The Emilie[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] was a sidewheel steamer, designed, built and owned by the famed riverboat captain Joseph LaBarge, and used for trade and transporting people and supplies to various points along the Missouri River in the mid nineteenth century. The Emilie was built in Saint Louis in 1859, was 225 feet in length with a 32 foot beam and had a draft of six feet.[3][4] Larger than the average riverboat at the time, she could carry 500 tons of cargo.[lower-alpha 3] During her extended service on the Missouri River she also fell into the hands of both Union and Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. As a result of her numerous exploits, Emilie was among the most famous boats on the river and was widely considered a first rate and an exceptionally beautiful riverboat.[6][7][8] After some nine years of service the Emilie was caught in and destroyed by a tornado on June 4, 1868.[9]

History

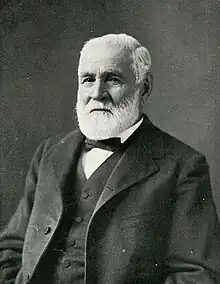

Having worked many years for the American Fur Company[lower-alpha 4] as a riverboat captain and pilot, LaBarge went into business for himself and proceeded to design and build his own riverboat. Pierre Chouteau Jr. of the fur company having learned of LaBarge's prospects sent word to him and offered any assistance he might need in completing the vessel that would soon be widely known as Emilie. The American Fur Company still valued Captain LaBarge's ability and familiarity of the Missouri River and would gladly have taken him, and his exceptional riverboat, back into their employ, but LaBarge declined the offer. Prior to its completion LaBarge contracted with the Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroad, which had just reached Saint Joseph on the Missouri River. From Saint Joseph it ran to points up and down the river in connection with various roads, making trips as far north as Fort Randall.[6][2] Upon completion of the vessel, LaBarge named her the Emilie, after one of his daughters. Emilie's maiden voyage occurred on LaBarge's forty-fourth birthday, October 1, 1859.[6][11]

Emilie's most famous passenger was Abraham Lincoln when he visited points along the Missouri River in August 1859, stopping at council Bluffs to examine some real estate.[6][5] In late autumn, river ice prevented the Emilie from leaving Atchison, Kansas, forcing the vessel to remain docked nearby for the duration of the following winter. When spring arrived the citizens of Atchison requested that the Emilie be used as an ice-breaker to open a passage between Atchison and Saint Joseph some twenty miles to the north on the Missouri side of the river. LaBarge carefully maneuvered the bow of boat up on to the ice until it broke under the weight of the huge vessel, and did this repeatedly until he reached Saint Joseph. The next year ice once again caught LaBarge and the Emilie near Liberty, Missouri. While detained there he received news that his former passenger, Abraham Lincoln, had been elected president.[6][5]

Civil War involvements

In June, 1861 the Emilie, still under the command of its owner, Captain Joseph LaBarge, was cruising down the Missouri River not far from Boonville, just after the Confederates had retreated from that town during the Battle of Boonville. Not aware of the situation, Captain LaBarge received warning shots over head from Confederate forces still present in the surrounding area, and was forced to round to and stop. The Confederate General John S. Marmaduke and a company of troops boarded the Emilie with orders for LaBarge to take the aleing General Price up river to Lexington for treatment. LaBarge explained that he could not comply because he was "in the service of the government", delivering freight. At that point, though LaBarge happened to know Marmaduke "well", he was placed under arrest as a matter of routine and his boat was commandeered. LaBarge protested again, that he would have to pay his crew for their extra time, and for additional fuel for the added distance involved, where Marmaduke agreed to compensate him for his time and trouble. General Price was brought aboard and Marmaduke left the boat in the hands of his officers, and the Emilie set off for Lexington. After dropping off Price, LaBarge was allowed to depart with the Emilie, but received no compensation, as promised by Marmaduke, from the Confederate officer left in charge, who figured LaBarge was well off enough to leave with his boat intact, where the Emilie headed back to Boonville. Upon approaching that town, now occupied by Union forces, the Emilie was fired upon again and forced to stop, where LaBarge was brought to and questioned by Union General Nathaniel Lyon.[lower-alpha 5] After establishing his well known identity and purpose on the river, LaBarge was permitted to depart with the Emilie, but with all her freight having been confiscated by Union forces.[13][14]

On October 16, 1862 the Emilie had stopped at Portland to drop off a couple of passengers. While docked an outfit of Confederate soldiers rushed out from behind a woodpile and came aboard the Emilie. Captain LaBarge was forced to unload his cargo and ferry 175 Confederate cavalry men and their horses across the river. No sooner had they departed when a company of Union cavalry arrived on the scene, but not in time to stop the operation. These were the only two occasions that Captain LaBarge experienced trouble on the river because of the war.[15][14]

Race with Spread Eagle

In the spring of 1862, Joseph LaBarge, his brother, John, and several other partners formed the firm of LaBarge, Harkness & Co. based in Saint Louis, for purposes of trading on the upper Missouri River. The company's two principle riverboats were the Emilie and the Shreveport. That spring the Emilie was about to make the annual run north, bringing people and supplies to Fort Benton in Montana, the farthest navigable point on the river,[16] 2300 miles from Saint Louis, by way of river.[lower-alpha 6] The fort served as a trading post and supply center for trappers and mining operations in the region. The American Fur Company was also involved is its annual journey to the fort with its riverboat, the Spread Eagle. The Emilie was commanded by Captain Joseph LaBarge, and the Spread Eagle, by Captain William Bailey. The Emilie, the faster of the two vessels, had departed from Saint Louis four days after the Spread Eagle but eventually caught up to her at Fort Berthold. The venture at this point turned into a heated race between the rival companies and crews when the Emilie attempted to pass the Spread Eagle. Realizing that the Spread Eagle was about to fall behind, Captain Bailey ordered the pilot to ram the starboard bow of the Emilie in an attempt disable her, or at least impede her performance.[18] The collision occurred dangerously close to the boilers of the Emilie. In the calamity a gunfight nearly broke out between the two crews, but was averted when the two boats broke free from the other. The attempt to disable Emilie failed, and only resulted in minor damage to the vessel. Emilie, regardless, managed to reach Fort Benton four days before the arrival of the Spread Eagle.[19][20] As a result of the race, the Emilie was the first sidewwheel steamboat to reach Fort Benton.[9]

Late in the winter of 1862–1863 Captain LaBarge sold the Emilie for $25,000 to the Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroad.[21]

See also

- Ontario (steamboat), the first steam driven sidewheeler steamboat to see active service on the Great Lakes, at Lake Ontario.

- Walk-in-the-water (steamboat) — first steamboat to run on the Great Lakes at Lake Erie, Lake Huron and Lake Michigan

- American Fur Company – Major owners and employers of steamboats on the Missouri River

- North American fur trade

Notes

- ↑ Some accounts spell it as Emily[1]

- ↑ Not to be confused with the Emilie La Barge, also built by Joseph LaBarge, in 1870 [2]

- ↑ The average cargo capacity during this period was 200–300 tons.[5]

- ↑ Labarge first signed on with the American Fur Company at age 17, as a clerk.[10]

- ↑ Nathaniel Lyon was the first general to die in the Civil War.[12]

- ↑ Established in 1846 by the American Fur Company, Fort Benton was the first permanent settlement near the Great Falls.[17]

References

- ↑ Sunder, 1965, pp.234, 286

- 1 2 Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1875, Vol IX, p. 301

- ↑ Casler, 1999, pp. 32, 40

- ↑ Riverboat Dave's

- 1 2 3 Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 459

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chittenden, 1903, Vol I, pp. 240–241

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol II, pp. 255–259

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, pp. 458–459

- 1 2 Casler, 1999, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol I, p. 23

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 458

- ↑ Eiecher, 2001, Civil War High Commands, p. 357

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol II, pp. 255–258

- 1 2 Harper, Historical Society of Missouri, 2019, essay

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol II, pp. 258–259

- ↑ O'Neil, 1975, p. 14

- ↑ Cutright & Brodhead, 2001, Elliott Coues: Naturalist and Frontier Historian, p. 175

- ↑ Eriksmoen, Bismarck Tribune, Sept. 2, 2012

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Volume II, pp. 287–290

- ↑ O'Neil, 1975, p. 30

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol II, p. 298

Sources

- Adams, Franklin George; Martin, George Washington; Connelley, William Elsey, eds. (1875). Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Vol IX. Topeka, State Printing Office, 1905-1906.

- Bowdern, T. S. (July 1968). "Joseph LaBarge Steamboat Captain". Missouri Historical Review. The State Historical Society of Missour. 62 (4): 449–470. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Casler, Michael M. (1999). Steamboats of the Fort Union fur trade: An illustrated listing of steamboats on the Upper Missouri River, 1831-1867. Fort Union Association. ISBN 978-0-9672-2511-1.

- Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1903). History of early steamboat navigation on the Missouri River : life and adventures of Joseph La Barge, Volume I . New York : Francis P. Harper.

- —— (1903). History of early steamboat navigation on the Missouri River : life and adventures of Joseph La Barge, Volume II . New York : Francis P. Harper.

- Eriksmoen, Curt (2012). "Riverboat captain 'carried' bullet that killed Hickok". Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- O'Neil, Paul (1975). The Riverman. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-1496-3. - (Also in PDF format)

- Sunder, John E. (1993) [1965]. The Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri, 1840-1865. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2566-4.

- Harper, Kimberly. "Joseph Marie LaBarge". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- "Joseph LaBarge". riverboatdave's.org. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

Further reading

- Athearn, Robert G. (1972). Forts of the Upper Missouri. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5762-7.

- Boller, Henry A (1868). Among the Indians. Philadelphia : T. Ellwood Zell.