Elise Mercur | |

|---|---|

Mercur, 1896 | |

| Born | November 30, 1864 Towanda, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | March 27, 1947 (aged 82) Sewickley, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Elise Mercur Wagner |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Years active | 1890–1905 |

| Notable work | The Women's Building, Cotton States and International Exposition (1895) |

| Spouse | Karl Rudolph Wagner |

| Children | 1 |

Elise Mercur, also known as Elise Mercur Wagner (November 30, 1864 – March 27, 1947), was Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania's first female architect. She was raised in a prominent family and educated abroad in France and Germany before completing training as an architect at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her first major commission, for the design of the Woman's Building for the Cotton States and International Exposition of Atlanta, was secured in 1894, while she was apprenticed to Thomas Boyd. It was the first time a woman had headed an architectural project in the South. After completing a six-year internship, she opened her own practice in 1896, where she focused on designing private homes and public buildings, such as churches, hospitals, schools, and buildings for organizations like the YMCA/YWCA.

Mercur was a popular lecturer and not only designed, but supervised the construction of her projects. In 1897, she designed the Marshalsea Poor Farm hospital for children in Bridgeville, Pennsylvania and her design of the Washington Female Seminary building led by contractor Clara Meade was completed in 1898. Before she retired in 1905, Mercur designed over a dozen projects, many of which have since been demolished. St. Paul Episcopal Church (1896) at 2601 Center Avenue in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, designed by Mercur, was recognized by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation as a historic landmark.

Early life and education

Elise Mercur was born November 30, 1864[Notes 1] in Towanda, Bradford County, Pennsylvania, to Anna Hubbard (née Jewett) (1832–1901) and Mahlon Clark Mercur (1916–1905).[3][10][11] Her mother was a poet from Bolton, Massachusetts,[11] and her father, from Bradford County, was a prominent Pittsburgh banker, businessman, and councilman.[12] She had five siblings: Robert Jewett (1854–1929), Helen (1854–1929), Annie E., William H., and Hiram (1861–1918) and a half-brother, Mahlon, from her father's first marriage.[3][10] She was the niece of Ulysses Mercur, Chief Justice of Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chief Justice (1883–1888).[11] Mercur was educated in France and in Stuttgart, Germany, where she studied art, mathematics, languages, and music, becoming fluent in French and German.[11][13] She returned to the United States where she studied design at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for three years.[13][14]

Architecture career

In 1890, Mercur began to work as a technical illustrator, and was promoted within a year to construction foreman in the Pittsburgh office of a prominent Pittsburgh architect, Thomas Boyd.[15][16][17] In 1894, she competed against 13 other women architects in the design of the Woman's Building for the Cotton States and International Exposition to be held in Atlanta. In a unanimous decision, for her first major commission, she was awarded the $100 prize.[18][19][20] After completing a six-year apprenticeship with Boyd, she opened her own architectural practice in 1896 in the Pittsburgh Westinghouse Building, where she was commissioned to design homes throughout western Pennsylvania.[14][21] That year, she became a founding member of Pittsburgh's Architectural Club at Twentieth Century Club of Lansdowne, serving as the organization's first treasurer.[22] A popular lecturer, Mercur delivered talks on a range of architectural topics, including construction processes, sanitation, and ventilation, at various clubs and educational facilities like the Pratt Institute School of Architecture of Brooklyn.[16][23][24]

Mercur, who was primarily commissioned to design public buildings and private homes, advertised her architectural plans in the Sunday edition of the Pittsburgh Post.[14][25] In 1897, she was hired by the City of Pittsburgh to make plans and specifications for the Department of Charities for the design of the Children's Building to be erected at City Home and Hospital, Marshalsea.[26] That year, she was also hired to add a new wing to the Washington Female Seminary on Lincoln Street in Washington, Pennsylvania.[27][28] In 1898, Mercur moved her practice to the Times Building on 4th Avenue in Pittsburgh,[15] where she employed three draughtsmen to assist with her work.[16] On October 1 she married Karl Rudolph Wagner (1872–1949), a German immigrant living in Economy, Pennsylvania.[29][30] The couple were married in the home of Mercur's brother and services were officiated by the rector Robert Maddington Grange of the Church of the Ascension.[29]

Of her decision to work in the male-dominated field of architecture, Mercur stated in an interview with The New York World that after her father had lost his fortune and died, she did not want to be dependent on her family. She also noted that she demanded and was paid the same fees that male architects received for their work.[16] The April 1898 issue of Home Monthly praised her attention to detail and noted her habit of living near the construction site to ensure she could properly supervise the building project. It introduced Mercur to readers in her role as an architect on the job at a construction site:[15]

She goes out herself to oversee the construction of the buildings she designs, inspecting the laying of foundations and personally directing the different workmen from the first stone laid to the last nail driven, thereby acquiring a practical knowledge not possessed by every male architect.[31]

In 1899, Wagner was listed on the Interstate Architects and Builders list of "Leading Architects in the Seven States"[31] and she became known as the first woman architect to bring suit in the Pittsburgh Common Court for Pleas to recover architects fees.[32] She moved her office to Economy in 1900,[31] and began remodeling a home in Old Economy Village for herself and her husband.[33] In 1904, Wagner built a private home and two schools in Economy.[34] She retired the following year, after injuring her back in an accident.[35][36]

Later life and legacy

The Wagners' only child,[Notes 2] Johannes Eberhardt Wagner, known as Hans, was born on October 2, 1912[30][37] and served in the US Army during World War II.[35] In 1924, Wagner published a history of the towns of Old Economy Village and Ambridge Pennsylvania for the Harmony Society's centennial celebrations.[33] She died on March 26 or 27, 1947 in Sewickley Valley Hospital in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, and was buried in the Economy Cemetery on Ridge Road, Ambridge, Pennsylvania.[35][38]

Mercur (Wagner) is recognized as a pioneering woman architect, who made significant contributions in the Pittsburgh area.[16][15] The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation calls her "the region's first woman architect".[39] She is best known for her design of the Women's Building for the Cotton States Exhibition in 1895.[15] Her design plans for the dome of the structure which were still being used in construction guidelines over a decade later.[40] In 2007, the building she designed in 1896 as St. Paul's Episcopal Church was designated as a historic landmark by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. It is now Christian Tabernacle Kodesh Church of Immanuel and is located at 2601 Centre Avenue, Pittsburgh.[39]

Major works

Woman's Building

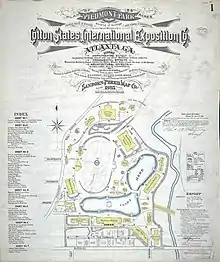

In 1894, Mercur entered a design competition for the 1895 International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia.[41] In a unanimous decision, she was awarded the commission over 13 other entries.[18] Her selection proved beneficial for the planners, as she was able to secure structural materials from Carnegie Steel Company.[19] Her proposal included a plastered, two-story frame building over a finished basement of brick and iron adorned with a tin roof topped by a dome. The building was to have four staircases, one of which gave access to the roof. It also contained men's and women's lavatories in the basement, a kindergarten area, fireplaces in each room, and a kitchen with a restaurant.[18] When news of her win was announced, it marked the first time that a woman's design was selected for any major building project in the South.[36] Minor modifications to her original plans were made during construction to remain within budget.[19]

The Women's Building was one of 13 exhibition buildings arranged around a 13-acre (5.3 ha) central lake.[42][43] The Palladian style structure featured a raised basement. The entrance was behind a portico featuring five bays supported by Corinthian columns and measured 128 by 150 feet (39 by 46 m).[42][44] Mercur designed a four square elevation topped by a dome which rose 90 feet (27 m) from the floor. The dome was surmounted by a statue of a woman holding a torch, representing female enlightenment.[42][45] Painted pale yellow and white,[45] the exterior presented a grand stair and ornamental friezes, cornices; and balustrades encircling the roof. Mounted statues on ornamental pedestals "symbolic of woman and her power" adorned the roof.[36][42] Visitors to the Women's Building entered through a soaring central hall, flanked by a grand double stair, in a natural wood finish. The interior composition of well-lit, airy rooms housed the exhibits, which included Colonial artifacts, women's fine art works, and a library of books written by women. It also contained a hospital, nursery, model school, and a fireproof room.[46][45] The building was described in the event program as a "diamond among jewels" and stood until 1910, when it was razed to allow the construction of Piedmont Park.[36][42]

Children's Building

In 1897, Mercur designed a hospital for children at the Marshalsea Poor Farm (later renamed Mayview State Hospital) in Bridgeville, Pennsylvania. At the time of commission, the hospital did not have a separate facility for sick children, who were instead admitted to the women's dormitory. Mercur's design for the Marshalsea Poor Farm was a one-story brick building measuring 48 by 64 feet (15 by 20 m), trimmed in stone. Four pillars support a front portico. The interior design provided a large central sitting room, six sleeping areas with approximately one hundred beds, a separate area for the nurses' rooms, and another for dining.[47] The buildings at the Poor Farm, which had become a psychiatric facility and home for the indigent were damaged by fire in 1907. Mercur's building was later demolished,[31] though the institution remained open until 2008.[48][49]

Washington Female Seminary

Washington Female Seminary was a Presbyterian seminary for women in Washington, Pennsylvania, established in 1836.[50] In 1896, the school began exploring the possibility of relocating to a new site, but it was finally determined the costs were excessive and a contract was made with Mercur to build a new building for the school on its existing site on East Maiden and South Lincoln Streets.[51][52][53] Built in a Roman classical style, the structure featured buff-colored brick and stone arranged with a four-story main building flanked by two large wings framing a rear courtyard. The east wing housed a 47 by 50 feet (14 by 15 m) assembly room; the face of the main building ran for 170 feet (51.82 m) on Maiden and 125 feet (38.10 m) on Lincoln. The west wing contained administrative offices and quarters, a reception area and parlor, the dining room, and the kitchen. The gymnasium, laboratory, and four classrooms made up the first floor. On the second floor were five classrooms while the third floor contained an atelier, as well as a music and practice rooms. The fourth floor was reserved for resident housing.[53] The contractor for the design was Clara Meade of Chicago, who had learned her trade from her father.[54] Construction was completed in 1898.[55]

In 1939, the female seminary was sold to Washington & Jefferson College,[56] which subsequently renamed the building designed by Mercur as McIlvaine Hall, after alumni Judge John Addison McIlvaine.[31][57] In 2008, the McIlvaine Hall was razed and a science building was erected on the site.[31][58] Shortly before the demolition, President Tori Haring-Smith toured a group of alumni through Mercur's building.[58]

Other selected works

- 1895: Beaver College and Musical Institute, College Avenue at Turnpike Street, Beaver, Pennsylvania.[14][31]

- 1896: Colonial residence, Beaver, Pennsylvania.[14]

- 1896: St. Paul's Episcopal Church, (renamed Christian Tabernacle Kodesh Church of Immanuel), 2601 Center Avenue, the Hill, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[31][39]

- 1896: Clubhouse for the Twentieth Century Club of Pittsburgh.[59]

- 1897: St. Martin's Episcopal Church, Johnsonburg, Pennsylvania, razed 1965.[31][16]

- 1897: The McCullough Building, Penn Avenue and 7th Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[60]

- 1897: Y.W.C.A., Syracuse, New York, a 6-story building with an estimated cost of $100,000.[61]

- 1897: Y.W.C.A. at Penn Avenue and 5th Street, Pittsburgh, six stories.[62]

- 1897: Y.M.C.A., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a 9-story building projected to cost of $250,000 to build.[63]

- 1898: Daughters of the American Revolution Home, at Fort Pitt Blockhouse, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[64]

- before 1900: St. John's Chapel, Pittsburgh.[65]

- before 1900: Pittsburgh College for Women, remodeling.[65]

- 1900 Wilson College building, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.[65]

- 1904: Economy Public School (renamed Fourth Ward School) at Laughlin and 16th Streets in Ambridge, Pennsylvania (razed 1964).[38][66]

- 1904: Second Ward School, later Ambridge Recreational Center, and Community College of Beaver County Practical Nursing School, on Maplewood Avenue at Eighth Street in Ambridge, Pennsylvania.[38][67] The school was later occupied by Ambridge Recreation, the Community College of Beaver County Practical Nursing School, and the Ambridge High School for Shop and Industrial Arts, before its demolition in 1972.[34]

- 1904: Private residence in Economy, Pennsylvania.[34]

- A group of tract homes for workers in Leetsdale, Pennsylvania.[38]

Published works

- Wagner, Elise Mercur (1924). Economy of Old and Ambridge of Today: Historical Outlines, Embracing the Settlement and Life of Economy of Old, Together with the Vast Development in Recent Years of Ambridge and Surroundings on this Historic Spot. Ambridge, Pennsylvania: Harmony Society. OCLC 6370004.[33]

Notes

- ↑ The earliest primary records for Mercur consistently give her birth in 1864.[1][2][3] After she married her younger husband, records show varying years, i.e. Marriage license gives November 30, 1866,[4] the 1900 census gives November 1869,[5] the 1910 – 1930 censuses show 1871,[6][7][8] and the 1940 census shows 1875.[9]

- ↑ The 1910 census lists an adopted daughter from Hungary, Adele Ribist, age 12,[6] who does not appear in subsequent records.[7]

References

Citations

- ↑ US Census 1870, p. 12.

- ↑ New York Passenger Lists 1879.

- 1 2 3 US Census 1880, p. 75.

- ↑ Allegheny Marriage Records 1898, p. 444.

- ↑ US Census 1900, p. 4A.

- 1 2 US Census 1910, p. 10A.

- 1 2 US Census 1920, p. 3A.

- ↑ US Census 1930, p. 15A.

- ↑ US Census 1940, p. 18B.

- 1 2 Heverly 1886, p. 289.

- 1 2 3 4 The Times 1895, p. 23.

- ↑ Heverly 1886, p. 283-289.

- 1 2 The Atlanta Constitution 1894a, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Banner-Democrat 1896, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allaback 2008, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The New York World 1898, p. 62.

- ↑ McLean 1895, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Fair Hands 1894, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Harvey 2014, p. 226.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 56.

- ↑ Fanton 1896, p. 456.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Post 1896, p. 4.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Post 1897a, p. 21.

- ↑ Muller 1896, p. 15.

- ↑ The Pittsburg Post 1900, p. 18.

- ↑ Municipal Record 1897, p. 135.

- ↑ The American Architect and Building News 1897b, p. xii.

- ↑ The Bradford Star 1898, p. 3.

- 1 2 The Pittsburgh Press 1898, p. 20.

- 1 2 Jordan 1914, p. 1098.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Allaback 2008, p. 138.

- ↑ Architecture and Building 1899, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 The Gazette Times 1924, p. 5:6.

- 1 2 3 PHLF News 2004, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 1947, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Branton 1983, p. 17.

- ↑ New York Passenger Lists 1925, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 The Pittsburgh Press 1947, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation 2007.

- ↑ Kidder 1906, p. 169.

- ↑ The Atlanta Constitution 1894b, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cotton States Exposition Atlanta 1895, p. 106.

- ↑ Appleton 1896, p. 270.

- ↑ Harvey 2014, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Appleton 1896, p. 274.

- ↑ Cotton States Exposition Atlanta 1895, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Post 1897c, p. 3.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Post 1907, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Fahy 2008, pp. A1, A10–A11.

- ↑ Wickersham 1886, p. 490.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Press 1896, p. 8.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Press 1897a, p. 1.

- 1 2 The Pittsburgh Press 1897b, p. 6.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times 1897, p. 14.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Post 1898, p. 14.

- ↑ The Daily Republican 1939, p. 3.

- ↑ Washington & Jefferson College Magazine 2004, p. 31.

- 1 2 Haring-Smith 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ The Brickbuilder 1896, p. 218.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Post 1897b, p. 7.

- ↑ The American Architect and Building News 1897a, p. xvi.

- ↑ Engineering News 1897a, p. 43.

- ↑ Engineering News 1897b, p. 176.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Post 1897d, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Miller 1900, p. 200.

- ↑ Knisley 2014.

- ↑ Knisley 2015.

Bibliography

- Allaback, Sarah (2008). The First American Women Architects. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03321-6.

- Appleton, D. (1896). "Exposition, Cotton-States and International". Appletons' Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1895. Vol. XX New Series (XXXV Whole Series). New York, New York: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 269–277. OCLC 9213131.

- Branton, Harriet (April 23, 1983). "The Forgotten Lady Architect". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. p. 17. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- Cotton States Exposition Atlanta (1895). The official catalogue of the Cotton States and International Exposition: Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A., September 18 to December 31, 1895. Atlanta, Georgia: Claflin and Mellinchamp Publishing.

- Fahy, Joe (December 28, 2008). "Last Reminder of a Lost Era Closes". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. pp. A-1, A-10, A-11. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Fair Hands, Lansby (November 28, 1894). "Women Show That They Know How to Design Exposition Buildings". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. p. 5. Retrieved May 18, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Fanton, Mary Annabele (June 1896). "Architecture as a Profession for Women". Demorest's Family Magazine. New York, New York: W. Jennings Demorest and Co. 32 (8): 454–457. OCLC 692602942. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Haring-Smith, Tori (Fall 2008). "President's Message" (PDF). Washington & Jefferson College Magazine. Washington, Pennsylvania: Washington & Jefferson College. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- Harvey, Bruce G. (2014). World's Fairs in a Southern Accent: Atlanta, Nashville, and Charleston, 1895–1902. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-865-4.

- Heverly, Clement Ferdinand (1886). "Mahlon C. Mercur". History of the Towandas, 1776–1886: including the aborigines, Pennamites and Yankees, Together with Biographical Sketches and Matters of General Importance Connected with the County Seat. Towanda, Pennsylvania: Reporter-Journal Printing Company. pp. 283–289.

- Jones, Sharon Foster (2010). The Atlanta Exposition. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6659-7.

- Jordan, John W (1914). "Wagner". Genealogical and Personal History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania. New York, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 1097–1098. OCLC 6427397.

- Kidder, Frank E. (1906). Building Construction and Superintendence. Vol. 3: Trussed Roofs and Roof Trusses. New York, New York: William T. Comstock. OCLC 13219907.

- Knisley, Nancy Bohinsky (November 23, 2014). "Fourth Ward and the Economy Schools". Ambridge, Pennsylvania: Ambridge Memories. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- Knisley, Nancy Bohinsky (March 4, 2015). "Second Ward School, Ambridge's Second Public School". Ambridge, Pennsylvania: Ambridge Memories. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- McLean, Robert Craik, ed. (February 1895). "Our Illustrations". The Inland Architect and News Record. Chicago, Illinois: Western Association of Architects. 25 (1): 9. OCLC 1639118.

- Miller, Joseph Dana (June 1900). "Women As Architects: The American Woman in Action". The American Magazine. New York, New York: Frank Leslie Publishing House. 50 (2): 199–205. OCLC 1066054349.

- Muller, G. F., ed. (November 14, 1896). "Personals". Pittsburgh Bulletin. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: John W. Black. 34 (2): 15.

- Wickersham, James Pyle (1886). "Washington". A History of Education in Pennsylvania, Private and Public, Elementary and Higher: From the Time the Swedes Settled on the Delaware to the Present Day. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Inquirer Publishing Company. pp. 489–490. OCLC 22954726.

- "1870 United States Census: Towanda Borough, Bradford County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. July 7, 1870. NARA microfilm publication M593, Roll 1312, lines 5–18. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "1880 United States Census: Towanda Borough, Bradford County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. June 26, 1880. NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 1105, lines 8–15. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "1900 United States Census: Harmony Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. June 6, 1900. p. 4A. NARA microfilm publication T623, roll 1374, lines 6–7. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "1910 United States Census: Ambridge Ward 4, Beaver County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 1910. p. 10A. NARA microfilm publication T624, roll 1310, lines 29–31. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "1920 United States Census: Ambridge Ward 4, Beaver County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. January 3, 1920. p. 3A. NARA microfilm publication T625, roll 1531, lines 3–6. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "1930 United States Census: Ambridge Ward 4, Beaver County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. April 14, 1930. p. 15A. NARA microfilm publication T626, roll 1995, lines 43–45. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "1930 United States Census: Economy Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. May 15, 1940. p. 18B. NARA microfilm publication T627, roll 3427, lines 70–72. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "A Successful Woman Architect". The Banner-Democrat. Lake-Providence, Louisiana. October 3, 1896. p. 4. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Building Intelligence: Syracuse, NY". The American Architect and Building News. Boston, Massachusetts: James R. Osgood & Company. LV (1103): xvi. February 13, 1897.

- "Building Intelligence: Washington, PA". The American Architect and Building News. Boston, Massachusetts: James R. Osgood & Company. LVI (1115): xii. May 8, 1897.

- "Buildings:Pittsburgh, PA". Engineering News and American Railway Journal. New York, New York: Engineering News Publishing Company. XXXVII (5): 43. February 4, 1897.

- "Buildings:Pittsburgh, PA". Engineering News and American Railway Journal. New York, New York: Engineering News Publishing Company. XXXVII (19): 176. May 13, 1897.

- "Buildings Saved Only After Hard and Fierce Fight". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. August 1, 1907. pp. 1 – 2. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "C. C. No. 1516". Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Select Council of the City of Pittsburgh. XXX (1): 135. April 5, 1897.

- "Economy Celebration". The Gazette Times. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. May 25, 1924. p. 5:6. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Editorial Notes and Comments". Architecture and Building. New York, New York: W.T. Comstock. 30 (12): 90. March 25, 1899.

- "Introducing Elise Mercur Wagner" (PDF). PHLF News. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (167): 15. September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "Marriage License Dockets, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, vol. 45–46: Wagner/Mercur". Family Search. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Allegheny County Clerk. October 3, 1879. film #878633, certificate #C19332. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Miss Mercur as an Architect". The Times. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. June 23, 1895. p. 23. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Mercur Here". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. December 21, 1894. p. 7. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Moderate Cost Homes". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. May 20, 1900. p. 18. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Elise M. Wagner". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. March 29, 1947. p. 5. Retrieved May 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Elise Mercur Wagner". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. March 29, 1947. p. 10. Retrieved May 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New Children's Building". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. September 8, 1897. p. 3. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New York Passenger and Crew Lists: May 28, 1879 – July 18, 1879". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. June 23, 1879. NARA microfilm publication series M237, Roll 418, lines 7–9. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "New York Passenger and Crew Lists vol. 8453–8454: Aug 28–30 1925". Family Search. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. August 30, 1925. NARA microfilm publication series T715, Roll 3708, lines 4–6. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "New Seminary Building". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. April 20, 1897. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Pittsburgh". The Brickbuilder. Boston, Massachusetts: The Brickbuilding Publishing Company. 5 (11): 218. November 1896. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Announces Historic Building and Landscape Designations". PHLF. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. June 27, 2007. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Pittsburgh's Woman Architect". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. October 26, 1897. p. 14. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Pittsburg's Woman Architect". New York World. New York City. January 9, 1898. p. 62. Retrieved May 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Plans for the new McCullough Building". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. July 30, 1897. p. 7. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Society". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 2, 1898. p. 20. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Some Bright Bits of City Gossip". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. December 20, 1896. p. 4. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The New Hall of Washington Seminary". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. November 13, 1898. p. 14. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "To Build Where the Block House Stands". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. November 28, 1897. p. 2. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Twentieth Century Club". Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. January 31, 1897. p. 21. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "(untitled)". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. December 2, 1894. p. 6. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Vale, Miss Sherrard". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. June 13, 1897. p. 6. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "W&J History Quiz Answer Key" (PDF). Washington & Jefferson College Magazine. Washington, Pennsylvania: Washington & Jefferson College. Winter 2004. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- "Washington Seminary". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. July 5, 1896. p. 8. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Washington Seminary to Continue as Girls' School". The Daily Republican. Monongahela, Pennsylvania. October 18, 1939. p. 3. Retrieved May 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Women's Seminary at Washington, Pennsylvania". The Bradford Star. Towanda, Pennsylvania. April 14, 1898. p. 3. Retrieved October 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

![]() Media related to Elise Mercur Wagner at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elise Mercur Wagner at Wikimedia Commons