopie http://www.kattara-utopie.de

Further reading

- Annotations. Central University Libraries at Southern Methodist University. Vol. VI, No. 1, Spring 2004.

- Bagnold, R. A. (1933). "A Further Journey Through the Libyan Desert". The Geographical Journal. 82 (2): 103–126. doi:10.2307/1785658. JSTOR 1785658.

- Bagnold, R.A. 1935. Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World. Travel Book Club, London. 351 p.

- Bagnold, R.A. (1939). "A lost world refound". Scientific American. 161 (5): 261–263. Bibcode:1939SciAm.161..261B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1139-261.

- Eizel-Din, M. A.; Khalil, M. B. (2006). "Development potential: Evaluation of the hydro-power potential of Egypt's Qattara Depression". International Water Power and Dam Construction. 58 (10): 32–36.

- Hassanein Bey, A.M. (1924). "Crossing the untraversed Libyan Desert". The National Geographic Magazine. 46 (3): 233–277. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Ramsar Sites Information Service (RSIS). Egypt. Accessed 21 August 2011.

- Rohlfs G. 1875. Drei Monate in der Libyschen Wüste (Three Months in the Libyan Desert). Verlag von Theodor Fischer, Cassel. 340 p.

- Saint-Exupéry, A. de. 1940. Wind, Sand and Stars. Harcourt, Brace & Co, New York.

- Scott, C. 2000. Sahara Overland: A Route and Planning Guide. Trailblazer Publications. 544 p. ISBN 978-1-873756-76-8.

- Zittel, K.A. von. 1875. Briefe aus der libyschen Wüste (Letters from the Libyan Desert). München.