Elizabethan furniture is the form which the Renaissance took in England in furniture and general ornament, and in furniture it is as distinctive a form as its French and Italian counterparts.

Gradual emergence

For many years Gothic architecture had been moving toward the low lines of the Tudor style, somewhat impelled by the widespread effects of the Italian trecento. Yet the physical and mental insularity of England made absolute change a very slow process, and it was not entirely achieved during the reign of Elizabeth I. Thus, instead of the exquisite lightness of the pointed and ogee arches, an arch from the time of Henry VIII barely lifts itself above the level of a straight lintel, under square spandrels.

The effects of the Italian Renaissance spread slowly to England, although the Artists of the Tudor court included many immigrants from more advanced milieus. Pietro Torrigiano, Holbein and others were in touch with the latest movements on the Continent.

Long after that Shakespeare finds occasion to speak of

...fashions of proud Italy, whose manners still our tardy apish nation limps after in base imitation.

King Hal himself having had a taste for novelty and splendor that leaned kindly to foreign fashions, and the pageantry of the era of James I, that "wisest fool in Europe," not having wrought immediate effect with the quips and conceits through which eventually the Elizabethan degenerated into the Jacobean.

And if the movement was tardy even then, it was still slower in the previous Tudor era that three-quarters of a century just preceding the precise Elizabethan era. In spite of a few articles of Renaissance furniture procured abroad for the royal family or some of the high nobility, a barbarous mixture of the old and new yet prevailed in England at the period when France enjoyed the accomplished Henry II style, and when Italy reveled in the perfect fantasies of the Italian cinquecento.

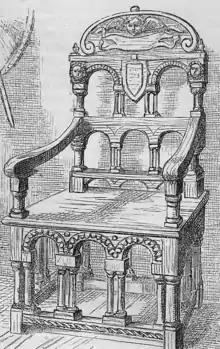

The term Elizabethan has been used distinctively in relation to the Renaissance, rather than exactly in relation to the English styles; for it really began some years before Elizabeth was born and extended over some years after she died, only then receiving its full development. It is not quite possible to fix the exact limits of the different variations of any main style, one shade overlapping and blending with another. Thus there are chairs with the exceedingly high and narrow backs and small square seats which are called Elizabethan, but which were in use with much the same ornament for an indefinite previous period, and there are palaces and country seats built in Elizabeth's last days, but decorated with the additional characteristics more particularly belonging to the Jacobean. In the Louvre and old armory the upper portion is pierced in all the Gothic foliations of the Flamboyant, while the lower portion is decorated with panels carved in all the richest caprices of the cinquecento.[1]

Classic influence

Attempts at classicism are everywhere in the Elizabethan. Once in a while in a mantelpiece the attempt is almost a success, and the result an exceedingly stately and beautiful object with channeled columns, architrave, and frieze. But poorly executed work has a few pillars and pilasters with misunderstood details, a strap often clasped and buckled about them, some clumsy scrolls and rosettes, with masks and busts of the ancients, scattered ill-drawn human figures, and here and there huge terms, heads rising from flat vases, or pedestals narrowing at the base.

Grecian columns of singular disproportion form the main structure of bedsteads, tables, and cabinets. These columns are noted for their clumsy thickness, and in one of the first misapprehensions of the classic that mark the style, they rise from huge spherical clusters of foliage, usually the acanthus. At about half their length, these columns are frequently broken by another huge spherical cluster; on this sometimes half the foliage growing downward, half growing upward, and divided in the middle by a careful strap and buckle; occasionally the upper half of this globe is absent. The lower part of the columns is often covered with arabesques, and the upper half merely fluted, or else covered with a fine imbricate carving. In some of the tables, instead of columns, a sort of caryatid — female half-figure, neither exactly sphinx nor monster, dressed out in straps and ending in rude scrolls — formed the support at each of the four corners.

The tables thus upheld were mighty constructions, sometimes they can be pulled apart in an extension, but oftener bound by firm crossbars and almost immovable through their weight. In the cabinets the lower part was usually a closed cupboard, paneled and ornamented, with terms between the different divisions, the figure issuing from the vase being now a head only, and now two-thirds of the whole; the top projected, and was upheld by the big columns; and all the surfaces were enriched with sculptures after the approved fashion.

Of the bedsteads with heavy canopies and cornices, the Great Bed of Ware follows the styles, although it is a caricature in size. Sir Toby Belch speaks of this piece of furniture when he advises Sir Andrew Aguecheek: "And as many lies as will lie in thy sheet of paper, although the sheet were big enough for the Bed of Ware in England, set 'em down; go about it." Still, it is to be remembered that its twelve-foot square size was not at all unusual, and was matched by other beds on the Continent.[1]

Although its curious translation of classic shapes is significant, the strap and buckle predominate over everything else.[1]

Strap and buckle

Strapwork, together with shieldwork, was very prominent in the Henry II style. It was a method of ornament particularly applicable to jewelry and work in gold. Cellini used it entirely. "I therefore made four small figures of boys," says he, "with four little grotesques, which completed the ring; and I added to it a few fruits and ligatures in enamel, so that the jewel and the ring appeared admirably suited to each other." Both in the French and the Italian work the method was mingled with better classic detail, and with finer natural imitation, but hardly in the Saracenic itself was the tracery so prominent as in the Elizabethan. If the type was meager, its play of line was infinite: curve led to curve, intricacy to intricacy, and over all ornamented surfaces, the scrolls that supported other forms — panels or scutcheons or masks — the figures, the faceted jewel forms, opened into successions and sequences of interlacing and escaping straps and ribbons, and transformed into the representation of all the gay buckling and harnessing of chivalry.

These ribbons and straps and buckles were always flat in surface, however curved in shape and situation, and they rose from their background at right angles as actual straps would if laid on flatly, not using contrasts of light and shade, but seeking only the effect of line chasing line. When the use of the cartouche became more general, one form of light and shade came to the assistance of this sort of ornament, for the supports of the shield were frequently pierced with countless openings, crescent-shaped, lozenged, circular, rectangular, apparently in a mere haphazard openwork, but revealed in an overall view as repeating the straps and ribbons again with the contours of their perforation. While this pierced shieldwork, with its innumerable flat and curved planes, came afterward to assume more importance in the Jacobean, there was nothing of the Elizabethan that was not ornamented with the strapwork in some form or other.

The vast screens between the sides of rooms or walls themselves were filled with flourishes of this carven tracery, as seen in Crewe Hall. Even of the ceilings conformed to the carved style. There are few grander effects in interior decoration than the intersecting curves and angles of a lofty old Elizabethan ceiling. Of course, in the use of the strap and shield, heraldry and its escutcheons and crests entered largely into the ornament of the Elizabethan. The ensigns armorial, set in all shapes and surrounded by all the curious mantling to be devised, appeared everywhere in conjunction with the family motto and with the intertwined initials of husband and wife, over gateways, over doorways, on dead-wall, over the fireplace; and stairways were decorated with carved monsters sitting on the baluster-tops and holding before them the family arms, frequently looking as if they had just escaped from one of the quarterings. Even such a room sometimes had stylistic mixtures such as wainscots which were set in the little square panels or in the parchment panels of the preceding reigns, or in the round-arched panels peculiar to the Elizabethan itself — miniature and open representations of which are to be seen on the back of the chair made from the wood of Sir Francis Drake's ship. [1]

Absorbing of Gothic

Nevertheless, in the Elizabethan the Gothic is never quite forgotten. Its vertical lines are always breaking through the horizontal of the invading classic; its reverend monsters look with special unkindness on the fantasticism of the new monsters that Cellini described as the promiscuous breed of animals and flowers; its ornaments insist upon their right before the Grecian; in architecture its gables still rise, although with a skyline gnawed out by the scrolls as worms gnaw out the sides of a leaf; and in furniture its cove surmounts the tops of those cabinets whose fronts are the facades of temples. The steadfast English mind clung to the old order of things, and relinquished with reluctance the last relics of a style that had been for centuries a part of its life. If it must have the egg and dart, it would keep the Tudor flower too. Thus all the Renaissance that came into England, after the bloody Wars of the Roses made it possible to think of art and luxury, paid toll to the Gothic on the way, and the result was a singular miscellany, for its Gothic had now forgotten, and its Renaissance had never known why it had existed. It is rather the talent with which the medley of material was handled, the broad masses, yet curious elaboration, and the scale of magnificence, that give the style its charm rather than anything in its original and bastard composition.[1]

Influence of the Low Countries

The Renaissance of the Elizabethan came into England by way of the Low Countries. The importation of furniture into England from Flanders and Holland was so significant that a hundred years earlier a law was enacted forbidding the practice — nevertheless carved woodwork was one of the important articles of commerce with the Low Countries, and the country homes of England of this period were filled with articles of Dutch and Flemish workmanship.

Historical influences include:

- Residence in England of numbers of exiles fleeing from Spanish oppression and events such as Sack of Antwerp.

- The occupation of the Netherlands by English forces during the Dutch Revolt.

- English sympathy with the struggles may have affected the fashion.

Whether from any of these causes or from purely commercial ones, what became part of the Elizabethan furniture style was the top-heavy and overloaded Dutch cabinet and the table with big columnar legs capable of upholding mighty serving dishes, and both covered with Flemish ornament. Many forgeries in the style were made in Holland long afterward due to their high value.

It is this importation and custom that accounts for something of the character of the Elizabethan articles; for the Flemings, although fond of magnificence, and accustomed to all the splendor of the Burgundian court, never became absolute masters of the fully developed Italian style. Nor was the Fleming so thoroughly the master of his materials that his execution quite answered his ideas. Both German and Spanish workmanship came much nearer to the complete spirit of the Renaissance, the latter leaving little to be desired. The Flemish is, however, generally held to be the most dramatic carving of the North. Although the French handled the human figure lightly and fancifully their drawing was apt to be incorrect, such as in giving too much weight and size to the head. Yet after some years the Flemish work became less dignified and desirable. It was lumbered with turned work sawed in half and glued on, with panels overlaying and intersecting each other at odd angles, and with cumbrous pendants under the corners, all of which work was injurious, and much of which was ugly. In the later period of the Elizabethan, the Italians themselves may have supplied artists and workmen for the furniture, but they must have worked hampered by the tastes and prejudices existing around them. A certain rudeness of carving prevails throughout the earlier part of the style, and is considered to give breadth of effect. The old carvers hid none of the means by which they gained their ends, and left even the tool marks in full sight.[1]

Scallop shell

In that portion of the Elizabethan which is often considered as the Jacobean, although it was but the completer development of the former, the globular excrescences of the columns elongated themselves into equally vast and far uglier acorn-shaped supports. A good deal of inlaid work was then used, and the carving did its best to reach and render the ideas of the cinquecento. It is, indeed, styled the cinquecento period of English art, every surface being rough with arabesques of griffins, vases, rosettas, dolphins, scrolls, foliages, Cupids, and mermaids with double tails curling round them on either side. Meantime the cartouche and its straps — ligatures they were called in Italy, cuirs in France and Flanders, were still often used.

Scallop shells received a particular share of favor, having been recently brought home from foreign seas, and was immediately seized by the designers in need of other shapes. The Flemings made seats that enclosed the sitter in the valves of this scallop, carved just rudely enough to excuse their eccentricity. The design of the scallop shell back for chairs is associated with the designer Francis Cleyn who worked in England from the 1620s.[2] Settees were made at this time whose backs consisted of several just such immense scallops as those of these Holland House Gilt Chamber chairs;[3] and the same idea of decoration peeps out in fan-like frills at every spare corner of the Neo-Jacobean revival of the style. These shell forms of furniture might befit an oceanside home, but they must have been singularly out of place on dry land and among the huge and heavy articles that surrounded them in the Jacobean mansions.

There was something, on the whole, in the early Elizabethan replete with dignity, a massy magnificence that agreed with that of the era and the monarch, that went well, too, with the mighty farthingales and ruffs of the ladies, the trunk-hose and puffed and banded doublets of the gallants, while the people who used it — Shakespeare, Walter Raleigh, Ben Jonson, Francis Bacon — still have a peculiar interest. Well as it suited doughy old Queen Bess herself, the forms which it took under her successor, with their assumption of foreign conceits and their display of profuse gilding, accorded no less characteristically with the arrogant, pedantic, and petty James. All of this furniture, however, is exceedingly attractive, and there are few who would not rejoice over any article of it which is not too unwieldy for modern quarters. A typical sideboard and dresser offer a medley of design, with not too well drawn fawns and satyrs, fruits and flowers, Cupids, birds, scrolls, shields and straps, cornucopias, mermaids, monsters and foliages. They belong to the beginning of the later period. It was no light matter to clear the floor for the dance of the Capulets when the servant cried "Away with the joint-stools, remove the court-cupboard, look to the plate!".[1]

Porcelain and mirrors

By the close of the Jacobean era, the style held its own with slight variation and innovation, for some reigns. The execution of the carving was coarse and careless during the time of the first Stuarts, but afterward rose to be classed with the finest known; inlaid work, also, was more freely used and attained much excellence. There was increasing prevalent luxury in every thing. Fine pottery, for instance, became more frequent; for although glass had been made in London under Elizabeth's patronage, "porselyn" was rare, and even earthenware was not then very general, gold and silver plate making the vessels of the rich, and pewter mugs and platters and wooden trenchers being still those of the poor, while mention is made of "five dishes of earth painted, such as are brought from Venice," which were presented to the queen as something unusual; and it was thought a gift not unworthy of royalty when Lord Burleigh offered her a "porringer of white porselyn garnished with gold." The first use of the famous Dutch tiles is thought to belong to the reign of Charles I.

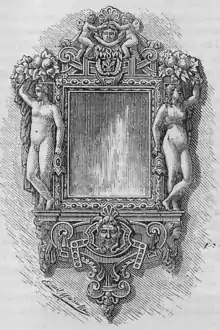

Mirrors, which were very rare in Elizabeth's time, became more common in that of the Charleses, the Duke of Buckingham, during the reign of the second Charles, bringing a colony of Venetian glassmakers to Lambeth. One Elizabethan mirror is some three and a half by four and a half feet in size — five feet was the largest made till the latter part of the eighteenth century — the frame is carved in oak and partially gilt, and the glass is set flatly. In one mirror of the time of Charles II the glass is beveled, and in the glasses of the Merry Monarch's predecessor the frames were so made as to throw the glass forward and give it projection. Quicksilvered glass itself, unset, became a novelty, so that sometimes whole rooms, and even the ceilings, were lined with it. The mirrors made by the duke's colony were of superior excellence; they had an inch-wide bevel all along their outer extremity, whether they were rectangular or curved. "This," says Mr. Pollen, "gives preciousness and prismatic light to the whole glass. It is of great difficulty in execution, the plate being held by the workman over his head, and the edge cut by grinding. The feats of skill in this kind, in the form of interrupted curves and short lines and angles, are rarely accomplished by modern workmen, and the angle of the bevel itself is generally too acute, whereby the prismatic light produced by this portion of the mirror is in violent and too showy contrast to the remainder."

Wall hangings had been long in use — the leather, the damask, velvent, and arras or tapestry. The Flemish tapestries, from the time of their first manufacture, were in great favor. Elizabeth had a set wrought signalizing the dispersion and destruction of the Spanish Armada. So fine had they become that they were often preferred to other decoration, and in the Stuart time were stretched across the noble old carved panelwork itself. "Here I saw the new fabric of French tapestry," wrote Evelyn, in the last years of Charles II, concerning the Gobelins tapestry, established under the royal patronage in France: "for design, tenderness of work, and incomparable imitation of the best paintings, beyond any thing I had ever beheld. Some pieces had Versailles, St. Germains, and other palaces of the French king, with huntings, figures, and landscapes, exotic fowls, and all to the life rarely done." Yet works in tapestry had been, long before this, under royal protection in England also, the Raphael cartoons having been purchased by Charles I for the use of the Mortlake Tapestry Works, which, however, did not outlast that sovereign more than half a century; and the employment of draperies had become so profuse that they now largely took the place of the heavy paneled wooden tops which had so long encumbered the bedsteads.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Elizabethan and later English furniture". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 56 (331): 18–33. December 1877. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ↑ Megan Shaw, 'The Duchess of Buckingham's Furniture at York House', Furniture History, 58 (2022), p. 22.

- ↑ Nicholas Cooper, 'Holland House', Architectural History, vol. 63 (2020), p. 60.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Harper's Magazine from 1877–78

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Harper's Magazine from 1877–78