| The Princess of Belvedere | |

|---|---|

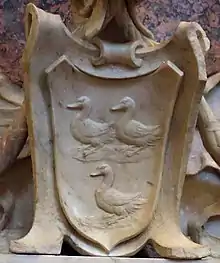

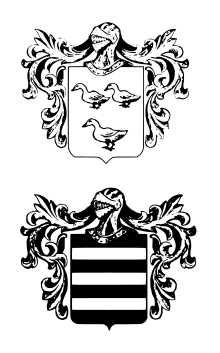

Arms of Van den Eynde | |

| Born | 14 April 1674 Naples |

| Died | 14 February 1743 (aged 68) Naples |

| Spouse | Carlo Carafa, 3rd Prince of Belvedere, 6th Marquess of Anzi, and Lord of Trivigno |

| Issue | Francesco Maria Carafa, 4th Prince of Belvedere, 7th Marquess of Anzi and Baron of Trivigno, Bonifati, Mottafollone and San Sosti[1] Giovanna Carafa, nun of the order of Santa Maria Donna Regina Vecchia[1] |

| House | Van den Eynde |

| Father | Ferdinand van den Eynde, 1st Marquess of Castelnuovo |

| Mother | Olimpia Piccolomini |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Elisabeth van den Eynde, Princess of Belvedere (also spelled Vandeneinden,[2] Vandeneynden,[3] Van den Eynden,[4] and Van den Einden[5]) and suo jure Baroness of Gallicchio and Missanello[1] (14 April 1674 – 14 February 1743) was an Italian noblewoman.[6][1] She was the consort of Carlo Carafa, 3rd Prince of Belvedere, 6th Marquess of Anzi, and Lord of Trivigno, and the daughter of Ferdinand van den Eynde, 1st Marquess of Castelnuovo and Olimpia Piccolomini, of the House of Piccolomini. Her grandfather was Jan van den Eynde, a wealthy Flemish merchant, banker and art collector who purchased and renovated the Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano in 1653. Her father Ferdinand, the Marquess of Castelnuovo, built the Vandeneynden Palace of Belvedere between 1671 and 1673. While the Palazzo Zevallos in central Naples passed to her elder sister Giovanna, who married a Colonna heir, Elisabeth was given the monumental Palazzo Vandeneynden, alongside a smaller portion of the Marquess' assets, which included his art collection, one of the largest and most valuable in Naples and its surroundings.[7] Upon her marriage to Carlo Carafa, the Vandeneynden Palace came to be known as Villa Carafa.[8][9]

Family

Elisabeth was born into the Van den Eynde family, a powerful and influential Neapolitan noble family of Flemish origin, related to several prominent Flemish artists, including Brueghel, Jode, Lucas de Wael and Cornelis de Wael.[10][11][12] Her father was Ferdinand van den Eynde, 1st Marquess of Castelnuovo, the son of Jan van den Eynde, a wealthy merchant from Antwerp, who became one of the richest and most prominent men in Naples.[13][6] The Marquess Ferdinand married Olimpia Piccolomini, of the House of Piccolomini, a nephew of Cardinal Celio Piccolomini, by whom he had three daughters, Catherine, the eldest, Giovanna, the secondborn, and Elisabeth.[2][13]

In 1674, her father the Marquess inherited his father's Jan impressive art collection. He also inherited a sizable collection of 70[14] or 90[4] paintings from his longtime friend and business partner Gaspar Roomer.[13][15] Marquess Ferdinand, however, died that same year,[4] and his collection, together with his assets, were split between his infant daughters, Giovanna and Elisabeth[13] (according to some sources, his eldest daughter, Catherine, was later judged incapacitated[16][2]). Van den Eynde's assets were frozen until his daughters reached adulthood and married.[16] Luca Giordano, another longtime friend of Van den Eynde, took care of the inventory for Van den Eynde's inheritance.[16] While drawing up the inventory, Giordano counted ten paintings executed by himself in Van den Eynde's collection.[16]

Marriage

On April 11, 1688,[1] just three days before her fourteenth birthday, she was married to her agemate Carlo Carafa, 3rd Prince of Belvedere, 6th Marquess of Anzi, and Lord of Trivigno. Carlo was a Carafa, one of the most powerful families in Italy. Through her marriage to Carlo, Elisabeth became part of the House of Carafa, and Princess consort of Belvedere. Carlo Carafa, on the other hand, received a huge dowry,[17] and inherited the Palazzo Vandeneynden, which thereafter became Villa Carafa.[8][9]

Baroness of Gallicchio and Missanello

In 1689, Princess Elisabeth bought the fiefs of Gallicchio, Missanello, and Castiglione, whose proprietor, Gian Battista Pignatelli, was in financial trouble. Upon inheriting the fiefs from his mother, Beatrice Carafa De Lannoy, mother of Elisabeth's father-in-law Don Francesco Maria Carafa (Pignatelli being the son of a third marriage), Pignatelli's brothers contested the will, together with a Di Stefano, who claimed over fifteen thousand ducats from Pignatelli, out of debts Pignatelli's ancestors had to his own family. Pignatelli was able to satisfy his brothers, but not Di Stefano. Four years after his commitment to pay what was due to Di Stefano, the latter seized the fiefs, as Pignatelli had not been able to repay him. The fiefs were then sold to Princess Elisabeth, whose father-in-law, as mentioned, was the half-brother of Pignatelli.[6]

Elisabeth governed the fiefs together with her son Francesco Maria Carafa via stewards, for over thirty years. She sold the fiefs on August 26, 1736. Some sources claim the contract was signed on August 26, 1732,[18] possibly due to confusion over the last digit. However, there is enough circumstantial evidence to support the 1736 dating.[6]

When, in 1735, the new King of Naples and Sicily Charles III of Spain undertook a journey through Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, and Sicily, in order to assess the condition of his kingdom and its people, he was shocked by the poor living conditions of the population and the overall cultural and economic backwardness in those lands. He therefore disposed an inquiry, requiring a detailed description of the territory, the so-called Relazione Gaudioso, completed in 1736. As regards Gallicchio, it was reported that "The land of Gallicchio [...] is possessed by the illustrious Princess Belvedere, with a revenue of ca. 300 ducats, which she derives from both the feudal and the allodal."[18][6] Further, when in 1737 Niccolò Parrino printed in Naples the first translation into Calabrian of Tasso's Gerusalemme liberata, he dedicated it to the "Most excellent Lord Don Francesco Maria Carafa, Prince of Belvedere, Prince of Gallicchio, and Marquess of Anzi [...]."[6] The Golden Book of Italian nobility indicates 1737 as the year of the end of Elisabeth's barony in Gallicchio.[1]

Issue

Princess Elisabeth and Prince Carlo Carafa had one son and a daughter.

- Francesco Maria Carafa, 4th Prince of Belvedere, 7th Marquess of Anzi and Baron of Trivigno, Bonifati, Mottafollone and San Sosti[1]

- Giovanna Carafa, Nun of the order of Santa Maria Donna Regina Vecchia[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Libro d'Oro della Nobiltà Mediterranea". Comitato Scientifico Scientifico Editoriale del Libro d'Oro della Nobiltà Mediterranea. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 Aldimari, Biagio (1691). Historia genealogica della famiglia Carafa pt 2. Stamperia di Giacomo Raillard. p. 314.

- ↑ Tzeutschler Lurie, Ann (1984). Bernardo Cavallino of Naples, 1616-1656. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 245. ISBN 9780910386753.

- 1 2 3 Bissell, Roger Ward (1999). Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780271017877.

- ↑ Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. (1999). Jusepe de Ribera 1591-1652. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 77, 78, 288. ISBN 9780870996474.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Maria Grazia Lanzano. "6. Dai Coppola ai Lentini". Dizionario Dialettale di Gallicchio. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ↑ Cristina Trimarchi. "RUBENS, VAN DYCK E RIBERA: TRE GRANDI ARTISTI IN UN'UNICA PRESTIGIOSA ESPOSIZIONE A NAPOLI". Classicult. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- 1 2 Attanasio, Sergio (1985). La Villa Carafa di Belvedere al Vomero. Napoli SEN. pp. 1–110.

- 1 2 La Gala, Antonio (2004). Vomero. Storia e storie. Guida. pp. 5–150.

- ↑ "Rubens, Van Dyck, Ribera: 36 capolari in mostra a Palazzo Zevallos". Il Mattino. 5 December 2018.

Stretti rapporti di parentela legavano la famiglia Vandeneynden a quelle di diversi artisti fiamminghi (i Brueghel, i de Wael, i de Jode)

- ↑ "Mediterranean Masterpieces - This Collection Tells the Story of Naples Through Its Art". Vice Media. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ Stoesser, Alison (2018). Tra Rubens e van Dyck: i legami delle famiglie de Wael, Vandeneynden e Roomer. pp. 41–49.

- 1 2 3 4 Ruotolo, Renato (1982). Mercanti-collezionisti fiamminghi a Napoli: Gaspare Roomer e i Vandeneynden. Massa Lubrense Napoli - Scarpati. pp. 5–55.

- ↑ Berision, A. (1970). Napoli nobilissima. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia. pp. 161–164.

- ↑ G.Porzio, G.J. van der Sman (2018). 'La quadreria Vandeneynden' 'La collezione di un principe'. A. Denunzio. pp. 51–76.

- 1 2 3 4 De Dominici, Bernardo; Sricchia Santoro, Fiorella; Zezza, Andrea. Vite de' pittori- Dominici. Paparo Edizioni. pp. 772, 773.

- ↑ Bellori, Gian Pietro (1672). The Lives of the Artists (Bellori). Rome, Italy: Moscardi. p. 31.

- 1 2 Sanchirico, Mario (2009). Gallicchio. Società e vita politico-amministrativa (dalle origini all'Unità). Potenza.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)